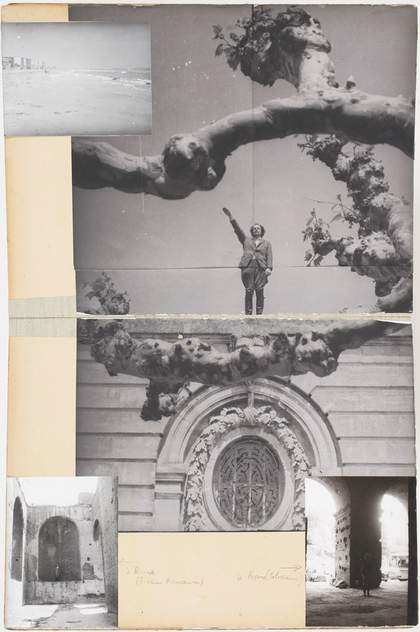

The Heroic Symbols photographs that document Anselm Kiefer’s 1969 performance Occupations were not seen in the public sphere until 1975, when some of those that had been taken in 1969, both in Kiefer’s Karlsruhe studio and ‘on location’ across Europe, were carefully selected and sequenced by the artist and published as a photo-essay ‘Occupations’ (in German ‘Besetzungen’) in issue twelve of the Cologne-based conceptual art journal Interfunktionen. This sequence of eighteen black and white photographs, in many respects a parody of a photographic travelogue, was laconically and provocatively captioned by the artist: ‘Anselm Kiefer. Zwischen Sommer und Herbst 1969 habe ich die Schweiz, Frankreich und Italien besetzt. Ein paar Photos’ (‘Anselm Kiefer. Between the summer and autumn of 1969, I occupied Switzerland, France and Italy. A few photos’).1 This caption, typed on used ribbon so that the text appeared faded, was set into two white rectangles at the top of the first photograph (fig.1), which shows the saluting Kiefer carefully framed by the pollarded branches of a plane tree to be found on the lower promenade of the Place Royale du Peyrou, Montpellier. This care in composition indicates that these photographs were not solely for the documentation of a performance, but also an exploration of the aesthetics of fascism. The first photograph is clearly composed for dramatic effect as the opening image of a provocative sequence. An architectural wreath, a window ornament of the monumental staircase that links the lower promenade (where the photograph was taken) to the upper promenade (where Kiefer salutes), is photographed in such a way as to give the illusion of it hanging naturally from the lower pruned branch. This low-angle shot is set up to make the sole saluting figure (Kiefer) seem heroic and emulates cinematographic techniques developed by Leni Riefenstahl for her films on Hitler, particularly Triumph of the Will (1935) in which Hitler is made ‘iconic’ on the speakers’ platform at Nuremberg through clever camera shots taken in pits dug in front of that platform.

Fig.1

Anselm Kiefer

Occupations (Besetzungen) 1969

Collage, black and white photograph

Published in the photo-essay ‘Occupations’, Interfunktionen, no.12, 1975

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer

Fig.2

Anselm Kiefer

For Jean Genet (Für Jean Genet) 1969 (pp.10–11)

Private collection

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Tom Powel

Six years earlier, shortly after his European travels, Kiefer had used the same photograph, minus the caption, on the front cover of his 1969 artist book Heroic Symbols II (Heroische Sinnbilder II) and it appears enlarged across two pages of his book For Jean Genet (Für Jean Genet) 1969 (fig.2), where it is juxtaposed with photographs of Rome and Sète that are in a smaller format. Other photographs that appeared in the 1969 books also appeared in Interfunktionen 12, but this 1975 journal issue only included his own photographs, whereas the books also contained appropriated photographs, his watercolours, as well as dried flowers and other materials. The iconic image of a saluting Kiefer framed by pruned branches that opens the Occupations sequence of photographs is so closely associated with the fate of that infamous last issue of Interfunktionen in which it appeared in 1975 that it is intriguing to discover that this striking photograph had already been utilised in his Heroic Symbols and For Jean Genet artist books in 1969 – although these were not seen in the public sphere until some three years after the Interfunktionen publication, when they were displayed in the exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Bilder und Bucher at the Kunsthalle Bern in 1978. Furthermore, this showing in Bern took place some eight years after Kiefer’s first solo exhibition at the Galerie am Kaiserplatz, Karlsruhe, in 1970, an exhibition also entitled Bilder und Bücher, in which, according to the critic Eckhart Gillen, these particular books were not included.2 This delay in image exposure, to use a photographic analogy, from the point of creation in the late 1960s to public dissemination in the mid-1970s seems significant, and the scandal that ensued after the publication of the Interfunktionen photo-essay indicates that the cultural-political climate for the reception of the work was still difficult, and in some ways perhaps even more problematic, than it might have been five or six years earlier.

