Fig.1

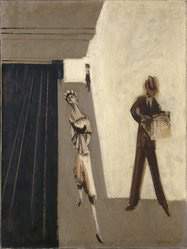

Bernard Perlin

Orthodox Boys 1948

Tate N05956

In Bernard Perlin’s Orthodox Boys 1948 (Tate N05956; fig.1), the two Jewish teenagers waiting for a train in New York’s Canal Street subway station appear apprehensive, yet stoic and still, as they worriedly glance toward the dark tracks on the lower left, and perhaps at some ominous threat. Amplifying the picture’s menacing mood, Perlin has painted the boys as sharp, solid forms and posed them against a large green wall (likely the back of a newspaper stand) that is covered in a writhing mass of graffiti: names (‘Jeff’, ‘Frankie’, ‘Phil’, ‘Abe’, ‘Joel’, ‘Bernstein’), dates, initials, slang phrases, racial slurs, caricatures and symbols, all vigorously marked on the surface in multicoloured chalks and inks.

Jews, trains and a dense wall of names: the iconography that Perlin selected for his unsettling 1948 painting could not more clearly evoke Nazi Germany’s genocidal anti-Semitism, and the horrors of a Holocaust in which millions of European Jews were isolated, transported, imprisoned and annihilated with a murderous fanaticism that included obsessively listing the names of victims. Anti-Semitism was not, of course, confined to Europe, nor did it end with the Allied defeat of the Third Reich in May 1945. Positioning the anxious bodies of Orthodox Boys against a frenzied wall of distracting and unnerving graffiti, Perlin addressed the fraught state of being Jewish in post-war America.

Perlin painted in a representational style throughout his career: as a social realist in the New Deal era of the 1930s and as a magic realist in a post-war climate dominated by notions of mainstream political consensus and anti-Communist containment, and critical preferences for abstract and non-representational art. He was also queer, part of a circle of artists that included painters Paul Cadmus and Jared French, photographer George Platt Lynes and critic Lincoln Kirstein.1 Jewish, queer and committed to a critically unpopular post-war art style, Perlin’s ethnic, sexual and artistic marginality heightened his particular sensitivity to issues of power and vulnerability: the general theme of Orthodox Boys.

This essay looks at various sources for Perlin’s painting, from modes of propaganda employed during the Second World War when he worked as a poster artist for the US government, to the nature and visual evidence of youth gangs, graffiti and subways in 1940s New York. It further examines Perlin’s perspectives as a Jew and a modern artist in a post-war moment when critics and curators tended to ignore or downplay religious references, especially when they surfaced as markers of aesthetic intentionality. As the title and subjects of Perlin’s 1948 painting suggest, different kinds of orthodoxy – from religious ideologies to modern art styles – competed for attention and authority in post-war America.

The Second World War, propaganda and anti-Semitism

In September 1939, shortly after Germany invaded Poland, Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, dictated a memo demanding more Nazi ‘wall newspapers’, or posters. ‘Everywhere in the Reich where there is dense traffic, poster boards of the Nazi party are to be set up’, Goebbels insisted. ‘All means of transport (railroad, streetcars, subways, buses, and so on) will receive posters, which are to be placed in every wagon, on the train platforms, in the ticket windows, as well as in the entrances to these forms of public transport’ (fig.2). As historian Jeffrey Herf explains, ubiquitous political posters – named Parole der Woche, distributed by the thousands every week from 1936 to 1945 and strategically displayed all over Germany – were a primary means of asserting Nazi ideology and, in particular, radical anti-Semitism.2

Fig.2

Julien Bryan

A group of young German boys view Der Stuermer, Die Woche and other propaganda posters that are posted on a fence in Berlin, 1937

Julien Bryan Archive, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

© Julien Bryan

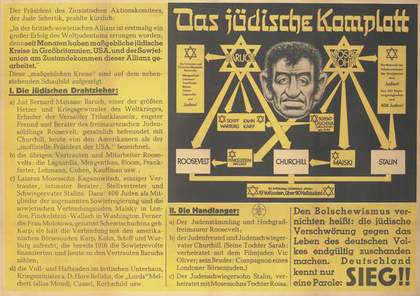

Fig.3

Parole der Woche, no.50 1941

Nazi German political poster headlined ‘The Jewish Plot’ featuring a racist caricature of American financier and statesman Bernard Maruch and a ‘genealogical’ chart linking him to ‘Jewish agitators’ Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin

