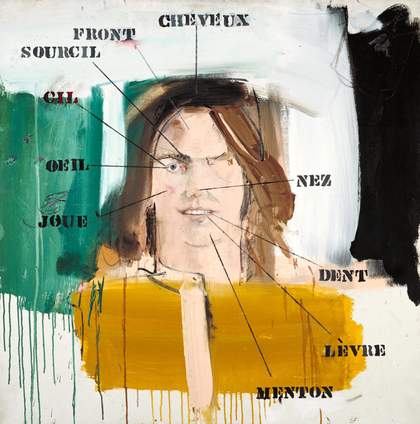

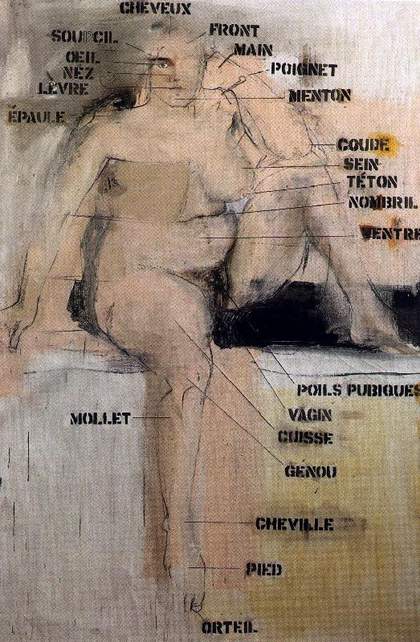

Fig.1

Larry Rivers

Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson 1961

Tate T00522

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Photo © Tate

Larry Rivers’s solo show at Galerie Rive Droite in Paris, where Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson 1961 (Tate T00522; fig.1) received much attention, opened on 10 April 1962. This was just two days after the national referendum approving the Evian Accords, which put an end to eight years of decolonisation war in Algeria and Paris. Nothing in Rivers’s exhibition explicitly referred to the war itself, nor to the attacks of the OAS (Organisation de l’Armée Secrète), a dissident terrorist group fighting against Algerian independence whose bombings had been spreading terror in Paris for the past fifteen months, nor to the abuses of the French military in Algeria, which had started to break news. In his review of Rivers’s exhibition, the art critic Michel Ragon rather undermined the significance of the themes chosen by ‘one of the leaders of American neo-dada’: ‘Figures detailed like anatomical charts. An imagery borrowed from banknotes and cigarette packs; a familiar mythology, from Buick to de Gaulle, Kennedy and Bonaparte … All this with a naïve taste for provocation, but evident qualities as a painter’.1 Can we so easily conclude, however, that nothing of the extreme violence of the climate in Paris in late 1961 and early 1962 penetrated Rivers’s paintings?

Fig.2

Enrico Baj, Roberto Crippa, Gianni Dova, Erró, Jean-Jacques Lebel and Antonio Recalcati

Le Grand Tableau Antifasciste Collectif 1960

Despite the rallying of an increasing number of writers and intellectuals against the war in Algeria, artworks that outspokenly addressed this question remained few, and were subject to censorship and self-censorship.2 The large-scale, collective painting entitled Le Grand Tableau Antifasciste Collectif 1960, exhibited in Milan in 1961 during an artistic event denouncing the war in Algeria and the use of torture, is exemplary (fig.2). The distorted figures, their mouths open in cries of terror and pain, express the violence unleashed by the French Republic; a swastika directly links this state barbarity to the practices of the Gestapo during the occupation. At the lower-right corner, a collaged copy of the 1960 Manifeste des 121, a pamphlet signed by 121 famous intellectuals and artists claiming a right of insubordination against the Algerian war, makes the connection between the painting and current events even clearer. Unsurprisingly, the painting was seized by the Italian authorities and sequestrated until 1987.3

