The Statue of Liberty stands at the centre of Static 2009 (Tate T13425). McQueen’s camera remains fixated on the monument throughout the looped film, never losing focus on the colossal figure despite the constant movement of the helicopter. In doing so, Static functions as a form of portraiture, a brief but intense examination of Lady Liberty, and an interrogation of her identity and meanings.

Scale and significance of the statue

Since its unveiling on 26 October 1886 the Statue of Liberty has stood dramatically on Liberty Island off the coast of New York, and has become one of the most iconic sights in the world. Measuring 92.99 metres from the ground to the top of the torch, with the figure itself measuring 46.05 metres in height, Liberty dominates her watery surroundings.1 Her upright draped form, dominant outstretched arm and striking pointed crown create a strong and stylised image, easily recognisable and reproducible. Designed by the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and created in Paris by the Gaget, Cauthier et Cie workshops in 1884, the Statue of Liberty was shipped in 1885 to New York where it was presented as a gift to the United States from the people of France.2 Bartholdi developed his plans for Liberty (originally titled ‘La Liberté éclairant le monde’, or ‘Liberty Enlightening the World’) at the start of the well-documented French Third Republic’s period of ‘statuemania’.3 A similar embrace of public statues erupted in America at the same time: historian Erika Doss has argued that from the 1870s to the 1920s, following the American Civil War, ‘statues not only embellished the postbellum public landscape, but also encouraged passionate and consensual understandings of nationhood’.4 According to art historians Robert S. Nelson and Margaret Olin, this is in part the ability of the monument to ‘express the power and sense of the society that gives it meaning, and at the same time obscures competing claims for authority and meaning’.5 In the period of ‘statuemania’, the capability of monuments to rewrite or even erase history as much as commemorate it, came to the fore.

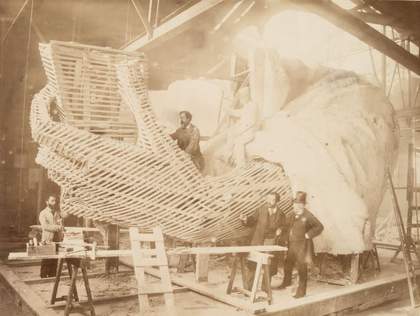

Fig.1

Construction of the skeleton and plaster surface of the left arm and hand of the Statue of Liberty, 1883

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs

Photography Collection, New York Public Library

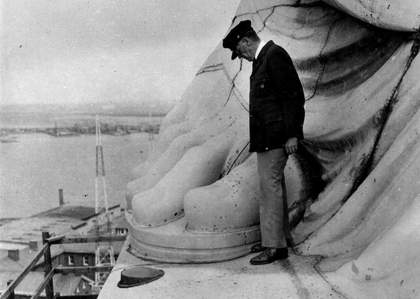

According to Nelson and Olin, ‘The period after the French Revolution … saw the formulation of concepts crucial to the notion of the historical monument and its preservation. Because social turmoil breaks continuity with tradition and the immediate past, new monuments can represent an uncontested version of the past’.6 The scale of the Statue of Liberty reinforces something of this desire to shape both past and present through monumentalising particular values. Early photographs of Liberty’s construction demonstrate the extent of the statue’s giganticism: men stand dwarfed by her fingers while creating the hand holding the tablet, while another is nestled within her thumb (fig.1). Another image, this time from the 1930s, demonstrates the surreal disjuncture in scale between visitor and statue, as a man stands next to Liberty’s enormous foot, her toes reaching almost to his waist (fig.2). Liberty’s scale, supported by French engineer Gustave Eiffel’s innovative inner structure for the statue, is reflective of her creator’s ambitions, and perhaps of the strength of feeling behind the political will to link France and America through the visible establishment of shared ideals.

