In the four years after its completion The Doll’s House appeared in four major exhibitions: the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, the Glasgow International Exhibition in 1901, the Wolverhampton Art and Industrial Exhibition in 1902 and the spring exhibition of the New English Art Club in London in 1903.1 Purchased in late 1900 by the artist’s older brother Charles, the painting was subsequently donated to the Tate Gallery in 1917.

It was perhaps appropriate that the work should get its first public airing in Paris, the city with which Rothenstein had been closely associated since spending three and a half years there as a student. British painting was represented in two spaces at the Exposition Universelle: the British Pavilion in the Rue des Nations and the British section at the Grand Palais. The former space was dedicated largely to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century masters and the latter restricted to art made after May 1889, which allowed the inclusion of late works by several artists who had recently died, such as Edward Burne-Jones, John Everett Millais and Frederic Leighton. The British section was housed in four rooms and a corridor and featured 397 paintings (including watercolours) by 282 artists. As space was limited, the works were tightly packed.2

As might be expected from an exhibition of contemporary art arranged according to national affiliation, the British section was viewed with much anxiety. Since the first exhibition of the New English Art Club in 1886, there had been much debate over whether the Royal Academy could claim to represent the best in modern British art. From this point onwards there was growing pressure from critics such as D.S. MacColl to widen the scope when selecting exhibitions of British painting and to include the works of artists who, like Rothenstein, did not exhibit at the Academy.3 This, however, brought with it fresh concerns. With many of these young, non-Academy artists training in Paris, there was a perceived danger of British art becoming too French. What would be the implications if the British section in Paris looked simply like a pale imitation of the French school? The national restrictions also caused problems when it came to non-British artists living in Britain. James McNeill Whistler, John Singer Sargent and Edward Austin Abbey were among the most important artists working in Britain in the 1890s, but at the Exposition Universelle they were classed as Americans.

Fig.1

Laurence Alma-Tadema

Spring 1894

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Even despite these issues, summing up ten years of British painting in such a small place was never going to be an easy task. The 1890s was a difficult decade to digest, with no one style or group of artists dominating the art world. As such, the British section had to find a way of accommodating a wide range of pictures, from classical history painting to rural naturalism, second-wave Pre-Raphaelitism to impressionistic landscapes, formal portraiture to contemporary problem painting. Visitors to the British section would have encountered such varied works as Laurence Alma-Tadema’s Spring 1894 (fig.1), William Frederick Yeames’s Defendant and Counsel 1895 (Bristol Museums, Bristol) and John MacWhirter’s Morning: Isle of Arran 1898 (Aberdeen Art Gallery, Aberdeen). Royal Academicians, led by their President Edward Poynter, still made up the vast proportion of the exhibitors and received the highest plaudits (the two medals of honour were bestowed upon Alma-Tadema and William Quiller Orchardson), but there were signs of new blood also, most notably the work of Charles Shannon and William Rothenstein.

Reaction to the British section was mixed. Ernest G. Halton, who reviewed the exhibition at length for a special edition of the Art Journal, was begrudgingly positive, admitting that while the section was ‘scarcely one which can be considered representative of British art of the last decade’ it did at least ‘produce a restful and satisfying effect which is pleasing to the tired visitor’.4 As this comment suggests, he did not think The Doll’s House – hardly a restful painting – worthy of mention, preferring pictures with a rather more straightforward approach to storytelling, such as Arthur Hacker’s dramatic The Cloister or the World? 1896 (fig.2) or Seymour Lucas’s Phyllis is My Only Joy 1898.

