The French revolutionary leader Napoleon Bonaparte once stated that in order to understand a person, it is important to know what was happening in the world when they were twenty years of age.1 When Winifred Knights entered and won the 1920 Rome Prize at the age of just twenty-one with her painting The Deluge (Tate T05532; fig.1), her depiction of the biblical story of Noah’s ark and the flood, there was a great deal going on in her world that – consciously or unconsciously – would have served to influence her interpretation. Europe had just emerged from the First World War, the events of which had resulted in considerable personal trauma for Knights, as well as national grief and upheaval. But in addition, and partly in response to the war, there were significant shifts taking place in theological thought at that time that would continue to play out throughout the twentieth century. While nineteenth-century theology had been tinged with a prevailing optimism about the progress of humanity, the First World War and the interwar years led to more sobering reflections on human virtue and various theological assumptions were re-examined, such as the conflation of national identity with the Kingdom of God, and – perhaps more significantly – where and how God is present in human suffering. Looking at Knights’s The Deluge through the lens of the social and theological mood of the 1920s, this essay will show that, in subtle ways, her painting brings into focus some of these changing ideas.

Fig.1

Winifred Knights

The Deluge 1920

Tate T05532

The First World War and biblical apocalyptic

The choice of the biblical flood as the set subject matter for the Rome Prize of 1920 is not insignificant, for it was common among artists, poets and writers to use the most disturbing of the biblical narratives as a frame for their reflections on the First World War.2 One example is Wilfred Owen (1893–1918), the Welsh war poet who grew up in a devout Christian family where he learned the conventional pattern of biblical interpretation: that no matter what struggle and suffering might intervene, the narrative always led, ultimately, to the promise of redemption. But after the utter futility of his war experience Owen retold these stories in his poetry, recasting them as tales of hopelessness rather than redemption.

In ‘Greater Love’ (1917–18), for instance, Owen took quotes from and made allusions to the passion narrative in St John’s gospel and compared Christ’s death to the many young lives sacrificed in war, reflecting on the seeming absence of God in such desperate times. Owen’s ‘The Parable of the Old Man and the Young’ (1918) turned the biblical sacrifice of Isaac from a story of salvation to one of wilful destruction. Placing the account from Genesis 22 into the scenes of conflict in northern France, Owen describes a young man, bound and laid upon an altar of ‘parapets and trenches’, and in an almost direct quote from the King James Authorised Version of the Bible, delivers the Angel’s words of hope and rescue: ‘Lay not thy hand upon the lad’. Yet whereas the biblical narrative ends in an eleventh-hour reprieve both for Abraham and his son, Owen subverted the story to voice his horrified objection to the futility of war, and the failure – as he saw it – of the ‘patriarchs’ of war to bring it to a timely close, at such terrible human cost:

When lo! an angel called him out of heaven,

Saying, Lay not thy hand upon the lad,

Neither do anything to him. Behold,

A ram, caught in a thicket by its horns;

Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him.But the old man would not so, but slew his son,

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.3

The story of Noah’s flood similarly proved an apt image for artists to reflect on the First World War, with its capacity for addressing issues of guilt and innocence, justice and redemption, and the presence or absence of God in the midst of apocalyptic horror. The flood already had a long history of artistic representation, with the focus variously placed on these different aspects of the story. What makes Knights’s representation so interesting is that her interpretation of the story belongs precisely to its time. Just as Owen’s poetry used biblical narratives to address questions about the morality of the war, so Knights’s painting seems to express not only the depth of human suffering and trauma, but the anxiety experienced in the upheaval of the social and political landscape.

When film producer Scott Franklin stated in 2013 that the Genesis flood story ‘is a very short section of the Bible with a lot of gaps’,4 he neatly summed up the fact that the biblical story is open to multiple interpretations, and that the narrative retained in the popular imagination is only an approximation of what is actually found in the text. Not only are there gaps in the story, but there are also points where the narrative seems to double back and repeat itself with new information. Furthermore, generations of scholars from many disciplines have puzzled over the origin and veracity of the ancient text. It is generally agreed that there was more than one version of the story in ancient Israel, and that the biblical account is a composite text extracted from those earlier, ancient versions. In addition, the Genesis account is only one of several flood narratives from the ancient Near East, and is likely to be dependent upon them.5

