Fig.1

Theodore Roszak

The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952

Steel

371 x 476 x 229 mm

Tate N06163

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Fig.2

Theodore Roszak

Eagle Sculpture 1960

Aluminium

Width: 11000 mm

Former American Embassy, Grosvenor Square, London

© Theodore Roszak/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2018

Photo © Bob Speel

Although scholarship on art’s role in the Cold War has been dominated by accounts of abstract painting, Roszak was among a number American sculptors whose work was also implicated in international diplomatic activities in the 1950s.1 This largely unrecognised aspect of Roszak’s career was arguably instigated by his involvement in the International Sculpture Competition, to which he submitted The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) (fig.1). In the decade that followed, Roszak became increasingly involved in a wide range of state-sponsored cultural activities of a propagandist bent, culminating with the installation of his gilded aluminium sculpture of an eagle on the roof of what was then the American Embassy in London’s Grosvenor Square in 1960 (fig.2).2 This section will locate The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) within the artist’s involvement in the ‘cultural cold war’ over the intervening years.3

If a sculpture competition might appear of little significance in the context of Cold War international relations, an anecdote concerning an entrant from Indonesia reveals the serious attention the initiative attracted from Soviet officials. In his 1958 autobiography covering his time teaching in Indonesia, the British academic Robert Forster recalls having ‘the invidious task of presenting and explaining the disappointingly meager cheque’ issued to figurative sculptor Edhi Sunarso for his entry to the competition depicting a man in chains.4 It was, he writes, ‘a task made doubly embarrassing by the counterstroke of the Iron Curtain, [who offered the artist] a six-months’ scholarship abroad. The Communists were assiduous in their wooing of Asia’s intellectuals’, who were forever ‘hastening off to such improbable art centres as Poland or Bulgaria’.5 According to Forster, Sunarso left for Bucharest the day after accepting his pitiful prize money from the West.

The contested merits of abstraction were at the heart of such jockeying, and the ideological alignment between its manifestation of free artistic expression and freedom itself was crucial to frameworks of the International Sculpture Competition. Art critic Emily Genauer writing about the exhibition of American finalists at MoMA asked:

Could the jury have bent over backward in nominating chiefly a group of abstractionists for these awards for a public monument to an unknown political prisoner because subconsciously and understandably it was mindful of how the dictatorships have made political prisoners of the artists working in the abstract idiom? Did it thereby manifest its own possible and unwitting imprisonment by certain pressure groups for perhaps transient esthetic styles.6

In the context of such criticisms, Roszak’s comparatively moderate position between abstraction and figuration acquired particular utility for the increasingly ambitious exhibitions of the cultural Cold War later in the 1950s.

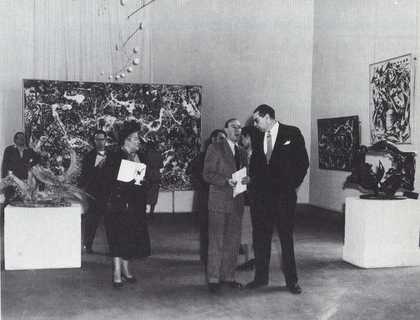

Fig.3

Press opening of the exhibition Twelve Modern American Painters and Sculptors, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, 1953

Despite the emphasis on New York School painting in accounts of the internationalisation of American art and its political ambitions, it was more typical for state-sponsored exhibitions of art from the US to emphasise a diversity of schools and stylistic approaches, even if such exhibitions still tended to suggest a developmental narrative from realism towards ever increasing abstraction. For Twelve Modern American Painters and Sculptors, which opened at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris in April 1953, Roszak’s works were surrounded by paintings by Jackson Pollock (fig.3). But in other rooms of the exhibition, visitors saw realist painters such as Ben Shahn and Edward Hopper in dialogue with abstract sculptures by Alexander Calder and David Smith – juxtapositions that undoubtedly brought out the abstract aspects of the figurative works, and vice versa.7 Such heterogeneity served ideological ends. As curator Andrew Carnduff Ritchie made clear, the exhibition sought to emphasise the ‘diversity of American modern art’, as well as, the ‘absence of any “official” art that could be said to dominate artistic practice’.8