Fig.3

Anselm Kiefer

Occupations (Besetzungen) 1969

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer

Fig.4

Anselm Kiefer

Occupations (Besetzungen) 1969

© Anselm Kiefer

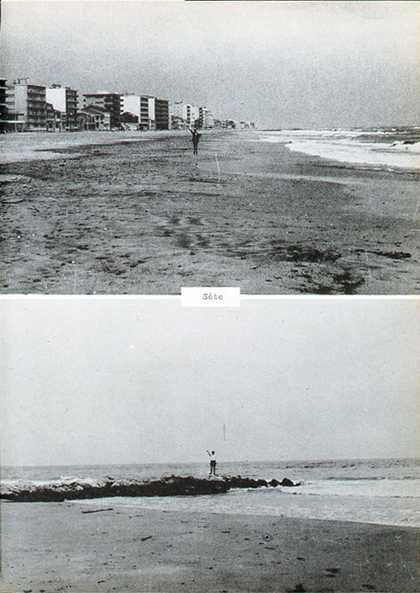

The clever ‘low-angle’ perspective of the memorable opening photograph of the Occupations sequence was not uniformly applied in the other photographs he selected for Interfunktionen. For instance, in two of the Sète seaside shots (fig.3), far less well known than the first and final Occupations / Heroic Symbols photographs of this photo-essay (figs.1 and 4), the saluting Kiefer is seen at a considerable distance, and in the first shot on a level plane, he is such a diminutive figure as to be almost Lilliputian. The mundane modern hotel blocks that form the backdrop to an expanse of empty beach only heighten the absurdity of taking this performance ‘on tour’ with no audience. A similar Sète photograph was also used in the top left-hand corner of the relevant bricolage pages of the For Jean Genet book where it is pasted over the key Montpellier photograph discussed above (fig.2).

The first much-reproduced photograph of the selection included in Interfunktionen (this time without the caption) was reutilised for the new Occupations series created in the build-up to two major 2010 exhibitions, one in New York at the Gagosian Gallery and the other in Copenhagen at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. One of these works shows how the negative has been enlarged to a scale over ten times that of the image reproduced in Interfunktionen magazine (fig.5). This enlarged Occupations ‘redux’ is on photographic paper on lead. The image is more distressed and faded than the Interfunktionen photograph and not unlike a work by an arte povera artist it seems to be in a state of alchemical transformation.3

Fig.5

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969

Photograph, lead, canvas

3900 x 2400 mm

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Charles Duprat

The journal Interfunktionen was founded in 1968 by Friedrich Heubach, but by 1974 it had been taken over by the critic and art historian Benjamin Buchloh in order to prevent it from being discontinued. As art historian Gwen Allen has pointed out, Buchloh strongly believed in ‘the political possibilities of the magazine as an alternative distribution form for conceptual art’,4 but his tenure was to be unexpectedly brief. Buchloh edited issue eleven of Interfunktionen, which was thematically devoted to artist books, with contributions by artists and writers including Germano Celant, Jörg Immendorff, A.R. Penck, Roman Jakobson, Lawrence Weiner, Dan Graham, Daniel Buren, Bruce Nauman and others. It also contained the first printing of Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers’s Racisme Vegetal. La séance, which was later turned into a separate edition of three hundred copies. Broodthaers was connected to the Düsseldorf avant-garde and had befriended Gerhard Richter, asking him to contribute the painting Eagle of 1972 (an imperial looking eagle that raised the spectre of Nazi power) to his magnum opus, the parodic Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, XIXth Century Section. Broodthaers, did not see any parodic humour in Kiefer’s work, however, and he would express outrage at the publication of issue twelve, objecting strongly to Kiefer’s ‘Occupations’. He angrily stated: ‘Who’s this fascist who thinks he’s an antifascist?’5 Broodthaers withdrew one of his artist books from publication under the mantle of Interfunktionen, about which Christine Mehring has written: ‘His reaction effectively cut off funding for the next issue and sealed the fate of what until then had arguably been the most important European art magazine since World War II. Dealers pulled their ads; curators and other artists conveyed their dismay, as did the magazine’s founding editor’.6 The journal ran out of steam and Buchloh has recounted how boxes of unsold copies (now highly sought after) resided in the basement of his sister’s Berlin apartment for years.7 Kiefer has said ‘Buchloh was very unhappy about the reaction. He is still unhappy.’8

