In the summer and autumn of 1969 Anselm Kiefer, then aged twenty-four and a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe, undertook a series of actions that collectively he termed Occupations.1 Wearing a variety of often outlandish outfits – from hippie gowns to paramilitary uniforms – he photographed himself in different locations in Europe performing the taboo Sieg Heil Nazi salute, a provocative gesture and a punishable crime in Germany since 1945. The resulting photographs were given the collective title Heroic Symbols, which was derived from a 1943 article in the official Nazi arts magazine Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich (in English Art in the German Reich) that consisted of illustrations of ‘heroic symbols’ – paintings, sculptures and monuments – from German culture.2 The group of photographs, six of which are held in the ARTIST ROOMS collection owned by Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, document the scale of Kiefer’s project, not only in terms of the sheer number of salutes he made, but by revealing how far he travelled. Beginning in Germany, Kiefer rehearsed the gesture in his private home-studio in Karlsruhe and outdoors in the nearby countryside, as well as on the east bank of the Rhine, before journeying to various public sites in Europe, often staging the action at locations where there were some traces of an imperial past. In France he saluted in front of the statue of the French king Louis XIV in Montpellier, and facing the Mediterranean Sea in nearby Sète, as well as at the Roman necropolis in Alyscamps, Arles. In Switzerland he saluted in Bellinzona, and in Italy under the colonnades of the Colosseum and St Peter’s in Rome, among the ruins of the Roman forum at Paestum, in Caprarola, and in Pompeii, and even by the crater of Vesuvius. On each occasion numerous photographs were taken, some with only slight shifts in viewpoint. In 1975 eighteen of the many Heroic Symbols photographs were selected by Kiefer for publication in a controversial photo-essay entitled ‘Occupations’ in the German conceptual art magazine Interfunktionen.3

The shock factor of these photographs when they were disseminated in the public sphere in Intefunktionen would have been the presentation of the Nazi salute, which, along with publicly displaying Nazi symbols, had been an offence in Germany since the end of the Second World War. After 1945, Germany went through an intense process of denazification, an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian culture and society, and particularly the press, economy, judiciary and politics, of any remnants of National Socialist ideology, a process that also encompassed the Nuremberg Trials held between November 1945 and October 1946. Swastika symbols at the Nazi party rally grounds in Nuremberg and all over Germany were also demolished with explosives, as a highly visible part of this denazification initiative. Denazification officially came to an end in 1948, but the impulse to purge society of National Socialism continued in various other ways, notably through the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials (1963–5), when photographic evidence was used to condemn Nazi war criminals, photographs that were also circulated in the mass media, and the publication in 1965 of Albert Norden’s Braunbuch. Kriegs- und Naziverbrecher in der Bundesrepublik: Staat – Wirtschaft – Verwaltung – Armee – Justiz – Wissenschaft (in English Brown Book: War and Nazi Criminals in West Germany: State, Economy, Administration, Army, Justice, Science), which, as the title indicates, listed approximately 1,800 former Nazis who had evaded denazification and returned to positions of influence, particularly during the Konrad Adenauer administration from 1949 to 1963. Kiefer’s representations of the Sieg Heil salute, especially when staged in locations that connoted imperial authority, could well have reminded the public of such infiltration, as well as the not-so-distant past when Germans en masse were swept up by Hitler’s impassioned, vision-laden oratory, and saluted in the presence of their leader. Because Kiefer occupied the role of the saluting Nazi himself in these photographs, his work had greater potential to provoke than Gerhard Richter’s earlier blurred photo-painting Uncle Rudi (1965), which depicted the artist’s maternal uncle smiling and posing in his new Wehrmacht uniform not long before he was killed in action in 1944.

The gradual comeback of former National Socialists into public sectors was, unsurprisingly, highly controversial, and from the 1960s a powerful political movement of German students protested against it, sustained by the writings of Frankfurt School Marxist intellectuals such as Herbert Marcuse and Theodor Adorno (a thinker much admired by Kiefer),4 and driven by their distrust and anger towards the older generation, especially those who had remained quiet about the National Socialist past. This anger culminated in the dramatic events of the so-called ‘German Autumn’ (German: Deutscher Herbst), when on 18 October 1977, the extreme left terrorist group the Red Army Faction murdered their hostage Hanns-Martin Schleyer, President of the Confederation of German Employers’ Associations. They did so after their release demands for imprisoned fellow members of the Baader-Meinhof Group failed, and on learning that three of them had been found dead in prison, the result of a suicide pact. But their violent act of murdering Schleyer can also be interpreted as a symbolic act of patricide, since Schleyer was part of a network of former Nazis who still had great economic power and political influence in West Germany.

