Fig.1

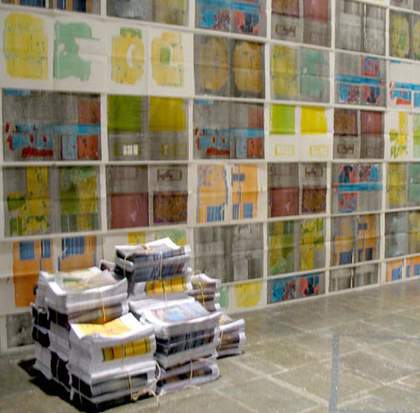

Gordon Matta-Clark

Walls Paper 1972

72 offset lithographs on newsprint paper

Overall display dimensions variable, each: 860 x 576 mm

Tate T14658

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

From 21 October until 10 November 1972, Walls Paper (Tate T14658; fig.1) was featured in a solo show of Gordon Matta-Clark’s latest work at the artist-run space 112 Greene Street in New York. The artist was twenty-nine years old at the time and had obtained an undergraduate degree in architecture four years earlier. But like his father, the Chilean surrealist painter Roberto Matta, his training in architecture would not manifest itself as a career in the profession. Instead, his artistic practice in New York, while deeply engaged with the architectural framework of the city, played with urban infrastructure in more unconventional ways. Matta-Clark treated the built environment as raw material for his practice, examining the ways in which buildings lived in a city – as part of a shifting, flawed system that represented multiple interests, functions and dysfunctions.

Fig.2

Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone

Gordon Matta-Clark installing Walls Paper at 112 Greene Street in 1972

Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone papers, circa 1860–2011, bulk 1940–2011, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

The show at Greene Street was the only time Walls Paper was exhibited during Matta-Clark’s lifetime. The work is derived from photographs of decaying buildings that Matta-Clark had taken on surveying trips in New York in the Bronx and, closer to home, on the Lower East Side.1 These source photographs, called Walls 1972 (see, for instance, Tate P14439–P14440), show buildings with their façades removed, so that the details of their interiors are exposed. Matta-Clark had the photographs printed in colour onto newspaper where they appear as murky rectangles, then covered a gallery wall floor-to-ceiling with the printed imagery (fig.2). Walls Paper also included bundles of newspapers printed with the wall images, which visitors were able to take away with them, and the following year Matta-Clark made a 144-page photobook from the work entitled Wallspaper 1973 (Tate T14659).

Perhaps first and foremost Walls Paper is a play on the idea of making a wall out of paper, and then papering a wall with images of other walls – the very kinds of walls that wallpaper is generally intended to cover over. The work therefore acts as a physical manifestation of Matta-Clark’s love of puns and wordplay. While technically Walls Paper functions not unlike wallpaper, the work forms a paper thin veil that exposes the thing that it hides, and as such palpably demonstrates the frailty of this effort by depicting the fragility of the walls themselves. Moreover, the delicacy of the newsprint means that the piece is in danger of decaying itself, much like the walls it abstractly depicts.

The starting point of Walls Paper is the imagery of failing walls, but the end result is that of phantom rectangles arranged linearly, some interfacing with each other, some reduced to line, some acting as foreground and some as background. It is a splotchy abstraction that offers up the shadowy remains of an architectural structure in flux and becomes an eerie palimpsest of buildings that exist, or existed, elsewhere. By taking photographs of walls that occupy the interstitial space between construction and destruction, Matta-Clark uses photography’s inherent uncanniness to layer different socio-economic systems – physical and psychological – upon each other.

As well as Walls Paper, the 1972 show at 112 Greene Street consisted of Matta-Clark’s very first ‘building cuts’: sections of flooring resting on the ground with photographs behind them showing their absences from the site from which they were taken, and a wall and door fragment placed on a table top, with Walls Paper as a backdrop. With images of walls on the walls and fragments of floors on the floor, the works acted out their own displacement, uniting site specificity and terrain vague.