Fig.2

Superintendant at the foot of the Statue of Liberty, c.1930s

Courtesy National Park Service

Yet the statue’s scale is also perhaps reflective of less bombastic, politicised and even conscious intentions. Art historian Benjamin Buchloh has argued in relation to more recent sculpture that enormous public monuments are indicative of a time of insecurity and uncertainty, as if they are attempts to cement a view of history and the present when it is at its most watery and weak. The ‘stability and weight’ of colossal structures offer ‘balance’ to such insecurity and fill the ‘gaps of historic identity’.7 Such large-scale sculptures epitomise the impulse to, in historian Eduardo Cadava’s words, ‘reread and rewrite history’ during the caesura or ‘blink’ of traumatic periods.8 Indeed, Cadava argues that while Karl Marx viewed revolutions as ‘the locomotives of history’, for Walter Benjamin they represented the ‘reach for the emergency brake’.9 The statuemania of France, and to a lesser extent of America, at the time of Liberty’s creation certainly suggests a desire to populate a recent power vacuum with figures representing contemporary ideals. Liberty, alongside equality and fraternity – the three values that constitute the French national motto – could be solidified, stilled and enlarged to fill any such ‘gap’.

In both France and America the political landscape nurtured Liberty as a particularly popular subject, despite the ongoing contested meanings of the word, and the irony of embodying liberty within a female form at a time when women were disenfranchised. As art historian Marvin Trachtenberg has suggested, by the time Bartholdi created his sculpture, understandings of liberty as an embodied concept had changed from the early Roman goddess and a literal freedom from slavery (abolished officially in America after 1865) to ‘a much broader, more diffuse concept, involving liberties of many kinds, centring on the freedom of citizens from undue constraints on their life by legitimate rulers, or on their body politic by alien forces’.10 Bartholdi took on the challenge of creating a statue to encapsulate such freedoms, and in the process created a strangely static vision of liberty.

Fig.3

Eugène Delacroix

Liberty Leading the People 1830

Oil paint on canvas

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Trachtenberg has noted the significant influence of Eugène Delacroix’s depiction of Liberty as a striding, earth-bound goddess of the people in his 1830 painting Liberty Leading the People (fig.3), as well as Bartholdi’s diversion from this passionate, semi-naked warrior to the more stationary, fully-clothed and peaceable figure for his statue.11 While Delacroix’s Liberty is depicted on the move, with one heel raised off the ground, Bartholdi’s stands straight with newly unchained feet. Rather than clutching a rifle, brandishing a flag and striding forward over the corpses of battle, with the wind rushing against her and her head turned towards the revolutionaries she leads, Bartholdi’s Liberty is decidedly more static and demure, boldly holding aloft a torch to ‘enlighten the world’ in one hand, and clutching a tablet engraved with the date of the American Declaration of Independence, ‘July IV MDCCLXXVI’, in the other. Her calm stern face, which Bartholdi said was modelled on his mother, appears both stylised and hard, staring implacably ahead with blank eyes and a determined gaze. This is a Liberty who is designed to be static both literally and philosophically: an immovable statue and an immutable concept.

Indeed, McQueen’s circling of the statue in Static, and the title of the artwork itself, reflect a broader debate about the nature of statues and public sculpture during the period in which the Statue of Liberty was made. In Paris, it was not until Auguste Rodin’s radical rejection of a plinth for his Burghers of Calais 1884–95, and his desire for ‘a dramatisation from all sides’, that creators of statues began to envisage a work that could be viewed from all angles by a potentially roaming viewer, rather than having a definite ‘front’ from which the viewer should stand and admire.12 In the case of the Statue of Liberty, this question of direction became politically loaded. The fact that she faces the open ocean, with her back to America has led Trachtenberg to argue that Liberty was not just ‘an exile or expatriate; she was also an emissary’, and could be seen as part of a French tendency to ‘project herself abroad’.13 He suggests that this question of the direction of Liberty’s gaze was part of the reason for initial hostility towards the statue by some Americans, until Emma Lazarus’s famous poem ‘The New Colossus’ (1883), which is engraved on a tablet held within the statue’s pedestal, reinterpreted Liberty’s stance ‘not as away from America, but as America itself welcoming the new arrival’.14 Lazarus’s poem famously describes Liberty as ‘Mother of Exiles’, and suggests that this ‘mighty woman’ offers maternal respite and nurture to those who have been spurned by their own countries:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

‘Keep ancient lands, your storied pomp!’ cries she

With silent lips. ‘Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!’15

What is notable here is that it is the position of the viewer, both physically and socio-economically, which has moved. In Lazarus’s poem, it is not the case that Americans stare at the back of the statue, but rather that the statue represents them staring out, and it is non-Americans, in a ‘wretched’, and ‘yearning’ state, arriving at the start of their American dream, who hold the position of Bartholdi’s intended viewer. In both Bartholdi’s vision and Lazarus’s poem, these pre-defined ‘huddled masses’ move towards the statue on a pre-defined route and are greeted by the particular side of Liberty which is chosen to project outwards.