Imperial War Museum, Manchester

© German Government

Featuring bold type, bright colours and a gripping blend of text and image, these large-format Nazi propaganda posters were visually intrusive, literally commanding audience attention to their paranoid narratives about, especially, the ‘Jewish Enemy’ (fig.3). Blatantly reversing cause and effect with a wad of contradictory rationalisations, Nazi propaganda accused Jews of plotting an international anti-German conspiracy, blamed them for starting and escalating the Second World War, and depicted Jews as dangerous adversaries that must be exterminated. Germany’s foes were similarly indicted as weak nations led by warmongering Jews. A 1942 poster depicting US President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the company of American Jews was captioned ‘They will stop laughing’, a deliberate reference to a speech in which Hitler stated: ‘The Jews in Germany once laughed about my prophecies. I don’t know if they are laughing today or if the laughter has already gone out of them. I can promise only one thing. They will stop laughing everywhere.’3

Studying in Poland on an art scholarship in 1938 and also traveling in Germany, Perlin recounted in his diaries the ubiquity of Nazi propaganda and European anti-Semitism. A few years later, working in the Graphics Division of the US Office of War Information (OWI) from 1942 to 1943, he became further conversant with the visual and narrative projections of Parole der Woche and similar Nazi tools. The first chapter of Frank Capra’s widely watched Why We Fight, for example, a seven-part documentary commissioned by the OWI that included footage from Nazi propaganda films like Leni Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will 1935, scenes of German school children being taught that Hitler was ‘the voice of God’, and Nazi political posters promoting Aryan supremacy, was released in May 1942.4

The OWI’s Graphics Division, which produced over 200,000 poster designs, was similarly focused on mobilising Americans: on explaining why the nation was at war and urging citizen support with patriotic appeals to freedom, unity and home front productivity. OWI posters were further framed by expectations of visual ubiquity. As one OWI staffer stated in 1942: ‘We want to see posters on fences, on the walls of buildings, on village greens, on boards in front of the City Hall and the Post Office … shouting at people from unexpected places with all the urgency which this war demands.’ As another put it: ‘People should wake up to find a visual message everywhere, like new snow – every man, woman and child should be reached and moved by the message.’5

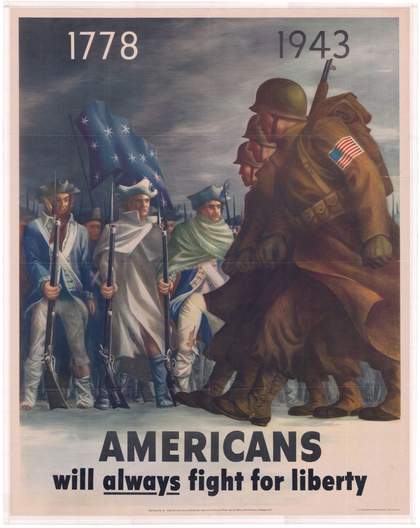

Fig.4

Bernard Perlin

Americans Will Always Fight for Liberty 1943

Office of War Information poster

Office of War Information World War II Papers, Military Collection, State Archives of North Carolina