Fig.3

Gordon Matta-Clark

Splitting 1974

Colour photograph

680 x 990 mm

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

The early ‘cuts’ that Matta-Clark displayed alongside Walls Paper were fragments extracted from buildings, but his work would later come to revolve around the absence of these fragments in the buildings themselves. In 1974 he cut a New Jersey row house in half, tilting the foundation to allow a persistent beam of light to penetrate the interior (fig.3). Matta-Clark also cut out the four corners of the house’s rooftop. Splitting, as the work was called, was bulldozed soon after Matta-Clark’s incision. From Splitting onwards the cut buildings became Matta-Clark’s primary work, a practice that was necessarily experiential and not object-based in that most of the buildings were only usable as sites and available because of their imminent destruction. In 1972, however, Matta-Clark was still exploring his various interests and ways of opening up the architectural environment with works such as Walls Paper.

Unlike the literalness of the building fragments, Walls Paper announces its artfulness through its unusual colour. Artist and dancer Carol Goodden recalled in 1985 that Matta-Clark ‘worked very hard with Joan Simon learning how to print in color on newsprint. He chose odd acid greens and yellows, and papered the walls of 112, making the inside of 112 look like a regular street scene.’2 Even as Goodden acknowledges the oddness of Matta-Clark’s colour combinations – blue/red, green/yellow and some dusky monochromes – she also allows that printed newspaper was very much a part of city life – as both reading material and, once read, casual debris. Matta-Clark highlighted this by also including the bundles of newspapers which visitors could take. As such, while Walls Paper might stick out aesthetically in a traditional museum context, in the un-refurbished space of 112 Greene Street it looked like a part of everyday life. In that sense, the dream space evoked by the colour of Walls Paper, as described by art historian Thomas Crow, could easily be a surreal one – the extraordinary emerging from the detritus of the everyday.3

Walls Paper as modernist critique

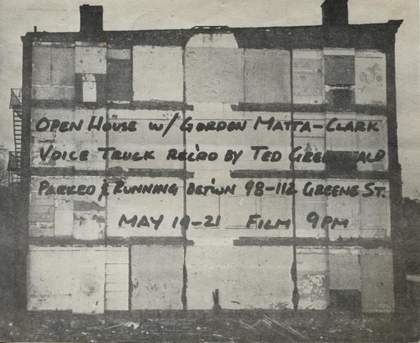

Fig.4

Gordon Matta-Clark

Invitation to a screening of Matta-Clark’s Open House 1972 featuring a source photograph for Walls Paper 1972

White Columns Archive, New York

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

At the same time, it is worth considering that Matta-Clark’s use of colour could function as an anti-art gesture. The source photographs for Walls Paper are black and white, easily legible and taxonomic (see, for example, the source photograph in fig.4, here used by Matta-Clark for a 1972 invitation). They play well within the context of high modernism – the characteristic flatness, geometry, formal clarity and abstraction that continued to dominate contemporary art criticism, in part through the persistent influence of the formalist critic Clement Greenberg. Yet the addition of colour in the final form of Walls Paper represents a deliberate departure from the deadpan aesthetic of contemporary photographic practices of the 1970s, including street photography and the black and white documentary style employed by conceptual and land artists. For photographers including Robert Smithson, Ed Ruscha, Diane Arbus and Gary Winogrand, the dominant position was one of impartiality, depicting the world from the point of view of a wry but ultimately detached observer. In 1973, the year after he made Walls Paper, Matta-Clark hand-coloured black and white photographs of graffiti for his Graffiti Photoglyphs – another example of the way in which he bucked contemporary art trends. Matta-Clark’s use of colour in Walls Paper was unconventional not only in the combinations he chose, but in the subjective associations colour invited, such that it constituted an overtly anti-systematic gesture. When in 1976 the Museum of Modern Art in New York finally presented a solo show by a photographer working exclusively in colour – William Eggleston – the press release acknowledged this bias against colour: ‘unlike most of their predecessors, whose color work has been either formless or too pretty, a new generation of young photographers has begun to use color in a confident spirit of freedom and naturalness’.4 Colour had also been seen as a hallmark of commercial photography. It defied the clarity of the grid aesthetic that Rosalind Krauss would later theorise as a spatio-temporal declaration of modernity.5