Twelve Modern American Painters and Sculptors saw Roszak’s works exhibited in Oslo, Helsinki, Stockholm, Dusseldorf and Zurich through 1953–4. Spectre of Kitty Hawk was also included in Modern Art in the United States, organised by the Museum of Modern Art, which travelled to the Tate Gallery in London, as well as Zurich, Barcelona, Frankfurt, The Hague, Vienna, Linz and Belgrade. The latter destination was the first major exhibition of modern American art to be presented in a communist country, and was organised by the US Embassy in Yugoslavia. The profile that Roszak acquired with these exhibitions was amplified in publications of an equally propagandist bent, including America Illustrated and Perspectives USA.9 In the latter magazine, Roszak’s sculpture appeared alongside an account of the very phenomenon in which it was participating – an essay by diplomat George Kennan describing ‘the importance of international cultural exchange from the standpoint of our relations with other countries’.10

Fig.4

Theodore Roszak

Cradle Song 1955

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

Fig.5

Theodore Roszak

Migrant 1950

University of Illinois Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

In 1958 Roszak was one of the sculptors selected to represent the United States in the art exhibition at the Brussels World’s Fair. Again, the emphasis here was on pluralism: the co-existence of divergent styles united only by their expression of artistic individuality. Roszak’s formal references to the natural world and evocative titles made his work especially useful in this regard. ‘Much abstract or semi-abstract art retains imagery to some extent, and has some relation to visual reality’, noted Lloyd Goodrich in his essay for the exhibition catalogue.11 The display included Roszak’s Cradle Song 1955 (fig.4) and Migrant 1950 (fig.5), while the latter was also selected by the USIS Library at London’s American Embassy for the show Seventeen American Artists + Eight Sculptors, which was drawn from the Brussels exhibition. The London presentation was predictably ideological, aligning artistic diversity with freedom of expression and individualism. Its catalogue declared: ‘As the world becomes smaller and the community of mankind moves inexorably closer together, the free artists of America speak their own particular dialect of the international language of art.’12

Such alignments between internationalism and modernism implicitly omitted Soviet art from their frameworks, a marginalisation that had been even more explicit in the International Sculpture Competition. The entry form had indicated that Vladimir Kemenov would be the judge representing Russia, but pointedly noted that his acceptance had not been received at the date of going to press.13 A subsequent press release confirmed that Kemenov was ‘unable to serve as member of jury panel’.14 When Roszak was himself consulted on a later, supposedly international project, he gave a sense that he understood these dynamics: ‘The weakest and least effective representation, however well supported, would probably come from the USSR, since they are considerably outside the pale of western contemporary norms and free creative enterprise’, even if ‘protocol necessitates the consideration if not overt inclusion of the USSR’.15

Fig.6

Theodore Roszak

Hound of Heaven 1953–4

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The estate of Theodore Roszak

Roszak’s views on Soviet art were informed by his fraught involvement in the jury that selected the artists for the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959. Along with painter Franklin Watkins, Whitney Museum director Lloyd Goodrich, and art historian Henry Hope, the panel had been ‘assured absolute freedom of selection without pressure from any group, institution or governmental agency’.16 The inclusion of émigré painters and sculptors served – as the Washington Post noted – to showcase ‘America’s role in welcoming foreign artists’, and Roszak’s role as a judge no doubt served a similar function.17 Roszak’s own sculpture Hound of Heaven 1953–4 (fig.6) was loaned from the Museum of Modern Art, while his evidently Eastern European surname helped demonstrate the possibility for artists to reject the restrictions of national heritage.18

In the United States, Roszak’s surname required other defenses. A 1937 biographical statement is typical in its insistence that Roszak was ‘brought to this country at such an early age ... that he may be set down as an unhyphenated American’.19 When hearings from the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) attacked the selection of artists for the Moscow exhibit, Roszak’s own allegiances were called into question. As evidence of the idea that ‘art is used by the Communists as a weapon’, conservative figurative sculptor Wheeler Williams named Roszak as a ‘recently made American’ who ‘happens to be a Polish-American who has been in this country a relatively short time’, despite the fact he had lived in the United States for fifty years.20 ‘He came over, I believe, went back, and came back again’, Wheeler claimed.21

