Gimmick or no, these portraits (the first work by Larry Rivers to be shown in Paris) are superbly painted. Rivers is the only famous member of the ‘New York School’ who has never abandoned figurative painting, and the result proves that there need be no conflict between recognizable form and the adventurous spirit of abstraction.

John Ashbery (1962)1

It can strike us as a paradox that Larry Rivers should naturally be described as a member of the New York School of abstract expressionism when he was not an abstract painter. The difficulty of assigning Rivers to a suitable art movement was encapsulated in 1960 by the art critic Betty Kaufman’s formula, when she called Rivers ‘an action painter manqué’, suggesting his failure to live up to that label.2 Three years later, Warhol would add to the ambiguity of Rivers’s position by proclaiming him ‘the daddy of “Pop Art”’.3

The plurality of influence and suggestion in Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson 1961 (Tate T00522) marks Larry Rivers’s simultaneous engagement with, and deflection of, movements in the twentieth-century art world. Elements of abstract expressionism, figurative portraiture and pop combine on this relatively small canvas in a non-committal manner consistent with the way Rivers operated in the studio and otherwise. There are obvious nods to abstract expressionism in Parts of the Face – patternless swathes of colour, contrasting paint allowed to drip down the canvas – but the rigidly stencilled text and central figure seem to relegate the abstract elements to the level of background or staging. Those stencilled French words, in turn, flirt with pop preoccupations such as mass reproduction, advertising and consumer culture, without engaging with them outright. Unlike the abstract textual imagery of pop, however, the vocabulary words have a deliberate function relative to the painting’s subject. And that subject itself – a smartly executed portrait of the artist’s wife, documentary in nature of an extended stay in Paris – threatens to mute a purely pop interpretation even further. Like many early Rivers paintings, Parts of the Face points the viewer in many directions, but towards no comfortable end. Thus this section argues that slippery identities, experimentation and a determination to avoid categorisation pervade Rivers’s life and career.

Music and painting

By the time he arrived in Paris in 1961, the world knew Larry Rivers – if it knew him – summarily as a painter. Rivers did not touch a paintbrush until he was in his twenties, however. The first time he did, in 1945,4 he had studied at the Juilliard School in New York and was playing saxophone with a jazz ensemble at a boardwalk casino in Maine.5 He was introduced to painting by pianist Jack Freilicher and his wife Jane, and soon the pastime, enjoyed between nightly gigs, supplanted music as his primary creative concern. In his autobiography, Rivers explored the immediate appeal of painting in the context of his other two passions, writing and music: ‘In painting I could make nameable things, and I could do it alone … Music is abstract, it will always be abstract, and you’ll always need other people to help you make it … Painting was like living, a little lower-keyed than the life I lived, but something I wanted to hang onto.’6

The imagery in the passage is telling: painting as naming, as living at a lower key, painting as a different kind of writing and a different kind of music. Rivers reckoned with disparate art forms in terms of their relationships to each other. Painting (and later sculpture, film and video) offered something different from jazz, but not so entirely separate that he could not relate them intellectually. This polyphony of craft – painting, music making and also writing, which as practice seems to be the driving force behind everything Rivers created – would become an essential facet of the Rivers persona, each mode augmenting the others to shape and complicate his oeuvre. This genre-hopping was also symptomatic of a discomfort with committing himself wholly to any of the dominant creative scenes in post-war America.

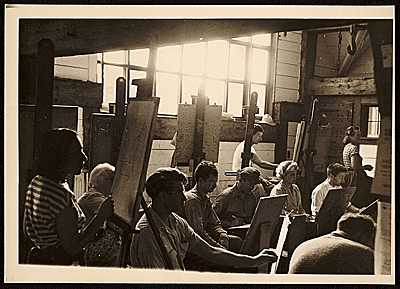

Rivers moved from the Bronx to Manhattan in 1946, and the following year began taking courses in painting from Hans Hofmann, the academic voice of abstract expressionism in New York at the time. While he clearly valued the experience of working with Hofmann, alongside other aspiring young painters (going so far as to follow Hofmann to Provincetown for summer courses), he failed to identify completely with Hofmann’s teaching. Perhaps the theories informing abstract expressionism, linked so often with emergent jazz stylings, were a little too familiar to Rivers the musician, who continued to stalk Downtown clubs by night looking for a place to play his sax. He wanted something else from painting. In a 1961 passage Rivers registered this dissonance, while also drawing a dividing line between himself and ‘every student’ of Hofmann’s: ‘At the end of a year of hearing Hofmann’s talk about push and pull and the importance of this particular phenomenon in painting and seeing every student’s chicken pluckings every day all over the place, I became frantic to draw the figure, and no more advanced than Corot.’7 In a photograph of Hofmann’s Provincetown class at work from around 1945, one student’s canvas displays the ‘chicken pluckings’ against which Rivers would direct his early painting career (fig.1).

