‘Politics haunts the art of our time’. This blunt pronouncement opens critic Harold Rosenberg’s meditation on ‘Art of Bad Conscience’ – his column for the New Yorker published on 16 December 1967.1 American artists of 1967, along with the rest of the country, were grappling with the reality of an undeclared war in Southeast Asia that appeared ever more unjust, needlessly destructive and even foolhardy. The conduct of the war threatened the moral sanity of the generation called to fight and challenged the political purpose of the nation as a whole. This was a year of massive public protests in Washington, D.C. and throughout the country; in April, Martin Luther King, Jr, broadly recognised as a moral authority, delivered a lengthy sermon at Riverside Church, New York, titled ‘Declaration of Independence from the War in Vietnam’.2

From his position as an intellectual of the left and a prominent cultural critic, Rosenberg’s ‘Art of Bad Conscience’ addressed the intersection of art and politics at a time when politics was hard to ignore even by the temperamentally apolitical. He noted the limited potential – or, in most instances, the utter incapacity – of contemporary art to engage effectively in political protest. Times of social crisis demanded mass reaction rather than the views of individuals, Rosenberg argued, whereas a work of art offered no more than ‘the unique aesthetic statement’: ‘The most celebrated political painting of the century, Picasso’s Guernica [1937], has been of doubtful political consequence; its basic context is not the Spanish Civil War but Picasso and his imagery’.3 To the extent that aesthetic value and moral value coexist, it would seem that they do so in inverse proportion, as if refinement in art were a distraction from efficaciousness in politics.

Fig.1

Willem de Kooning

Women Singing II 1966

Oil on paper on canvas

914 x 610 mm

Tate T01178

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In the final sections of his essay Rosenberg evaluated attempts at aesthetic protest by specific groups during the several months before December 1967. He focused on two exhibitions in Manhattan: Angry Arts at the Loeb Student Center of New York University and Protest and Hope at the New School Art Center. He also discussed a conference in the Venezuelan capital Caracas that was sponsored by the Inter-American Foundation for the Arts, at which the divide between the political emphasis of the South Americans in attendance and the aesthetic emphasis of the North Americans was manifest.4 Preceding this ‘political’ section of the piece, as if to provide relief from instances of fraught aesthetic compromise to which the beginning and ending of his essay alluded, Rosenberg presented an account of Willem de Kooning’s new work at Knoedler Gallery in New York. The exhibition included Women Singing II 1966 (Tate T01178; fig.1), although Rosenberg wrote only in general terms rather than addressing individual paintings. To indicate the artist’s significance, he made an odd proposal: ‘If politics haunts post-war painting, de Kooning haunts the ghost’.5 He implied that the absence of political reference in de Kooning’s art countered the vaguely felt need of his peers to engage with politics. The artist was not oblivious to his historical context; yet the agonistic character of his process removed him from the political struggles surrounding him, which were of another order – neither higher nor lower, but different. The argument of ‘Art of Bad Conscience’ coordinated two incompatible aims: Rosenberg’s desire to support de Kooning, an old friend and art world ally, and his fidelity to his own sense of moral authority.

‘An ideologists’ man, but anti-ideological’