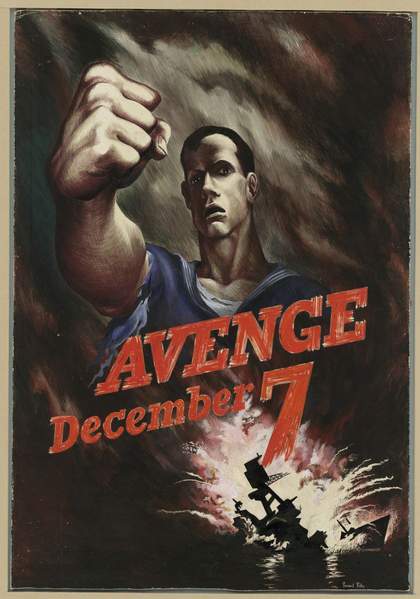

Fig.5

Bernard Perlin

Avenge December 7 1942

Office of War Information poster

National Archives, College Park, Maryland

Rejected from military service for his professed homosexuality, Perlin was schooled in the lessons of US propaganda at the OWI, where he joined American artists including Ben Shahn and Henry Koerner and designed posters such as Americans Will Always Fight for Liberty 1943 (fig.4).6 Juxtaposing a motley band of stalwart American Revolutionary soldiers from 1778 with an equally determined battalion from 1943, the ‘message’ of Perlin’s poster was enduring American unity – one of ‘six basic propaganda themes’ approved by the OWI.7 While Shahn’s chilling representations of Nazi terrorism in posters like This is Nazi Brutality and We French Workers Warn You … Defeat Means Slavery, Starvation, Death (both 1942) were deemed too ‘violent’ by OWI staff, Perlin attended to the morale-building aims of US wartime propaganda.8 Posters like Avenge December 7 1942 (fig.5) and Let ‘Em Have It 1943 depicted aggressively strong-armed Americans taking action against the enemy. Yet like Shahn, Perlin did not shrink from depicting American difference: notably, the figure in Avenge December 7, rising Phoenix-like out of the smoky catastrophe of Pearl Harbor and thrusting his fist into the viewer’s field of vision, was not Aryan.

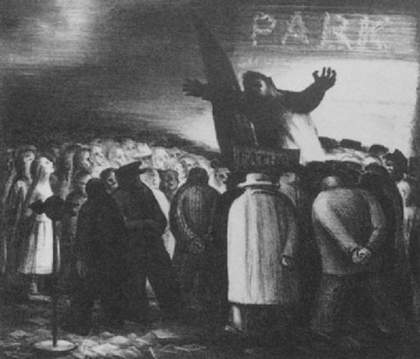

Perlin’s interests in American pluralism, anti-Semitism and the visual power of propaganda surfaced earlier, in his 1930s social realist art. His 1938 lithograph Father Coughlin Speaking, for instance, depicted the demagogic ‘Radio Priest’ gesticulating in front of an admiring and sinister crowd (fig.6). Living in Brooklyn in the late 1930s, Perlin was certainly aware of Coughlin’s huge appeal: his unabashedly anti-Semitic and pro-Fascist radio show The Hour of Power reached more than forty million listeners per week, and his odious Christian Front, which boycotted Jewish businesses and held mass rallies inciting anti-Semitic violence, was first organised in Brooklyn in 1938.9 Perlin’s design for a mural for the post office of South Orange, New Jersey, commissioned in 1939 by the US Treasury Department’s Section of Fine Arts, countered Coughlin’s bigoted notions of an all-white Aryan nation with scenes of racial and ethnic diversity in small-town America.

Fig.6

Bernard Perlin

Father Coughlin Speaking 1938

© Bernard Perlin

Coughlin’s menacing popularity was no anomaly: anti-Semitism was rampant in the United States both before and during the Second World War. Perlin personally experienced it, noting in his diaries a particularly disturbing encounter on a New York subway in 1936 in which two older women called him a ‘dirty Jew kike’ and insulted him with homophobic slurs.10 Jews were denied full access to higher education, barred from certain jobs, discriminated against in housing and widely disliked. A 1938 Gallup poll found that 50% of Americans held a ‘low-opinion’ of Jews; a 1939 Roper poll reported that 53% believed that ‘Jews are different and should be restricted’; and a 1946 survey showed that 64% of respondents reported hearing recent ‘criticism or talk against the Jews’.11 In New York – the mid-century locale of Perlin’s Orthodox Boys and home to about two million Jews (one third of all Jews in the US) – anti-Semitic violence was ‘part of everyday life’, writes historian Eva-Maria Ziege. Jewish cemeteries and synagogues were regularly defiled with graffiti and swastikas and Jewish school children frequently assaulted by youth gangs.12

Anti-Semitism only began to wane in the US later in the 1940s, when government measures like the G.I. Bill for veteran servicemen and federally funded home loan programmes generated educational, occupational and housing opportunities that allowed for Jewish social and geographical mobility, and encouraged mainstream American assimilation. In 1948, when Perlin painted Orthodox Boys, US Congress passed legislation granting entry to 400,000 DPs (‘displaced persons’, or refugees), of whom 20% were Jewish. That same year, the Jewish State of Israel was proclaimed in Palestine.