Wheeler’s testimony argued that ‘social protest’ artists like Ben Shahn and Philip Evergood, and more abstract artists including Mark Rothko, Isamu Noguchi and Jackson Pollock (whose work he characterised as ‘meaningless doodles’), were all part of the vast Communist conspiracy he thought had infiltrated the American art world – the latter were merely ‘less gifted’ than their realist comrades.22 The committee responsible for curating the Moscow exhibit relayed in a telegram to President Eisenhower that withdrawal of the collection ‘would give the Soviet propagandists an ideal weapon to attack our democratic freedom’.23 In a statement prepared for Radio Free Europe a year earlier, Roszak’s own estimation of Soviet art claimed it as an example of:

how thought control can distort and caricature ideas and intentions. The first impression on gains from the general effect of Russian Art is one of trite sentimentality, lacking in strength and completely lacking in spirit ... It is apparent that the painting and sculpture of the soviet artist bears the apathy of a weary and overworked stenographer who is subjected to the monotonous task of an endless and dreary dictation.24

Roszak’s statement was undoubtedly useful for the Cold War imperatives of the CIA, who funded Radio Free Europe, but it is worth noting that his criticism of a state-controlled art falls short of condemning the state itself. ‘Where in Russian art is the visual equivalent of the powerful masses, or where is the stamp of the rugged and invincible strength ... heralding the regenerated life of soviet man’, Roszak asked, his terms recalling the character of his own thrusting figure of defiance and triumph from a decade earlier. If Roszak found Soviet art, and by extension its society, to lack spirit and strength, his recognition that an art might aspire to provide a ‘visual equivalent of the powerful masses’ bares some trace of prior commitments. In 1936 Roszak was involved in the American Artists Congress, and even though he was undoubtedly at the liberal end of its membership, he was not alone in setting aside such leftist commitments within the fraught context of McCarthy-era politics.

By 1960, the installation of Roszak’s eagle at the American Embassy in London (fig.2) would mark the culmination of the artist’s close involvement with the symbolic representation of the United States abroad. This work is connected to The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) not simply because of its monumental scale, or even because of its London location, but because of the role that the American philanthropist John Hay Whitney played in its realisation. As explained in the first section of this project, Whitney was the anonymous funder of the International Sculpture Competition. In February 1957 he moved to London to take up the post of US Ambassador to the United Kingdom, by which point plans for the new Grosvenor Square embassy were already well advanced.25 Models of Eero Saarinen’s architectural design published the same month that Whitney arrived in London appear to have still featured a ‘Great Seal of the United States’ to be ‘carved in Portland Stone’ rather than the aluminum eagle that was eventually installed.26 The idea to replace the Great Seal on the front of the building with an eagle therefore seems to have occurred after Whitney’s appointment. Saarinen had worked with Roszak before, but it also seems likely that Whitney would have taken an interest in the sculptural decoration for the building.

Whitney had joined the MoMA board in 1930, becoming its vice president in 1937 before taking over from Nelson Rockefeller as president in 1941.27 He played an especially active role in maximising the propagandist possibilities of the museum’s collection in the international sphere, and had also worked with Rockefeller in the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, where he was central in persuading filmmakers to further American interests in Latin America. When MoMA announced the forthcoming exhibition Twelve Modern American Painters and Sculptors in 1953, Whitney explained to the press that it was using the arts ‘to foster understanding and friendship between nations’.28 As Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Whitney was equally attentive to the political utility of art, even hanging a painting in his collection by President Eisenhower – for whose Presidency he had helped fundraise – alongside works by Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso.29

