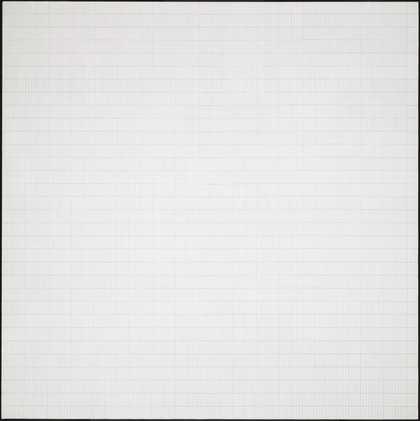

Fig.1

Jennifer Bartlett

Surface Substitution on 36 Plates 1972

Tate T06637

Painting was up for radical revision by the mid-1960s. The traditional distinction between painting and sculpture seemed irrelevant to artists interested in pushing the phenomenological and material specificity of their work. As the artist Donald Judd wrote in 1965, ‘Half or more of the best new work in the last few years has been neither painting nor sculpture. Usually it has been related, closely or distantly, to one or the other.’1 Judd, along with others including Sol LeWitt, painted his three-dimensional structures using commercial lacquers and enamels. In 1965 critic Lucy Lippard identified a ‘third stream tendency’ in art, involving shaped canvases and painted structures, with artists employing commercial materials to address ‘the assault of commercialism on the American eye’.2

When Bartlett adopted a new method of applying commercial enamel paint onto enamelled steel plates in 1968, one which she would later employ in Surface Substitution on 36 Plates 1972 (Tate T06637; fig.1), her materials and confined ‘dotting’ process were a distinctive and personal variation on ideas that were circulating as she sought to establish herself in the New York art world. Artists associated with minimalism frequently used standardised modules and industrial fabrication (for instance, the lead, zinc, magnesium or steel tiles of Carl Andre’s floor pieces, such as his 144 Magnesium Square 1969; fig.2), seeking to remove the hand of the artist and align their practice with industrial production. Curator Kynaston McShine articulated minimalism’s outlook on the occasion of his landmark exhibition Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors, held at the Jewish Museum, New York, in 1966. ‘Methods of industrial fabrication in the Space Age have facilitated the accuracy of many of the structurists’, McShine wrote in the catalogue introduction, referring to a group of artists who would become associated with minimalism.3 Industrial materials and anonymity of execution were properties embraced by the ‘Space Age’ artist who could now ‘conceive his work, and entrust its execution to a manufacturer whose precision and skill convey the standardized “impersonality” that the artist may seek’. This ‘impersonality’ was, in McShine’s estimation, a stance ‘against the open welded sculpture of the fifties, with its emotionalism, improvisation, and emphatic marks of individual sensibility’.4

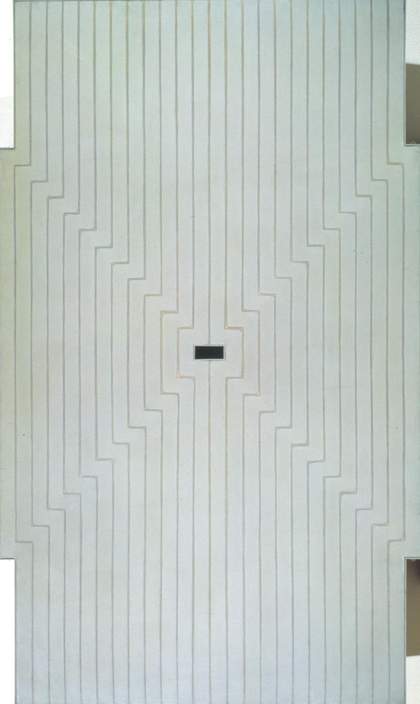

Fig.4

Frank Stella

Six Mile Bottom 1960

Tate T01552

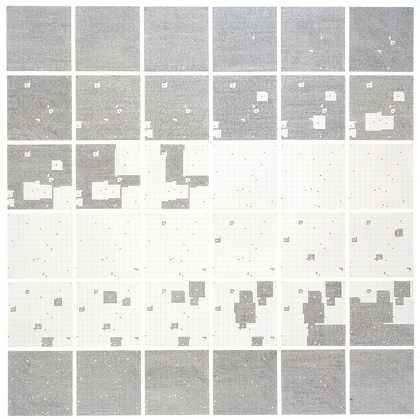

System-based approaches to painting were likewise embraced in reaction to the subjectivity of the ‘Tenth Street touch’, as the gestural style of abstract expressionism associated with Willem de Kooning was dubbed by the formalist critic Clement Greenberg.5 Bartlett’s dotted plates emerged as part of a broad movement among ambitious young painters to reconfigure painting for a new era. Painting had an important role within minimalism: in Agnes Martin’s hand-drawn grids set against atmospheric fields of blue, cream and grey (fig.3); Jo Baer’s white acrylic canvases, with internal frames of black and dark green; Frank Stella’s striped paintings in which the internal forms repeat the contours of the edges (fig.4); and Robert Ryman’s articulation of the support, which by the late 1960s included steel plates. All were prominent painters who exhibited their work alongside the fabricated sculptural objects associated with minimalism. To let go of the canvas, as Bartlett did, was exactly in line with more radical contemporary directions in painting, as was her concern with employing a system such as the Fibonacci series in Surface Substitution to generate the terms of a painting.