To haunt the ghost of politics with a practice of art would either compound the unease of the historical moment or gesture towards a liberating, humanistic response. Rosenberg approaches the notion that art functions best when it serves aesthetic needs, which are not necessarily related to social needs. In other words, by its nature art functions autonomously, addressing the problems of art. The majority of critics at work during the past few decades, especially of the academic variety, cringe at the thought of any human activity claiming autonomy or proceeding ‘by its nature’. Their intellectual formation (this author’s included) has instilled in them the belief that all human discourse is interrelated: it is social, political and subject to interminable intervention. Every condition affects and potentially explains another, not just in fictive historical narratives but in reality. Such a belief – for it is no more than a belief, a theory, a hypothesis – is as generative of myth as any other strong belief.6 But even for those who insist that autonomy in the cultural sphere is chimerical, there can be political benefit in promoting the myth and acting as if living it were a reality. It serves as the model of a freedom to be aspired to, if not gained – the freedom to make one’s own judgments, including moral judgments. Rosenberg had previously written that de Kooning possessed ‘genuine moral independence’ and ‘resisted every species of ideology’, and in an era that sets ‘every value of art in doubt, de Kooning … has felt free to doubt the doubt’.7 A sceptic’s distrust of absolutism might be as clouded by myth as any other rule of conduct. De Kooning observed no rules. Although sympathetic to anti-war protest during the 1960s, he refused to prejudge politically motivated actions, disapproving of those who dismissed the positions of the United States government without considering them fully.8

Haunting the ghost, doubting the doubt; a reader wonders whether such statements constitute rhetorical sleights of hand or effectively probe de Kooning’s intentions and accomplishments. Along the same lines, Rosenberg had stated that de Kooning ‘is an ideologists’ man, but anti-ideological’.9 Immersed in Marxist dialectical convention, the critic used – and perhaps overused – contradiction as an illuminating analytical device. But de Kooning too indulged in contradiction, spurred not by Marxist discourse but by a personal anarchism that led him to dismiss standard practices. In his later years he took to saying, ‘You have to change to stay the same’.10 To be true to himself, to ‘stay the same’, he needed to avoid regularity and fixed ideas – every indication of ideology, whether aesthetic or political. His non-Marxist (and hence suitably non-canonical) version of contradiction may be a corruption of the adage, ‘The more things change, the more they stay the same’, which has a direct origin in nineteenth-century literature and a remote one in the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes.11 De Kooning himself was an unreliable source. He sought no regularity in his conceptualisation, keeping his thought fluid, like a philosopher who never commits his ideas to writing but instead continues to think, which entails forever changing his mind and his philosophy – faithful to the process of thinking but not to its conceptualised ideas.12 The thinker gets nowhere, yet the results along the way are enlightening. Aimless, endless change was de Kooning’s desire, in art and elsewhere. ‘I didn’t want to pin it down at all’, he said in 1958, referring to his manner of painting: ‘I found out it was not my nature. I didn’t work with the idea of perfection, but to see how far one could go’.13 De Kooning’s nature was analogous to the putative nature of art. Where he could go, where art could go, would remain an unknown. Otherwise de Kooning would have a fixed aim, tantamount to an ideological value. He would be untrue to himself and, in his view, untrue to the freedom that a person should derive from either producing art or consuming it.

De Kooning was known for malapropisms as well as witticisms, and often the difference was indiscernible. Perhaps when he first referred to changing to stay the same, whenever that may have been, he meant to repeat the cliché (‘The more things change…’), but in the spontaneity of the moment the phrasing emerged scrambled.14 Like the fragments of his imagery that repeat by transference from one painting to another, de Kooning’s aberrant language has no fixed origin, existing only in its frequent repetitions. His version of the familiar adage seems to call for some kind of action rather than resignation with respect to the perpetual state of affairs, material or human. But the action of change for the sake of change has no clear outcome, if any outcome. De Kooning rarely left things as they were, even when complete. He was reluctant to finish works and went to extreme technical ends to keep his paint wet for revision, as he explained to a collector in 1969: ‘I am working for weeks and weeks on end on a large picture and have to keep the paint wet so that I can change it over and over, I mean, do the same thing over and over’ – change with the result of staying the same.15 He preserved the record of his process by producing variations of a single composition and generating imprints of an image as it was being developed. He could move backward as well as forward. He merely sought movement: to change. Signed and exhibited paintings like Women Singing II may have an unfinished look but lack a typical rhetoric of the ‘unfinished’, such as artfully distributed drips and rhythmically spaced bare spots. ‘De Kooning’, Rosenberg wrote in 1963, ‘offered the New York art world the example of an artist who dared, when necessary, to endure unalleviated confusion’.16