While painted at this moment of significant change, Orthodox Boys is neither hopeful nor aspirational: the Jewish students in the centre of the canvas are anxious, even frightened. Although Perlin marshalled masculine mettle and fortitude in OWI posters like Avenge December 7, the figures in Orthodox Boys seem frozen, unable to move. Importantly, they are solid, physical bodies: they may be fearful but they hold their ground. Refusing the exterminating mandate of Nazi German and American anti-Semitism, Perlin cast the boys as resolute symbols of Jewish endurance. Yet he also showed them isolated and alone in an ominous underground space: grim, worried and still. The graffiti surrounding them is the most animated feature of Perlin’s painting, and as such takes on special meaning, as discussed further in Aaron Rosen’s essay ‘The Painting’.13

Urgently rendered, and occupying public wall space where wartime propaganda posters might once have commanded attention, Perlin’s mass of words and images may be seen as a memorial to Europe’s murdered Jews: dense with the names of the dead, dotted with the symbols – such as swastikas – of those who killed them. Names play dual roles in Perlin’s painting, referencing the Nazis’ obsessive cataloguing of their victims, and constituting familiar, recognisable signs of real people. Naming is an act of claiming, an assertion of inclusion: to be named is to be acknowledged.14 Standing in front of this thicket of named individuals, the two subjects of Orthodox Boys stoically bear witness to their murder and loss. Their visibly worried expressions, however, suggest a persistent mood of menace, a foreboding of new threats.

Gangs, graffiti, subways and post-war abstract art

Fig.7

Bernard Perlin

Cover illustration, Saturday Review of Literature, 8 May 1943

Perlin’s particular focus on two Jewish teenagers positioned Orthodox Boys in the orbit of The Amboy Dukes: Irving Shulman’s popular 1947 novel about Jewish juvenile delinquents in Brooklyn. Set in 1944, Shulman’s gritty coming-of-age story centres on Frank Goldfarb, a disaffected sixteen-year-old who rejects his parents’ goals and values (both work overtime shifts in local munitions factories so that Frank and his sister can ‘have a better life’) and seeks acceptance in a violent Jewish youth gang (the Amboy Dukes).15 In one scene, gang members molest a woman on a crowded subway train; in another, a twelve-year-old girl is gang-raped at a school dance. Defending their turf and identity, the Dukes repeatedly get in fights with other, differently configured gangs: early in the novel, Frank and his pals assault some Puerto Rican teens who have ventured into the neighbourhood, accusing them of ‘chalking up shuls’ (vandalising synagogues) with swastikas and anti-Jewish slurs.16 It is interesting to note that the name chalked directly above the head of the young Jewish boy on the left side of Perlin’s painting is ‘Frankie’.

Selling over five million copies, Shulman’s novel gave rise to a thriving new genre of ‘J.D. [juvenile delinquent] lit’, whose gripping narratives about gangs, switchblades, zip guns, rumbles and alienated urban youth fed the flames of a post-war panic about teenage crime and deviance.17 Priced at twenty-five cents, The Amboy Dukes and similar mass-market paperbacks were easily purchased from racks at drugstores, train and bus stations, and subway newsstands like the one that may be on the other side of the graffiti-filled wall in Orthodox Boys. Perlin’s commercial art might have even shared space on these kiosks with Shulman’s novel, especially since Perlin worked as a commercial illustrator for various magazines and journals throughout the 1940s and 1950s. The cover of the 8 May 1943 issue of the Saturday Review of Literature, for example, featured Perlin’s illustration for Stephen Vincent Benét’s poem ‘They Burned the Books’, written on the ninth anniversary of the Nazi purge of ‘un-German’ literature in 1933. Perlin’s sketch consisted of a Nazi dagger – identified by the swastika on its handle – piercing several books, its blade coated in blood (fig.7).

Fig.8

Mark Rothko

Subway 1939

1016 x 765 mm

Brooklyn Museum, New York

© Mark Rothko

Subways and graffiti attracted the attention of multiple artists in the 1930s and 1940s. Mark Rothko painted a variety of subway scenes in the later 1930s, including pictures of commuters waiting on platforms, reading newspapers and impatiently scanning the tracks for arriving trains (see, for instance, Subway 1939; fig.8). In 1946 Stanley Kubrick – who worked for Look magazine before becoming a film director – shot hundreds of photos for a proposed article titled ‘Life and Love on the New York City Subway’, several showing passengers waiting for trains at Canal Street (fig.9).18 While both Rothko and Kubrick’s pictures captured the claustrophobic mood of New York’s subways, none showed any evidence of graffiti.

