In 1909 the art critic T. Martin Wood published an essay in the Studio on ‘The Problem of Modern Interior Painting’, in which he considered the tendency of contemporary artists to represent domestic interiors and the issues they faced in doing so. While noting the influence of seventeenth-century Dutch painting, ‘the present return to all this interior incident,’ he argues at one point, ‘began in Mr. William Rothenstein’s The Doll’s House’.1

The phrase ‘all this interior incident’ refers to an obsession with what Kenneth McConkey has described as ‘small, Spartan, perfectly painted interiors’ that were shown at the biannual exhibitions of the New English Art Club during the period 1900 to 1903.2 Perhaps because of the association between the New English Art Club and impressionist landscapes, this phenomenon was much remarked upon by critics of the time, marking as it did a distinct shift in the predilections and direction of the influential exhibiting society. Fourteen years after the club’s foundation, the mood was clearly changing: a new generation, headed by figures such as William Rothenstein, were beginning to assume a leading role. The ‘interior’ was the subject with which they sought to establish themselves.

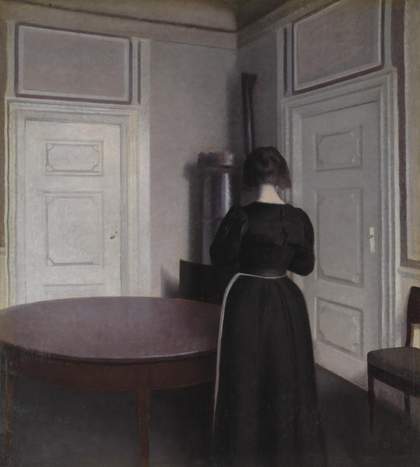

Fig.1

Vilhelm Hammershoi

Interior 1899

Tate

Photography © Tate 2016

They were not alone in choosing to focus on the interior at this historical moment. Not only were there significant, recent precedents – including Whistler, whose Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1 1871 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) continued to loom large over the period, and Degas, whose 1868 Interior was similarly influential – but artists across the world were turning their hands to the subject.3 Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, who shared Rothenstein’s Académie Julian education, were among the key practitioners in France and remain perhaps the best-known artists to work in this genre. The paintings of the so-called Boston School in America (including Edward Tarbell, yet another Académie Julian graduate) and the work of Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershoi, who spent time in London at the turn of the century, are also interesting in this context, sharing as they do distinct qualities with canvases by Rothenstein (see Hammershoi’s Interior 1899, Tate N04106; fig.1).4 Although the interior dominated the New English Art Club for a short while only, it continued to adopt a central role in Edwardian painting as a whole, becoming a key feature for Camden Town Group artists such as Harold Gilman (see Edwardian Interior c.1906, Tate T00096; fig.2) and other painters associated with the Slade School of Art and the New English Art Club, including Gwen John who would go on to make the sparsely decorated interior central to her practice (see A Lady Reading 1909–11, Tate N03174; fig.3).

Fig.2

Harold Gilman

Edwardian Interior c.1906

Tate

Photography © Tate 2016

Fig.3

Gwen John

A Lady Reading 1909–11

Tate

Photography © Tate 2016

A contemporary critic expressed the English situation well in a review of the winter exhibition of 1902:

For the past few years the New English Art Club has been dominated by the personalities of a few members who have made the domestic picture the dominant note of the club’s exhibitions. I do not mean the millinery-baby domestic picture of the Royal Academy, rather the home picture of the Dutch School. The explanation is simple enough. Mr. Orpen, Mr. Rothenstein, Mr. Russell, Mr. Muirhead have chosen to paint the rooms in which they live, and the choice and simple possessions that an artist gathers about him. This example of dogged hard work has been infectious.5