Various geological studies have looked into whether these common narratives might have arisen from a collective memory of one historic flood in the region, possibly due to rising sea levels following an ice age.6 Textual scholars, too, have not ruled out the idea that the biblical flood, while highly mythologised in the way it is told, may have its roots in a historical event. Moriz Winternitz, the Austrian scholar renowned for his work on flood myths at the turn of the twentieth century, seriously entertained the idea that local traditions might have been based on actual occurrences.7 In general, however, textual scholars take the view that the various elements of these legends were passed from one culture to another, adapted in each case to match their own cosmological and theological views – the Genesis account, for instance, has some features in common with the earlier Epic of Gilgamesh. Flood narratives are typically more concerned with teleology than with the modern-day approach to historical account – that is to say, they are less interested in giving a chronology of events or a scientific description than in exploring the nature of both God and humanity, and with offering, retrospectively, an account of human purpose.

‘Un-creation’

The account of the deluge begins in Genesis 6:1–7 with a dystopian vision of a world so corrupt, violent and depraved that there is no hope of restoring peace, goodness and justice. God is presented in somewhat anthropomorphic terms as being unable to bear the sight of this implosion of evil, and determined to bring it to an end – to ‘blot out from the face of the earth people together with animals and creeping things and birds of the air’.8

Rather than this being an unleashing of punishment or divine vengeance, however, the theological sense is of a reverse recapitulation of the earlier chapters of Genesis, making the flood narrative a kind of ‘un-creation’, or a reversal of the original creation story. Five chapters earlier, in the creation story, the earth was brought out of the midst of a chaotic swirl of water in the darkness. Having first introduced light, to make day and night, on the second ‘day’ God made the earth emerge from the watery chaos by suspending some of the water above the sky, and holding the rest below the earth (thus reflecting ancient Hebrew cosmology):

So God made the dome and separated the waters that were under the dome from the waters that were above the dome. And it was so. God called the dome Sky.9

Moving forward to Noah’s story, we learn that

In the six hundredth year of Noah’s life, in the second month, on the seventeenth day of the month, on that day all the fountains of the great deep burst forth, and the windows of the heavens were opened. The rain fell on the earth forty days and forty nights.10

By ceasing to suspend and suppress the upper and lower tranches of water, God allowed everything to return to its un-created state.11 But in the midst of ‘un-creation’, a second thread in the narrative emerges: God, we are told, stopped the progression of a total ‘un-creation’ and initiated a second creation by saving one prototype family with all the potential of the original, unspoiled creation. Thus Noah and his family, one pair of every kind of animal, and seven pairs of each kind of animal that were of sacramental significance in Hebrew thought became the subjects of a remaking of the creation account.12

The flood story as religious myth therefore stands less as an account of a capriciously judgemental God, and more as a story that encapsulates themes of creation, justice, salvation and future hope. This is particularly important for interpreting one of the central issues in the story – why a supposedly loving God would create the world and then initiate such a catastrophic disaster.

Cultural and theological shifts

By the early twentieth century, the idea of ‘un-creation’ was largely lost on the popular imagination; furthermore, the idea of creation itself had undergone a complete reinterpretation in mainstream Christian theology in response to the scientific and geological advances of the nineteenth century. Archaeological finds across the Near East were showing that these biblical texts were not the only ancient historical narrative, and that it was even possible that these texts may have borrowed from earlier ancient sources. Meanwhile geologists from Charles Lyell (1797–1875) to Charles Darwin (1809–1882) had not only challenged the notion of a young earth, but their work also implied the ancient creation narratives to be teleological rather than historical accounts. The nineteenth century, then, was much taken up with concerns over what it meant for the Bible to be an inspired or authoritative text in light of this new knowledge. Yet as the early decades of the twentieth century unfolded, bringing with them the previously unimagined suffering of the First World War, the more pressing questions addressed to theology asked where God was in such catastrophic suffering, and whether the Western world could ever think of God and faith in quite the same way again – something that Knights’s interpretation of the flood in The Deluge brings into focus.

