Otobong Nkanga giving her performance lecture at Tate Modern, 5 November 2019

© Guillaume Valli

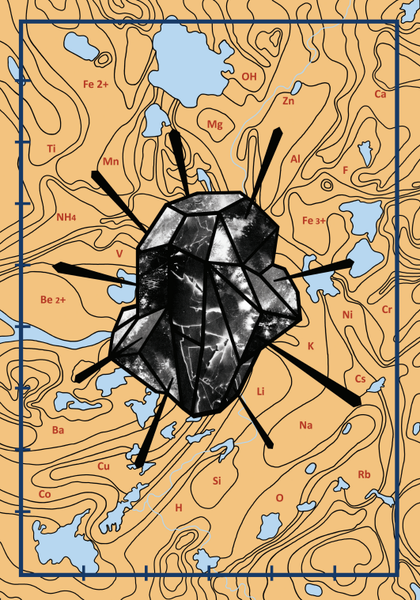

Nkanga’s practice centres around the relationship we have with the environment, mapping out ways in which we have damaged land, as well as its dependent ecosystems and communities. Her multi-disciplinary practice includes performance, painting and poetry, as well as sound and voice. As a way of activating a discussion about issues that are central to her practice, Nkanga began the performance lecture with the phrase: ‘I will start with the colour green’. Proceeding to recite a poem that focused on the colour, she opened up a conversation about the colours of the Nigerian flag, about health, identity and transnational migration, and finally about the relationships we have with the environment. The poem was recited against a backdrop of forty-eight photographic images from the series Post I and Post II, which include scenes of the Nigerian landscape devastated by a long history of geological extraction. The images include the ruins of concrete structures and buildings – which Nkanga later related to the colour grey – embedded within an immersive greenness of trees and bushes. By choosing these images, Nkanga was motioning towards a wounded landscape suspended in a constant state of ruination, signalling the historic and ongoing devastation of African land for the economic gain of large mining conglomerates.

The relationship between the politics of geology and the wounded Nigerian landscape recalls recent debates in academia about race and geology. This is most exemplified in the work of theorist Kathryn Yusoff, who states that geology pivots on an axis of racialisation and extraction, both of resources and of people, in what she calls ‘environmental racism’.1 Furthermore, artist and theorist Denise Ferreira da Silva’s idea of ‘blackness as matter’ offers a lens with which to read the environmental racisms that are overtly at stake in Nkanga’s work. In an essay titled ‘1 (Life) ÷ 0 (Blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞ / ∞: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value’, Ferreira da Silva discusses the relationship between blackness and geology by referring to Nkanga’s In Pursuit of Bling – Coalition 2014 (Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp). In this work and related performances, the artist explores her relationship with the mineral mica, which she frequently encountered and played with in her childhood.2 During the event, it became apparent that Nkanga’s view of the connection between blackness and geology is an apocalyptic one, and she described how she saw ‘blackness as the murmurs of what will happen in the future’. What this means is that the catastrophic, adversarial and strained way in which blackness has been forced to engage with the environment is catching up with the rest of the world. This is what Yusoff refers to as the Black Anthropocene.3

Otobong Nkanga giving her performance lecture at Tate Modern, 5 November 2019

© Guillaume Valli

Nkanga continued her lecture with a reading of Nigerian novelist Helon Habila’s text, ‘Elements’.4 Habila’s text, which appears in the exhibition catalogue for Nkanga’s St Ives exhibition, is separated into six parts – Fire, Water, Rock, Wind, Jewels and Earth – and is a fictionalised response to Nkanga’s photographic series, Post I and Post II. ‘Elements’ merges concerns of the abuse of land that are central to Nkanga’s practice with the narration of environmental devastation and ruin left by western companies in Nigeria, themes Habila explored in his 2010 novel, Oil on Water.5 Nkanga took deep breaths as she read Habila’s text. It was initially unclear to the audience whether these emphasised breaths were necessary for speech or whether they were deliberately hyper-audible to the audience. They appeared simultaneously calculated and intuitive – the artist seemed overcome with emotion at the gravity of the damage done to land, apparently needing to take extended breaths in order to compose herself and return to the task of engaging with the audience. Nkanga later made it clear that the breathing was a considered addition to the performance by explaining the importance of breath and air – their relationship to the body and to life as she engaged in a demonstrative meditation that culminated as a performative instruction of breathing. She hummed as she explained that it is the manner in which she breaths that potentiates the humming and that ‘makes the change from air to sound’. This focus on air and sound is exemplary of Nkanga’s use of different elements in her photography, performance, drawing and installations. Nkanga’s humming also relates to another key component of her work, the idea of song and sound as modes of healing.