What McQueen’s circling enables, then, is a freedom for both himself and the viewer of his film that suggests a more privileged position than either the American inhabitant or incoming migrant. McQueen’s camera never stops, but rather presents a determined and unrelenting examination of Liberty from all sides. As curator Lizzie Carey-Thomas has argued, this continuously rotating camera highlights the ‘worn, weather-beaten patina of [Liberty’s] surfaces, and she becomes, once again, an object’.16 McQueen’s film highlights the power imbalance between stasis and the freedom of movement. As an empowered viewer able to navigate around the statue by helicopter, and to zoom up close to it through the camera, McQueen becomes the embodiment of liberty, while the statue itself reverts from iconic symbol to physical object, from universal concept of freedom to a mass of weathering copper. Like a hunter encircling its prey, or an ethnographer examining a specimen, McQueen supersedes the position of welcoming mother or exiled migrant; on behalf of his own freely roaming viewer he escapes Bartholdi’s projected position and surveys the colossal monument at its own eye level. In doing so his artwork suggests that fixity of any kind, including enforced movement, is a form of imprisonment.

Fig.4

Steve McQueen

Deadpan 1997

Film, 16 mm, transferred to video

© Steve McQueen

Liberty, and the lack thereof, are longstanding concerns within McQueen’s work. His feature films have shown this most directly, with depictions of physical imprisonment in Hunger (2008) and 12 Years a Slave (2013) and the entrapment of addiction in Shame (2011). His artwork too has demonstrated a persistent interest in ideas of freedom, movement and power relationships. Exodus 1992 is a brief and spontaneous film following two men weaving through crowded London streets, each holding a coconut palm that sways, almost torch-like, above their heads. At last the men climb aboard a red London bus and escape the camera, with McQueen’s title suggesting a biblical resonance with the Israelites’ exodus to the Promised Land. In Static, the camera is constantly moving and highlights the freedom and power of the artist as he chooses to remain fixed on his subject. When both camera and protagonist are static, as in Deadpan 1997 (fig.4), it is the surroundings which move, perilously, comically, repeatedly: the wall of the building falls over the head of the unflinching artist, who emerges time and again through the window, which moves from vertical to horizontal, from wall to floor. The image of McQueen here, like that of Liberty in Static, is one of defiant resilience as well as enforced stillness. The Statue of Liberty is thus presented in Static as an oxymoron or contradiction in terms, since to be stationary within McQueen’s work is necessarily to be restricted, to lack freedom. That the statue has long held a mythical status as the ‘Mother of Exiles’, of those who face the equal unfreedom of being forced to move, is an irony highlighted within McQueen’s film.

Approaching Liberty: The statue in recent visual culture

That the Statue of Liberty functions as a monument, and a means of remembering, remains certain, no matter how mobile are the meanings it codifies. For Bartholdi, his inspirational lecturer Edouard René de Laboulaye, and even then-President Grover Cleveland, Liberty was a republican vision of democracy, a light piercing ‘the darkness of ignorance and man’s oppression’.17 However, in keeping with the hybrid nature of monuments discussed above, the statue’s meaning has remained neither static nor singular. Writing in 1976, Trachtenberg noted the many different ways in which the statue had been referenced, appropriated and re-imagined, and argued that while Liberty lives on as Lazarus’s ‘Mother of Exiles’, the statue went on to stand more broadly as an image of America.18 Indeed, the iconic image of the statue has been used to signify human civilisation per se, particularly in Hollywood disaster movies in which her destruction provides a visual shorthand for the threatened end of the world. The most famous example of Hollywood’s use of the statue in this way is perhaps the closing scene of Planet of the Apes (1967), in which the protagonists’ surprise encounter with the half-buried statue prompts a chilling reassessment of both geographical location and historical events: the submerged Liberty stands as the cartographical marker of human degradation. Popular culture has also used the statue as a symbol of entrance to a new world in films ranging from Charlie Chaplin’s The Immigrant (1917) to Titanic (1997), where Liberty functions as a symbol of survival and safety. As monument, the Statue of Liberty serves both as a memorial to a history of migration and national development, and as a short-hand signifier for Western confidence worldwide.

