Despite their coarse and fragmentary appearance, Roszak’s post-war sculptures were meticulously designed before their fabrication. As curator Paul Cummings has explained, Roszak was ‘a compulsive draftsman who produced hundreds of small sketches that often led to larger drawings, which were themselves frequently transformed into sculptures’.1 In 2015 Tate acquired a cache of drawings that relate to The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) and provide new insights into the genesis of the work. While the majority of these drawings date from 1951–2, coinciding with Roszak’s entry to the international competition, four are dated between 1959 and 1968, suggesting that Roszak remained preoccupied by the sculpture and the possibility of its full-scale realisation long after the competition. This short essay will examine Roszak’s group of drawings for the sculpture and consider how they shed new light on the development of the work.

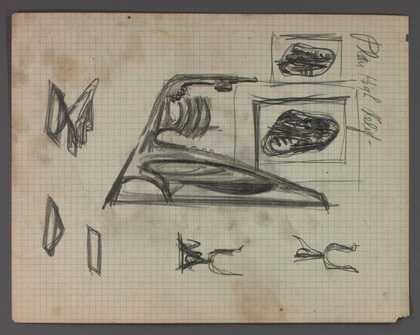

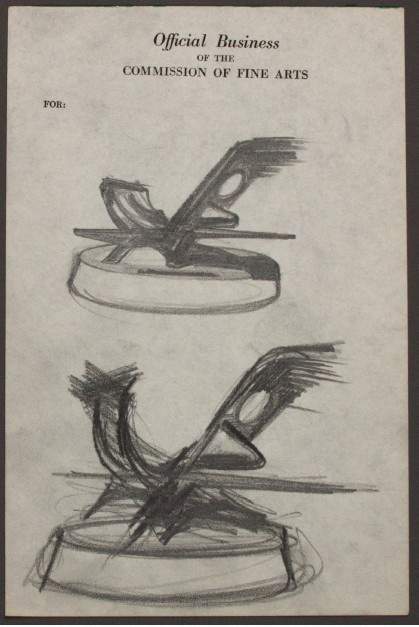

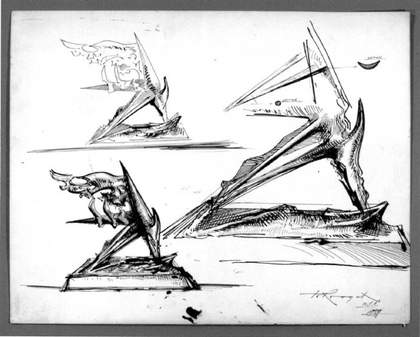

Fig.1

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Graphite on paper

Support: 215 x 277 mm

Tate L03770

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

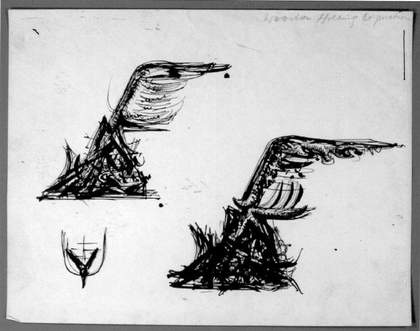

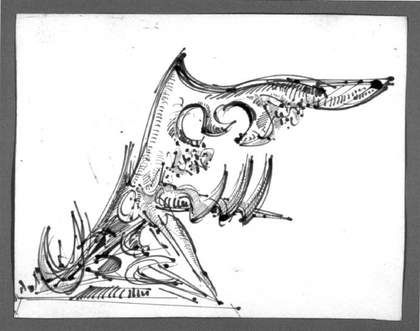

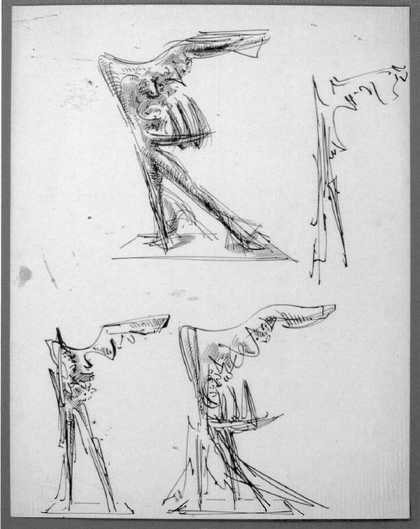

Fig.2

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Ink on paper

Support: 217 x 278 mm

Tate L03776

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Several sketches among the drawings are particularly noteworthy for the way in which they vary from the final sculptural form. For example, an early rendering of the side view of the work shows Roszak to have considered a slicker, more streamlined design. Returning to Roszak’s earlier constructivist style, this