Popular sources and political effects

Several years later, at the start of ‘Art of Bad Conscience’, Rosenberg issued a warning, as relevant now as then. It hinged on differentiating ‘art history’ as the record of art as a practice from ‘history’ as the record of social organisation and politics as a practice:

By all evidence, art history is at odds with history. And the helplessness of art when it crosses over into the political arena increases year by year with the expansion of the mass media; the more advanced the communications system the less the impact of the unique aesthetic statement … Nor can painting and sculpture augment their powers by appropriating the style of the popular arts, for the power of the media lies not in their style … but in their mechanisms of production and distribution.17

The mass media have recourse to standardised repetition – a flawless edition of millions. An ideological message becomes ingrained in the minds of its target audience, converted to a single mass mind; the mentality of the consumer of media is mass mentality. An art like de Kooning’s, for which the only consistent repetition is the factor of change, may appear ideologically impotent. But even in Rosenberg’s time, some artists, recognising their handicap in the ideological field, were becoming involved with systems of distribution. A prime example was Joseph Beuys and those affiliated with the loose organisation of artists known as Fluxus. In Japan, Genpei Akasegawa used the exchange of currency to further social protest, while in Chile, Guillermo Deisler and others used the postal system to disseminate information. In New York, Douglas Davis and Richard Serra created works for public broadcast on television. In our own time, what Rosenberg thought could not profitably become the province of serious artists, ‘the mechanisms of production and distribution’, occupies a prominent position in the range of contemporary practice: that of Cildo Meireles, Charles Simonds, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Sharon Hayes, Francis Alÿs, Theaster Gates and many others.

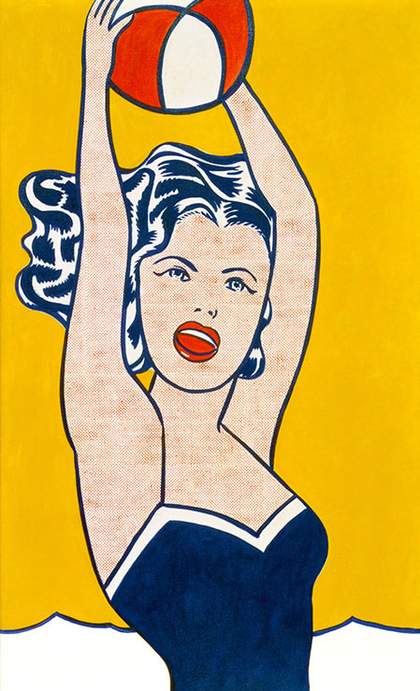

Fig.2

Roy Lichtenstein

Girl with Ball 1961

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Listing exceptions to the rule that Rosenberg advanced establishes a more complete record, but is irrelevant to the local context of the critic’s concern. He invoked the issue of production and distribution not only to articulate the vast difference he perceived between media arts and fine arts, but also to indicate the situation of the American pop art of the 1960s. A wholesale appropriation of popular imagery appeared in works by Roy Lichtenstein (see, for example, Girl with Ball 1961; fig.2), Andy Warhol and James Rosenquist – three artists featured in The New Realists exhibition of November 1962 at Sidney Janis Gallery, de Kooning’s dealer at the time. Their style was at odds with the roughshod allusions to the same imagery that had been a feature of the older painter’s art since the 1940s, and to some extent even in the 1920s. Like the emergent pop artists, de Kooning had experience as a commercial illustrator. In his work for fine art exhibition, the material qualities of paint and charcoal affected a viewer’s perception directly, but less so did the representational image; its non-normative distortions, sense of incompletion and (as Rosenberg noted) aura of ‘unalleviated confusion’ interfered with the recognition of a theme or message, if any was being conveyed.18 Pop art, to the contrary, shared a degree of directness with the presentation of ideological propaganda, where the manner of depiction allowed immediate access to the full identification of whatever was represented. Responding to Lichtenstein’s art at the time of the Sidney Janis show, critic Leo Steinberg articulated the perceptual challenge (or its lack) associated with the new style: ‘[It has] pushed subject matter to such prominence that formal or aesthetic considerations are temporarily masked out. Our eyes will have to grow accustomed again to … the presence of subject matter absolutely at one with the form’.19 The complete dominance of the representational subject was rendering aesthetic analysis of material and compositional aspects difficult to conduct. In 1967, Rosenberg observed accordingly that ‘derivations from Pop Art [have] proved most available for retooling to serve political ends’.20 With respect to the presentation of images, the style of pop art – not necessarily the actual practice, which leaned in other directions – offered fine artists their best chance to make compelling political statements.

