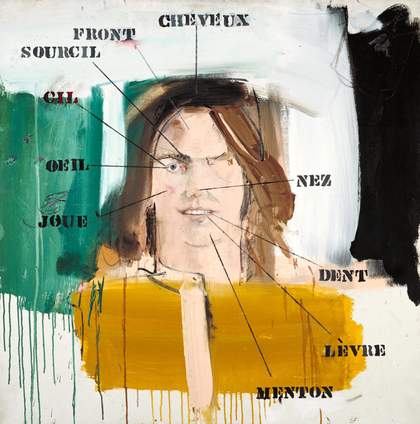

Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson (Tate T00522; fig.1) was painted by the American artist Larry Rivers (1923–2002) in 1961, during a stay in Paris. Under the guise of a humorous portrait of his wife, the artist proposed a new mode of figuration at a time when post-war abstraction was still largely dominant – one that was reflective of the ‘linguistic turn’ of the 1950s and 1960s. As this essay will unveil, his association of French words and the female face contained an unexpected political resonance in the context of transatlantic artistic exchanges and decolonisation war.

Fig.1

Larry Rivers

Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson 1961

Tate T00522

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Photo © Tate

Oil on canvas

749 x 749 mm

Fig.2

Clarice Rivers in the 1960s

Unidentified photographer

Larry Rivers Papers, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University

Courtesy the Larry Rivers Foundation

In this painting Rivers playfully organised a contrast between the heavily textured oil painting and the diagrammatic aspect of the composition. On the surface of the canvas, four large, abstract, coloured shapes define a central space from which the head of a woman emerges. The paint has been expressively – and somewhat carelessly – applied, with powerful brushstroke traces, drips of wet paint, dark stains soiling the colours, and even fingerprints visible on the right side of the face. In places the canvas shows underneath the shallow, diluted paint; elsewhere, thick impastos of colour protrude, giving the sitter’s hair, for instance, more texture. Yet the woman’s face emerges in a very recognisable, even delicate manner, with her shaded nose, her full lips, half open to show a row of fine white teeth, and her single eye – the latter a characteristic of Rivers that made him ‘indisputably’, according to one art critic writing in 1965, ‘America’s leading painter of one-eyed portraits’.1 Superimposed over this portrait, however, are straight lines and stencilled letters in black, dark grey or red that link the features of the face to their anatomical labels in French: ‘cheveux’ (hair), ‘front’ (forehead), ‘sourcil’ (eyebrow), and so on. Their ‘hard edge’ and ‘manufactured look’ are meant to contrast with ‘the softer, indefinite lines’ from the artist’s hand, Rivers explained.2 What appears to be an individual portrait, aiming at the likeness of a specific person, therefore becomes the impersonal illustration of an educational diagram.

The woman depicted is the artist’s young wife, Clarice Rivers (born Clarice Price). The couple had very recently married, in November 1961, and had moved to Paris together. Clarice Rivers was then one of her husband’s favourite models and posed for him on a number of occasions. She was celebrated as one of the most beautiful artist’s muses of the time.3 An undated photograph from the period shows her harmonious, youthful features, her bright eyes and heavy dark hair, which Rivers freely rendered in his portrait (fig.2).

Making the painting

In his 1992 autobiography Rivers gave an account of how his Vocabulary Lesson paintings of the early 1960s came into being in Paris:

I went to L’Alliance Française to learn French. There I found source material for my ‘Vocabulary Lesson’ series, using Clarice as a model. I frequented art supply shops on the Quai d’Orsay. The special racks set aside for amateur artists, with manuals on how to paint the figure, noses, ears, eyes, landscapes and horses, also made for inspiring material.4

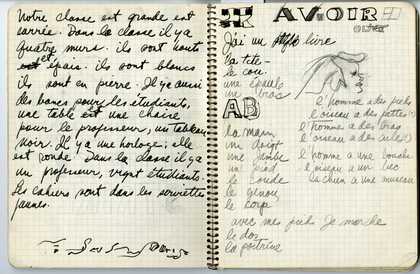

Although Rivers had already lived in France for six months some ten years earlier, his language abilities were quite limited. In his class notebook from his lessons at the Alliance Française, kept in his archives, one can follow Rivers’s painful efforts to acquire basic French vocabulary and grammar (fig.3).

Fig.3

Pages from a notebook used by Larry Rivers during language lessons at the Alliance Française, Paris, 1961

Courtesy the Larry Rivers Foundation

The notebook is full of lists of words and absurd sentences, typical of old-fashioned teaching methods: ‘Les tableaux sont noirs. Les chapeaux sont rouges. Les livres sont bleus’ (‘Boards are black. Hats are red. Books are blue’); ‘Avez-vous deux mains et deux pieds? Est-ce que la petite fille a une tête?’ (‘Do you have two hands and two feet? Does the girl have a head?’). Browsing through the pages, the kind of involuntary black humour that might have inspired Rivers surfaces clearly. In the margins, born from the reveries of a distracted student, even appear the stencilled letters and sketched portraits that would then form the material for Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson.