Fig.2

Arthur Hacker

The Cloister or the World? 1896

Bradford Museums and Galleries, Bradford

Other critics were less forgiving. R.C., writing for the New York Tribune, considered the British section ‘one of the most depressing in all the Grand Palais’, laying the blame squarely at the feet of the Academy – Poynter in particular – whose pictures were typified by their ‘inert mediocrity’.5 Among those to escape his biting criticism were Albert and Henry Moore, George Frederick Watts and John Lavery. The real ‘salvation’ of the section, however, lay in three paintings: Charles Shannon’s self-portrait Man in a Black Shirt 1897 (fig.3), David Young Cameron’s The Avenue and Rothenstein’s The Doll’s House (fig.4).6 These were all appreciated for what we might call their Whisterlian or Rembrandtesque qualities: their use of strong uncluttered compositions and simple colour schemes, and their ‘vitality’ and unpretentiousness. The subject of the paintings was seen as largely irrelevant: The Doll’s House was praised for being ‘a study in light, tone and colour so new and so masterly that the human significance of the figures is ignored’.7 There is no doubt that Rothenstein’s work benefitted greatly from the hold that formal criticism would have on the future of British art – an ironic fate, perhaps, in light of its literary inspiration.

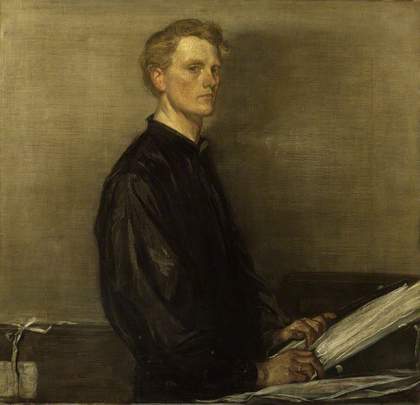

Fig.3

Charles Shannon

Man in a Black Shirt 1897

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig.4

William Rothenstein

The Doll's House 1899–1900

Tate

Official recognition for The Doll’s House came in the form of a silver medal, one of twenty-six awarded to the British section, following the two medals of honour given to Alma-Tadema and Orchardson and six gold medals awarded to George Clausen, Alexander Stanhope Forbes, Sir George Reid, John Macallan Swan, John Henry Lorimer and Edward John Gregory.8 Rothenstein’s appearance among the medals is notable for the fact that, unlike the vast majority of the listed names, no letters appear after it, highlighting his independence from major art institutions. He was also significantly younger than the majority of his fellow exhibitors.

By November of 1900 Rothenstein had already succeeded in selling The Doll’s House to the man who would become one of his most consistent patrons: his older brother Charles Lambert Rothenstein (later Rutherston). Charles was six years older than William and had shown artistic talent as a teenager before following his father into Bradford’s flourishing textile business.9 In the 1890s, encouraged by his younger brother, he started collecting art, frequenting exhibitions of the New English Art Club and mixing in many of the same circles as William and, later, their brother Albert. As Charles Rutherston later recalled:

I had now come to the conclusion that the cultivation of the modern school of English art was well worth-while and I decided that this must be my definite policy … later on I began to collect examples of ancient oriental pottery, bronzes and carvings which developed into an ever-increasing mania. I felt, however, that my duty was with the living as well as with the dead, and that my present-day artists, in many cases unrecognised, were morally entitled to support.10

Rutherston would go on to be a keen supporter of such artists as Gwen John, Wyndham Lewis, Eric Gill and Paul Nash, as well as a key figure in the Bradford Arts Club.11 At the heart of his collecting practice was the idea that art should be shared, on which basis he regularly loaned his artworks out to galleries or teaching establishments so that they could be seen by as large an audience as possible. When in 1926 he offered the bulk of his collection to Manchester Art Gallery it was on the basis that a proportion of them would be available to any local art schools that wished to exhibit them, a scheme which operated successfully for many years.12

Rutherston’s purchase of The Doll’s House was one of many that he made from William, without which Rothenstein would undoubtedly have struggled to make ends meet, as few other major collectors showed regular interest in his work. He recalls that he ‘gratefully accepted’ his brother’s offer for the painting, ‘as I had returned to town with empty pockets’.13 Disappointment followed, however, for shortly after Charles bought the painting word came around that a rather more high-profile patron was interested. ‘It may interest you to know,’ Augustus John wrote, ‘that [Henry] Tonks and [John Singer] Sargent independently arrived at the same conclusion, viz. that your Doll’s House was the best painting in the Exposition’.14 Sargent duly made a bid – which proved too late. As Rothenstein admitted to his father on 26 November 1900: ‘From a business point of view it is a pity Charles bought my picture, as [John Singer] Sargent is very keen to get it – of course this would have led to other pictures being sold – you know the snobbishness of human kind’.15 Sargent buying The Doll’s House would certainly have been a coup for Rothenstein and might have attracted other collectors to his work. The timing, however, was not to the artist’s advantage and it seems as though his brother was reluctant let such an important work leave his hands at this stage.