Such explicit references to the war were absent from most artworks produced in Paris at the beginning of the 1960s. In his defence of nouveau réalisme, critic Pierre Restany specifically insisted on its political neutrality, in favour of the ‘sociologic reality’ found in the nouveaux réalistes’ appropriation of consumer objects and new media.4 However, subsequent scholarship on 1950s and 1960s French art has led to a better understanding not only of the political undertones of some of the nouveaux réalistes’ works of this period, but also of the reasons why they remained neglected or unseen for so long. The art historian Jill Carrick has suggested that Restany’s reading of nouveau réalisme, which remained largely dominant almost until his death in 2003, attempted to ‘dislodge the avant-garde from its longstanding if unstable associations in France with leftist political engagement’.5 Furthermore, as art historians such as Laurence Bertrand Dorléac and Hannah Feldman have argued, in the context of an identity crisis and a war that did not tell its name – the French authorities spoke not of ‘war’ but only of ‘pacification’ or ‘public order operations’ – much of the most pregnant political issues required a new regime of representation, one that did not necessarily coincide with former traditions of art engagé.6

This essay will contribute to this revision by arguing that despite its apparent disconnection from current events, Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson can be interpreted in the context of the war in Algeria. Although Rivers’s painting can in no way claim to offer the kind of unambiguous engagement with the subject seen in Le Grand Tableau Antifasciste Collectif, this study will explore some biographical and visual clues that suggest that Rivers’s Paris exhibition may have had a surreptitious agenda beyond its overt neutrality. An in-depth analysis of the reception of Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson in relation to contemporary images and debates will be used to propose a hypothesis as to how a different kind of political art could be activated.

The visibility and invisibility of political art

Rivers’s stay in Paris, from autumn 1961 to spring 1962, coincided with the final phase of the violent conflict that ended with the independence of Algeria. After the defeat in Indochina (1954), the independence of Tunisia and Morocco (1956) and the decolonisation of sub-Saharan French Africa (1956–60), Algeria was virtually the last remains of the former French colonial Empire, once immense and second only to the British Empire. Between 1954 and 1962, the war waged violently both in Algeria – between the FLN (Front de Libération National, the Algerian political movement fighting the French authorities) and the French military forces – and in metropolitan France, in particular when the OAS started its bombings and assassinations in 1961.

In his correspondence from Paris, Rivers mentioned the war only very casually. In early March 1962, at the height of an almost uninterrupted cycle of violent attacks in Paris and Algiers – among them an attempt to bomb French culture minister André Malraux’s apartment in Boulogne-sur-Seine – Rivers wrote:

As for bombs plastiques O.A.S. & such, it goes on but it is such a big city & busy one is so caught up in their own small ‘gorgeous’ lives it is only newspaper headlines like Muggings Rapes etc. at all rate it’ll be over soon & like all selfish sweet human being I hope it quiets down at least a few days before my show.7

Rivers may have had in mind the fate of Robert Rauschenberg’s opening at Galerie Cordier in April 1961: it coincided with the ‘Algiers putsch’, an attempted coup against President Charles de Gaulle, during which the gallery had to close its shutters.8 Such a detached attitude comes as a surprise from an artist who had a reputation for feeding on political scandals. Rivers’s depictions of American flags, of Washington Crossing the Delaware 1953 (Museum of Modern Art, New York) and of Civil War veterans had created a shock in the cold war climate of 1950s America.9 In an article from December 1961 the art critic Irving Sandler described this evolution, writing that Rivers was ‘an artistic and political seismograph – a new kind of social realist’. However, ‘This attitude has changed somewhat in recent works. He remains a reporter – cool, urbane and committed to touching the pulse of life around him’.10 This refusal to express public commitment seems to have reached a peak during his stay in Europe. Guardian journalist George Butcher, commenting on the discussion between Rivers and the British ‘pop’ painters at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in May 1962, reported: ‘Busting up the whole mood, the young “pop” artists kept pursuing the thread of “responsibility”, and trying to pin Rivers down to some form of social commitment. They failed’. Butcher added, however, that ‘in spite of himself, and rather like the surrealist core behind Dali’s posturing, there is much that is eminently serious behind Rivers’.11 This seriousness and political engagement came to light again soon after his return to New York. In the mid-1960s he was described again as ‘an inveterate panelist and petition-signer’ who had ‘a fascination with politics’; for his 1966 Jewish Museum show he presented himself as ‘a political man’.12