Artists have similarly drawn upon the visual dynamism of the iconic statue, although often with a more interrogatory approach towards her symbolic nature. Pop artists were particularly interested in Liberty: she was an obvious target for Claes Oldenburg’s work on anti-monuments. Oldenburg presented his Proposed Colossal Monument – Fan in Place of the Statue of Liberty in 1967, two years after his Proposed Underground Memorial and Tomb for President John F. Kennedy 1965, which suggested creating a statue of the president at the same scale as the Statue of Liberty, but then positioning it upside down in the ground. These drawn ‘proposals’ highlight Oldenburg’s interest in the everyday and the mundane over and above the grand and symbolic. His other proposals to replace the Washington Memorial with a pair of enormous scissors, and Nelson’s Column in London’s Trafalgar Square with a giant gear stick demonstrate a similar interest in mute, common objects over the material embodiment of ideals or heroes. Meanwhile, the decision to focus his ironic attack on the Statue of Liberty reveals its special status as one of the most famous and significant monuments in the world by the 1960s.

American artists Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg also incorporated the statue into their artwork. Both Rauschenberg and Warhol used postcards of the statue as a marker of her magnetism for tourists and the mass production of her image within popular culture. While Warhol’s use of the statue in the 1980s saw him treating Liberty as a famous female celebrity, with repeated stylised prints of her face drenched in vivid colours just as he did Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy, in 1962 Warhol produced a more sombre depiction of the statue, which has been interpreted as marking the start of his Death and Disaster series of silkscreen paintings.19 In a 2012 catalogue entry for the artwork, the auction house Christie’s argued that Warhol recognised a ‘dark side’ to the statue’s nature as a symbol of hope, with immigrants offered no guarantee of a right to remain. Indeed, Ellis Island became a site of despair and sometimes suicide.20 Warhol’s Statue of Liberty, made at a time of political unrest during the Vietnam War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and demand for cultural change through the civil rights, feminist and gay rights movements, presented an interrogation of the statue that was reflective of a broader reassessment of American identity and values. The repeated image of Liberty is presented in both red and green, creating an ‘optical’ artwork which could appear three-dimensional when viewed with special glasses. Yet this doubling of each image also presents a fuzzy, blurry, de-stabilised vision of the statue. As with McQueen’s Static, Warhol seems keen to emphasise the solid, physical reality of the statue while also making it appear vulnerable to shifts and movement. Indeed, curator Heiner Bastion has suggested that Warhol’s Statue of Liberty presents a ‘tautological procession of motifs’ which seem like ‘clips from a movie’, while the ‘grid of reproduction conveys instability and strangeness’.21 Warhol’s and McQueen’s artworks visualise the impulse to see – and the difficulties of seeing – the Statue of Liberty clearly. Both artists can also be credited with attempting to reappraise its symbolism during periods of renewed pressure on the ideal of freedom both nationally and internationally.

If, as argued above, the monument occupies a hybrid space between stasis and motion, object and subject, death and life, then its constant change connects it forever to the evolving present. Nelson and Olin note this contemporaneous quality of the monument and its dependency upon an ‘actual, present-oriented network of relationships’.22 Most recently, the Statue of Liberty has become a renewed symbol of freedom in the face of terrorism: President Barack Obama’s reopening of the statue to visitors who wanted to climb to its crown in 2009, the year that McQueen made Static, symbolised people’s reclamation of their freedom to inhabit Liberty both physically and metaphorically after the attacks on New York on 11 September 2001. These associations were furthered after the terrorist atrocities in Paris in November 2015 when the Statue of Liberty again became a symbol of the alliance between America and France and their shared pursuit of freedom. Indeed, Static’s scrutiny of a statue symbolising a Western welcome to migrants has also gained renewed urgency and poignancy in the wake of the migration crisis that escalated in 2015. McQueen’s determination ‘not to let the dust settle’, and his use of the past to highlight the concerns of the present are reflected in the changing significations of his own artwork.23 As has been argued above, Static functions itself as a monument, and as such, its connotations alter and develop over time along with those of the statue it encircles.