Buchloh first encountered Kiefer in the Cologne art scene of the early 1970s. At this time Buchloh was working as an assistant director at the Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, and in 1973 Kiefer was taken on and given a solo exhibition by the art dealer Michael Werner, the first of six to be staged in the Galerie Michael Werner in Cologne before 1979. Until 1969 Werner had been based in Berlin, and his first gallery, Werner & Katz, had opened in 1963 with the first solo exhibition of Georg Baselitz, a show that caused such a sensation it led to two of Baselitz’s paintings being seized by the public prosecutor on grounds of obscenity. This included The Big Night Down the Drain (Die große Nacht im Eimer) of 1962–3 (Museum Ludwig, Cologne), which featured a grotesque masturbating figure, one that in Baselitz’s remix version of 2005 is more clearly defined as Hitler. Werner represented both Baselitz and Kiefer, but Buchloh was more interested in Kiefer. Of encountering Buchloh in Cologne, Kiefer has said: ‘I met him several times in the Michael Werner gallery. He was connected to Werner and so I said take this [the eighteen Occupations photographs]. He wanted [the artist book] the Flooding of Heidelberg, but I said no, this is better.’ Buchloh, who had been impressed by Kiefer’s early books, agreed to publish the Occupations photographs, and argued that it was ‘a real working through of German history. You have to inhabit it to overcome it’.9

Buchloh had strong disagreements with Heubach, the previous editor and founder of Interfunktionen, regarding which artists the magazine should support. For instance, unlike his predecessor, he was not a fan of Wolf Vostell, and Buchloh has said: ‘The Kiefer project was a response to his [Heubach’s] support of all these German body artists. Now that [Occupations] was German body art’.10 Elaborating on this point, Buchloh has stated that Kiefer inflected performance art with ‘a regionally and nationally specific gesturality, and that was really quite politically appropriate for us, as a German magazine’.11 In the critical storm that followed the publication of Interfunktionen 12 Buchloh ‘went to bat for the young Kiefer against his pet subject Broodthaers’,12 but this position was not sustained, and he would later become one of Kiefer’s most vociferous critics, suggesting that his art was guilty of ‘retardation and regression’ especially after the scandal concerning the showcasing of Kiefer’s work, along with that of Baselitz, in the West German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1980.13 Here the two artists had been nominated by the Biennale Commissioner Klaus Gallwitz, who had known Baselitz since the 1960s and Kiefer since the early 1970s through his organisation of the experimental series of exhibitions 14 mal 14 at the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden. None of Kiefer’s Heroic Symbols photographs, paintings or artist books were shown at the Biennale, although seventeen of his books, many responding to National Socialist aesthetics and myth-making, and various large paintings and composite woodcuts such as those from the 1978 series Ways of Worldly Wisdom, were exhibited. Baselitz’s contributions were much fewer in number but notably did include his first sculpture Model for a Sculpture 1979–80 (Museum Ludwig, Cologne), a half-reclining Hitler-like figure, which like some horror version of Pinocchio seemed to emerge organically from the roughly hacked mass of limewood blocks, its stiffly raised right arm suggestive of the Nazi Sieg Heil salute. Art historian Lisa Saltzman has noted that Baselitz’s sculpture bore a ‘striking resemblance’ to Kiefer’s Heroic Symbols paintings and the ‘Occupations’ photo-essay, ‘albeit in a fundamentally different form’.14