Fig.3

Photograph of the first shooting for Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tirs paintings, with Pierre Restany shooting and Jeannine de Goldschmidt, Daniel Spoerri and the owner of the gun standing by, 11 Impasse Ronsin, Paris, 12 February 1961

Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Photo: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust

Fig.4

A visitor shooting at Niki de Saint Phalle’s exhibition Feu à Volonté, Galerie J, Paris, 1961

Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Photo: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust

Rivers’s apparent detachment throughout his stay in Europe should be questioned further considering his closeness to his friends and neighbours in Paris, Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely.13 In February 1961 Saint Phalle inaugurated a form of artistic performance that would bring her to fame almost instantly: her Tirs, or shooting paintings. Armed with a rifle, she shot canvases adorned with polythene bags full of paint or ink and covered in plaster, thus making the painting ‘bleed’ and producing drippings of colour. Several photographic and filmed sequences show her, her friends and the public shooting in diverse places, such as Impasse Ronsin (fig.3), where she lived with Tinguely next door to Rivers, or in the Parisian Galerie J (fig.4). While the Tirs have been largely read as a form of violence related to gender issues – both at the time and in later art historical accounts – the importance of the context of war is now well-recognised.14 The choice of the title Autel O.A.S. for a 1962 work by Saint Phalle (Colllection Jackie Matisse) reinforces this interpretation: it is a golden altar adorned with religious imagery, a stuffed bat and pistols, that Jean Larcade daringly exhibited in the window of the Galerie Rive Droite for Saint Phalle’s exhibition in June 1962.15

From today’s perspective, it is quite distressing to look at the Tirs pictures: men and women armed with rifles, laughingly and publicly shooting sometimes human-like figures on a canvas, at a time when Paris was under a semi-permanent terrorist alert and when young French conscripts were being trained and sent to Algeria to allegedly ‘maintain peace’. This ambiguous, parodic and almost playful atmosphere also characterises Tinguely’s self-destructive machines of the same period, such as his Homage to New York 1960 (a ‘fragment’ of which is held in the Museum of Modern Art, New York). The tone is quite far from the expressive and denunciative Grand Tableau Antifasciste Collectif, although Tinguely himself was involved in the 1961 anti-war event in Milan where the painting was exhibited.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, in her book L’Ordre sauvage, has argued that the reference to the Algerian war in these ambiguous works was neither a definite commitment in the traditional sense, nor a mere ‘alibi’. What these actions demonstrated was ‘a type of obstinate resistance to traditional models of expression, information and political engagement’.16 In From a Nation Torn: Decolonizing Art and Representation in France, 1945–1962, Hannah Feldman expands this argument in a discussion of the visual dimension of the decolonisation wars on the Parisian cultural scene. Although she does not mention Rivers, Feldman offers precious insights that help to understand the apparent silence of the artist on this subject, and how we might read into this silence. Aesthetic practices, she argues, ‘were a primary ground upon which the conditions of coloniality and postcoloniality were imagined and contested’.17 What was at stake was not merely the chance to openly take sides or commit to a cause, but rather to renegotiate the visual modalities of identity, domination or belonging: what were ‘past’ and ‘present’, ‘them’ and ‘us’, what should be discussed or silenced, shown or withdrawn from view. According to Feldman, in the midst of the ‘legal amnesia’ that struck France in the so-called ‘post-war’ period – a refusal to take responsibility for collaborating with the Nazis, as well as for the ongoing wars in the colonies – a battle was fought to rewrite history and geography, to deny or achieve visibility. As the following paragraphs will argue, this is what was at stake in Larry Rivers’s 1962 Paris and London exhibitions. By sketching the conditions of visibility of the period, we might recover the political dimension of Rivers’s work, which was then quickly lost in its retrospective reception.

An inventory of one’s possessions

According to the French art critic Alain Jouffroy, in his 1962 Paris exhibition Rivers acted as a ‘reinventor of history painting’.18 Indeed, French history and geography, as they were being officially reconstructed under the pressure of decolonisation, constituted one important thread of Rivers’s new paintings.