Fig.5

Danh Vō

We The People 2010–14 (installation shot)

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel

Photo: Nils Klinger

Fig.6

Danh Vō

We The People 2010–14 (installation shot)

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel

Photo: Nils Klinger

Aside from Static, the most significant contemporary artwork to address the Statue of Liberty is Danh Vo’s We The People 2010–14 (figs.5–6), the title of which uses the first three words from the American Constitution of 1787. Vo’s project saw him construct life-size copper replica fragments of the Statue of Liberty, which he has exhibited around the world. The rippled, truncated extracts of Liberty’s surface litter the gallery with truncated shards of flowing garment, or smooth angled surface. Only some fragments are identifiable: disembodied fingers, a couple of ringlets of stylised hair, or the front section of a foot take on a more ominous character, reflecting the dismemberment of Liberty in Hollywood blockbusters. We The People highlights the literal thinness of Liberty’s surface: the artist conceived of the project after discovering that the statue’s hammered copper surface measures only 2.5 mm in depth. His use of 1:1 scale highlights the contrast between Liberty’s vast scale and her apparent physical fragility, emphasising in turn her hollow core.24 For the artist, who left his native Vietnam in 1979 on a boat in search of the United States but settled instead in Denmark, the fact that the Statue of Liberty can travel across the world through his artwork is significant: ‘Let her travel, let her be spread around. Let it just be this fluid mass that travels and becomes something very different’.25

Danh Vo’s artwork shares with McQueen’s Static a similar desire to make the Statue of Liberty move. For We The People, Vo suggests that Liberty should travel to see others: the right to glimpse freedom should be available all over the world, even if this involves seeing it in fragmented form. His statement above suggests that the Statue of Liberty itself should become the shifting, watery mass that historically has carried people towards her by boat. The curtailing action of the title, itself an extract, also implies a more global and universal claim on the concept of freedom than the whole American Constitution, or the complete, static statue in New York, would suggest. In this respect McQueen and Vo have used Liberty to question the stasis and reach of her monumental symbolism.

The statue and the screen

Both McQueen and Vo’s projects suggest that part of a monument’s adherence to contemporaneity is connected to the changing ways in which people view it. While historically welcoming migrants arriving by boat, Liberty is now more commonly visited by tourists wanting to photograph and climb its iconic structure. Olin and Nelson note the mutually supportive relationship that exists between monuments, the organisations such as UNESCO that sanction them, and global tourism.26 However, while historically monuments have drawn people to see them in person, increasingly technology allows a viewing relationship through the screen, which does not require movement on the part of the viewer but which presents an endlessly moving landscape, a condition replicated by McQueen in Static. The cityscape of New York judders behind the Statue of Liberty throughout the artwork, distanced but present, and never still. Historian Mitchell Schwarzer has explored the way in which technology is altering the perception of both monuments and the past in general, and argues that ‘the moving landscape’, as he defines our technologically saturated condition, has radically reconfigured the relationship between landscape and monument:

In the moving landscape, monuments are no longer just exceptional places or artworks: the sphere jutting out of the centre of a space, the secluded garden of antique desire. Nor are monuments subsumed into the scale of geography, their size translated into bridges, big boxes, or boundary lines, their sanctity lost in a sea of individual acts and purchases. The monument makes a surprising comeback in the moving landscape. Despite the entropy of television, the Internet, and global transit networks, the great artistic monuments of the past are now getting a new lease of life. Through flickering glass, they live again and again in the throes of tourism and entertainment. As a result, artistic monuments share viewing time with natural monuments, popular monuments, underground monuments, the monuments of spectacle, sex and violence. In the moving landscape, the exceptional broadens to geographic scope and the word monument takes on the historical scope of technology.27

This reconfiguration is explored by Schwarzer through reference to philosopher Paul Virilio’s theory articulating the losses of accelerationism, the chief of which is a confusion over past and present. Schwarzer defines ‘the moving landscape’ as prevalent and produced, a ‘supersonic digitised travel’ riddled with the rules of marketing, and offering up the past so quickly, frequently and easily that ‘it is no longer historical’ and incapable of fully impacting upon the present.28 Schwarzer shares some of Virilio’s melancholic tone in his diagnosis of an increasingly flat historical plane.