While the finished version of Walls Paper eschewed modernist aesthetics, the source photographs for the piece formally embraced them. One of the most legible photographs that Matta-Clark took for the Walls Paper project shows the interior of the shell of a four-storey apartment building. There are few signs of domesticity, save for three fireplaces lined with brick and some moulded rectangular elements in what might once have been a living or dining room. The photograph reveals the modularity of modern living and also the flimsiness of these enclosures. The interior walls that formerly defined the rooms in the space have all been removed, and only interruptions in the plaster (revealing the brick edifice) demonstrate the traces of where walls once stood. The building is doubly flattened to two dimensions – both by the act of being transformed into a photograph, and because it is no longer building, but wall – and thus becomes geometry.

Matta-Clark might have enjoyed flirting with high modernist aesthetics while positioning his work firmly in the here and now of New York’s crumbling domestic infrastructure. For wallpaper at its heart is a decorative device for domestic interiors, a vaguely feminine and distinctly bourgeois fashion statement that was itself subject to stylistic trends. That Walls Paper encapsulates those hopes while showing their futility is an effective act of camouflage. A contemporaneous review acknowledged the simulacrum of decoration that the work offered: ‘Matta’s material was anything that comes from a wrecked building either directly, like a piece of it, or indirectly, like a silkscreen from a photo or a photo. One wall in the gallery was covered with sheets of paper on which repeated images from a photo of wrecked walls had been silk screened. The sheets of paper were put on the wall the way wallpaper is put up. What Matta did was to put walls on the wall.’6 Matta-Clark effectively reduced the materiality of the wall to an image of itself, abstracting it and exploiting its flatness both in the represented image and its display.

Fig.5

Gordon Matta-Clark

Walls Paper 1972 (detail)

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

Photo © David Zwirner Gallery

There is another way in which Walls Paper toys with high modernist aesthetics. Matta-Clark turns critic Harold Rosenberg’s famous warning against the slippages between Jackson Pollock’s action painting and ‘apocalyptic wallpaper’ into something literal.7 With its motley colours occupying the entirety of the wall, Walls Paper superficially appropriates the all-over effect prized in abstract expressionist painting (fig.5);8 but instead of emulating the insularity of abstract expressionist aesthetics, Walls Paper insists on its social engagement.9 In this way Matta-Clark further expands Rosenberg’s idea of the canvas as ‘arena in which to act’, shifting it from studio to metropolis. That New York City was on the brink of bankruptcy in the mid-1970s meant that Matta-Clark’s project was undeniably informed by his surroundings. His apocalyptic wallpaper does not explode or beautify, but quietly pictures a capitalist economy in disgrace.

Contemporaneous critics did not always find the right terms to describe Matta-Clark’s project. Writing in Art News, critic Rosemary Mayer saw in Matta-Clark’s use of photography a ‘contemporary and literal sensibility’ married to an implicit romance for the ruin, with which Matta-Clark’s work inevitably engaged. As she put it:

Demolished buildings are flamboyant and romantic stuff. Matta’s involvement in presentation is justified since he had to find a way to deal with his chosen material that would allow the artist an area to operate in would not be overwhelmed [sic] and go unnoticed because of the overpowering materials. The wall papering worked in that it was a subdued, ordered and even witty way of presenting his material. But it was very reminiscent of Warhol despite the change in subject … That Matta’s is a contemporary and literal sensibility is evident in that he did not choose to paint or draw his materials but photographed it, or got the thing into the gallery. However Matta must also be considered happily romantic and expressive in his choice of materials.10