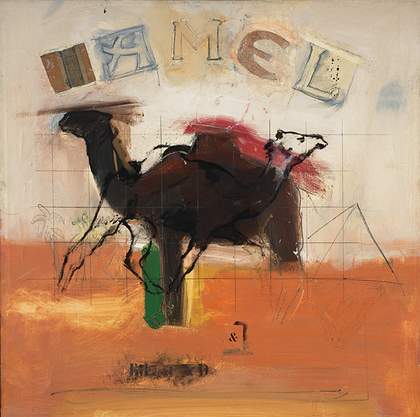

Fig.5

Larry Rivers

Amel-Camel 1962

Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Fig.6

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

A dos de chameau 1881

Private collection

This was most evident in Rivers’s series of Camel paintings from the early 1960s (see, for instance, Amel-Camel 1962; fig.5), which borrowed from the famous packaging of the eponymous cigarette brand. While the paintings could be read as the appropriation of banal and vulgar material extracted from consumer society, they also brought to mind the exotic, ‘orientalist’ imagery which, in the nineteenth century, accompanied the French conquest of North Africa. For instance, Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s A dos de chameau 1881 (fig.6), painted in Algeria, was shown in 1930 in Paris in an exhibition devoted to the centenary of the French conquest of Algeria; it was displayed again in 1958 in New York, where Rivers, who admired Renoir, might have seen it.19

Rivers’s Camels elicited the only commentary of the time that directly linked his Parisian paintings to the context of the Algerian war. It was provided by the famous critic Harold Rosenberg:

Rivers’ camel keeps trying to move off the cigarette package so it can take him for a ride to Africa. While he was painting it, the Algerian war was in the news and Rivers has a sense (vague) of world citizenship. The imaginative pressure to which he subjected this exotic but too familiar beast gives it a disreputable air in comparison with its well-groomed and shiny model … In its intense look there is much of a Rivers self-portrait.20

Colonial imagery was also present in Rivers’s French Money paintings (fig.7), exhibited next to the Camels and Vocabulary Lessons in Paris and London. Paintings in this series are based on the front and back of a 100 New Francs banknote, called the ‘Bonaparte’ banknote (which was itself parodied in a fundraising leaflet put out by the OAS in January 1960; fig.8). As a French imperial hero, founder of the Bank of France and also victor in the invasion of Egypt in 1798–9, Napoleon Bonaparte was a much-solicited historical figure at a time when France’s pride and international power were contested, particularly in North Africa. In contrast, Rivers’s Napoleons have lost much of their heroism and ardour as they blur into swathes of springtime colours.21 Like Niki de Saint Phalle or Jean Tinguely, Rivers does not attempt to take a clear side. He chooses a ludic, light atmosphere to convoke and replay a set of visual conditions that were precisely a locus of conflict at the time of decolonisation.

Fig.7

Larry Rivers

French Money II 1962

Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Fig.8

Fundraising leaflet by the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète, 1960

Collection of Herbert A. Friedman

Exhibited together with the Camels and the French Money paintings in Paris and London in 1962, the Vocabulary Lessons also arguably deal with colonial themes. They play with the conventions of French history and geography as they were becoming increasingly sensitive issues during decolonisation wars.

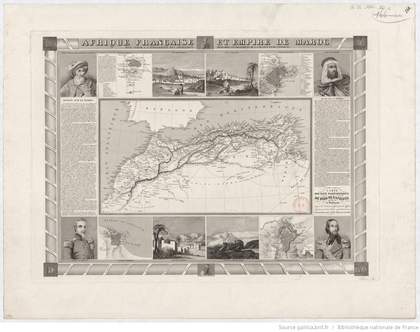

Fig.9

Alexandre Vuillemin

Carte des pays barbaresques du nord de l’Afrique: Afrique française et empire de Maroc pour servir à l’intelligence des opérations militaires et politiques de la France et de l’Espagne 1844

