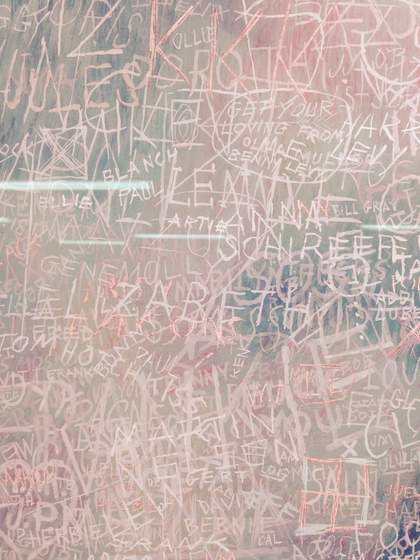

Fig.1

Bernard Perlin as war artist-correspondent, Cairo 1943

Unidentified photographer

Collection of Michael Schreiber

Bernard Perlin is a challenging artist to place. Early in his career, he was often viewed as an epigone of Ben Shahn, the prominent American social realist with whom he worked in the early 1940s. During the Second World War, Perlin produced classic posters bristling with patriotic fervour, before seeking adventure as an artist-reporter (fig.1), travelling around Europe, the Middle East and the Far East and documenting the war and its aftermath. At mid-century, in an era otherwise dominated by abstract expressionism, he became associated with the figurative magic realists,1 especially a prominent sub-circle of gay artists headed by Paul Cadmus and Jared French.2 In the 1970s and 1980s, dissatisfied with the art world, he largely withdrew from painting and exhibiting, before enjoying a flourish of productivity in his final years (he died in 2014), creating gauzy canvases that blended lessons imbibed from both abstraction and figuration. At the end of his life, the artist – prone to self-doubt – was able to take pride in this long, wending artistic path. ‘People always ask me why my paintings are so different [that] they might have been done by several artists’, he told an interviewer when in his nineties. ‘Well, I’ve gone through many different phases of life – it’s been full of changes, so why would I stick to one technique?’3

Orthodox Boys 1948 (Tate N05956; fig.2), painted as Perlin turned thirty, came at a critical point in the circuitous trail of his career. As Erika Doss illuminates in her contribution to this project, by the late 1940s Perlin was emerging from an intense period of wartime commissions; first from the United States government’s Office of War Information (OWI), and subsequently from Fortune and Life magazines.4 Perlin would continue to do commercial work throughout the 1950s, including impressive spreads on subjects ranging from transitions in American farming and manufacturing to rocket launches from Cape Canaveral. While he took ‘pleasure and pride’ in these assignments, noting with some relief that he could look back on them and ‘not wince’,5 by 1948 he wanted to set his own subjects and establish himself as a serious easel painter.

Fig.2 Bernard Perlin

Orthodox Boys 1948

Tempera on board

762 x 1016 mm

Tate N05956

© Bernard Perlin

Photo © Tate

With Orthodox Boys Perlin began to define his mature practice as a painter, without depending on commissions. At the time he was living in a tenement flat on New York’s Lower East Side, and painted scenes – like The Street 1947 and Vacant Lots 1948 (both private collections) – which reflected his surroundings. Drawing upon his experience as a war reporter, in which he shunned the camera and honed his ability to recall scenes from memory, Perlin set out to capture vignettes of street life in post-war New York.6 Liberated from the factual imperative of reportage, however, he found a new freedom to structure his canvases imaginatively, introducing elements of mystery and allegory.