Dark mythological and historical themes and the ‘wood’ as both subject and material dominated the German pavilion, which stood out as a kind of arboreal tabernacle, leading critics such as Werner Spies (later a strong champion of the artist) to accuse Kiefer of providing the spectator with ‘an overdose of the Teutonic’.15 By now, neither Baselitz nor Kiefer were strangers to controversy, although at the time Kiefer was taken aback by the number of German critics who accused them both of flaunting Germanness in an unacceptable way, failing to acknowledge the deconstructive nature of the work.16 Saltzman has speculated that Buchloh’s later critical aversion to Kiefer might have been due to the collapse of Interfunktionen.17 Equally, it could be put forward that Buchloh was at least in part following the critical line of many of his countrymen during the Biennale by arguing that Kiefer’s delving into the storehouse of German myth, combined with his use of ‘ancient teutonic graphic techniques’,18 was regressive at best and borderline neo-fascist at worst. Perhaps Buchloh also felt that Kiefer had moved too far from the photoconceptualism that first attracted him to the artist and towards large-scale painting and woodcuts, media he had long believed to be obsolete irrespective of Kiefer’s unconventional treatment of them. Instead, Buchloh has consistently promoted Gerhard Richter (a painter who in his opinion has a laudable ‘anti-painting’ impulse) over Kiefer as an artist far more capable of leading us to reflect on questions of post-war Germany.19 In a 2013 interview, while also reflecting on Buchloh’s negative critical treatment of Beuys, Kiefer has said wryly of the critic: ‘I think he still thinks I am a Neo-Fascist … There is this German attitude to be moralistic and prescriptive … And Buchloh is a little bit super German.’20

Buchloh has suggested that Richter’s reflection on the fate of the Baader-Meinhof terrorist group in his 1988 series of paintings October 18, 1977 is evidence of ‘a larger project of understanding the formation of post-war German identity by addressing second and third generations of that historical trajectory rather than by returning to the actual events of the Nazi past as they were staged in Kiefer’s work’.21 However, this point ignores the fact that Kiefer also responded to the Baader-Meinhof group in his ‘attic’ painting Parsifal III 1973 (Tate T03405), where some of the names of the faction are inscribed in the painting, almost concealed by paint like half-erased graffiti, and effectively incarcerated by the dark wooden interior. Kiefer has said ‘When the Baader-Meinhof actually started murdering people I thought it was just like the Nazis again. They felt they could be judges just as Hitler did. Indirectly all of this must have affected my art, but not directly’.22 That Kiefer seemed to allude to the imprisonment of members of the Red Army Faction and was possibly not wholly unsympathetic to their fate, irrespective of the remark cited above, is strengthened by an inscription that Tate curators later discovered on the reverse of the painting. Kiefer recalled this moment: ‘Later they [Tate curators] found the phrase “there is torture in German prisons” written on the back of the picture and asked me what it meant. It actually has nothing to do with the art, but it obviously showed I cared about what was going on.’23 According to Buchloh, however, Kiefer has lacked commitment to contemporaneity – an active commitment that Buchloh was seeking in art – and his criticism has even gone so far as to suggest that Kiefer and other artists associated with the label ‘Neo-Expressionism’, a label that Kiefer dislikes,24 attempted to commoditise history, fuelling a market for paintings that explored the symbols and spectacle of National Socialism, even if this exploration was critical.25 Interestingly, both Kiefer and Buchloh are admirers of the philosophy of Theodor Adorno, but it is clear that Buchloh ultimately felt Richter’s work provided a better visual corollary to his own theoretical position, a position informed by the Frankfurt School critical theory to which Adorno is central.

In the early 1980s Kiefer was championed by the critic Donald Kuspit, who famously wrote a riposte to Buchloh’s ‘Marxist blitzkrieg’ titled ‘Flak from the “Radicals”: The American Case Against Current German Painting’. In this essay, Kuspit argued that in confronting their fathers’ generation, Kiefer, Baselitz and other ‘new German painters’ were laying ‘to rest the ghosts – profound as only the monstrous can be – of German style, culture, and history, so that the people can be authentically new … They can be freed of a past identity by artistically reliving it’.26 This comment is not so different from Buchloh’s positive view of Kiefer’s Occupations performance and photoconceptualist project as ‘inhabiting history’ to ‘overcome’ it, but Buchloh departs from Kuspit in arguing that by turning to painting Kiefer was regressing to the obsolete conventions of a ‘neobourgeois’ art. The early 1980s debate between Buchloh and what he negatively referred to as ‘Neo-Expressionism’ and Kuspit and what he alternatively dubbed ‘New German Painting’ (thereby avoiding the regressive connotations of the former term), with each critic co-opting an artist to shore up their own critical positions (Buchloh/Richter and Kuspit/Kiefer), in many regards reprised the terms of a much earlier interwar debate: that concerning the ideological position and commercial value of expressionism that took place between the Marxist critics Georg Lukács (much admired by Buchloh) and Ernst Bloch (closer in spirit to Kuspit).27