drawing shows the forward surge of the sculpture to have originated from a distinctly futuristic jet-like form (fig.1). These drawings also suggest that Roszak was considering a forked design for the work when viewed from above – an idea retained, to some extent, in the more symmetrical profile as seen from the sculpture’s shortest side. In several drawings Roszak’s sketched out what this U-shaped profile would look like (see, for instance, the lower-left corner of fig.2).

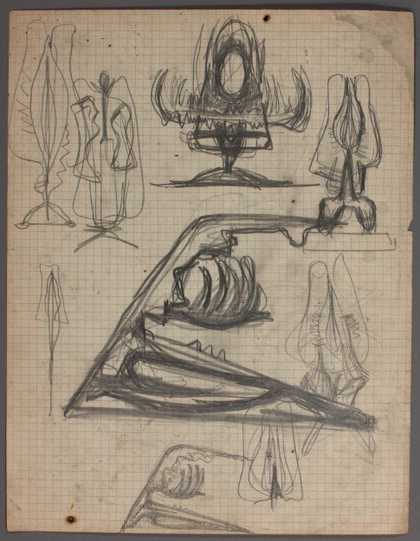

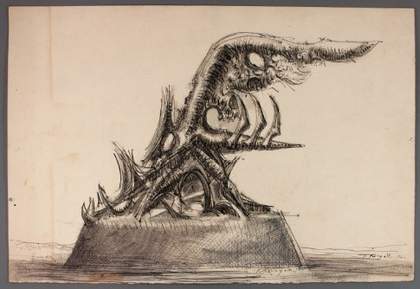

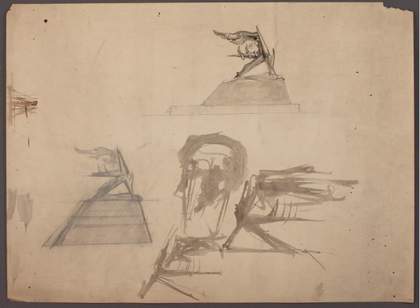

Fig.3

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Graphite on paper

Support: 215 x 277 mm

Tate L03783

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

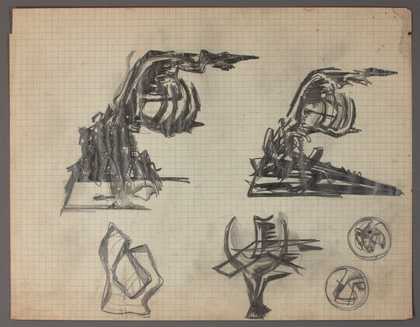

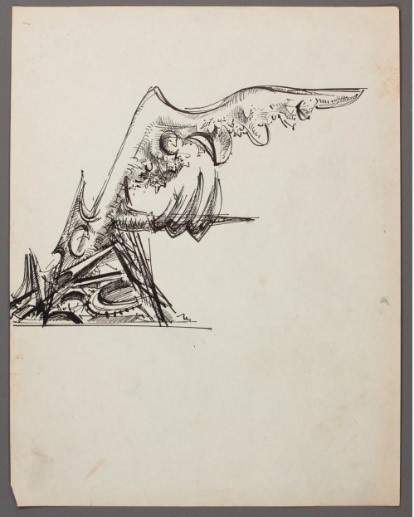

Fig.4

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1952

Graphite on paper

Support: 730 x 1075 mm

Tate L03790

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Fig.5

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1952

Ink on paper

Support: 675 x 1073 mm

Tate L03789

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Even the drawings that show Roszak developing the menacing claw formation so characteristic of the sculpture’s profile (such as fig.3) reveal that the top of the upper winged form was originally rendered as a smooth, streamlined appendage in contrast to the more turbulent fluttering element of the final work. The decision to abandon this earlier, sleeker profile appears to have been a key one; a pair of otherwise similar drawings reveal the differing effects produced when the upper-most corner of the wing is peaked in a sharp point (fig.4), as it does in the final maquette, as opposed to adopting a more gentle, streamlined curve (fig.5).