Fig.1

A class at the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts in Provincetown, Massachusetts, c.1945

Unidentified photographer

Hans Hofmann Papers c.1904–2011, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

Rivers chased that impulse and his first one-man show, at Jane Street Gallery in New York in 1949, featured mainly figurative works in the spirit of Pierre Bonnard, such as Studio Interior 1948 (fig.2). The show was a success, eliciting the only positive review Rivers would ever receive from the critic Clement Greenberg,8 and Rivers likely felt empowered by the fact that he could paint differently from those of the Hofmann school and still find an audience in New York. He would continue evading the well-trodden turf of modern art as his painting career evolved.

Fig.2

Larry Rivers

Studio Interior 1948

Collection of Gloria and Dan Stern, New York

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Painting and poetry

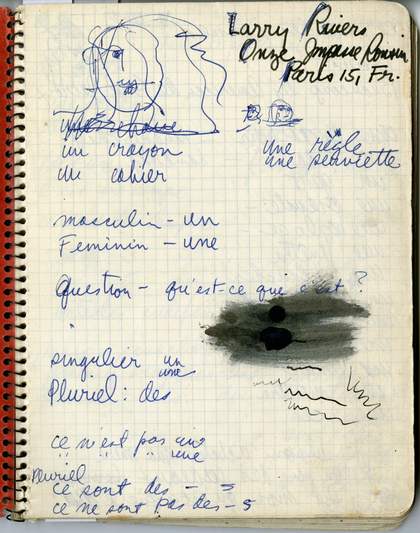

Rivers responded to the prospect of making paintings for a living by skipping town to Paris in 1950 for ‘a half year of deliberating whether I should continue a life devoted to making art or write poetry’.9 Although he never gained notoriety as a poet, Rivers’s devotion to the craft is obvious; the Larry Rivers Papers at New York University’s Fales Library hold sheaves of poems and stories composed throughout the artist’s life,10 and Rivers held an enduring preference for writers as companions and partners in collaboration. It is therefore no surprise to see Rivers, upon his return to Paris in 1961, engaging with language on the canvas in Parts of the Face. A notebook Rivers kept during his 1961 stay reflects this interplay: the first page includes French language notations and a sketch of a woman’s face (fig.3).

Fig.3

Larry Rivers

Notebook page with French language lessons and sketch, 1961

Courtesy the Larry Rivers Foundation

Shortly after returning to New York, Rivers was courted by Tibor de Nagy Gallery and its fawning representative, John Bernard Myers (whose love for the artist culminated in a lawsuit when Rivers left for the Marlborough Gallery years later).11 Painting would be a career after all; Rivers had annual one-man shows at the de Nagy Gallery for more than a decade. It was at this time that Rivers fell in with the poets of the New York School, including John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara and James Schuyler. These friendships and love affairs yielded decades of fruitful collaborations. The New York School poets, in addition to writing copiously about contemporary art, created hybrid works with visual artists, performers and other poets. Rivers became one of their most frequent collaborators, his name and likeness cropping up in their poems while their images graced his canvases. Correspondence in the archives at the Fales between Rivers and the New York School poets reveals a playful exchange of poems, sketches and ideas spanning the 1950s and 1960s. Through his association with the New York School, Rivers found a way to allow writing to inform and strengthen his own work. He also found a support system and promotional apparatus; O’Hara talked Rivers up at the Museum of Modern Art,12 and Ashbery championed Rivers’s poetry and wrote the catalogue essay for his 1962 Galerie Rive Droite show, which included Parts of the Face.

The unarguable idea of being modern

As his profile grew among the greater New York art scene, Rivers gained entrée into a casual intellectual society called the Artists’ Club, a sort of salon for New York art and letters. There he could listen and contribute to weighty theoretical discussions prickled with the friction between established authorities and young upstarts. In a written piece, which survives in his archives, Rivers describes how nights at the Club inspired him while reinforcing the outsider status that came to characterise his style. He admired the Club’s forward momentum, the ‘unarguable … idea of being modern’, despite his own practice: ‘Even though I broke away from all that each time I did certain things in my work, I still felt that what they said stood for something important.’13 Although he stayed confident, blazing his own trail through his work, it remained important for Rivers to find a place in the New York art world’s power elite. Sensing a fragility in his membership, he offered up his musical talents for the Club’s parties ‘so no matter what they thought of the work [he] did as a painter, when they were going to have a little party, they would always ask: “You want to play this weekend?”’.14

Fig.4

Larry Rivers

Washington Crossing the Delaware 1953

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Rivers did have good reason to identify as an outsider from the New York art establishment in the 1950s, and his efforts to establish a unique place are evident in his work from the time. Beyond the fact that Rivers consciously distanced himself from their theory and aesthetic, the abstract expressionists were combative, exclusive and ultimately conformist in their own right, and mocked his work as antiquated and irrelevant.15 He was privileged to find a set of advocates in the New York School poets, who played a crucial role in encouraging the hybrid works he produced in his early career. Indeed, Rivers invoked this negative and positive identification with the New York cultural community in a discussion of his iconoclastic Washington Crossing the Delaware 1953 (fig.4):