Already during the nineteenth century, artists had been ‘appropriating the style of the popular arts’, to use Rosenberg’s phrasing.21 The strategy was ‘modernist’, but an old one: think of the graphic simplification of figures in the art of Georges Seurat (see, for example, Parade de cirque 1887–8, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) or the posters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, followed by the fruitful confrontations with commercial imagery in practices as diverse as those of Picasso and Stuart Davis. To a great extent, de Kooning belongs within this lineage. Critic and de Kooning supporter Thomas Hess noted the before-its-time pop character of the offset imagery – ‘columns of type … illustrations of bathing beauties and gangsters’ – that remained visible in some of de Kooning’s compositions of the 1950s. The effect appeared when the artist used sheets of newspaper to mask areas of wet paint; the newsprint ink would transfer to the painting, with its words legible and its images whole. Today, both the look and the process might recall Robert Rauschenberg’s use of solvents for transfer of print media and his abundant use of photosensitive silkscreen transfer; but de Kooning’s version ‘preceded [Rauschenberg] by about a decade’.22 As for the examples of pop art of the early 1960s, Hess argued backhandedly that they drew their inspiration from the public that they should have been inspiring. The works had a political effect, but one that the critic dismissed, just as Rosenberg would have as well: ‘Pop Art is political in that it keeps urging the belief that everything is rosy; even our ignominy, the electric chair, gets a quaint cosmetic look’.23 Numerous contemporaries, both artists and critics, appreciated the technical qualities of pop art but demeaned its effect as mere ‘fun’.24 To most viewers, de Kooning was more confusion than fun – a point in favour of his potential seriousness.

Thinking and feeling in Women Singing II

Pop art provided a catalyst for Rosenberg to link his analysis of de Kooning to his critique of protest art. Along with similar examples, Women Singing II, an oil on paper work mounted on canvas that was made in the politically tense year of 1966, existed at the centre of current debate, as Rosenberg, Steinberg, Hess and others conceived it. Significantly, its subject matter was ‘pop’ but not its technique. The painting is typical of de Kooning’s output after he moved from Manhattan in 1963 and began to work at the studio he designed for himself in the village of Springs, East Hampton, on the south fork of eastern Long Island, where construction was completed in 1964. Many of his Manhattan studio paintings have a gritty appearance; Hess described their women as ‘very much a part of the city’.25 The works from the Long Island studio tend to be lighter, airier and decidedly fluid. Singing, as in a performance, connotes an indoor environment, yet the palette of Women Singing II evokes the full daylight of Long Island beaches – rose-orange (the flesh of bathers), turquoise (the sea) and golden yellow (the sun and sand). De Kooning’s colour, however, is never formulaic; he took full advantage of the capacity of wet oil paint to generate off-colour or assonant mixtures. With regard to colour, texture and other effects, he enjoyed allowing the results of his spontaneity to surprise him: ‘I see things I like, I don’t fight them’.26