Systemic painting

In 1966 the exhibition Systemic Painting, curated by Lawrence Alloway and held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, presented a set of new attitudes toward the medium. The show included the major painters associated with minimalism – Martin, Stella, Baer and Ryman, along with Ellsworth Kelly and Kenneth Noland, both of whom had become prominent in the 1950s in association with hard-edge painting or ‘post-painterly abstraction’, a term coined by Greenberg.6 Al Held, one of Bartlett’s painting instructors at Yale, was included the show, as was Bartlett’s friend Robert Mangold.7 Systemic Painting articulated a new approach to painting, one in which the module and the grid functioned as ‘the visible skin’ rather than invisible organising principles of a painting.8 Alloway wrote that a painting’s organisation, through grid and system, was not ‘an underlying composition, but a factual display. In all these works, the end-state of the painting is known prior to the completion’, allowing that ‘This does not exclude empirical modifications of a work in progress, but it does focus them within a system. A system is an organized whole, the parts of which demonstrate some regularities.’9

Systemic Painting attempted to redefine painting for a new age in which many artists were preoccupied with the implications of systems – whether computational, physical, economic or social. An influential essay written by the artist and critic Jack Burnham in 1968 articulated the relevance to art of systems analysis and theory. Rather than autonomous objects, works by artists like Hans Haacke were regarded as responsive physical systems: Haacke’s so-called ‘weather boxes’, such as Condensation Cube 1963–5 (Tate T13214), and patches of grass grown in a gallery (Grass Grows 1967–9), were microcosms that responded to specific ecosystems. Even Andre’s floor pieces were characterised by Burnham as ‘architectural modifications’ in which ‘each metal grid’s thermal conductivity was registered through the soles of one’s feet’.10 According to Burnham, ‘The priorities of the present age revolve around problems of organization’.11 Systems had ‘esthetics’, he noted, and were being newly visualised, rather than remaining abstract forces shaping social and economic realities, from capitalism to the Vietnam War (1955–75).

Organised using the grid format and the Fibonacci series, and systematically addressing the medium of painting, Surface Substitution is an instance of systemic painting. Through Bartlett’s commercial materials and rote dotting technique, Surface Substitution further points to systems of commodity production and consumerism that sit in tension with the human presence implied by the hand of the artist. The work perhaps also refers to the binary codes of information technology; in 1972 the artist and musician Laurie Anderson referred to the painted enamel dots of Bartlett’s plates as ‘the primary informational “bit”’.12 Giving systems a visible and legible expression acknowledged the complex interconnections of the contemporary world, and such transparency was an implicitly political expression, setting itself in opposition to opacity and invisibility, obfuscation and hidden meanings.

Coded imagery

The works in Bartlett’s first New York gallery exhibition, held at the Reese Palley Gallery in early 1972, included plate pieces with recognisable imagery – maps and houses – along with others containing dots placed according to mathematical formulae. The latter were similar to Surface Substitution, a work which, although not included in the show, was executed around the time of this exhibition. Bartlett’s technique of painting coloured enamel dots on steel plates provided consistency, even as her work rejected a clear pictorial theme and refused to privilege either representative or abstract imagery. The show yielded the first reviews of Bartlett’s plate pieces, and ideas of coding and information systems prevailed in their reception as critics reached to connect the different types of imagery. Critic Carter Ratcliff understood her coloured dots as systems or signs in which colour was not descriptive, but an organising principle:

She uses colours for the most part as signs, as abstract differentiations in illustrating the Fibonacci series, ‘digital expansion of random numbers’, ‘variations on a series of random numbers’, and so on. She doesn’t analyze these subjects; rather, she provides a quick glance at each one of them. Color is used less abstractly, but still not as color, in a series showing a house reduced to a pattern of dots and then put through the seasonal variations.13

As mentioned above, Laurie Anderson’s review of the Reese Palley show described Bartlett’s ‘coded’ imagery as follows: ‘A painted enamel dot (the primary informational “bit”) and the square format were the given coefficients in a series of permutations’.14 She went on to note that the rigours and logic of the ‘binary systems, descriptions of parabolas and mathematical combinations’ could be at odds with their visual form, ‘which can seem prosaic beside it’.15 The mathematical works made intellectual sense, but to Anderson, were ‘marginally logical visually’. How did the systems on which Bartlett’s works were based contribute to the significance of the work itself? This conflictual relationship between ‘subject’ (house, map or Fibonacci series) and ‘content’ (substance of the work as a whole) is a riddle that animates Bartlett’s plates.

Anderson also noted in her review ‘several series of intersections and several of forms that seem to compress, dissolve, and regroup as if they were frames cut from a film about atomic interaction’. Surface Substitution might also be described as involving such compression and dissolution, which suggested to Anderson a kind of abstract energy, one with the apocalyptic association of a nuclear reaction. On the other hand, the plates also reminded Anderson of ‘samplers that were – from plate to plate – coming unstitched’, in reference to small panels of embroidery. The latter is decidedly domestic, casting Bartlett’s labour in terms of the confined, rote actions of women’s work, the painted dots as stitches.16 Within the same review, then, Bartlett’s restrictive dotting process drew very different kinds of mass cultural associations, contributing to the enigmatic nature of its meaning.

Such associations implied the importance of distinct processes, meanings and systems at a dynamic historical moment, as computational thought became prevalent and the socio-political role of women evolved rapidly in American culture. For Bartlett and other artists of her generation, process itself came to hold significance, registering the artist’s hand and her presence: her physical and individual crafting of the work through hand-painted dots, with this repetitive dotting alluding dually to the mechanistic and the domestic. Although Bartlett outsourced the fabrication of her plates, it was important to her to ‘dot’ her plates herself, while the repetitive process freed her from concerns about style and eliminated decision-making once a schema for the pieces was established.17 This process, in which the mechanical was emulated by hand, acknowledged contradictory forms of labour – automated repetition combined with hand-stitching, for instance – that foregrounded the tensions between spontaneity and the systematic. As is shown elsewhere in this In Focus, the idea of process itself as the subject of the work was central to Surface Substitution, in which duration and repetition and took on an aesthetic as well as a conceptual value in Bartlett’s approach to art-making.18