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

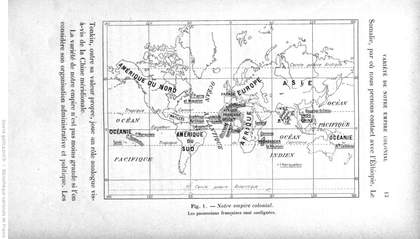

Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson can remind us of another form of ‘labelled’ images: maps. The straight lines connecting visual forms to their names, encircling the shape of the face, is reminiscent not only of anatomical charts, but also of cartographic conventions, where the names of coastal cities double the outline of the seashore. Such visual conventions were common in colonial maps of North Africa, such as that composed by Alexandre Vuillemin in 1844 (fig.9). Labelled drawings were therefore part and parcel of this colonial imagery, together with exotic views of ‘oriental’ landscapes and animals, or portraits of military heroes. While cartography, arguably, is always about asserting one’s power, colonial maps are particularly transparent in their attempts to claim a nation’s rights to land, in a performative way.22 Labels, in this case, are an inventory of one’s possessions. In a map of 1910 entitled Notre empire colonial (‘Our colonial empire’; fig.10), quite characteristic of the simplified cartographic representations available to pupils in French schoolbooks up until the decolonisation, the caption candidly announces that ‘French possessions are underlined’. Drawn lines are thus literally visual markers of power and possession. Language – in particular the French, so proudly imposed in the colonies – becomes an instrument of domination; vocabulary lessons transform into obedience lessons.

Fig.10

Henri Busson, Joseph Fèvre and Henri Hauser

Map from Notre Empire colonial, Paris 1910, p.13

Women’s bodies at war

In the Vocabulary Lesson paintings (see fig.1 and Parts of the Body – French 1962; fig.11), it is not the land but the face and body of a woman – the artist’s model and wife – which is subjected to this objectification and dispossession. It is striking that although they did not mention the war, nearly all of the contemporary commentators on the Vocabulary Lessons paintings in Europe perceived the works’ implicit violence. Rivers’s figuration, Michel Ragon wrote, ‘handles humour, but a sinister humour. Its world is one of disaster. It is the expression of our anxiety, our complex and our fear’.23 Even more specifically, he added in another article,

Larry Rivers transforms his own wife into an anatomical chart. So doing, he makes her derisory with a touch of obscenity. Deprived of women’s body for so long by abstract art, avant-garde artists today rediscover the woman with a kind of perverse pleasure … Renoir, too, was obsessed with the female body, but he magnified it. His joy in front of the woman was full of robust health. Why does our generation have to give us of the woman only such pitiful images?24

Fig.11

Larry Rivers

Parts of the Body – French 1962

Private collection

© The estate of Larry Rivers

Death, perversity and corporal decay were also at the centre of the work’s reception in London. George Butcher wrote in the Guardian, also mentioning Renoir:

one wonders how the critic for Figaro, who once wrote in 1875 of the ‘five or six lunatics’ exhibiting at Durand-Ruel, would have risen to the occasion of Larry Rivers’s recent London exhibition at Gimpel Fils. If he was able to lecture Renoir on how ‘a woman’s torso is not a mass of flesh in the process of decomposition with green and violent spots which denote the state of putrefaction of a corpse’, what might he not have been able to say of Rivers’s ‘Parts of the Body’, an untidy picture of his wife in the nude, with the major anatomical parts, including the most unmentionable, all neatly labeled in French.25

To understand why Rivers’s seemingly playful and innocent portraits thus triggered visions of corpses and outrage for contemporary viewers, we have to turn to the role of the woman’s body in public discourse in 1961–2, at the height of the Algerian war.