Pride and prejudice in Jewish New York

An anxious, apprehensive mood pervades Orthodox Boys. Two Jewish adolescents share a furtive conversation as they wait for the subway in front of a newspaper kiosk at Canal Street Station in Lower Manhattan. Perspective is collapsed, almost to the point of inscrutability, and the sense of constriction emphasises the tremulousness of the wary pair. As Samantha Baskind explains, having covered the fallout of the Second World War around the globe, Perlin returned to the United States to find that anti-Semitism persisted on the home front, despite the harrowing revelations about the Holocaust.7 Unmistakably Jewish in appearance, with one clutching a Hebrew text, the boys glance guardedly around the corner for signs of danger. What lurks at the edge of the composition, however, is not some schoolyard bully, but the sinister spectre of recent history. The grim train tracks at the margin of the picture threaten to take these young Jews not to the safety of their homes but towards the tragic fate that met millions of Europe’s Jews just a few years earlier. The swastikas scratched into the surface of the painting puncture any illusions that the young Orthodox boys – or indeed we, the viewers – might have about the security of Jewish life. Anti-Semitism, Perlin’s painting announces, remains etched into the fabric of modern life, even after the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Yet anti-Semitism has by no means won the day in this painting. Whatever danger may lie around the bend, these boys stand plainly Jewish, in plain sight. The dense thicket of graffiti on the wall behind them testifies to the allied victory in the Second World War. One line declares ‘Kilroy was here’, the ubiquitous slogan of allied soldiers, while in another spot Kilroy’s famous caricature appears with the cheeky alteration, ‘Clem was here’. It is tempting to read this as a reference to the art critic Clement Greenberg, who was metaphorically, if not literally, scrawling his name across the New York art scene at this time. Elsewhere, ‘USS Swordfish Dec 21, 1946’, pays tribute to one of the US Navy’s most successful submarines, sunk by the Japanese in the waning months of the war. There are a handful of swastikas, but their effect is less than triumphant. One is drawn backwards by an incompetent hooligan, as if something has been lost in translation from Germany to America. Two more have been neutralised by subsequent graffitists, who have extended the lines of the swastikas to form simple, anaesthetised squares (fig.3, lower right). Larger than any swastika, the letters ‘KKK’ – the abbreviation for the American white supremacist organisation the Ku Klux Klan – are prominently scraped in red onto the upper left of the kiosk wall (fig.3, top). Fascism may have been defeated abroad, but homegrown racism and prejudice remain.

Fig.3

Bernard Perlin

Orthodox Boys 1948, detail of swastika and KKK graffiti

Tate N05956

© Bernard Perlin

Photo © Tate

While the yeshiva boys appear filled with trepidation, behind them lie more assertive marks of Jewish presence. The wall is brimming with identifiably Jewish names (as well as a smattering of Irish and Latin American names). Many of these, as discussed in the next section, constitute winks and nods to the artist’s friends and family.8 Others may be simply intended to induce a chuckle, like the words of one Jewish lothario: ‘Get your loving from Benny Levy’. There is also a Star of David as well as the word ‘Israel’, perhaps freshly scrawled in celebration of the Jewish state that was founded in 1948. Elsewhere, ‘The Mightie Atoms’ might be the name of a street gang named after the Jewish strongman Joseph Greenstein, known as ‘The Mighty Atom’, who could hammer nails with his bare hands. Meanwhile, ‘Bugsy was here’ could represent an homage to the infamous Jewish gangster, Bugsy Siegel, who had been killed in 1947.