Fig.6

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Graphite on paper

Support: 215 x 277 mm

Tate L03775

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Fig.7

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1968

Graphite on paper

Support: 202 x 134 mm

Tate L03788

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Another aborted idea revealed by these drawings concerns the base for the work, which was imagined to be circular (figs.6 and 7). The latter of these – drawn on the letterhead of Washington, D.C.’s Commission of Fine Arts, on which the artist served from 1963 until 1969 – is the latest sketch in this group and suggests that Roszak may indeed have returned to the design in the context of a government project. Although it might well be regarded as a different work to that held by Tate – especially given its date – its form bears considerable similarity to the design Roszak had developed some fifteen years earlier.

Fig.8

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Ink on paper

Support: 225 x 283 mm

Tate L03773

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Fig.9

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Louis XIV of France 1665

Marble

Height: 800 mm

Palace of Versailles, Versailles

The size and prominence of the distinctively baroque ‘French curve’ shape, which in the final sculpture appears towards the top of the flame-like form, changes across many of the drawings, and in some instances is moved to the underside of this wing (fig.8). Roszak once named Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s 1665 portrait of King Louis XIV (fig.9) as his favourite sculpture, which invites comparison between Roszak’s florid forms and the exuberant curves and curls he so admired in the famous Baroque bust.2

Fig.10

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1960

Ink on paper

Support: 378 x 560 mm

Tate L03768

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Fig.11

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Ink and charcoal on paper

Support: 560 x 380 mm

Tate L03769

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Fig.12

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1959

Ink on paper

Support: 278 x 217 mm

Tate L03780

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

In several drawings the lower portion of the sculpture is characterised by a dense vegetal undercroft (figs.10 and 11) instead of the more open struts that give the final design the appearance of a creature on legs. As Paul Cummings has observed, Roszak’s ‘sculptural process of welding and brazing also informed the textures of the drawings’.3 In some of the designs that evidence this same attention to the final surface texture of the sculpture, this briar of thorny roots appears to include something like a barbed tail (fig.12) – an idea that was ultimately realised in a more subtle whiplash line that snakes down what reads as the rear of the creature, curling around the side of the textured ground of the sculpture (fig.13).

Fig.13

Theodore Roszak

The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952, detail

Tate N06163

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Fig.14

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1959

Ink on paper

Support: 277 x 353 mm

Tate L03774

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Varying across the drawings, the central thorn shapes in the sculpture sometimes appear enclosing, like the bars of a cage, and thus allude more explicitly to imprisonment in line with the subject of the competition. However, in keeping with Roszak’s desire for a more optimistic monument, a later drawing appears to consider removing these elements altogether, providing the design with an even more angular, forward thrusting profile (fig.14). Roszak may have used a ruler to execute this drawing. As Cummings has observed, Roszak ‘manipulated shapes throughout sheets and sketches’ combining ‘freehand and ruled lines ... to arrive at a desired configuration’.4

Fig.15

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Ink on paper

Support: 280 x 209 mm

Tate L03778

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

The sense of motion at the core of Roszak’s design is conveyed perhaps most powerfully by some of the artist’s looser ink drawings, which sacrifice detail in favour of brisk calligraphic gestures (fig.15). Here, the sweeps of ink relate to how the artist sought to conceive the work: ‘The first thing I tried to do was to create a series of lines that would give me a sense of monumentality’, he told interviewer James Elliott in 1956. ‘I thought that the monumental aspect of a project of this kind would have to be affirmative. I couldn’t believe that a man imprisoned and held prisoner, hostage, against his own desires, could give rise to the same kind of objective monumentality as a man who would be perfectly willing to sacrifice himself for his political belief.’5