The use of the word ‘infectious’ is instructive; indeed, many critics found themselves rather disturbed by the number of interiors that appeared in the club’s biannual exhibitions. F.J.M, writing in the Speaker after visiting the spring exhibition of 1902, went as far as to describe the tendency as a ‘cult’ that ran the risk of being ‘staled by infinite repetition’.6 He pondered whether the similarity of many of the paintings suggested ‘the presence somewhere of a property room which sundry enthusiastic and maybe promising art-students take their turns at painting’, concluding that they were, in general, ‘rather the language of art than art itself’. The critic D.S. MacColl – a good friend of many of the artists involved – had made a similar point a few months before, claiming that ‘the critic of some future time’ might struggle to tell the interiors of William Orpen and Rothenstein apart, noting that their respective works, A Window 1901 (private collection) and Interior 1901 (private collection) were ‘singularly alike in subject and conception’.7

Fig.4

William Orpen

The Mirror 1900

Tate

Photography © Tate

By 1903, even Rothenstein himself seemed frustrated, complaining to his father that ‘I am, I confess, a little bored to find half the New English filled with imperfectly understood & executed examples of my own style’.8 Part of the issue here was that he and Orpen often painted their wives who, being sisters, looked very similar. They appeared to share a taste for furnishings, as suggested by the repetition of the green-shaded lamp in A Window and Interior, and for particular poses.9 They also enjoyed trading in artistic allusions, such as the wink to Van Eyck in Orpen’s The Mirror 1900 (Tate N02940; fig.4), or the hat-tips to Whistler and Puvis de Chavannes in Rothenstein’s The Browning Readers 1900 (fig.5), the latter of which depicts both Alice, seated, and her younger sister Grace, the future Mrs Orpen, standing by the bookshelf.10 It is clear, nevertheless, that Rothenstein felt that Orpen was being needlessly imitative. As he later recalled, ‘for a time, Orpen’s pictures were confused with mine; indeed I think Orpen would have agreed that at this period he was somewhat influenced by my interiors’.11

Fig.5

William Rothenstein

The Browning Readers 1900

Bradford Museums and Galleries, Bradford

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein

With retrospect, however, it would be unfair to describe all the New English Art Club interiors as confirming to a rigid type. In fact, between the various practitioners of the genre – which also included Albert Rutherston, Walter Russell, David Muirhead, Mary and Ambrose McEvoy, Henry Tonks and Francis Dodd – there was a wide range of responses to the genre. The core features are gloomy rooms, occupied by smartly dressed women engaging in private activities: reading, looking at art, or staring out of the window (in the true Dutch style). Some of the women seem dissatisfied, as if questioning their relationship to the domestic sphere, while others seem perfectly comfortable in their surroundings. The rooms are usually sparsely decorated, in such a way as to lend significance to what objects are there, objects which, as Kenneth McConkey has suggested, seem to ‘function by association’.12 Although the painting style is largely crisp and precise, an element of mystery is almost always present: the prints and paintings on the walls of these interiors, for instance, are very rarely identifiable. Areas of shadow, or the awkward juxtaposition of figure and furniture, meanwhile, suggest the externalisation of fraught psychological states.13

Beyond these features, however, various licenses were taken. Some of the paintings were given literary titles, or titles suggesting a narrative, while others were known, simply, as Interior. Some introduced a male presence into the canvas – Orpen’s The Chess Players 1902 (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) is a good example – while others played off the contrast between differently aged models, as seen in Francis Dodd’s Afternoon in the Parlour 1902 (Glasgow Museums, Glasgow). In Albert Rutherston’s work, meanwhile, there was a distinct effort to get beyond the middle-class mood of his contemporaries: Song of the Shirt 1902 (Bradford Museums and Galleries, Bradford) and The Confessions of Claude 1901 (UCL Art Museum, London) are situated in a very similar environment to that of Alice and Grace in Rothenstein’s The Browning Readers, hinting at the direction Rutherston would later explore in his great 1906 painting Laundry Girls 1906 (Tate N04996).

Within Rothenstein’s own oeuvre there is also a distinct range. Figures – usually women – posed in domestic interiors are a feature of his work from the very beginning of his career, as images from his Paris sketchbook (1889–93) show.14 In the mid-1890s he consistently returned to this theme, producing several paintings showing a well-dressed young woman standing or sitting in an interior that is largely bare, excepting a few select images on the wall and one or two stray items or pieces of furniture. In one case – the early Interior: Lady with a Hat 1891 (fig.6) and Seated Woman in Interior c.1891 (private collection) – the same model is shown from two different sides, her face partly covered by a hat. On the wall behind her are pictures by other artists; in the case of Seated Woman in Interior the picture appears to be Edgar Degas’s painting of Carlo Pellegrini (then owned by Louis Fagan, who worked for the British Museum).15 The same trend is evident in two works owned by Tate: Woman Standing in a Doorway c.1894 (Tate N04595; fig.7) and Miss Edith Lockyer Williams 1893 (Tate N05407; fig.8). The paintings on the wall may be obscured, but nevertheless form a major feature of the composition.