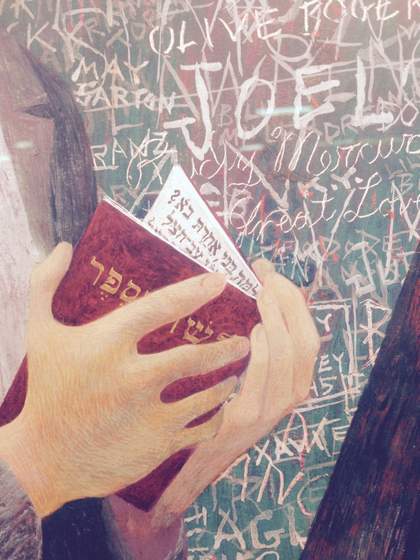

With some effort, it is not only possible to decipher the text on the walls but on the book cradled by one of the students (fig.4). Appropriately enough, the volume has the Hebrew word ‘sefer’ (‘book’) stencilled on its cover. While the rest of the title is harder to make out through the boy’s hands, the full text might read ‘lashon ha-sefer’ (‘the language of the book’). Inside, if we look closely we can make out a line in Hebrew, which might be translated as ‘Why, my son, did you come late?’. Leaving aside for the present the meaning of these words – which Baskind deftly explores – Perlin seems intent on emphasising that these boys, and indeed he himself, are ‘people of the book’.9 Yet image does not stand in opposition to text, as strict interpretations of the second commandment might have it. Instead, writing and painting belong to a single, consummately material act of inscription. At their heart, Perlin seems to suggest, they are both meaningful forms of mark-making. As a Jewish artist, Perlin does not so much defy Judaism’s textual heritage as extend it in new ways. He might well have agreed with the words later penned by the Jewish songwriter Paul Simon: ‘The words of the prophets are written on the subway walls and tenement halls’.10

Fig.4

Bernard Perlin

Orthodox Boys 1948, detail of Hebrew book

Tate N05956

© Bernard Perlin

Photo © Tate

Writing on the wall

The expansive green wall of the kiosk not only provided Perlin with a conceptual chalkboard on which to work out his self-conception as a Jew: it also offered a space to map out many other parts of his life, from family relationships to professional contacts, love affairs and artistic influences. Perlin was hardly being hyperbolic when he declared that the painting included the names of ‘everyone I ever knew up to that point’.11 Thanks to the assistance and encyclopaedic knowledge of Michael Schreiber, a close friend of the artist in his final years and the curator of his estate, it is possible to pinpoint a number of these references, and speculate in an informed way on a good many more.12 This represents the first attempt to undertake such a close study of the inscriptions in this painting, a daunting but rewarding task that has the potential to open up further avenues for future scholars.

A good place to start is to look for the artist’s own name. Intriguingly, there is no signature per se amid this welter of names. What we do find is the name ‘Xavier’, potentially a nod to Perlin’s teenage years when he decided to switch his middle name from Jerome to Xavier, ‘which he thought sounded more exotic’. This playful, highly personal sensibility characterises many of the references, which frequently include in-jokes, nicknames, abbreviations and deliberate misspellings only intelligible to those ‘in the know’. The memory of his father Davis Perlin – who died in 1929 when Bernard was just twelve – may account for the inclusion in the painting of the word ‘Dada’ (although it may also be an art historical quip referencing the famous modern art movement), and that of his grandmother by the affectionate Yiddish transliteration ‘Bubby’. Perlin’s mother is remembered by her full first and maiden name, Anna Schireff, which testifies to her abiding influence. ‘Janet’, according to Schreiber, might refer to Perlin’s sister Jeanette, who died aged nineteen in 1932.13 ‘Mildred’ appears twice, possibly referring to Mildred Perlin Klein, the artist’s older sister, while ‘Nat’ could be her husband, Nathaniel Klein. The names of their children, ‘Janice’ and ‘Don’ (Donald) are also present. According to Schreiber, Don ‘remembered as a young boy seeing Bernard working on the graffiti for Orthodox Boys on a trip to Miami’. Other family members to whom allusions are made are an aunt nicknamed ‘Bloomer’, cousin ‘Sylvia’ and her husband ‘Chesty’ (Grossman), and relatives ‘Irv Milkin’ and ‘Meyer’ (Milkin).

Friends from Perlin’s early life in Richmond, Virginia, are suggested by ‘Milton’ [Perel] and ‘Lanier Buford’, one of the artist’s first crushes. ‘Selma [Sidenberg]’ likely refers to Perlin’s first girlfriend, at age fourteen, for whom he painted a bouquet, a motif he took up again throughout his career (see, for instance, Flanders Field 1970/2011, collection of the Perlin estate). ‘Catherine Gravet’ is the name of Perlin’s first female sexual partner, whom he met when he moved to New York. The names of male lovers are far more common, including artists (‘Kenneth’ (Kenneth Hayes Miller), ‘Syd’ (Sydney Engelberg)), actors (‘Cliff’ (Clifton Webb)) and ballet dancers (‘Dick Reed’). Ballet, championed by Perlin’s patron Lincoln Kirstein, became a large part of Perlin’s life in New York at the time. ‘Drew’ may refer to Perlin’s lover Robert Drew, who designed the costumes and set for one of Kirstein’s ballet performances on which Perlin assisted.