After the war, German artists in the Federal Republic rarely visually acknowledged the violence of National Socialism, much less the Holocaust, or indeed the presence of some former Nazis in German society, and abstraction was heavily promoted, particularly through the Kassel Documenta exhibitions, as an international visual language. There was hope from those responsible for cultural policy, such as Werner Haftmann (1912–1999), an influential art historian, critic, curator and Documenta committee member, that through a shared language of abstraction, post-war artistic life in West Germany could help overcome any dark residual images and memories of National Socialism, as well as distinguishing itself from the Socialist Realist artistic doctrine of the German Democratic Republic. Exponents of abstraction sought effectively to empty out all troublesome figurative content, and this stressing of autonomous rather than committed art marked an ideological difference from the aesthetics of totalitarian regimes; democratic ‘autonomy’ was thereby considered part of a West German ‘re-education’ for integration into Europe. While abstract painting was not the only artistic impulse of post-war West Germany, it was a dominant one. For many, both left-wing students and cultural policy makers, the transgressive shock and resonance of Kiefer’s Heroic Symbols project would have been that he was bringing back the image world of fascism, albeit in a somewhat altered form, and irrespective of the fact that he was, in so many ways, deconstructing that troubled past. As will be discussed, the nuances of what he was trying to achieve were lost on the liberal readership of Interfunktionen who simply could not get past the provocation of his representing the forbidden salute, a gesture that caused a reflex reaction of disapproval, just as it had once caused a reflex of compliance.

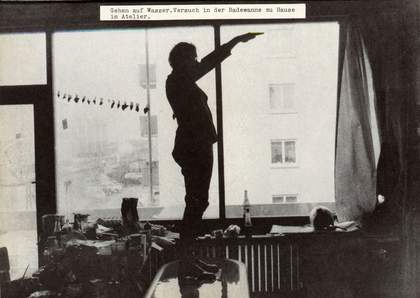

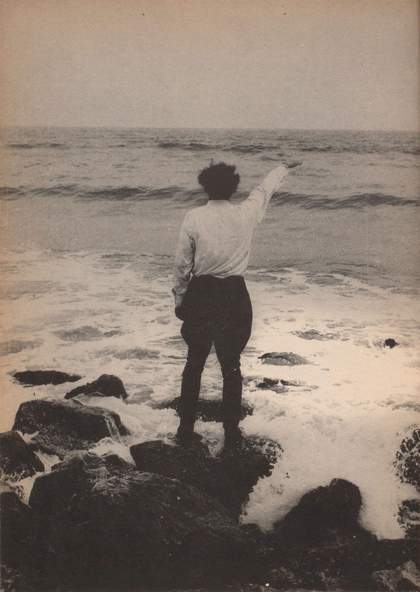

Fig.1 Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Photograph, black and white, on paper