While Kiefer no doubt appreciated the critical support of Kuspit and others at the time, his persistence in revisiting Occupations in various ways and media would seem to indicate that he does not think that such ghosts can or should be laid to rest. In another influential essay on Kiefer the cultural historian and theorist Andreas Huyssen astutely identified why the artist’s ‘Occupations’ photo-essay upset so many people: ‘The problem is in the very usage of those icons, in the fact that Kiefer’s images violate a taboo, transgress a boundary that had been carefully guarded, and not for bad reasons, by the post-war cultural consensus in West Germany: abstention from the image-world of fascism, condemnation of any cultural iconography even remotely reminiscent of those barbaric years’.28 Yet Kiefer was not the only artist to re-enter the ‘image-word of fascism’. Between the mid-1950s and the early 1970s artists as diverse as Joseph Beuys, Georg Baselitz, Blinky Palermo, Marcus Lüpertz, Wolf Wostell and Gerhard Richter, among others, had in various ways attempted to critique the ground zero of visual amnesia and confront their fathers’ generation through a dismantling of the apparatus of repression, but none of them did so as directly as Kiefer. As art historian Daniel Arasse has observed, ‘Kiefer was the first to tackle the representation of Nazism head on, using his own body’.29 Furthermore, Kiefer’s apparent compulsion to repeat the gesture in different contexts provided additional shock value.

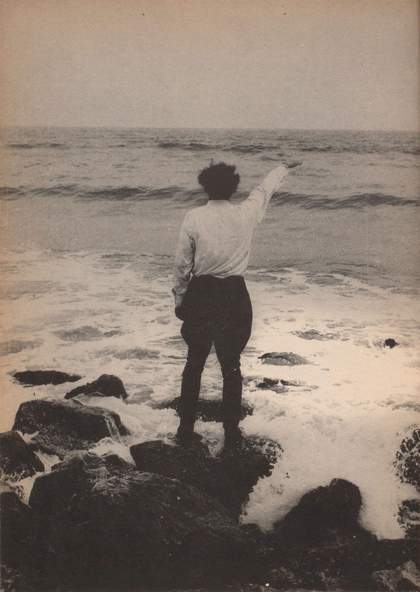

The edginess and difficulty of Kiefer’s project comes from a particular ambivalence that is heightened by the multiple meanings of the word ‘occupations’, which is a word that has even more lexical possibilities and nuances in the original German (Besetzungen). The term can allude to, among other things, territorial expansionism, cathexis (a psychoanalytic term for ‘holding fast’), the casting of a play in the theatre (or the assumption of a role in a play) and student sit-ins.30 In terms of iconography, Besetzungen may also allude to a process of symbolic transference (occupations of ‘meaning’ in the sense of the political contamination of symbols). This is relevant to the last photograph in the Interfunktionen spread, which shows Kiefer standing on the shore and saluting the sea at Sète, an image that apes an iconic painting of the Romantic sublime, Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog 1818 (Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg), in a way that suggests that National Socialism had some roots in Romanticism and that this particular Romantic artist’s work was appropriated for Nazi propaganda. It is worth remembering that many of Friedrich’s artworks created before 1815 were motivated by contemporary political issues, not least the ‘occupation’ of German-speaking lands by Napoleonic troops, and can be understood as a form of symbolic patriotic propaganda that was therefore easily absorbed later by the National Socialist propaganda machine. Friedrich was discredited in the post-1945 period up until the early 1970s, when art historians such as Werner Hoffmann rehabilitated and defended his work against such anachronistic political associations with National Socialism.