Fig.6

William Rothenstein

Interior: Lady with a Hat 1891

Museums Sheffield, Sheffield

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein

Fig.7

William Rothenstein

Woman Standing in a Doorway c.1894

Tate

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.8

William Rothenstein

Miss Edith Lockyer Williams 1893

Tate

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

It has been suggested that Woman Standing in a Doorway relates to the 1894 painting Porphyria (also known as Porphyria’s Lover; private collection).16 Here Rothenstein places his model on a striped sofa, in a grand and revealing dress. On the wall behind her is a large mirror, in which we see the head of a male figure, turning away from the viewer. This man was modelled by Rothenstein’s friend, the artist Charles Conder, who was pictured alone in several other paintings of the period – which, again, juxtapose the figure with a bare interior containing framed works of art.17 Porphyria can be read as a rather gaudy dress rehearsal for The Doll’s House, in its representation of a troubled male and female relationship unravelling in a gloomy interior setting.18

Beyond 1900 Rothenstein was disinclined to infuse his interiors with such an ominous spirit – the possible exception being his curious double portrait Eric Gill and Alice Rothenstein c.1913 (fig.9) – which appears to look back directly to The Doll’s House.19 In this painting Gill takes the role of Alice, seated with his head in his hands, while Alice, dressed in black and white, stands beside him. Rothenstein himself is represented by one of his paintings – the 1904 landscape The Deserted Quarry (Bradford Museums and Art Galleries, Bradford) that hangs above the mantelpiece. As with The Doll’s House, the two figures appear to be caught up in some sort of emotional impasse. A similar air of tension can be found in some of Rothenstein’s interiors of the 1900s, especially those in which Alice looks out of the window, or poses on the bright green sofa with her head in her hands.20 However, there are also many images of domestic serenity, most particularly The Browning Readers and the many paintings featuring Alice and William’s children, such Mother and Child 1903 (Tate T05075). One could even go so far as to describe some of these later interiors as bordering on the mawkish, if not showing increasing interest in a room’s display of material goods as opposed to the emotions of its inhabitants. A good example of this would be the 1905 painting In the Morning Room (fig.10), created only six years after The Doll’s House, but seemingly belonging to another world entirely. The empty room of The Doll’s House and the bare dress of its inhabitants have been replaced by a light-filled middle-class interior, with colourful curtains and flowers on the mantelpiece. Any tension between the figures is relieved by their physical intimacy, with Alice’s hands holding her two children close.

Fig.9

William Rothenstein

Eric Gill and Alice Rothenstein c.1913

National Portrait Gallery, London

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein

Fig.10

William Rothenstein

In the Morning Room c.1905

Manchester City Galleries, Manchester

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein

Comparisons such as these suggest that it may have been misleading of Martin Wood to put forward The Doll’s House as the originator of the ‘interior’ phenomenon. Of the two paintings, In the Morning Room probably shares more similarities with other interiors painted by New English Art Club members during this period. Indeed, if we were to put Rothenstein at the centre of this so-called cult – as he deserves to be – it makes more sense to describe The Browning Readers, painted after The Doll’s House but exhibited at the club three years before, as the painting that kick-started ‘all this interior incident’. In fact, if we follow an argument made by Max Beerbohm in his 1903 review of the New English Art Club, The Doll’s House is not the rule, but the exception.21 It stands apart from other interiors of this period.