Fig.16

Winged Victory of Samothrace 220–185 BC

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Fig.17

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Ink on paper

Support: 278 x 217 mm

Tate L03777

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

The heroic implications of this idea were ones that Roszak understood. ‘I know that men have certain strong beliefs about their political positions and they are perfectly willing to consciously accept the consequences of their beliefs’, he told Elliott. ‘To me, this is a kind of hero’s deed, and therefore I wanted that to become a heroic thing ... To me it is necessary to give it this thrust of defiance, and then the wings and flourish of triumph.’6 Roszak appears to have turned to the famous ancient Greek sculpture known as the Winged Victory of Samothrace (fig.16), whose form is closely echoed on one sheet containing four designs (fig.17). Another drawing features wispy horizontal marks under the arc of the wing, which further evoke feathers (see fig.2). The reference to the ancient sculpture is less manifest in the completed maquette, but as Cummings has observed, often ‘small fragments of a larger image would suggest a new form of motif, and the initial image would be dropped forever’.7

Fig.18

François Rude

La Marseillaise (The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792) 1833–6

Arc de Triomphe, Paris

Fig.19

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Sherman Monument 1902

Grand Army Plaza, New York

Art historian Joan Seeman has linked The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) to François Rude’s monumental sculpture La Marseillaise 1833–6, which adorns the Arc de Triomphe in Paris (fig.18), but her suggestion might equally extend to a broader range of triumphant sculptures featuring a forward thrusting winged figure. In New York, the figure of Victory in Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Sherman Monument 1902 (fig.19) located on the south-east corner of Central Park comes to mind. Roszak’s absorption of the formal characteristics of triumphant sculpture is as evident in the final maquette as it is in the drawings, which feature a thrusting windswept form underpinned by strong, taut legs.

Fig.20

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1952

Graphite and ink on paper

Support: 560 x 760 mm

Tate L03787

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Fig.21

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Ink on paper

Support: 207 x 257 mm

Tate L03771

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Fig.22

Theodore Roszak

Study for Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Ink on paper

Support: 466 x 589 mm

Tate L03772

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

One critical aspect of the work that further supports its triumphant form is only revealed in the drawings. Roszak’s design for a tall, wedge-shaped base for the work is articulated across several sketches, confirming its importance to the artist. This bulky block often features an elongated angle at the rear of the sculpture, corresponding with the directional thrust of the wing, and establishes this base as an integral element of the design, rather than simply being a neutral plinth (see figs.20 and 21). In the most richly pictorial rendering of the sculpture, this plinth is shown in a turbulent landscape (fig.22). As art historian Joan Marter has pointed out, Roszak used this drawing to depict multiple views of the work within a single scene.8

Fig.23

Theodore Roszak

Monument to Unknown Political Prisoner 1951–2

Graphite on paper

Support: 214 x 277 mm

Tate L03785

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Tate

Fig.24

Theodore Roszak

Mandrake 1951

Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

Several sheets in the group show Roszak’s design for The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) alongside sketches for other sculptures. For example, in the lower half of one page there are images of a more elongated, horizontally orientated sculpture that has an insect-like appearance (fig.23). These drawings appear to relate to Roszak’s Mandrake 1951 (fig.24), a work roughly contemporary with Tate’s maquette. In another page catalogued as Mixed Sculpture Sheet 1951–2 (Tate L03786), Tate’s work appears surrounded by designs for other sculptures, including several related to Invocation II 1950–1 (fig.25) and Invocation III 1957–8 (fig.26).

Fig.25

Theodore Roszak

Invocation II 1950–1

Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Michigan State University, East Lansing

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

Fig.26

Theodore Roszak

Invocation III 1957–8

David Owsley Museum of Art, Ball State University, Munci

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

Fig.27

Installation view of Roszak’s 1956 touring retrospective, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, showing (left to right): Study for ‘Spectre of Kitty Hawk’ 1946 (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.), Spectre of Kitty Hawk 1946–7 (Museum of Modern Art, New York) and In Pursuit of an Image 1955 (location unknown)

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

The importance of Roszak’s preparatory drawings for understanding his sculpture should not be underestimated. Central to his artistic practice, Roszak’s drawings were sometimes prominently displayed alongside his finished sculptures, as was the case in his 1956–7 touring retrospective (fig.27).9 As the artist himself explained, drawing served ‘as a means for releasing any number of ideas that could not so readily be recorded in any other media’. It also acted, he explained, as an ‘agent’ by which he could ‘distill’ and ‘clarify’ his ideas.10 In this sense, the variations and revisions revealed by this group of drawings point to the key features of Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) as determined by the artist himself.