Such upsetting of the conventional relationship between past and present necessarily affects both monuments and memory, so that while ‘traditional memory’ worked against loss, in Schwarzer’s account, ‘Technological memory, by contrast [to traditional memory], is all about gain, bathing us in the noisiness of recovery and reproduction’. There is some resonance here with Static, perhaps most overtly through the title of the artwork. While Static clearly relates to the stationary nature of the Statue of Liberty and draws attention ironically to the constantly moving camera, the title also functions as a description of visual noise on television and video. That noise is usually considered a flaw of the medium, an interruption to the intended broadcast or a result of a blank, unused video. While there is no visual noise evident within the artwork, the sound of the helicopter engine functions as an analogue to the constant illegible whirr of electronic static. For Schwarzer, the ‘noisiness of recovery and reproduction’ is the price of technological memory, as though the working of calling up the past on screen produces a similar distracting buzz.

In Schwarzer’s account the effects of this condition prompt a stark warning, as ‘we have moulded much of history and geography into a continuous field of visual artifice with enormous transformative capabilities, and we are becoming our own recreations’.29 The moving landscape in Schwarzer’s argument then ultimately produces stasis:

In its constant penetrations of a fanning periphery, the moving landscape makes irrelevant prior temporal dualisms of possession and loss, remembering and forgetting. And paradoxically, because velocity has no vanishing point, the experience of the constantly moving landscape can seem downright motionless.30

As argued above, in McQueen’s work to be motionless is often equivalent to being imprisoned; to be static is to lack liberty. Schwarzer’s text at times takes on the melancholic tone of Virilio’s, and his conclusion rings with warning. Constant motion creates similar conditions to complete stasis, disabling monuments in the moving landscape and stripping them of their ability to tell of the past or be reconfigured by the present. The ‘noisiness’ of technological memory, recovering and recreating, produces little but a blank, akin to video static. McQueen’s film presents a similar nexus of monument, memory, literally moving landscape and current technology as Schwarzer’s discussion, and McQueen’s artwork also carries a sense of threat through the loud fixation of the helicopter on the statue.

However, if Static too offers a form of warning, it is different in nature to Schwarzer’s concerns. McQueen’s film does not allow the viewer any respite from constant movement; New York appears to shift and spin around as the helicopter’s whirring and circling seem to build throughout the work. There are immediate connections with the sense of menace from the air that in 2009 was fresh in the memory of those who had either experienced or witnessed the attacks of 2001. But there are also other connotations of video static – of the ability to be erased, to be made blank – which warn against the very invisibility against which monuments, and McQueen’s work as a whole, try to fight. Static warns against a lack of content, a hollow blankness which becomes almost sinister in the cold copper eyes of the Statue of Liberty. The circling motion of the film echoes the emptiness of the circle as a zero, a sign of nothingness, the constantly pulsing circle of buffering screens and digital pause.

There are echoes here with McQueen’s depiction of New York in Shame (2011), a feature film whose protagonists’ encasement within the smooth glass surfaces of apartments, offices, hotels and elevators mirrors the enslavement of the central character, Brandon, to the laptop screen as a result of sex addiction. The city is also presented as a place of great magnetism, with McQueen lingering on Brandon’s sister’s rendition of ‘New York, New York’, and making pointed references to her and Brandon’s own migration to the city. Indeed, at his lowest point in the film, Brandon runs outside to the waterfront and sinks to his knees in desperation. His view here – which the audience is not shown – is finally static and unmediated by a screen or window frame. Shame presents twenty-first-century New York as a compartmentalised environment, divided by surfaces as thin as the Statue of Liberty’s copper sheeting, and easily made empty through its enabling of addictive and distanced relationships. McQueen’s presentation of New York in Shame and his use of video in Static emphasise a very modern experience of the Statue of Liberty, highlighting the moving landscape and the hollow imprisonment of apparent but mediated freedom.

Ultimately Static warns of the perils of allowing familiar landscapes and monuments to become empty through lack of attention and interrogation, or indeed of constructing them while blinking in front of the continuum of history. All that should remain constant, McQueen suggests, is the commitment to look, and the desire to see. For Schwarzer, ‘the frenetic transformations of capital, technology and fashion construct an almost instantaneous obsolescence for any present object or event’.31 In flight, McQueen’s camera lifts its stare to return that of Liberty’s, and, in a straightforward, understated manner, highlights and fights her blankness and her inability to see. By doing so, he implies both the complexity and the urgency of Liberty’s endurance in the present.