My closest friends were three poets out of Harvard a few years who were mad about a great deal of my work. I was energetic and ego-maniacal [sic] and, what is even more important, cocky and angry enough at the time to want to do something no one in the New York art world doubted was disgusting, dead and absurd, rearrange the elements, and throw it at them with great confusion.16

The painting, a combative jab at the hegemony of abstract expressionism (and tellingly, per the artist, inspired more by reading Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869) than by viewing the 1851 painting Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze that formed its basis),17 was therefore enabled in part by Rivers’s confidence not only in himself, but also in the support of writers whom he believed were doing more valuable work than his fellow painters. He would persist in his work from this peculiar standing, deliberately outside of dominant art styles and aligned more closely with a literary scene for which he craved membership.

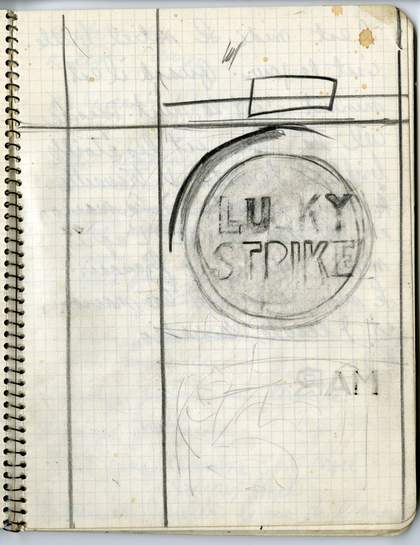

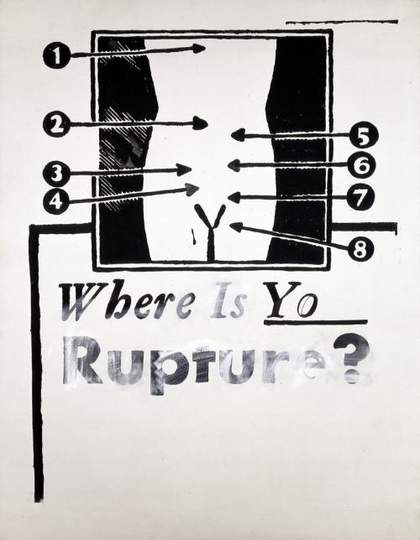

Beginning with Washington Crossing the Delaware and including much of his output of the 1960s (such as Parts of the Face and the Lucky Strike series, an undated sketch for which appears in another of Rivers’s notebooks; fig.5), many Rivers works would be named as progenitors of pop. Warhol pinned Rivers as ‘the daddy of “Pop Art”’ with good reason – in POPism he described Rivers’s work as somewhere ‘in between’ abstract expressionism and pop,18 and identified his participation in the hyper-masculine bar scene of the abstract expressionists as a marker of generational difference.19 Rivers’s 1959 painting Cedar Bar Menu I refracts the iconic artists’ haven through a pop lens (fig.6). The artist himself promoted this association, although again, association was all he could truly claim.20 Warhol’s 1961 painting Where is Your Rupture? [1] (fig.7), a contemporary work with similar source material and performative strategies to Parts of the Face, exemplifies Rivers’s relationship to pop. Both works are based on a pre-existent, low-quality diagram of the body – in the case of Warhol, a newspaper advertisement for a medical product. Both also associate words, images and didactic arrows as the basis for an ironical mode of figuration, questioning painting’s referentiality, as Christopher Penfield discusses elsewhere in this In Focus, and suggesting (possibly sexual) double meanings.21 It is clear, however, that these works do not share common aims.

Fig.5

Larry Rivers

Notebook page featuring preliminary sketch for Rivers’s Lucky Strike series, 1960s

Courtesy the Larry Rivers Foundation

Fig.6

Larry Rivers

Cedar Bar Menu I 1959

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Fig.7

Andy Warhol

Where is Your Rupture? [1] 1961

Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica

Parts of the Face orchestrates a contrast between the materiality of paint and colours and the flatness of the diagram, between the specific features of Rivers’s model and the generic descriptive words. His engagement with the world and with the physical act of painting is deliberate. Where is Your Rupture? appears as a work of transition, aiming at the progressive disappearance of remaining traces of artistic expressivity and the eviction of any reference to the world not already mediated by a pre-existing image.22

Rivers arrived in Paris in 1961, then, with a singular artistic identity. His works featured visual nods to both abstract expressionism and pop, but at the same time seemed to subvert their underlying philosophies. He countered the contemporary art world’s aversion to the figure, but never in the service of purely realistic or historical painting. Crucially, as the literary critic Marjorie Perloff put it, Rivers ‘could not abide an aesthetic that separated the visual arts from his other two loves, jazz and poetry’.23 Rivers aspired to make of his paintings songs, or poems, and that superfluity of influence produced works like Parts of the Face, remarkable for their evasive nature, their tendency to slip into so many easily pegged categories and ultimately point towards something different, and all their own.