The central contention of Beerbohm’s review is that the conditions of modern life at the turn of the century had changed the way in which people relate to the domestic interior and that ‘the modern mode of life is incompatible with culture of the domestic sentiments’.22 Beerbohm describes contemporary society as an ‘age on edge’ and discusses how representations of interiors either reflect or deny the reality of living in a world of ‘whirling overwork and overplay’.23 Although the charge is a serious one, it is expressed with Beerbohm’s characteristic humour, encouraging readers to imagine works of art that successfully portray ‘ladies and gentlemen whose bodies are still vibrating from the motion of motor-cars’ (as opposed to the ‘galaxy of solid gentlemen and gracious ladies’ of yore).24 Beerbohm’s praise of John Singer Sargent as an artist perfectly suited to this new world (dis)order also has an element of tongue-in-cheek about it, revolving as does around the idea that the brilliance of Sargent’s paintings lies in their superficiality – a statement that may not have been intended as a straightforward compliment.25

Sargent is treated with far more respect, however, than most of the artists in the exhibition, many of whom receive stinging criticism for their failure to grasp what Beerbohm sees as the central ‘problem’ of the modern interior: its impersonality. He writes:

If you enter a typical modern house, you are aware, through some subtle message borne in on you by its atmosphere, that it is not lived in – merely slept in, gone in and out of, by the lessees of it. Nor do you feel that it has any characteristic of its own. It might belong to anybody – to everybody. It is as impersonal as the open air. It is not ‘an interior’. That is a thing to be found only if you go to call on people who are living years behind the time. It results from a quiet life lived consistently by persons deeply interested in one another. It results, in fact, from culture of the domestic sentiments. And here comes in an awful stoke of irony, which is felt by any visitor to the New English Art Club. ‘Interiors’ are the very things which all the younger men are industriously striving to paint.26

In an age in which interiors have ceased to exist in their familiar form, notes Beerbohm, they have suddenly become strangely popular. However, rather than address the shifting mood of the domestic, artists of the New English Art Club appeared to be blithely unaware of it. They were – if you choose to believe Beerbohm’s argument – chasing a mood that no longer existed.

Fig.11

Henry Tonks

The China Cabinet c.1902

Birmingham Museums Trust, Birmingham

Although the main offenders are not named, perhaps to temper Beerbohm’s criticism, reference to original catalogues allows us to track down the works in question. One of them is Henry Tonks’s The China Cabinet c.1902 (fig.11) which shows a young woman in a pale blue dress, bathed in sunlight, inspecting a piece of china in one hand, while the other rests on the door of a cabinet. The interest in china ornaments is, as we have already seen, typical of New English Art Club interiors, reminding us of Rothenstein’s The Browning Readers or Francis Dodd’s Afternoon in the Parlour. Taking it as a given that Tonks’s intention was to represent a ‘lived-in’ interior, Beerbohm claims that the resulting representation falls short of the artist’s expectations. The scene, he feels, aims at cosiness, but finds artificiality: ‘The lady handles the piece of china tenderly enough; but there is no pride of possession; she is wondering what it will fetch’.27

Beerbohm identifies the same problem in works by Mary McEvoy (An Old Letter 1902), Ambrose McEvoy (Convalescence 1902) and William Orpen (The Sleeping Baby 1902). Mary McEvoy’s effort at sentiment is deemed a ‘dead failure’, while McEvoy’s model is described as ‘a high-school girl who, having broken down through over-work, has been ordered to take the rest cure, and is outwitting the authorities by reading on the sly’.28

The New English artists are shown, again and again, to be pursuing domestic subjects – such as motherhood – only to discover the

‘inhuman jumpiness which modern life has forced on humanity’.29

Had these paintings set out to explore this theme from the offset then they might have attracted the critic’s praise. Beerbohm believed, however, that only one artist deliberately addressed the conditions of modernity, capturing as he did the true spirit of the ‘age on edge’:

One of them, in one of his pictures, has frankly chosen a theme from which all domestic sentiment is excluded; and his is the one quite satisfactory achievement. He calls it ‘The Doll’s House’ … Here, we feel, is no home. That is what the painter meant us to feel.30

The phrase ‘one of them’ is disingenuous: the artist in question, after all, was Beerbohm’s close friend.31 The criticism, nevertheless, is interesting, recognising as it does the strange relationship The Doll’s House had with other interiors exhibited at the New English during this period – let alone other interiors in Rothenstein’s oeuvre. We may not agree with Beerbohm’s conclusions about modern life (many of which are exaggerated, one senses, for comic effect), but there is no doubt that his comments can help us understand the very particular qualities of The Doll’s House.