If he wasn’t happy to let Sargent have the painting – let alone the collector James Staats Forbes, who was said to have offered one thousand pounds for it – Charles Rutherston was at least happy to let it travel to exhibitions.16 In 1901 it enjoyed its second major public airing at the Glasgow International Exhibition and in the following year it was one of a significant group of contemporary pictures exhibited at the Wolverhampton Art and Industrial Exhibition. Responding to recent exhibitions of British art such as the British section at the Paris Exposition Universelle, the organisers of the Wolverhampton show, led by the brewer and collector Laurence Hodson, were keen to put together a collection that highlighted the achievements of the New English Art Club over those of the Royal Academy. It signalled, in a sense, a changing of the guard, establishing the right of the New English artists (described by the catalogue as ‘the younger and intenser artists of the present day’) to be seen as the most significant artists working in Britain during that period.17 ‘It was at Wolverhampton,’ wrote the leading critic Frank Rutter in 1933, ‘[that] I was first roused to consciousness that here and now, all around me, was growing up a really great school of British painters … For the first time in the provinces the “New English” were in, and popular Academicians were conspicuous only by their absence.’18 D.S. MacColl was similarly gratified: ‘At Wolverhampton,’ he wrote in July 1902, ‘a definite taste has prevailed; the committee has had the courage of its advisor’s convictions; popular names have been of no account, youth and outsidership have been no hindrance to presence and good places; and the result is a limited, well arranged, and deeply interesting collection’.19

The significance of the Wolverhampton exhibition was not lost on artists at the time. ‘The show at Wolverhampton seems to be an important one,’ remarked Albert Rutherston in a letter to William, adding: ‘you will be well represented’.20 Rothenstein showed five paintings – Vezelay Cathedral c.1896 (private collection), The Browning Readers 1900 (Bradford Museums and Art Galleries, Bradford), An Interior (c.1900), Portrait of a Young Man: Augustus John (1899, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) and The Doll’s House – along with two portrait medals, six drawings and six prints. His brother Charles loaned several items beyond The Doll’s House, including works by Augustus John and Auguste Rodin and prints by Francisco Goya. The gallery Carfax and Co also lent work by Charles Conder. Also well represented were Charles Shannon, Charles Ricketts, William Nicholson and William Strang, the latter of whom had enjoyed significant patronage from Laurence Hodson, whose collection drove the show. Strang’s The Temptation 1899 (Tate T07518; fig.5), one of a series of paintings commissioned for Hodson’s library and described by Walter Sickert as work ‘of the greatest importance’, was one of the highlights.21

Fig.5

William Strang

The Temptation 1899

Tate

Photography © Tate

Wolverhampton sent out a message that was picked up by subsequent exhibitions, most notably the survey of British art held at Bradford’s Cartwright Hall in 1904 and the exhibition of Independent Art of Today held at Thomas Agnew’s gallery in London in 1906, which confirmed that Rothenstein and his New English contemporaries were now being taken seriously by collectors and critics alike.

By the time Rothenstein exhibited The Doll’s House, by popular demand, at the New English Art Club in spring 1903, it was already a familiar and well-regarded work, which may explain why the committee chose to hang it – as Rothenstein wrote to his father – ‘in the centre of the wall’.22 This was the painting’s first outing in London and its last major exhibition for some time. This exhibition was dominated by representations of domestic interiors, to which The Doll’s House was seen to have a close relationship. Viewers, nevertheless, could not help but notice the difference between The Doll’s House and the artist’s more recent work, such as The Browning Readers, with its rather less disquieting atmosphere.