Fig.3

Willem de Kooning

Women Singing II 1966, detail of lower right quadrant

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In a study of the new Long Island works, Hess included a full-page reproduction of Women Singing II, albeit in black and white.27 He prepared his essay in consultation with the artist and in conjunction with the exhibition at Knoedler Gallery in November 1967, a focus, as noted, of Rosenberg’s ‘Art of Bad Conscience’. Women Singing II is very much a drawn painting, with many of its brushed lines extending across the slick paper surface, metonymically signifying de Kooning’s delight in their fluidity; his gestures seem only barely constrained by a sense that the two human figures should be contained within a pictorial rectangle. No extra space surrounds them – they have no environment, no perspective, no atmosphere. Hair hits the upper margin; elbows and hands hit the side margins; legs and shoes hit the bottom margin. De Kooning was painting two bodies, not a scene of singing and dancing. In the lower right corner, two pairs of flesh-coloured ‘legs’ descend from a single, loosely indicated torso; the four strokes compete for the privilege of describing the figure’s lower anatomy (see fig.3 for a detail). Nothing inhibited the artist from leaving supernumerary limbs visible; if extras rendered the totality more engaging, then so be it. He was creating a painting, neither the image of physical beauty nor the representation of a monster. Among the many meanings that figuration held for him, it served as a procedural beginning for his art as well as something specific to hold on to as his departures from this visual and conceptual template accumulated. When asked about the importance of establishing a representational identity for a painting, he replied: ‘The very fact that it had a word connected with it – “figure of a woman” – made it more precise’.28 At the termination of one of the strokes that indicate legs in Women Singing II, a graphic representation of a high-heeled shoe remains visible as an element of underdrawing, part of the initial configuration as de Kooning imagined it, whether retrieved from his stock of remembered observations or transferred from an allied configuration. The effect of multiple limbs suggests movement in the ‘woman’ as well as in de Kooning’s process of painting – and in the thinking and seeing that his painting was reflecting. The image was changing, and he was changing.

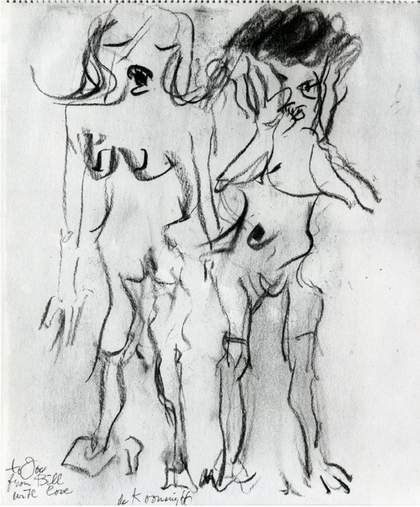

Fig.4

Willem de Kooning

Untitled 1966

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

De Kooning most likely derived his imagery of two women from small drawings sketched rapidly. He sometimes composed such drawings from the memory of an observation, and would occasionally execute them left-handed or with eyes closed. He insisted on challenging his skill. Often he drew from the moving image of evening television. Women seen clothed, perhaps scantily according to the fashion of the time, could become nudes in memory – nudes in high-heeled shoes, as in the figure on the left in an untitled charcoal drawing of 1966 (fig.4). In 1965, he referred to posing nude models in high-heeled shoes – with the fantasy realised, no imaginative memory would be required. The shoes, he said, would stretch the image upward; the device would produce an effect of elongation analogous to turning the depiction of a reclining figure vertically.29 Here de Kooning’s fascination with women’s bodies, clothing and characteristic movements (hardly misogyny or sexism from his perspective) merged with his absorption in the process of drawing and painting.30 Susan Brockman, his companion during the mid-1960s, observed him bending and stretching his body as he drew from memory, enacting the feeling of the drawing itself, and through the drawing, the body of another (or vice versa).31 The artist was at that moment the body that he drew.