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

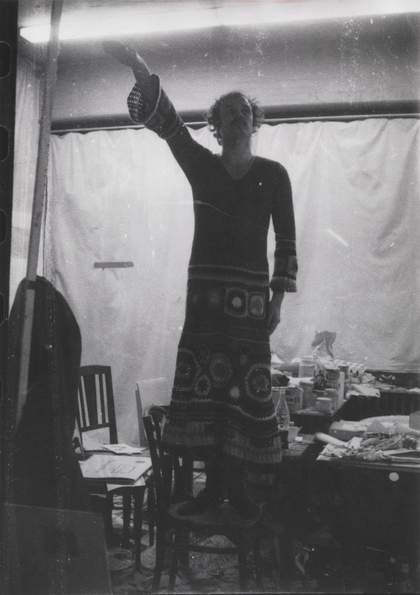

Fig.2

Anselm Kiefer

Occupations (Besetzungen) 1969

Collage, black and white photograph

Published in the photo-essay ‘Occupations’, Interfunktionen, no.12, 1975

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer

There is a feeling of voyeuristic intimacy as well as a sense of child’s play about the photographs Kiefer took in his studio in Karlsruhe where he first rehearsed his provocative ‘action’. In addition to dressing up he often used models, toys and other props in his studio as a means of imaginatively staging war-game scenarios, a form of peculiar playacting that both exposes and deflates the pomposity of totalitarianism. In one of the studio photographs Kiefer, clad in the heavy military overcoat he found in his father’s attic, appears to be standing casually in riding boots on the surface of glassy still water that fills a bathtub (Tate AR01174; fig.1). On closer inspection it is possible to see that he is actually standing on a submerged stool that has been placed in the centre of the bath. In Kiefer’s Heroic Symbols artist book, one of several created in 1969 in which some of the many Heroic Symbols photographs were included, several of the studio photographs are captioned ‘Gehen auf Wasser. Versuch in der Badewanne’ (‘Walking on Water. Attempt in the Bathtub’), which, aside from the obvious biblical reference to Christ’s miraculous act across the Sea of Galilee, refers to a joke in popular currency during the National Socialist era that Hitler walked on water because he could not swim. In this photograph, the scene is made particularly absurd – mundane rather than miraculous – by the kitchen utensils on a two-ring hob, the motorcycle helmet by the window, and the chaotic sprawl of bottles, jars and pots of paint, the general artistic detritus of his live-work space. Two related ‘Walking on Water’ photographs were also used in the ‘Besetzungen’ (Occupations) photo-essay of 1975 (fig.2), but these have a slightly different effect in that Kiefer, again wearing some kind of pseudo-military garb, is silhouetted by natural light against his curtainless windows so that the apartment blocks over the street from his home-studio are clearly visible.

Fig.3

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Photograph, black and white, on paper

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

In another studio photograph Kiefer stands on a chair and gives the Sieg Heil salute under harsh fluorescent strip lighting (Tate AR01162; fig.3). Beyond capturing a taboo moment, the sinister aspect to this image is heightened by poor illumination and the makeshift screen or curtain behind the artist that blocks any natural light from entering the room. If it were not for the messy gathering of artistic materials and a two-thirds empty bottle of Coca-Cola located on the table behind him, the claustrophobic space might have the appearance of some kind of interrogation cell. However, such sinister associations are dispelled by the absurdity of Kiefer looking like an unkempt hippie peace activist, wearing a loose-fitting patterned crocheted dress while presenting his salute, a look that manages to defuse the assumed authoritarian compliance of the gesture.

Leaving aside the cross-dressing images taken in his Karlsruhe studio, even in his outdoor photographs (for instance in Bellinzona where he dons the military coat he also wore in some of the studio photographs) there is never a point when Kiefer truly resembles a military man – the archetypal Nazi. At no juncture does he wear full Nazi uniform, but rather dons a dark green coat, shirt, boots and jodhpurs, the latter looking somewhat baggy. Again, he appears unkempt with his unruly thinning hair and he wears his outfit with the air of a Sixties dropout student rather than a member of the Gestapo. In other photographs, especially those that show him giving the Nazi salute on the Mars-like terrain of a volcanic crater on Mount Vesuvius, he dispenses with the pseudo-military outfit, and wears a suit, sandals and Easy Rider-style sunglasses (Tate AR01172; fig.4). By chance the sun catches a fold in the crotch of his trousers making it appear as if he has a contained erection. This fold mirrors his saluting movement; a libidinal ‘attachment’ to the gesture. On the one hand, it could be argued that Kiefer’s choice of contemporary attire might be a comment on the persistence of Nazism in post-war civilian society, a reference to the presence of some former National Socialists in German places of work in spite of denazification; on the other, as alluded to above, his detachment from the typical physical appearance and stiff posture of a Nazi seems to be a critique of nationalist militarism, a form of paternal disidentification, and a gesture more in line with the goals of the German Student Movement, the leftist ’68-ers.

Fig.4

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

The art historian Lisa Saltzman has argued that photographs taken either in ‘Kiefer’s apartment or in Switzerland, France or Italy underscore the point that their staging could not take place within the public sphere in Germany’.5 This observation may be true of those included in the ‘Occupations’ photo-essay of 1975, which excluded outdoor German locations, but some of the photographs were taken in a remote part of the countryside outside Karlsruhe, and some were taken by the banks of the Rhine. However, Kiefer has stressed that those photographs taken in such places in Germany were part of his ‘preparatory’ work for the series of actions that were staged in non-German locations.6

A certain mystery surrounds Heroic Symbols in terms of the authorship of the photographs taken in various European locations. This is not conclusively addressed in the literature on Kiefer. Some art historians have proposed that ‘he took a series of photographs’ (Mark Rosenthal), while others have suggested that he ‘had himself photographed’ (Benjamin Buchloh).7 Technically, it is clear that many of the photographs in Kiefer’s studio could have been taken on a timer. However, many of the photographs shot ‘on location’ were taken from unusual perspectives, often in difficult terrain or in civic spaces, and some from a relatively great distance. These factors would have made the use of a camera timer, which in the 1960s usually had short delays, highly problematic, especially given the possibility of public or police intervention.