Between 1903 and 1917, The Doll’s House seems to have been publicly exhibited just once, in a 1910 exhibition of Rothenstein’s work held at Bradford’s Cartwright Hall. It was, however, visible at Charles Rutherston’s Bradford house, and it was here that the artist Paul Nash saw it during a visit to the city in 1914. He left at least two records of this encounter. In a letter to Michael Sadler (now in the Tate Archive) Nash described the ‘joys’ of Rutherston’s collection, from the pots and bronzes to the paintings by Augustus John and Charles Conder, noting that ‘“The Doll’s House” is really a “stunner”.’23 In a letter to the poet Gordon Bottomley, meanwhile, he wrote of ‘dear Charles Rothenstein at whose house we stayed that night & half the next day. He was delightful & entertained us splendidly … Stunning early Johns, all sorts of Conders and the picture The Doll’s House, which did quite floor me’.24

The enthusiasm of young artists such as Nash may have convinced Charles Rutherston that The Doll’s House belonged in a national collection. The Tate Gallery owned one painting by Rothenstein, his 1906 Jews Mourning in a Synagogue (Tate N02116), which was presented to the gallery by Jacob Moser on behalf of the Anglo-Jewish community in 1907. In 1917 Rutherston offered Tate The Doll’s House, along with Ambrose McEvoy’s The Ear-Ring (Tate N03176; fig.6), which he purchased at the New English Art Club in 1911 upon the occasion of its first exhibition. In doing so, he seemingly sealed the reputation of the painting as Rothenstein’s finest and most widely exhibited work.

Fig.6

Ambrose McEvoy

The Ear-Ring exhibited 1911

Tate

Photography © Tate

In 1924 Charles Aitken, then director of Tate, claimed that The Doll’s House seemed to ‘sum up and conclude the 1890–1900 period – the Yellow Book aesthetic period with faint Rossetti reminiscences’.25 Certainly the painting has tended to fall more regularly into displays of Victorian or 1890s art than in twentieth-century exhibits, despite the fact that the impact of the painting was felt most clearly in the 1900s. Within the context of Rothenstein’s career – and Tate’s collection as a whole – it is clearly a difficult painting to manage, as it does not necessarily share the mood of his other paintings, especially those representing domestic contentment, such as Mother and Child 1903 (Tate T05075) or The Princess Badroulbadour 1908 (Tate N03953). It is hard to imagine the word ‘haunting’, which Frank Rutter used to describe The Doll’s House, being applied with confidence to many of Rothenstein’s paintings, with the obvious exception of its Vattetot companions, Le Grand-I-Vert 1899 (Manchester City Art Galleries, Manchester) and The Butcher’s Shop under the Trees 1899 (Tate N05946).26

Having been categorised as both romantic and realistic, literary and ‘purely pictorial’, The Doll’s House can be hard to place. It has nonetheless been a constant feature of permanent exhibitions across the years, gaining a reputation as Rothenstein’s most familiar and critically acclaimed work. In 1933 Rutter wrote: ‘It may be that Sir William Rothenstein has painted pictures more accomplished in technique, even more poignant in conception … Yet I am inclined to doubt whether any other painting by him has ever excited an admiration so widespread and intense’.27 Robert Speaight, the artist’s biographer, was of a similar opinion, declaring in 1962: ‘There are few visitors to the Tate Gallery whom it has repelled; for many of them it will always stand upon the summit of William’s art’.28 Reviewing his friend’s career in the introduction to the 1950 Rothenstein memorial exhibition held at the Tate Gallery, it was The Doll’s House that drew the majority of Augustus John’s attention – and not just, one suspects, on account of his appearing in it.29

More recently, the painting has appeared in important touring exhibitions, most notably the 2000 exhibition 1900: Art at the Crossroads, which celebrated the centenary of the 1900 Exposition Universelle and sought to embrace the catholicity of international art during this period. Here The Doll’s House appeared, rather anomalously, in a section on ‘The City’, which also contained work by Pablo Picasso, Edgar Degas and the American painter John Sloan.30

The exhibition of The Doll’s House as part of Tate’s ‘BP Walk through British Art’ launched in June 2015 deserves some attention. Here it was hung in the ‘1900’ room, to the left of Gwen John’s portrait of Dorelia in a Black Dress 1903–4 (Tate N05910; fig.7). This juxtaposition has neat aesthetic resonances – both paintings share a predominantly brown palette – and personal connections, Dorelia being the mistress of Augustus John. Dorelia’s pose clearly echoes that of Augustus in Rothenstein’s canvas: her arms folded across her chest and her gaze extended back towards the viewer. The room in which she stands (most likely a rented room in the French countryside, like that of The Doll’s House) is distinctly bare, with the merest hint of a fireplace in the background.