Rosenberg listed many of de Kooning’s techniques and effects, as did Hess.32 Both critics were in close communication with the artist. Hess matched Rosenberg’s political emphasis with the philosophical and psychological implications of what de Kooning was about: ‘The mind is not a mansion divided into rooms, some labeled Emotions, and others Ideas’ – in his painting, thinking and feeling integrated, or rather, never diverged.33 Hence Rosenberg’s stress on de Kooning in action, as opposed to executing a concept or plan: ‘For an interval, painting and the painter are one in the action on the canvas. But only for an interval, and in the inevitable dispersion both art and the artist are nothing’.34 For an artist seemingly lacking an external concept, the question of the completion of any given image became, for critics like Rosenberg and Hess, irrelevant to its cultural value.

Fig.5

Willem de Kooning

Women Singing II 1966, detail of centre right section

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

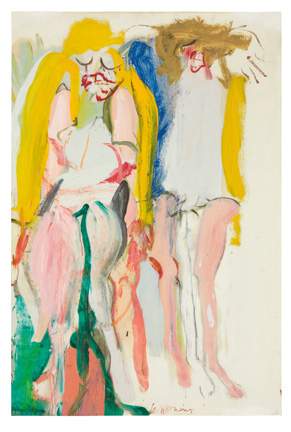

Fig.6

Willem de Kooning

Singing Women 1966

Oil on paper on masonite

914 x 610 mm

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fig.7

Willem de Kooning

Women Singing I 1966

Oil on paper on board

914 x 609 mm

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

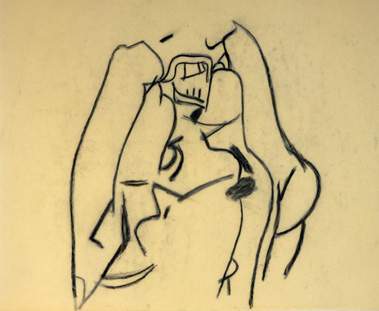

Fig.8

Willem de Kooning

Untitled c.1966–7

Private collection

© 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Often the imprint or tracing of a fragment of a sizable image, or multiple tracings of small images, would constitute a composition in the making within a new format. De Kooning preferred not to project or scale up a form from one instantiation to the next; direct transfer by imprinting or tracing worked well for him. Customarily, he used the daily New York Times for blotting and imprinting but occasionally employed other types of paper as well; the torso and pelvic area of the figure to the right in Women Singing II reveals a characteristic textural pattern of kitchen towelling (fig.5). De Kooning may have enlisted tracings from Singing Women 1966 (fig.6) or Women Singing I 1966 (fig.7) to establish elements of linear armature for one or both of the figures in Women Singing II, but a sequence of production is hard to determine since the three paintings are likely to have been in progress simultaneously. An untitled charcoal drawing on vellum is an example of what appears to be a tracing from a stage of Singing Women – the type of drawing used to transfer a linear configuration from one surface in progress to another (see Untitled c.1966–7; fig.8). Furthermore, in any composition of two figures, one may have generated the basis of the other internally, through the intermediary of a paper tracing or monotype transfer.35

The fact that the figure on the left in Women Singing II is more defined than

its neighbour indicates the possibility of an order or hierarchy of transfer.

Political spontaneity

Just as de Kooning would blot a wet surface and imprint onto another, he transferred his sense of impulsive gesture from small drawings completed rapidly to relatively large paintings over which he laboured for lengthy periods. A painting might be worked and reworked excessively, yet each studio session consisted of a sequence of spontaneities – the changes that kept de Kooning true to himself. As the process of linear and colouristic manipulation developed, a figure could shift from the seated position preferred by the artist, to a reclining position, to a standing position: ‘A girl sits there with her legs crossed’, he explained; ‘I get a feeling about her … and try to put it down. [My] drawings are fast’.36 Yet many of the drawings, like the paintings, incorporated numerous changes. The disposition of hips and legs in Women Singing II, especially for the left figure, is closest to that of a seated, cross-legged pose, which the artist may have whimsically transformed into dancing and singing with upraised arms. The ‘arms’ appear independent of any initial linear foundation; these fluid strokes of pinkish orange are flairs into space that could conceivably turn in any direction. As De Kooning said: ‘That’s what fascinates me – to make something I can never be sure of, and no one else can either … That’s the way art is’.37 From this continuing situation of immanent change, the absence of a final decision or solution, Rosenberg perceived a political implication: ‘Under the conditions of ideological pressure of the past forty years, spontaneity itself is a quasi-political attitude – one condemned by Lenin, outlawed in totalitarian countries, and repugnant to conformists and programmers’.38 The communist regimes of the East were totalitarian; the capitalist regimes of the West were conformist. Spontaneity, inherently anti-ideological, became a subversive force around the globe, a threat to every over-organised society. For Rosenberg, de Kooning embodied that threat.