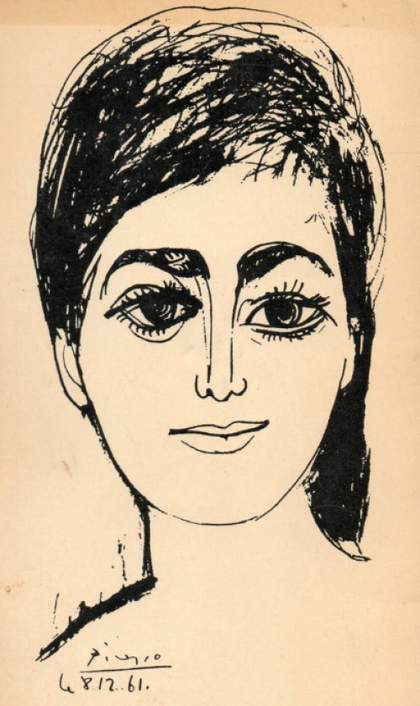

In 1961–2, at the time of Rivers’s stay in Paris, the denunciation of the Algerian war was taking a new form as the scandal regarding the torture methods used with impunity by the French military in Algeria finally broke out in the press. Although such atrocities had been denounced publicly at numerous occasions since the late 1950s, a relative silence on the subject had been maintained by systematic state censorship.26 In 1960, however, the case of an Algerian woman federated the voices that were raised against torture, and succeeded in arousing public indignation. Djamila Boupacha, an activist of the FLN, was violently tortured and raped by the French military after her arrest in February 1960. Her lawyer, Gisèle Halimi, decided to make her cause a symbol of the quotidian abuses committed in Algeria. She solicited Simone de Beauvoir, who wrote for the press and created a support committee joined by esteemed writers, intellectuals and former résistants, such as Louis Aragon, Aimé Césaire, Jean-Paul Sartre and Germaine Tillion. Boupacha’s trial in 1961 was followed by all major national and international media. In the winter of 1961–2, when Rivers was working on Parts of the Face, Halimi and de Beauvoir published her testimony in a book entitled Djamila Boupacha, which included contributions by supportive painters, among them Pablo Picasso. The latter’s portrait of Boupacha (fig.12) instantly became iconic, especially as it was used as an advertisement for the book. If torture had deprived the young woman of her own body, this simple and respectful portrait, bearing no trace of the abuses she experienced, seemed to give her back her own distinctive, dignified facial features.

Fig.12

Pablo Picasso

Portrait of Djamila Boupacha, 8–9 December 1961

Private collection

Reproduced as the frontispiece to Simone de Beauvoir, Djamila Boupacha, Paris 1962, and in Les Lettres françaises, 18–24 January 1962, p.1

Boupacha’s testimony, as it was widely quoted in the press from 1960 to 1962 and then given in full in the book, was especially striking as it daringly named what torture really was, in words that broke brutally with what were then the conventions of female decency and reservation. Boupacha explained how electric wires were stuck to her skin with rubber tapes, listing one by one the parts of her body concerned: first the breasts, then ‘the legs, the groin, the genitals, the face’.27 Being able to utter these simple words was, according to Boupacha’s lawyer, a victory at a time when an oppressive silence weighed on France and its colonial wars: ‘Djamila was liberated: she had finally spoken’, she wrote.28 In Le Grand Tableau Antifasciste Collectif Boupacha’s body is crudely represented, quartered, her legs open in the paroxysmal violence of rape. It was under the pretence of pornography that the painting was censored by the Italian authorities, as though the incapacity for naming and showing the body went together with the incapacity for facing the war.29

It is not the intention to claim here that Rivers had Boupacha in mind when he made his Vocabulary Lesson paintings – although he might have – nor that his portraits of his wife were influenced by Picasso’s, or that his obsession for naming the parts of the female face and body was connected in any direct way with Boupacha’s story. What I contend, however, is that it was in this precise visual climate that his paintings were initially seen. When confronted with Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson, a viewer in spring 1962 would have had in mind, consciously or unconsciously, Picasso’s omnipresent portrait of Boupacha, with her beautiful asymmetric eyes. Likewise, the cold, inexpressive and almost scientific indecency of Parts of the Body would have resonated with the routine crimes of war that were then being inflicted on the body, particularly the female body.

Today, Parts of the Face: French Vocabulary Lesson may not strike us as a product of war, even less as a condemnation of war. The humorous and playful aspect of the painting seems more enduring. Recovering the political conditions for viewing the painting in 1962 is nonetheless important in demonstrating its plasticity, its richness of meaning. Whether Rivers’s art should be considered a critique or a reinforcement of such colonial violence remains deliberately ambiguous. Rivers never sought the kind of definite engagement seen in Le Grand Tableau Antifasciste Collectif; it was enough for him to amuse and perhaps irritate the viewer, and to trigger his or her imagination.