Beerbohm’s review reminds us of the most obvious difference between The Doll’s House and the majority of the New English interiors: the absolute plainness of the room it represents. Sparseness may have been an attribute of the New English interior, but the starkness of The Doll’s House is almost unrivalled (with the possible exception of Rutherston’s Song of the Shirt). The traditional painting or print on the wall that is a feature of almost all of Rothenstein’s other interiors is noticeably absent. There are no ornaments here, no furniture, no fabulous frocks to catch the eye. The interior is not an appealing one and was never going to attract the attention of amateur interior decorators – as was the case with Rothenstein’s The Browning Readers.32 The room does not pretend to be homely in any shape or form, or to represent (as The Browning Readers does) the artist’s pride in his own domestic surroundings: it depicts instead a dark corner of a room that is being occupied on a temporary basis. The idea that anyone would want to stay in this space for any significant amount of time is refuted by the man’s dress. He is prepared to leave the room as soon as he can.

New English interiors were, largely speaking, phenomena rooted in urban experience. Although the city is only occasionally visible through the windows, most of the paintings represent London interiors. Here, again, The Doll’s House is an exception. Painted in rural France, in cheap lodgings, the work has much more in common with the interiors Walter Sickert painted in Venice in 1903–4 than with its New English Art Club companions. The delight Rothenstein appears to have taken in the dinginess of the Vattetot interior reminds us of a comment he made about Sickert in his memoirs: ‘I had known many poor studios in Paris, but Walter Sickert’s genius for discovering the dreariest house and most forbidding rooms in which to work was a source of wonder and amusement to me’.33 Although Sickert’s best-known interiors were painted after The Doll’s House, the painting nevertheless feels as though Rothenstein was deliberately channelling the spirit of his friend, with whom he had spent time earlier that summer.34 The vague tension and theatrical atmosphere is certainly reminiscent of earlier work by Sickert, such as The Rehearsal: The End of the Act 1885 (private collection); it also anticipates (or inspired) later paintings, most obviously Sickert’s Ennui c.1914 (Tate N03846; fig.12), which transposes the action of The Doll’s House into a London interior, populated by a couple whose dissatisfaction with their lot rivals that of Rothenstein’s painting.

Fig.12

Walter Sickert

Ennui c.1914

Tate

Photography © Tate

Another, perhaps unexpected influence behind The Doll’s House is the artist whom Beerbohm discussed at the beginning of his 1903 review: John Singer Sargent. Sargent was open in his admiration for the painting and even asked to buy it.35 For those familiar with Sargent’s flamboyant turn-of-the-century portraits, this may seem surprising. However, in the early 1880s Sargent had produced a series of paintings representing everyday life in Venice that offer an intriguing comparison with The Doll’s House. Many of these feature a small group of figures, dressed in dark clothes, posed in gloomy interiors or side streets. The same mixture of controlled tension and barely-contained boredom that is central to The Doll’s House is very much present in these works. This is most obvious in Sargent’s A Street in Venice 1880–2 (fig.13), a study of two figures – a man and a woman – playing out an uncertain drama on the threshold of a shadowy interior.36

Fig.13

John Singer Sargent

A Street in Venice 1880–2

Clark Institute, Williamstown

Fig.14

James Pryde

The Doctor exhibited 1909

Tate

Photography © Tate 2016

As this comparison suggests, despite Rothenstein’s centrality to the proliferation of interiors at the New English Art Club, The Doll’s House makes little sense in this context alone. In fact, it belongs more to the artist’s 1890s interiors, such as Porphyria, than it does to those of the 1900s, such as The Browning Readers. Looking back to works by Degas, Whistler, Sargent and Sickert, it also points forward to work by members of the Camden Town Group and to paintings by artists such as James Pryde, whose 1909 canvas The Doctor exhibited 1909 (Tate N05172; fig.14), picks up where Rothenstein left off – and, as it happened, rarely returned.