There is a contradiction here between Mayer’s description of Matta-Clark as a romantic and her insistence on the literalness of his project. By uniting these poles, Mayer finds the content of Matta-Clark’s work sincere in its emotional weight, while admiring its mechanical presentation. Yet Matta-Clark likely would have bristled at the label ‘romantic’. Far from fetishising urban ruins (or mourning their loss), Matta-Clark was a proponent of reconceiving these spaces, opening them up for new uses. While it is tempting to read an oblique reference to the gendered associations of wallpaper here too, by and large critics left such interpretations alone. Furthermore, when seen in proximity to the brute physicality of the building fragments, the subtlety of Walls Paper’s decorativeness may have been overwhelmed, especially in the barely converted industrial space of Greene Street, where wallpaper’s aspirational masquerade of an interior was so obviously rendered futile.

Challenges to abstraction, homages to pop

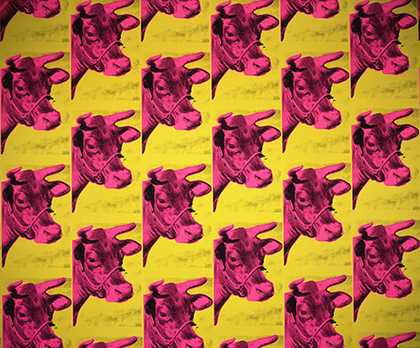

Fig.6

Andy Warhol

Cow Wallpaper (Pink on Yellow) 1966, reprinted 1994

Screenprint on wallpaper

Roll: 4572 x 711 mm, each: 1168 x 711 mm

Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

© 2017 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, NY

Through its contradictory engagements with high modernist aesthetics, Walls Paper was effective as a deliberate affront to abstract expressionism. For many critics, Matta-Clark’s use of screenprinting in Walls Paper recalled Andy Warhol’s painting practice, and even Warhol’s own foray into wallpaper. As critic John Perreault described Walls Paper in the Village Voice: ‘One huge wall is covered with strips of what he [Matta-Clark] calls “walls paper”, repeated photo images of those exposed walls I like so much myself. It is depressing, however, that one immediately thinks of Warhol’s cow wallpaper’ (see Andy Warhol, Cow Wallpaper (Pink on Yellow) 1966, reprinted 1994; fig.6).11 Perhaps what was disappointing to Perrault about the comparison was that it was so superficial – Matta-Clark’s wallpaper was all urban grit, with ruined walls repositioned to question the gap between debris and decoration, while Warhol’s cow wallpaper was overtly and playfully pastoral and patently commercial in its allusions. While thematically they could not have been more different, Matta-Clark’s use of the screenprinting technique and the reference to the decorative could not help but reference the aesthetics of pop art. Art historian Benjamin Buchloh has asserted how Warhol’s exhibition of cow wallpaper at Leo Castelli’s gallery in 1966 took on:

All the elements of modernism’s most radical and utopian promises – to evolve from the picture plane through sculptural object to architectural space; to educate the viewer from an attachment to iconic representation to a liberatory mode of the self-reflexive, the indexical sign, and the tactile mode of participation; and to abandon the confines of the private viewing mode of the easel painting in favour of the space of simultaneous collective perception – all those utopian promises are annihilated in this installation.12

But Matta-Clark’s rendition is not purposefully bland, not dispassionately ironic, and ultimately does not function as a rebuke of avant-garde sensibility. Instead, he offers another way of thinking through the possibilities of art in the social sphere, marshalling the collapse between newspaper and wallpaper as a connective tissue with communicative value.