Perlin’s first and most serious partner up to the time he painted Orthodox Boys was ‘Alvin’ (Wolfson), with whom he lived from 1938 until 1943, although their relationship was platonic in its later years. The full inscription, ‘Alvin loves Josie’, seems to take this relationship history into the present, when Alvin was dating ‘Joe Precker’, whose name appears elsewhere in the painting. Perlin’s decision to disguise ‘Joe’ with the female name ‘Josie’ is a telling obfuscation. While Perlin, like many friends in the city at the time, lived an openly gay life within certain circles, it would have been dangerous to draw attention to a homosexual union, let alone to ‘out’ two close friends to the general public. While Perlin felt comfortable painting explicitly Jewish people and subjects – which a number of painters of that era did not – he was hesitant at the time to depict explicitly gay subjects for public consumption. In fact, openly expressing Jewish anxiety in Orthodox Boys may have provided a cathartic but clandestine way to articulate anxiety about living as a gay man in mid-century America.

Fig.5

Glenway Wescott and Monroe Wheeler at Stone-Blossom, their country home, c.1947, with Perlin’s silverpoints of Lloyd Wescott, W. Somerset Maugham and E.M. Forster hanging above the fireplace

Unidentified photographer

Collection of Michael Schreiber

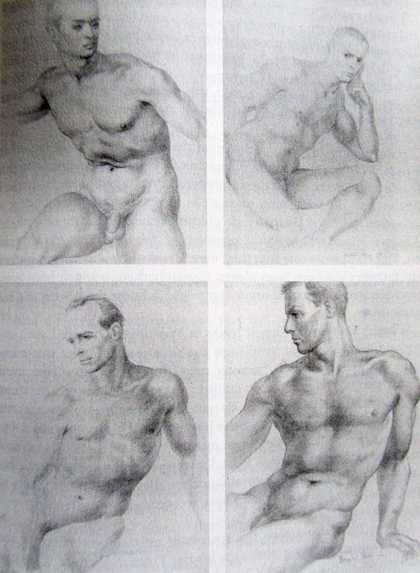

If Perlin hesitated to announce his sexual identity to the wider public, he was confident being himself among a wide network of friends. Many of these confederates were associates of the well-known writer Glenway Wescott (‘Glen’), a close friend and sometime lover of Perlin’s. The artist was a visitor at the country home of Wescott and Monroe Wheeler (a leading figure at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York), in which Perlin’s silverpoints of Lloyd Wescott, W. Somerset Maugham and E.M. Forster hung above the fireplace (see fig.5). Indeed, the Westcott family were so important to Perlin that they can be tied to a trail of references in Orthodox Boys, including Glenway’s sister ‘Elizabeth’, sister-in-law ‘Barb’ (Barbara), niece ‘Debo’ (Deborah) and even their maid ‘Ethel’. For a long time, Glenway lived in a ménage with Wheeler and the photographer George Platt Lynes (the possible sources of the initials ‘M.W.’ and the name ‘George’). Years earlier, in 1941, Perlin made nude silverpoint sketches of this troika in addition to Lincoln Kirstein, imagining them as a foursome of mighty mythological figures (fig.6).

Fig.6

Bernard Perlin

George Platt Lynes, Lincoln Kirstein, Monroe Wheeler and Glenway Wescott as mythological figures c.1941

Collection of John Connolly and Ivan Ashby

Reproduction from David Leddick, Intimate Companions: A Triography of George Platt Lynes, Paul Cadmus, Lincoln Kirstein and their Circle, New York 2001, p.171

For his part, Kirstein (‘L.K.’) could be tied to a further, intersecting orbit of names. In addition to Kirstein’s sister ‘Minna’ (Curtiss), Perlin also pays homage to Kirstein’s wife Fidelma (‘Fido’), the sister of Paul Cadmus and herself an accomplished painter. Given these connections to so many family and friends, it is little wonder that Kirstein had such a keen interest in Orthodox Boys, buying it for himself and later arranging its acquisition by Tate.14 Perlin remained ever grateful to those who helped him – even if their relationship soured, as his tie to Kirstein eventually did – and he made a point of incising the names of several other patrons into his painting. ‘Vincent’ could refer to Vincent Price, a noted actor who gave Perlin one of his first commissions: to paint a mural of Adam and Eve in Price’s bathroom. ‘Tom’ (Mabry) was a prominent figure at MoMA as well as an occasional lover, who first introduced Perlin to Ben Shahn, leading to his employment at the OWI.