In his book The Church of England and the First World War the scholar and Anglican priest Alan Wilkinson noted that there was little compunction in the opening years of the war about adopting biblical language of battle and sacrifice to call people to war, and to boost morale.13 Literary historian Lionel Adey also argued that religious imagery found in hymn collections sung in Edwardian schools was in part responsible for a tendency to conflate national identity with the Kingdom of God, thus making it possible to persuade a generation of young men to march to war believing that God was on their side.14 Yet as Wilkinson pointed out, this use of biblical language, and especially of apocalyptic imagery, ‘encouraged a view of the war as a straight conflict between good and evil, Christ and Anti-Christ, God and the powers of darkness’, and ‘offered an eschatological escape from wrestling with the moral ambiguities of contemporary human history’.15 As the war continued there was a growing distaste for this use of religious language to justify or prolong the conflict, and while artists and poets alike reflected on the morality of the war and the complex questions raised by unimaginable suffering and loss, at a popular level these concerns were framed in blunt and heartfelt terms – why does God let bad things happen to good people? One theological issue that came to the fore in Knights’s lifetime was theodicy – the defence of the goodness of God despite the existence of evil; another was the related but distinct matter of whether God could suffer.

Writing during the First World War, theologian Peter Taylor Forsyth undertook a lengthy exploration of theodicy in The Justification of God,16 in which he observed that the ‘doctrine of progress’ widely held throughout nineteenth-century Europe was completely exploded by the war and its ‘revelation of the awful and desperate nature of evil’.17 He alluded to the flood story, saying that there were some who, in the darkest days of the war, wondered whether the destruction of the world and ‘the salvation of a very few in some ark to re-stock the new aeon’ could possibly be squared with belief in a God who is loving and good.18 In exploring how God’s goodness can be justified in the face of such catastrophic disaster, he argued that God’s action for the world is its own justification; he is thus often seen as pre-empting the neo-orthodoxy that followed the war years. To a degree, Forsyth ends in arguing for faith despite complete answers. In this regard his argument is somewhat reminiscent of the book of Job, in which a sequence of questions is raised concerning why good people suffer. As the book eventually works its way towards a resolution and a reply from God, the answer begins with the suggestion that Job and the other characters in the book have been asking the wrong questions; their questions are framed as a demand for an explanation, but the answer is presented not as propositional explanations but as the revelation of God’s presence.

A different but related theological concern had already been gathering some traction before the war, and continued to figure large in theology throughout the twentieth century: questions surrounding God’s ability to suffer or feel emotional pain, and whether that suffering would affect God’s interaction with the created order, are addressed in the doctrine of the impassibility of God. This idea, adopted into early Christian thought from Greek philosophy, asserts that God does not undergo changes of emotional state and can thus only ever act towards the created order in pure goodness and wisdom. An impassible God is one of complete moral purity who is never capricious or prone to unpredictable changes of mood. The impassibility of God was more or less universally accepted in Christian theology from the early centuries of the Church until the nineteenth century. Yet as theologian Richard Bauckham has pointed out, while the stability of an impassible God was an attractive alternative to the capriciousness of the Greek deities, ‘to the modern mind it produces a notion of a God who is “static” – unmoved by the human predicament, and unwilling either to help or to sympathise’.19

By the closing decade of the nineteenth century, theologian Andrew M. Fairbairn had challenged the doctrine of impassibility, and other English-speaking theologians followed suit. In 1917 H.M. Relton said, ‘There are many indications that the doctrine of the suffering God is going to play a very prominent part in the theology of the age in which we live’,20 and his words proved accurate. As theology unfolded in the interwar years, the idea prevailed that God did experience emotional pain, and that this completely affected the relationship between God and creation.

The idea continued to develop, until nearly three decades later, during the Second World War, theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote, ‘God is weak and powerless in the world, and in precisely this way, and only so, is at our side and helps us’.21 Following the Second World War, the theology of the suffering God was further developed until it gradually became the majority view in protestant Christian theology of the twentieth century. Jürgen Moltmann, a leading proponent of the idea, wrote in 1972 that ‘When God becomes man in Jesus of Nazareth, he not only enters into the finitude of man, but in his death on the cross also enters into the situation of man’s godforsakenness’.22

There are multiple threads of Christian theology, as well as texts from the Hebrew and Christian scriptures, that make perfect sense when viewed through this lens. The passion and death of Christ, for instance, rather than being viewed as a transactional and correctional sacrifice while an impassible God looked on in moral perfection, becomes an act in which God suffers with, as much as for, humanity – the cry of dereliction coming not just from the dying Christ but from the heart of the suffering God. Returning to the flood narrative, this too takes on a different cast when read from the point of view that God suffers with humanity. Now, rather than God ‘blotting out’ humanity without so much as turning a hair, the story is as deep a trauma for God as it is for those facing the flood.