In 1967, a year of increasing protest, Rosenberg noted that all too often painters who enlisted their art in a political cause ‘dashed [the works] off without regard for craft standards, as if in a rush to return to the serious business of making paintings and sculptures’.39 The modifier ‘serious’ is ironic because, given the context of the civil rights movement and the war in Vietnam, politics had become of far greater import in everyday American life than had art. Yet we can regard Rosenberg’s use of the word ‘serious’ as hardly ironic at all: no matter the context, art is a more serious (more enduring) practice than politics. In this respect, de Kooning ‘haunts the ghost’ with spontaneity, all-inclusiveness and perpetual change. Rosenberg brought his ‘Art of Bad Conscience’ to a stirring conclusion:

Art cannot do much for politics … But responding to political struggles can do much for art. Art always borrows its seriousness from values – religious, romantic, scientific – it fails to live up to. The formal interests of the artist and his delight in his craft set him apart from genuine holiness, love, or research. Yet when logic induces the artist to consider art capable of renewing itself by its own means he finds himself in a blind alley. Art today needs political consciousness in order to free itself from the frivolity of continual insurrections confined to art galleries and museums.40

Those resistant to the charms of pop art regarded it as one of the in-house ‘insurrections’ often justified only in the negative as decidedly not abstract expressionism.41 Whatever the degree of his ‘political consciousness’, de Kooning fulfilled at least half of Rosenberg’s cultural remedy by refusing to engage in art world jockeying or the ‘dogmas of art history’.42 His sources were eclectic, from the old masters, to the prototypical modernist Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), to billboard advertising, to comic strips. Conceivably, de Kooning was pop and abstract expressionist. He claimed no avant-garde status. Instead, he signified ‘the individual as he is [who] pits himself against all systems’, both aesthetic and political.43 It was in this sense that de Kooning haunted the ghost of politics, for the practice of politics, because it formulates and advocates a partisan position for all, fails if it remains no more than an individual effort. De Kooning’s Women Singing II, along with his related works of the 1960s, exemplified successful individual effort directed towards nothing definitive – neither towards garnering approval nor towards seducing converts. As he worked from painting to painting, recasting elements of one image as elements of another, none achieved permanent status. De Kooning occupied no position.

Social historians and other contextualists view art as a reflection of politics, which does not bode well for art. To reverse the mirroring and invert the order: politics benefits when it reflects art. Haunted by the thoughts, emotions and doubts generated by art produced in exploratory isolation – haunted by de Kooning – political argument might edge towards the fluidity of painting like his. A reinvigorated politics would avoid dogma by adjusting to an ever-changing context, getting somewhere but with no insistence that it remain there. It would escape rigidified ideologies, or at least lighten the ideological burden that inhibits responsive change. With his variations on ‘pop’ icons – from pin-ups, to performers, to urbanites, to suburbanites – de Kooning was keenly attentive to the situation of his American culture. But he regarded the social and political context, the so-called reality of his society, as no more stable or directive than the configurations of his paintings. What we recognise as iconic is as transient as what sparks no recognition at all. This realisation, or belief, liberated de Kooning’s art from all contextual constraint.