In Kiefer’s one-page autobiography created in 1976, the ten entries for 1969 include one reference to ‘Julia’ after a reference to ‘Adolf Hitler’ and seven entries after ‘Motorcycle’.8 1969 is the year that Kiefer met Julia, who later became his first wife, and who featured as a ‘character’ in a number of Kiefer’s artworks in the 1970s. This may suggest that Julia accompanied Kiefer around Europe in 1969, perhaps on a motorbike. However, in 2013 Kiefer claimed that the photographs in Montpellier were carefully coordinated by him but taken by a male friend. Given the taboo nature of the Nazi gesture the two men could not afford to spend too much time documenting the action, and in Montpellier he was approached by older men who wanted him to explain his behaviour.9

The mystery surrounding the taking of the photographs leads to the question as to whether or not these photographs can be considered ‘self-portraits’. For various reasons that will be discussed during the course of this essay it would seem that ‘self-portraiture’ is perhaps not the most apt defining category with respect to these early photographs, and not simply because some of them cannot physically have been taken by Kiefer. Revealingly, the artist has suggested that he does not view such works as self-portraits in any conventional sense, but as investigations of various roles in which ‘I used myself as the material. Like color’.10

Imperial locations and ruined empires

Challenging a point sometimes made about Kiefer’s Occupations performance and Heroic Symbols photographs, Kiefer scholar Andrea Lauterwein has suggested that the places that Kiefer chose to ‘occupy’ during the summer and autumn of 1969 were ‘never the objects of military conquest but were in fact tourist attractions in southern Europe’.11 To provide an alternative interpretation of the work, she then suggests that Kiefer’s journey brings to mind the Third Reich’s leisure organisation ‘Kraft durch Freude’ (in English ‘Strength through Joy’), which after 1937 arranged affordable holidays to Italy and Spain where Germans were ‘encouraged to note the contrast between the countries of the South and those of the North, thus reinforcing their passionate devotion to German industry and hygiene’.12 While these observations are persuasive, it should be noted that Kiefer did not always choose obvious ‘tourist sites’ but rather sites where there were traces of imperialism or ruins of a past empire. The art historian Matthew Rampley has noted that Kiefer’s juxtaposition of the Sieg Heil gesture with ‘specific settings’ has been overlooked and requires further analysis.13

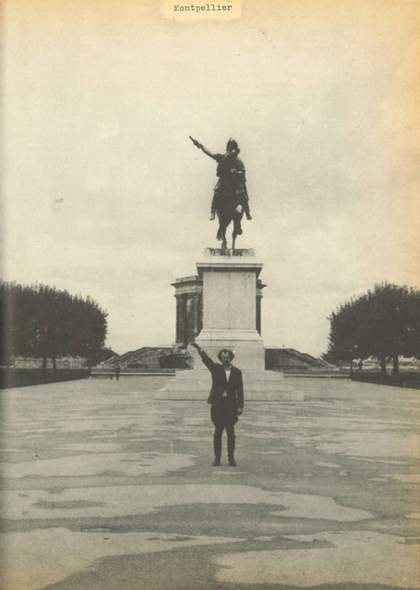

Fig.5

Anselm Kiefer

Occupations (Besetzungen) 1969

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer

While Switzerland and Italy were not ‘objects of military conquest’ by Nazi Germany, the Italian Social Republic from 1943 until 1945 was a puppet state (a German-dependent Fascist Italian state). France was an object of military conquest of course, although Montpellier, Sète and Arles were not part of the Wehrmacht-occupied northern zone. They came under the sovereignty of the Vichy Regime in the unoccupied southern ‘free zone’ that cooperated with Nazi Germany. This was until Operation Attila in November 1942 when the ‘free zone’ was invaded by German and Italian armies, with the Germans then effectively occupying southern territories and closely supervising French officials.