The idea of the suffering God is certainly not without its critics, and it is entirely possible to conceive of a dynamic God who simply acts, while remaining impassible. Nevertheless, the mood of the century created the context for this theological shift. Although theodicy and the (im)passibility of God are distinct ideas, both came to the fore as a response to the way the excessive trauma and suffering of the First World War caused people to question accepted ideas about God. Once a highly optimistic view of human progress came to a halt with the horrors of war, the pressing need was to find a way of articulating clearly whether God cared about the world and had the power or the will to change, help or sustain it.

Winifred Knights and The Deluge

There is no direct evidence that Knights, when painting The Deluge in 1920, set out to make any deliberate visual statements either about the war or about theological ideas being in flux. However, it seems unavoidable that the mood and thinking of the time, as well as her own experience of the war, affected her work. While studying at the Slade in London (1915–17 and 1918–20), Knights had been taught by Henry Tonks to draw on her ‘subconscious imagination’ to interpret subjects for painting, by which he meant ‘the power to make use at the present moment of something put away in the past’.23 There is, then, a high likelihood that painting a scene such as that of The Deluge would lead her to draw on personal experience, and the desperate plight of her figures does seem to reflect traumas that she had been through or heard about. The anxiety and panic on their faces – including her own self-portrait that appears twice in the group – might be drawn from Knights’s experience of a terrible industrial accident in London in 1917; her brutal, grey landscape seems suggestive of the sludge and ‘thick green light’ of Wilfred Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ (1920); and the colours of the bare earth may recall the deaths of so many her own age who, in the trenches of northern France, had quite literally drowned in mud.

Knights originally planned a picture that included the ark, with animals being loaded onto it; unlike Owens, it seems she did not deliberately set out to make a point about the apparent absence of God.24 Yet the ark sliding away almost unnoticeably in the background of her final composition for The Deluge emphasises the desolation of the figures in the foreground. In Knights’s painting, just as surely as in Owen’s poem, God seemingly disappears without comment.

By painting The Deluge using contemporary figures, architecture and landscape, Knights placed an ancient story in a modern context, and this, too, is profoundly theological, for theology is not merely the study of what people believed in the past, but how ancient myths and belief systems are reimagined and reinterpreted from one generation to the next. Had she placed the scene historically, a flat acceptance of God’s judgment as it was understood in ancient times might have been implied; instead this is replaced by a compassionate depiction of desperate and anxious people in the present tense. Yet Knights does more than make the story contemporary – she also makes it personal by using her self-portrait and those of her family and friends within the painting. Although this may have been motivated by practical concerns surrounding the availability of models, the result is a theological image that places the ‘narrator’ within the story. As with literary forms such as the memoir or epistle, by including herself within her own work an artist conveys a particular vulnerability and ownership of that work, one result of which is to invite the reader or viewer to encounter the work with a more interior perspective. ‘Maybe by telling you my story, you can better tell yours’,25 wrote American poet Mary Karr, or as novelist and memoirist Frederick Buechner put it, ‘My story is important not because it is mine, God knows, but because if I tell it anything like right, the chances are you will recognize that in many ways it is also yours’.26

Fig.2

John Martin

The Deluge 1834

Oil paint on canvas

1683 x 2584 mm

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

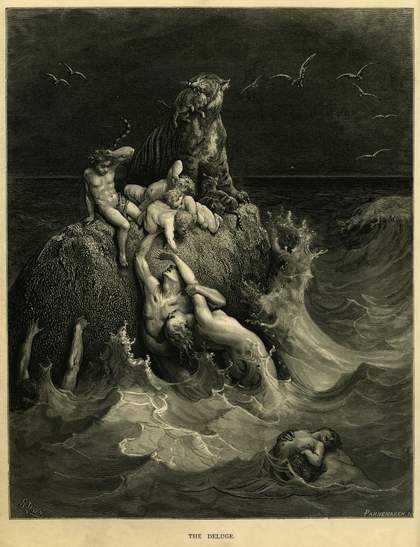

Fig.3

Gustave Doré

The Deluge 1866

Frontispiece to Doré’s illustrated edition of the Bible, La Grande Bible de Tours, Tours and London 1866

Knights’s painting might also be viewed as having a similar message to Owen’s ‘The Parable of the Old Man and the Young’. Just as Owen used a biblical narrative to accuse the masters of war of rejecting God’s preference for mercy, so Knights, in placing the ark beyond reach, could be asking questions of human authority just as much as of divine intent.

