June – July 1946

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth view John Singleton Copley’s The Death of Major Pierson, 6 January 1781 1783 (Tate N00733), purchased by the Tate Gallery in 1864, at the American Painting exhibition at the Tate Gallery. They are accompanied by John Walker, Chief Curator of the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (right) and Tate Director John Rothenstein (left). Published in London Illustrated News on 22 June 1946, p.7.

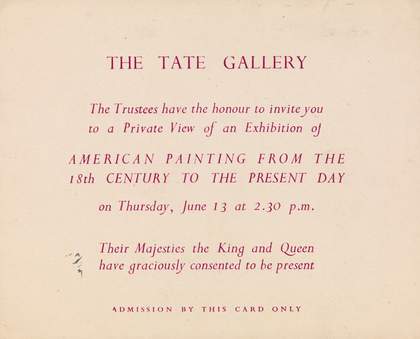

Invitation to the private view of the exhibition American Painting from the Eighteenth Century to the Present Day, Tate Gallery, London 1946

Tate Public Records TG 92/55/3

American Painting was the first major exhibition to be held at the Tate Gallery after the restoration of the bomb-damaged building. Organised by the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., it gave the British public what was later described as ‘its first opportunity of seeing something like the full range of American painting’.1

The show ranged from historical figures such as the Anglo-American painters Benjamin West (1738–1820) and John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) to such contemporary artists as Milton Avery (1885–1965), Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975) and Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986). Abstract expressionism had yet to establish itself as an international force in the way that it would do over the next decade (see The New American Painting exhibition in 1959). However, gestures towards this new direction were made with the inclusion of key figures in the movement such as Robert Motherwell and Adolph Gottlieb.

In her essay in this publication Caroline Riley argues that the purpose of the exhibition was ‘to articulate, at least in part, the complicated role of art in the interdependent historicising of violence and recovery of culture after the trauma of war’.2 She notes, too, that the gallery was unable to produce a more lavish catalogue because of a general lack of resources, including paper, in post-war Britain.