In addition to the first photograph in the 1975 photo-essay ‘Occupations’ showing Kiefer framed by the branches of a pruned plane tree, there is another photograph of the Place du Royale in Peyrou, Montpellier, in this provocative set of images. This one, less ‘heroic’ than the first, shows Kiefer half-heartedly giving the Sieg Heil salute in front of an equestrian statue of Louis XIV that depicts the king as a Roman emperor, a monument that relates to an ancient statue of Marcus Aurelius in the Capitol in Rome. Kiefer’s outstretched arm echoes that of the king on horseback, but the artist’s ‘Nazi’ is a bedraggled figure who does not match the monumental authority of the statue on a marble pedestal (fig.5). The raised-arm gesture of Louis XIV could point to the French occupation of conquered Spanish territories and Kiefer’s gesture similarly alludes to the German occupation of France during the Second World War. The grand esplanade of the Place du Royale also evokes German architect Albert Speer’s parade grounds in Nuremberg and the Nazi ambition of territorial expansion. Furthermore, the Sieg Heil gesture that recalls the terror of the Nazi regime indirectly draws out the hidden horror of the Peyrou site, which in the age of Louis XIV was not the pleasure ground it became in the reign of his successor, Louis XV. Rather it was an infamous place of horror: the Place de Grève, a barren table land where multiple executions of heretics against Rome took place and where the decaying corpses of Huguenot martyrs could be seen swinging from the gibbets on which they had been hung.

Fig.6

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

© Anselm Kiefer

Kiefer took many other photographs in Montpellier. Particularly interesting are those long-shots where Kiefer as a solitary figure salutes in the middle of tree-lined promenades (fig.6). These avenues could be ‘stand-ins’ for Speer’s parade grounds; the troops that collectively give the Sieg Heil salute in response to their political and military masters are substituted by the stark and sculptural pruned plane trees with their distorted clubbed branches that echo Kiefer’s gesture, almost as if he were commanding nature to obey. Other photographs in Heroic Symbols seem to suggest something else: the notion of the decline and fall of empire as conveyed by nature reclaiming imperial spaces. Rampley has argued that Kiefer’s photograph of the open space of the Forum Romanum at Paestum is ‘surely used to echo the fondness of the Nazis for mass rallies in large open spaces’.14 However, such an observation seems much more pertinent to Kiefer’s Montpellier photographs than the ones he made of ancient Paestum.

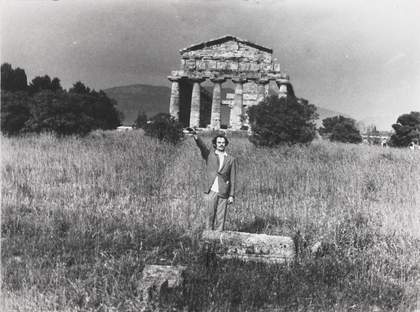

In one of the Paestum photographs Kiefer salutes on an ancient overgrown path at middle distance from the camera; to his right there is an isolated column of what appears to be a ruined temple. In another he salutes some distance in front of the ruined Temple of Athena, his feet concealed by an ancient fragmented stone block (Tate AR01171; fig.7). The land seems to be reclaiming the forum and one thinks of the line from T.S. Eliot’s epic poem ‘The Wasteland’ (1922) that reads ‘These fragments I have shored against my ruins’, although a more appropriate quotation comes from the biblical story of Lilith that reads ‘Over your cities grass will grow’. This second idea has recurred in Kiefer’s work for some time, and beyond its biblical context it comments on the transience of political authority and more specifically Hitler’s failed plans to transform Berlin into the new city ‘Germania’ (the capital of the so-called Thousand Year Reich). The biblical line was used as the title for Sophie Fiennes’s 2010 participatory documentary about Kiefer and his extraordinary studio complex in Barjac in southern France.