Knights’s theological distinctiveness is further highlighted by its contrast with the way other artists have depicted the same scenes. In Knights’s painting there is no dramatic indicator of God’s judgement, as there is in the rolling waves in John Martin’s epic painting The Deluge 1834 (fig.2). Furthermore, Knights’s figures are painted with a certain compassion for their plight; there is no suggestion that they deserve their fate, unlike the naked, slightly orgiastic figures in Gustav Doré’s earlier woodcuts The Deluge (fig.3) and The World is Destroyed by Water, from his 1866 illustrations for the English Bible.

There are multiple examples of artworks that depict the ark being loaded with animals, with little or no reference to the story’s darker aspects. In Edward Hicks’s 1846 painting Noah’s Ark (fig.4), for instance, the only reference to destruction and chaos is the brooding sky, while the undated lithograph Noah’s Ark (D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield) by Nathaniel Currier (1813–1888) is a scene of considerable calm and order. By contrast, Knights’s original sketches included the loading of the ark, but when pressure of time led her to simplify her composition, for her it was the ark that was most dispensable, and the plight of the frightened crowds that held her attention.

Fig.4

Edward Hicks

Noah’s Ark 1846

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

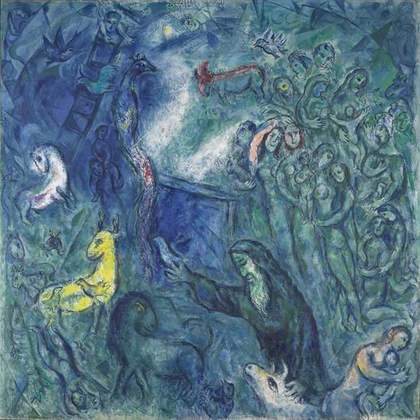

Fig.5

Marc Chagall

L’arche de Noé 1961–6

Musée National Marc Chagall, Nice

Marc Chagall, painting L’arche de Noé (Noah’s Ark) (fig.5) more than forty years after Knights created The Deluge, captured something of the God who suffers with humanity, who by then figured large in the theological imagination. Chagall painted the ark in his signature blue, a haven of serenity at the centre of the composition, while a chaotic swirl of figures cascade away into the watery green in the right of the painting. However, there among the drowning figures Chagall placed the figure of Christ. For Chagall, salvation is presented as a dual image: while there is tranquillity in the rescuing image of the ark, Christ’s bodily presence remains among those who are suffering. Knights seemingly operated at the hinge between these ideas, and her painting could reflect a pause at a moment of theological revision, on the one hand rejecting the idea that human catastrophe could be God’s judgement, while on the other hand not yet identifying the presence of God. Knights encapsulates a world standing in a moment of theological crisis, questioning whether God has the power to help, or is even present at all.

The biblical flood narrative, as we have seen, is open to multiple interpretations, and the depiction of its themes in any given era will never tell the story straight, but rather, as the nineteenth-century poet Emily Dickinson put it, will ‘tell all the truth, but tell it slant’27 – from calm or even festive depictions of Noah’s ark such as those by Hicks and Currier, to Martin’s apocalyptic judgement scene, to the suffering Christ depicted by Chagall. Working in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, Knights’s painting was particular to her time in the way that it highlighted certain emotional themes and theological ideas. She made central what had previously seemed the peripheral concerns of the flood narrative, highlighting the desperation and panic of those who are waiting for help that never comes. The way was opening up for a generation of artists, poets and theologians to reimagine a God beyond the trenches, who could not be unmoved by human devastation. For Knights, however, the suffering God had not yet materialised, and her painting thus subtly interrogates the biblical narrative, asking where God is found when there is real, pressing need.