In July 1957, shortly after Whitney began in office, Saarinen wrote to Roszak informing him that ‘Nobody has taken an violent exception to the principal that there should be a large scale eagle on the front façade’, hinting at the possibility for this charged national symbol to have provoked controversy.30 In line with such anxieties, Saarinen even recalled that the character of Roszak’s bird had been altered from ‘fierce’ to ‘benevolent’ as its design was finalised.31 Roszak sent his first detailed drawings in October 1957, and after lengthy discussions concerning the design and fabrication, his sculpture was finally approved in March 1959. Roszak produced eight scale models before a final work in timber and cardboard was produced at full size.32 ‘Let’s hope they don’t call this a vulture’, was reportedly Whitney’s response to Roszak’s final design.33

Roszak’s commission sent him back to the florid, windswept forms of his other sculpture in London, the no less propagandist The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant), and it is known that the earlier International Sculpture Competition was on Whitney’s mind around this time. In early 1958 the art historian and former director of MoMA Alfred Barr had been in touch to try to resuscitate the project. Barr explained to Whitney that ‘the backers’ had ‘reneged’ from their ‘obligation’ to pay for the monument, and hoped that Whitney ‘might be able to discuss the matter in Washington’.34 Barr knew well that it was Whitney himself who had provided the funds, but the letter was careful to reassure the ambassador that the anonymity of the backer had been ‘scrupulously observed’.35 A subsequent letter from Barr to Roland Penrose elaborates further on the ‘delicate matter’ of such disclosures:

Shortly after Christmas I was able to see J.W. for a half hour’s talk about the monument. I spoke very candidly with him and although much was left unsaid I think it was mutually understood. Because of the character of his involvement I think he has no bad conscience about the matter, and in this I believe he is justified. Nevertheless, he does feel involved and I hope may be able to act.36

The failure of Reg Butler’s first-prize-winning monument to garner the support of Whitney or his contacts in Washington seems to have been connected to the controversy produced by its abstract form. As art historian Robert Burstow has speculated, ‘Perhaps the backers anticipated that the Grand Prize would be won by a moderate “humanistic” modernist, like Henry Moore’.37 Whitney’s own tastes were evidently cautious; when his art collection was exhibited at the Tate Gallery in 1960 the show was dominated by French impressionism and post-impressionism, even if the catalogue noted that his role at MoMA had brought him ‘into intimate touch with their most recent developments’.38 ‘Where American painting is concerned the taste shown is markedly conservative’, reported the critic John Russell in the Sunday Times.39 So while Reg Butler’s proposal would never be realised at full scale, Roszak’s sculpture for the US Embassy might well have been understood as something of a substitute, allowing another of the competition entrants to realise a monumental work on a ‘site of international importance’ in one of ‘the great capitals of the world’, just as the competition had originally promised.40

Art News might have named Roszak’s earlier proposal as the likely ‘popular favorite’ before it was sent to London, but by the end of the decade the artist’s less ambiguous contribution to the embassy design took flight within very different context.41 Even before Roszak’s sculpture was installed, Labour MP Marcus Lipton told the House of Commons that the design was a ‘blatant monstrosity’ and called up the responsible minister to ‘give it the bird’.42 ‘Trust the Americans to rub it in!’ complained the leftist Daily Worker. ‘Their H-bombers fly over us, their rocket bases put us in the front line, their Polaris submarines will soon be based here ... but not content with the reality of their domination over our subservient rulers, the American big shots insist on symbolising it all with a monstrous 35 foot eagle’.43 Asked about his views on the controversy, Roszak told the Washington Post that he thought it was all ‘a lot of huff’.44

Roszak, for his part, sought to expand the symbolic register of his embassy sculpture from a national to an international outlook, echoing the earlier universalist framing of the International Sculpture Competition. The eagle should be viewed, he told one reporter, as ‘a symbol of freedom of man in general, not just a piece of pure patriotism’.45 But while such rhetoric might have flown in the early 1950s, it must have seemed wholly less persuasive by 1960, especially amid the anti-American sentiments in Britain that had been mounting since the Suez Crisis. Ironically, back in the United States the patriotism of Roszak’s eagle was targeted as ‘Un-American’ for the direction that its head faced – the opposite of most official heraldry.46 Such were the persistent contradictions faced by the artists and artworks that came to be entangled in the cultural Cold War, always unable to fulfill the competing and inconsistent visions of those who sought to shape what kind of art should represent the United States abroad.