Fig.4

Slide used by Larry Rivers to enlarge French lesson material for Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson 1961

Slide V III. P3.4., Larry Rivers Papers, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University

Courtesy the Larry Rivers Foundation

Building on the idea of infantilising educational methods, grounded in the learner’s discipline and mimesis rather than his or her intelligence or imagination, Rivers worked with another source material: schematic drawings for amateur artists. As shown in a slide (fig.4), he used an enlarging device to copy a page depicting the features of a schematic face, for which he substituted Clarice Rivers’s portrait in the finished picture. He described it as ‘a lesson book with the face of a rather idiotic-looking boy with lines coming out of the features and a ball at the end of the line with a number on it. The number referred down on the page to the name of the feature.’5

Working in series

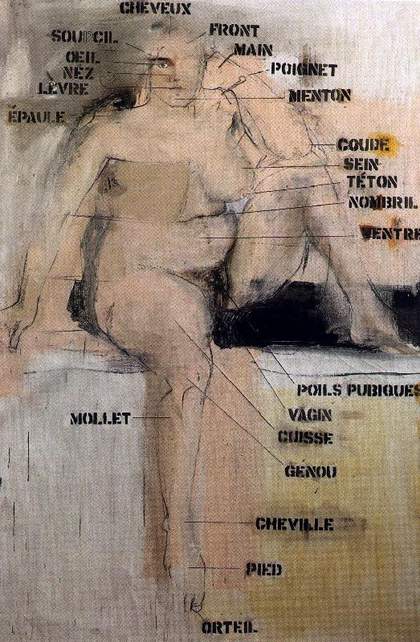

In the early 1960s Rivers enjoyed working in series, producing variations around a common theme. Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson is thus part of a large corpus of such paintings. Other works in the series – which is formally titled Parts of the Body – depict Clarice Rivers’s entire body in the nude, in diverse positions, carefully labelled from forehead to toe, including her most intimate body parts (see, for instance, Parts of the Body – French 1962; fig.5). Some works in the series used different models, including a man. The language also varies: there exist Vocabulary Lessons in English, Italian and Polish, reflecting the travels of Larry and Clarice Rivers during the spring and summer of 1962, from France to the United Kingdom, Italy and Eastern Europe.6 As the artist himself openly admitted: ‘I was able to repeat these subjects without getting tired of them. I look back on them as great years.’7

Fig.5

Larry Rivers

Parts of the Body – French 1962

Private collection

© The estate of Larry Rivers

If Rivers painted Vocabulary Lessons again and again in 1962–5, it was not only because he enjoyed the subject, but also because these paintings were very successful. Elegant yet irreverent, detached but funny, they were widely reproduced in magazines and favoured by amateurs. Parts of the Body I c.1962–5 (private collection), for instance, was bought by the famous pop art collector Robert Scull, and the drawing Parts of the Lower Face c.1962–5 (private collection) was acquired by Harold Rosenberg, the art critic famous for his influential support of American abstract expressionism.8 Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson is one of the most accomplished paintings in the series. It was bought by Tate in May 1962, only a few months after its completion, when Rivers had his first one-man show in the UK at Gimpel Fils in London. This acquisition marked a step in Rivers’s international recognition in the early 1960s.

Approaches to the painting

Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson is a landmark for our understanding not only of what proved to be pivotal years in Rivers’s career, but more broadly of the fundamental mutations of American art in an international context in the early 1960s. Always between categories, Rivers is considered both the heir of the New York School of abstract expressionism and a forerunner of pop art. Trained by the renowned teacher of abstraction Hans Hofmann in the 1940s, he was called ‘the daddy of “Pop Art”’ by Andy Warhol in the early 1960s.9 Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson embodies this transition: Rivers’s painterly, expressive style merges with an incorporation of impersonal, ready-made images. In the second section of this In Focus, ‘An Action Painter Manqué’, Nicholas Martin, the archivist formerly in charge of processing the Larry Rivers Papers at the Fales Library and Special Collections (New York University), addresses these issues through a discussion of Rivers’s early career up until his arrival in France in 1961.10 Martin shows that the artist connected very diverse social, creative and intellectual spaces: his personal and artistic interests as well as his networks made him a free agent, circulating between traditional categories (between abstraction and figuration, between different generations of artists, and between mediums).

Not only does Rivers offer a missing link between two generations of artists, but he also connects two post-war artistic geographies: New York and Paris. Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson is remarkable in this regard. It was realised during Rivers’s stay in Paris in 1961–2, at a crucial moment for his career and his international recognition. The third part of this In Focus will recount Rivers’s connection with French artists (especially the nouveaux réalistes) in the early 1960s, and his new career choices upon arrival in Paris.11 It will emphasise the role of American artists in the Parisian scene, and the importance of Rivers’s friendships and personal ties not only to initiating new artistic collaborations, but also to the achievement of international fame.

Since the 1950s Rivers had been well known in the US for his talents as a portraitist. In Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson his thirst for human representation drifts toward tautology. Words repeat what images already designate; text assigns a merely mimetic function to the visual form. In the fourth section of this study, the philosopher Christopher Penfield discusses this aspect of the painting in relation to a general exploration of tautology by artists in the 1960s, from Jasper Johns to Joseph Kosuth, and in relation to Michel Foucault’s reading of the work of surrealist painter René Magritte.12

Emphasis on the internal logic of tautology should not mean that we forget, however, the impact of external circumstances on an American artist staying in Paris at the end of the war in Algeria (1954–62). The final section of this In Focus explores the political climate of early 1960s France and argues that despite their apparent (and claimed) neutrality, Rivers’s series of paintings from 1961–2 are penetrated by their context of violent decolonisation struggle and cold war politics.13