Still, what role does screenprinting play in Walls Paper, aside from its commercial function as a means of producing wallpaper – the very product cited by Matta-Clark in the installation? It remains an open question whether Matta-Clark deliberately set out to engage with pop art through his use of the screenprinting technique; at the very least, he may have anticipated some comparison with Warhol. For Warhol, screenprinting offered a way to make paintings mechanically, a method through which he could further destabilise the heroic modernist role of the painter and the value of the individual painterly touch. Screenprinting’s ties to commercial graphic production appealed to Warhol but it remains unclear whether it carried the same associations for Matta-Clark. He may have found a useful guide in Warhol’s depiction of an endless cycle of production and consumption. Perhaps screenprinting offered a fittingly streamlined way for Matta-Clark to describe an analogous system in the architectural domain – walls once integral to urban development were now relegated to the fringes (if not geographically, at least in the cultural psyche) in an environment that necessitated new walls, new buildings. While both Warhol and Matta-Clark began these projects with photographs, Warhol appropriated his images from popular culture while Matta-Clark’s were the result of a certain kind of fieldwork. But despite vast differences in their source images, Matta-Clark may have been intrigued to see how Warhol’s early uses of screenprinting showed the format to be conducive to repetition, a build-up of graphic design to the point, sometimes most effectively, of illegibility.

Another reviewer recognised that Matta-Clark’s work departed from previous aesthetic trends. Preferring the building cuts displayed in front of Walls Paper to the installation itself, Art News critic Al Brunelle wrote of the show:

Inside, a photo of the last remaining wall of a demolished building, subjected to color permutations and printed by offset in continuous rolls, hung in long streamers on one wall of the gallery. Most engaging were actual extracted segments of old buildings. Displayed in close proximity were photos depicting the removal of these chunks, and the subsequent holes. By cheerfully ignoring the esthetic speculations raised by documentation, one is able to examine the segments simply as sculptural objects, in which case they are enticingly wistful and lovely. A weird and pragmatic individualism is at work here. Matta-Clark is lurching against the door-jambs of several reasonably chic current concerns, instead of bobbing and weaving through slickly and smoothly, like a real hitter. Probably sometimes he doesn’t pay attention to all the rules, and wanders off looking at the news with his own glasses.13

In Brunelle’s analysis, Matta-Clark thwarts documentation with both the chunks of floor themselves and the way he chose to represent the decaying walls of Walls Paper by screenprinting images on newspaper. The reference to the news is also compelling: Walls Paper is printed on newspaper, and while the piece operates as wallpaper, it can also act as a kind of blurry, disfigured version of the news. In this way Matta-Clark’s Walls Paper tells a vivid story of New York’s dire socio-economic condition.

While most reviewers of the 1972 exhibition seem to have found it compelling, like Brunelle many seemed more taken with the actual pieces of gutted buildings than the display of the representations of those gutted buildings. Walls Paper is nonetheless a key early work in Matta-Clark’s oeuvre in the way that it uses the wall as its raw material, responding to the conditions of its environment and dancing provocatively around the questions of aesthetic manipulation.

Photography’s ‘violable’ walls

Walls Paper is important in its embodiment of the major issues in Matta-Clark’s oeuvre, playing with themes of enclosure, ephemerality and decay while seemingly eschewing the photograph’s function as historical record. As we have seen, Walls Paper was a purposeful departure from the more deadpan style of photography practiced by many artists in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Through its jarring but faded colour combinations (which today enhance the periodisation of the piece), Matta-Clark announces that Walls Paper is not a document, eschewing the historical gravitas and objective presentation that black and white imagery might offer.

Difficult to position, Matta-Clark’s works on paper are still not fully incorporated into our understanding of his oeuvre. This is perhaps because the building cuts are so much more dramatic and, in their absence, foster a deeper sense of longing along with the promise of discursive recovery: the absent building cuts can be reanimated through our conversations around them, while the works on paper operate in more traditional ways. In the first monograph on the artist, published in 2001, art historian Pamela M. Lee wondered, ‘how, then, are we to contend with the status of Matta-Clark’s photographs?’.14 Artist Joseph Kosuth described how ‘[Matta-Clark] used a camera like he used a buzz saw. It was another tool for the physical conversation that went on.’15 Yet despite the importance of photography to his practice, Lee refuses to analyse, let alone illustrate, Matta-Clark’s numerous photomontages, which she dismisses out of hand, claiming they were ‘criticized by even his strongest supporters’.16 The overt manipulation of photography that Matta-Clark engaged in with Walls Paper is subject to the same dismissal, and is still something of a lacuna in our understanding of Matta-Clark’s oeuvre. Scholars have preferred to focus on Matta-Clark’s photographs and films as documents – they are often treated as records of the building cuts that help in situating his interventions in the metropolitan landscape. But he never abandoned photographic practice and his photo-collages of building cuts, with their off-kilter arrangements and uses of white space and strips of colour, very clearly announce that they are artistic statements in their own right.