Fig.7

Gwen John

Dorelia in a Black Dress 1903–4

Tate

Photography © Tate

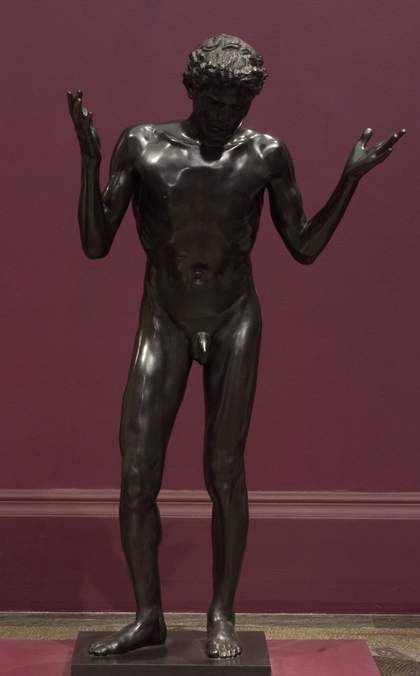

Placed a few feet in front of these two paintings was Lycidas c.1905 (Tate N02763; fig.8), a bronze sculpture by James Havard Thomas. Like The Doll’s House, Thomas’s work appears to takes its cues from a literary text – usually thought to be John Milton’s 1637 poem of the same name – although the reference is, once again, a complicated one. As David Getsy has noted, ‘Thomas preferred a name that would invoke the question of the statue’s meaning without attempting to provide any convincing entry into interpretation’, a tactic rather reminiscent of Rothenstein’s approach in The Doll’s House.31 Although the older Havard Thomas had exhibited with the Royal Academy since 1872, the year of Rothenstein’s birth, the controversial rejection of Lycidas in 1905 drew him into more openly progressive circles. His first solo show was held at the Carfax and Co gallery (co-founded by Rothenstein) in 1909 and he would go on to exhibit with Rothenstein at exhibitions of the Society of Twelve (founded in 1904). Despite the figure’s nakedness and lively – albeit ambiguous – gesture, the black bronze establishes a clear connection between this young man and the shadowy figure of Augustus John in The Doll’s House.

Fig.8

James Havard Thomas

Lycidas 1902–8

Tate

Photography © Tate

Fig.9

Herbert Draper

The Lament for Icarus 1898

Tate

Photography © Tate

The connections between The Doll’s House and the painting hung to its left are less clear. Despite its similarly golden-brown hues, Herbert Draper’s dramatic The Lament for Icarus 1898 (Tate N01679; fig.9) is exactly the kind of painting from which Rothenstein and his New English Art Club companions were seeking to escape. The classical theme, gratuitous use of male and female nudity, melodramatic poses and overall busyness of the canvas would certainly not have been to Rothenstein’s tastes. Although Draper, who shared Rothenstein’s Académie Julian training, was not an official member of the Royal Academy, he exhibited there regularly and gained popular acclaim for his mythological scenes. Draper’s popularity would come to haunt Rothenstein: in 1904, following their successful inaugural exhibition, in which the locally-born Rothenstein had exhibited several works along with those of many New English Art Club members, Bradford’s Cartwright Hall Gallery used their profits to purchase Herbert Draper’s The Golden Fleece 1904 (Bradford Museums and Galleries, Bradford).32 Bringing Draper and Rothenstein together, however, serves as an important reminder of the eclecticism of turn-of-the-century culture: this is just the kind of juxtaposition, after all, that visitors may have encountered during the very first outing of The Doll’s House at the Paris Exposition (where Draper exhibited Calypso’s Isle 1897, Manchester City Galleries, Manchester). It is difficult for a modern viewer to understand the impact of The Doll’s House without some sense of what the artist was fighting against, and Draper’s The Lament for Icarus serves very well in this regard.