That subject was partly the purview of street photographer Helen Levitt, whose snapshots of working class children in various New York neighbourhoods from the late 1930s to the 1940s included pictures of them making chalk drawings and playing in vacant lots marked with occasional names and scribbles (see Untitled 1942; fig.10). As Levitt’s friend James Agee observed in a 1939 essay, ‘All over the city on streets and walks and walls the children, and the other true primitives of the race have established ancient, essential, and ephemeral forms of art, have set forth in chalk and crayon the names and images of their pride, love, preying, scorn, desire.’19

Fig.9

Stanley Kubrick

Woman on the Canal Street Subway Platform, from the proposed Look article ‘Life and Love on the New York Subway’, 1946

From the Collections of the Museum of the City of New York

© Stanley Kubrick

Fig.10

Helen Levitt

Untitled 1942

© Helen Levitt

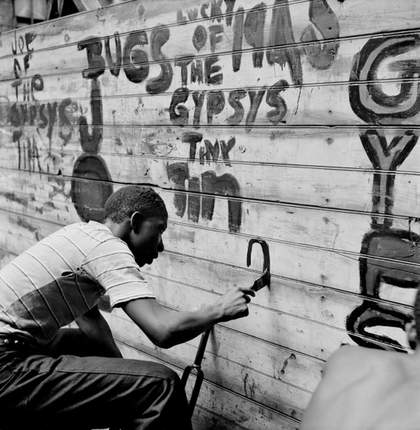

Agee’s statement was a little effusive: graffiti was infrequent in mid-century New York, and was mainly made by street kids and youth gangs to mark their turf, or to mark up sacred Jewish spaces as is suggested in The Amboy Dukes. Perlin might allude to these youth gang signatures by including the names ‘Irish Falcons’, ‘Brooklyn Busters’ and ‘The Mightie Atoms’ on the graffiti wall backdrop in Orthodox Boys. In photos taken for his 1948 Life magazine article ‘Harlem Gang Leader’, Gordon Parks shot pictures of seventeen-year-old Leonard ‘Red’ Jackson hand-painting the names of his gang The Midtowners on the side of a wooden wall (fig.11).20 It was not until the invention of spray paint cans (in 1949) and permanent (‘magic’) markers (1952), both of which only gained widespread popularity in the 1960s, that the city’s public spaces became increasingly tagged and covered in graffiti.21

The graffiti wall that Perlin painted in Orthodox Boys was, then, highly symbolic: a surface of names recalling the millions murdered in the Holocaust; an informed popular culture reference to post-war youth culture; and an edgy, animated prop mimicking the new styles of non-objective and abstract art that post-war critics and curators were eagerly promoting. The figures he posed in front of this multi-layered backdrop symbolised post-war worries about rebellious teenagers and persistent strains of anti-Semitism. They also embodied Perlin’s personal anxieties about the seemingly marginal state of the realist and representational pictures he painted.

Fig.11

Gordon Parks

Gang Member Graffitis a Wall, Harlem, New York, 1948 1948

The Gordon Parks Foundation, Pleasantville

© Gordon Parks

In 1948, for example, influential critic Clement Greenberg proclaimed: ‘the level of American art has risen in the last five years, with the emergence of new talents so full of energy and content as Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, David Smith … the main premises of western art have at last migrated to the United States, along with the center of gravity of industrial production and political power.’22 That same year, the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, organised by New York’s Museum of Modern Art, included abstract expressionist artists such as Gorky and Rothko, as well as Mark Tobey, whose dynamic ‘white writing’ style of all-over abstract brushwork was, Greenberg had earlier observed, ‘one of the few original contributions to contemporary American painting’. Post-war American modernism, Greenberg insisted, should be ‘uninflated by illegitimate content – no religion or mysticism or political certainties’.23 By the 1950s, modern painting in the United States would be largely dominated by abstract styles that critics and curators championed as exceptionally and distinctively American, much like the post-war nation itself.

Stylistically referencing Tobey’s ‘white writing’,24 Perlin’s graffiti wall simultaneously intimated narrow post-war notions of the ‘legitimate’ terms of modern American art: dogmatic decrees – especially in their refusal of ‘religion’ and insistence on certain styles or looks – ominously akin to those pronounced by fascist political regimes just a few years earlier. Savvy about the historical precedents and current stakes of marginalisation – whether religious, social, sexual or cultural – Perlin imbued Orthodox Boys with a palpable and familiar sense of anxiety.