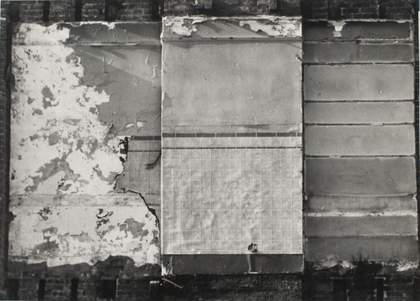

Fig.7

Gordon Matta-Clark

Walls 1972

Gelatin silver print on paper

381 x 527 mm

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

Like his photomontages, Walls Paper, rather than capturing an original experience, involves the viewer in new relations to objects and environments. In reproduction, the refusal of Walls Paper to conform to contemporaneous standards of photography is easy to overlook. This lack of conformity is not evident, for instance, in the black and white installation shots of 112 Greene Street from 1972, nor in the source photographs Walls, which display straightforward documentary-style elevations (see fig.7). But even in his photography, Matta-Clark had always envisioned his stance as disruptive and embodied – his position was defiantly non-neutral as a witness to the decay of New York City. As Matta-Clark declared, ‘I like the idea that the sacred photo framing process is equally “violable”. And I think that’s partly a carry over from the way I deal with structures to the way I deal with photography.’17 It is clear that Matta-Clark thought of his photographic works in dialogue with his building cuts, wielding both mediums to underscore our perception of space as fragmented, at once a presence and an absence. Yet while we can consider Walls Paper in conjunction with the building cuts with which it was displayed, it is also possible to see Walls Paper as the beginning of Matta-Clark’s cutting and conjoining of architectural photography that would eventually culminate in his photomontages. Walls Paper is neither documentary photograph nor collage, but on the precipice between.

In a 1977 interview Matta-Clark would later admit to his ‘abhorrence of flat art’ (perhaps a reference to Greenbergian formalism) and ask, ‘Why hang things on a wall when the wall itself is so much more challenging a medium?’.18 Walls Paper has it both ways: it engages walls, but it is very much about ‘flat art’ – flat photographs, and flattened buildings too. Ultimately, it was the permeability of the wall that Matta-Clark became engrossed with – and this could be exposed through the physicality of cutting or the reconfiguration of space through dislocated representations of it. According to Matta-Clark:

by undoing a building, there are many aspects of the social conditions against which I am gesturing: first, to open a state of enclosure which had been preconditioned not only by physical necessity but by the industry that profligates suburban and urban boxes as a context for insuring a passive, isolated consumer – a virtually captive audience.19

Both through his photography and the physical cuts he made, Matta-Clark seemed intent on opening up space to invite new possibilities of encounter.

Unlike his contemporaries in the 1960s and 1970s who so often used photography as a tool of documentation, Matta-Clark was equally, if not more, interested in the ways in which photography could reference the subjectivity of spatio-temporal experience. As Matta-Clark noted:

[There] is a type of space we all … have stored in memory: spaces that are detailed and precise, fragments generally, at all levels of reminiscence. And, of course, once you get into reminiscence, an infinite number of associations emerge. Memory seems to create a unique kind of space setting up an about-to-be-disintegrated level.20

Photography becomes the perfect medium through which to call up the mutability of memory while participating in the pretence of its stability. The ‘about-to-be-disintegrated level’ is exactly where Walls Paper operates – it is overtly subjective, fragile, fuzzy and imprecise.