A multitude of other friends and acquaintances testify to Perlin’s ever expanding social contacts in this period, especially in the arts. ‘Lenny’ could indicate the famed composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, ‘Chuck Howard’ was a fashion designer, as well as a romantic partner of both Perlin and Lynes. A long-time friend, Howard later bought the property adjacent to Perlin’s in Ridgefield, Connecticut. ‘Iris’ (Mabry), the sister of Tom Mabry, danced for Martha Graham, while Frederick Ashton (suggested by the inscription ‘-shton’) was a ballet dancer and choreographer. ‘Butch’ (Fred Melton) formed a printing company that produced bespoke wallpaper, including a dazzling pattern designed by Perlin, which Perlin later used to decorate his guest bedroom (fig.7).15 ‘Leo’ (Lerman) and ‘Walt[er] Bernstein’ were writers, ‘May Sarton’ and ‘Kid Posner’ (David Louis Posner) poets, and ‘Larry Babcock’ a war reporter who helped Perlin find work as an illustrator. ‘Willie’ was probably the novelist W. Somerset Maugham, of whom Perlin sketched a much-reproduced likeness. ‘Addie Lubell’ (Adeline Lubell Naiman) was an editor who attended the opening of Perlin’s first one-man show, The Work of Bernard Perlin at M. Knoedler & Co., New York, in 1948, at which he exhibited Orthodox Boys (fig.8). Later, she had the unenviable task of reading to him a less than sanguine review in the New York Times.16

Fig.7

Bernard Perlin

Wallpaper c.1963, shown in the guest bedroom of Perlin’s home in Ridgefield, Connecticut, 2015

Artwork © Bernard Perlin

Photo © Aaron Rosen 2015

Perhaps most importantly, the walls of Orthodox Boys became a place for Perlin, on the threshold of his mature period, to stake his claim in the art world, in the company of those who had helped him along the way. The names ‘Margery’ and ‘Goodwin’ could pay homage to Marjorie Goodwyn, his encouraging high school art teacher in Richmond, Virginia. As Schreiber notes, ‘Goodwin’ may refer instead or in addition to Philip Goodwin, who designed MoMA’s first permanent home in 1939, as well as his nephew John Goodwin, a friend of Perlin’s in this period. Perlin had a special affection for MoMA, cemented in 1948 when it purchased his painting Lovers 1946, his first museum acquisition. Peers from New York during the late 1930s and early 1940s are suggested by the names ‘Bill Gray’ (William Cole Gray, Jr), a gay artist from Perlin’s hometown, ‘Olga Muller’, ‘Martin Nelson’, and ‘Dick’ (possibly Dick Dawson). A particularly noteworthy classmate from his time at the Art Students League was ‘Ed Hewitt’, who came from a wealthy family whose Upper East Side estate is now the Cooper Hewitt Museum. Through Hewitt, Perlin met both ‘Paul’ (Cadmus) in 1939, and ‘George’ Platt Lynes in 1940, both of whom are also duly inscribed in Orthodox Boys. ‘Henry’ may refer to Henry Koerner, a colleague at the OWI and another artist whose work was often shown in exhibitions of magic realism.