Fig.7

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

The phrase ‘Over your cities grass will grow’ connects to Kiefer’s interest in ruined cityscapes and ruins in landscapes as linked to experiences in his own life as well as the long Romantic tradition. Born in 1945, as a child the artist enjoyed playing in the ruins from the war and used to build small houses out of the rubble.15 This post-war experience clearly fed his Romantic imagination and the aesthetics of ruination in his work can be associated with the tradition of the ruin in German visual culture, one that includes Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), who frequently depicted Gothic ruins, and Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901), whose work often featured classical ones. Both of these artists’ names appear in inscriptions on various Kiefer artworks of the 1970s as well as in the Heroic Symbols artist books that he made in 1969.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the ruins of Paestum and the Forum Romanum in Rome that are explored in Kiefer’s photographs were the sources of inspiration for many artists and writers who participated in the Grand Tour, an educational rite of passage undertaken mainly by upper-class European men. The photographs Kiefer chose for publication in the 1975 photo-essay ‘Occupations’ could be seen as a Grand Tour of sorts, although a subversive one with darker pedagogical lessons. The emphasis on Kiefer saluting at Roman sites also conjures up thoughts of the Rome-Berlin axis of 1936 that became a military alliance in 1939 under the Pact of Steel. In the ‘Occupations’ photo-essay and the Heroic Symbols books, Kiefer explored other traces of the Roman Empire as suitable environments for his Nazi salute, especially the large Roman necropolis in Alyscamps outside the walls of the old town of Arles, France.

The connection to the Roman Empire is highly relevant in that Kiefer’s Nazi salute is reminiscent of Third Reich propaganda that sought to link both societies in a single historical continuum. As Rampley has written: ‘Indeed the juxtaposition of the Nazi salute and Roman monuments seems intended not to draw out a contrast, but rather to emphasize a certain continuity, especially given Hitler’s penchant for (albeit brutalized) classical monumental architecture’.16 Notably, Kiefer would go on to explore the Fascist neoclassical architecture of Wilhelm Kreis and Albert Speer in To the Unknown Painter, a series of works executed between 1980 and 1983.

Fig.8

Anselm Kiefer

Occupations (Besetzungen) 1969

© Anselm Kiefer

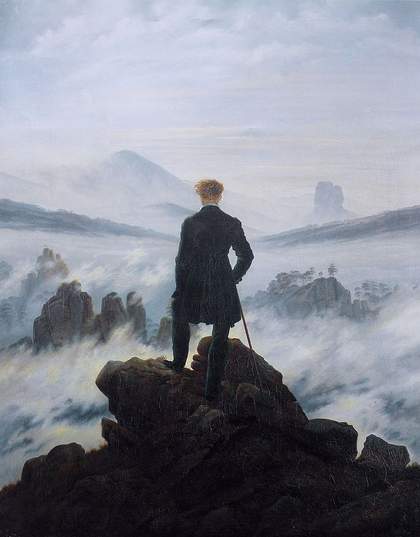

Fig.9

Caspar David Friedrich

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog 1818

Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg

Not all locations used for the Heroic Symbols photographs involved architectural traces of imperialism. As one of the four elements that frequently appear in Kiefer’s work, water in the form of puddles, lakes, rivers and seas all surface in Heroic Symbols. The most reproduced image in the literature on the artist, which was also published in ‘Occupations’, is the last one taken in Sète (fig.8) where Kiefer mimics Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog 1818 (fig.9). The salute to the sea could also be an allusion to the Kriegsmarine, the navy of Nazi Germany, which superseded the Imperial German Navy of the First World War and the interwar Reichsmarine, and it is well known that Hitler wanted to challenge Great Britain for naval supremacy. In this photograph Kiefer immediately conjures up a memory of this particular Romantic painting through the use of the Rückenfigur (the figure seen from behind), a compositional device closely identified with Friedrich’s canvases. By standing in similar riding boots to Friedrich’s wanderer, but on the rocky white foaming seashore at Sète, Kiefer creates a surprisingly successful substitute for Friedrich’s imaginative misty Saxon mountain scene. Furthermore, as the curator and art historian Mark Rosenthal has written: ‘In imbuing his photograph with the memory of how Germany was, Kiefer offers a critique of what it became in the 1930s and 1940s: what had been humble respect for nature in an earlier world has been replaced by strident pomposity in our own century.’17

According to the artist, between two and three hundred Heroic Symbols photographs documented the Occupations actions, but because Kiefer was a student at that time of their creation he could afford to enlarge only a fraction of the negatives.18 In moving to his new studio spaces in the Marais neighbourhood of Paris in 2007 and Croissy-Beaubourg in 2009, Kiefer had the opportunity to look over old work and found many negatives from the project that had never been developed. Enlargements were made from the remaining negatives and some have been utilised in more recent artworks, including an installation of seventy-six unique photographs mounted on lead and burlap in a steel box, also entitled Occupations, for his 2010 Gagosian Gallery New York exhibition Next Year in Jerusalem, as well as photo-paintings in the ARTIST ROOMS collection such as The starry heavens above us, and the moral law within 2010 (Tate AR01164).19