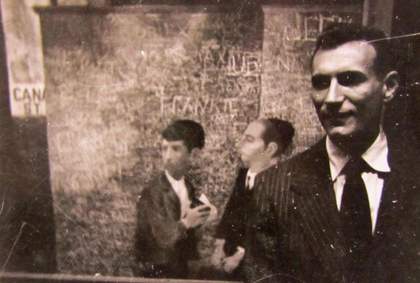

Fig.8

Bernard Perlin in front of Orthodox Boys 1948 at the opening of his first one-man show at M. Knoedler & Co., New York, 1948

Unidentified photographer

Collection of Michael Schreiber

In a biographical form he filled out in the mid-1950s, Perlin was asked to list his most influential teachers. He wrote: ‘In order chronologically but also in significance (perhaps due to the growing-up process): 1. Wm [William] C. Palmer 2. Harry Sternberg. 3. Ben Shahn’. All three – ‘Palmer’, ‘Harry’ and ‘Ben’ – appear in Orthodox Boys. Palmer taught Perlin at the Art Students League in 1938 and was, in Perlin’s words, the ‘first teacher who made any sense’.17 He had even higher praise for ‘Harry’, who taught him at the League in 1940, and whom he called ‘a remarkable Teacher and artistic Finish[ing] School for [becoming] … a professional artist – to think – and to relate all the tangents of one’s training and one’s young being into becoming a serious artist.’18 Writing with characteristic candour, Perlin called Shahn ‘the greatest influence without a doubt, I think (and the hardest to shake, too)’.19 Fittingly, whether consciously or unconsciously, Perlin includes the name ‘Ben’ twice in his graffiti, seemingly unable to stop the name from rattling around in his head. Present too is Shahn’s wife ‘Bernarda Bryson’ (Shahn), a well-respected artist and illustrator, as well as Shahn’s art dealer, ‘[Edith] Halpert’. As much as Perlin wished to ‘wriggl[e] from under the marvelous but repressive influence of Ben Shahn’,20 he no doubt hoped to meet with similar success, both critically and financially.

Scratching the surface

While Perlin’s graffiti can, as we have seen, be deciphered literally, it also makes a bold visual statement. The decision to render modern graffiti using the ancient practice of sgraffito – scratching through one layer of paint to reveal another – constitutes an art historical joke that clearly appealed to the artist. It also reveals Perlin’s quite serious interest during this period in recovering and reinvigorating the artistic practices of the past. As the curator Jeffrey Wechsler explains, during the 1930s and 1940s there was a fresh wave of interest in Renaissance techniques of tempera painting:

A crucial point of dissemination of Renaissance techniques was the Yale Art School. Daniel V. Thompson and Lewis E. York were both Yale professors who proselytized for fine techniques, and extolled the virtues of egg tempera. Thompson produced an authoritative translation of Cennino Cennini’s handbook of technique, and updated and enlarged on it in his 1936 The Practice of Tempera Painting.21

From Yale, these techniques rippled outwards to New York, finding prominent evangelists in French, Cadmus and Shahn, who all became role models for Perlin. In Orthodox Boys, Perlin uses the tempera technique to maximum effect. On the one hand, he was able to scratch through the wall’s top layer of dry green to expose underpainting in red and white. This rough, angular act of incision plays off nicely against the precise, delicate brushwork that comprises the figures. Lines seemingly formed by single hairs on Perlin’s brush tenderly curl around the facial features of the boys, making even their individual follicles stand out. Faint traces of pale green come through the boys’ nearly translucent flesh. In the kind of irony Perlin enjoyed, an age-old technique allowed him to conjure a distinctly modern sense of uncanniness.

If Perlin’s choice of technique seemed to set him squarely within the company of Shahn and other mentors, at the same time he selected a motif that allowed him to flirt with other trends taking root in post-war America. As the art historian and curator Robert Cozzolino acutely comments, in Orthodox Boys ‘abstraction and realism inform one another but cannot be easily pried apart. The multicolored words … form a buzzing assertion of surface behind the figures.’22 This insight is unpacked further in the essay ‘Bernard Perlin: Europe’s American’, which considers how Orthodox Boys responded to, and even absorbed, some of the lessons of the abstract expressionists.23 Ultimately, however, Perlin knew who his allies and audiences were, and their names are scattered liberally across his composition. Yet he did not paint in order to cement an orthodoxy, whether painterly or otherwise. He wanted to carve out his own name, on his own terms. And Orthodox Boys was his manifesto.