Song and sound feature heavily in her performances, including Constellation to Appease 2019, which was performed for the exhibition in St Ives and involved a sculptural piece. She performed the piece in, to and for the sea, personifying it and allowing it to be the site, object and audience. She later took the sculpture that was part of the performance and suspended it on the ceiling in the interior of the museum space, thus fostering a material-based connection between the inside and the outside and bringing the Cornish landscape into the museum space. A short video clip of the performance was also positioned near the entrance the exhibition space, extending the interior/exterior traces.

Otobong Nkanga in conversation with Anne Barlow, Tate Modern, 5 November 2019

© Guillaume Valli

The performativity of Nkanga’s works was echoed most noticeably in the conversation between her and Anne Barlow. Seated facing each other, Nkanga and Barlow began by following the customary model for interviews, where Barlow asked Nkanga questions about her exhibition and broader practice and the artist responded. The conversation centred around the curator-artist relationship during the preparations for the exhibition in St Ives. They spoke about the many facets of Nkanga’s practice and centralised Nkanga’s sensitivity to issues of land, with particular reference to the Cornish landscape that formed part of the exhibition. What made the format of this interview different was the metre-long stick which Nkanga balanced between their bodies, connecting them physically as they conversed. The stick comprised elements that were reminiscent of a landscape, with trees on its top and a hanging pendulum rock below, echoing materials used in other works such as the installations Borrowed Light 2019 and From Where I Stand 2019. Throughout the conversation, Nkanga proceeded to shift position, acrobatically moving from the chair opposite Barlow to lying down on the floor in front of her. At one point she got up and stood behind Barlow, forcing the curator, who remained seated throughout, to change the direction of her chair in order to accommodate the artist’s new position. This performative element was comical, with Barlow struggling to anticipate the artist’s next move while trying to pose questions to her. Nkanga indicated the difference in priority between herself and Barlow, quipping that while Barlow was more interested in getting answers for her questions – which Nkanga answered satisfactorily at every turn – the artist was more concerned with what has happening with her stick. Most of the audience members laughed at this point and Nkanga informed the audience that the comedy was intentional – it was intended to demonstrate the layered, often strained and perhaps frustrating relationship between curator and artist during the planning of an exhibition.

It was quite apt for Nkanga to include a performance in a seemingly non-performative context such as an apparently formal interview, considering the quotidian nature of performance that she advocates. Nkanga mentioned at the event that she did not conceive of performance as a specific thing prior to her move to Europe – in Nigeria where she grew up, performance was part of everyday life and was not distinctive from any other mode of being. Performance was tied in with her daily life through the different ways in which she participated in church, interacted with uncles and aunts (as opposed to parents, siblings and friends), the way she engaged in traditional healing practices, and attended her local school. Through her interaction with Barlow, Nkanga enacted her belief that ‘performance allows for the possibility to share energy with others’.

Otobong Nkanga, Tate Modern, 5 November 2019

© Guillaume Valli

Speaking in the question and answer session towards the end of the event, Nkanga said of the performance lecture format: ‘It frees me’. She was able to follow the rules of a lecture that she wanted to follow, while discarding those that did not serve her purpose. She was able to move freely across the stage, throwing pieces of paper on the floor that she later picked up; she sang and hummed when it advanced her course better than speech; and she read a piece of fiction and some poetry to conclude the session. The evening successfully appealed both to those who might have had in-depth knowledge of Nkanga’s work and those less familiar with performance art. Nkanga brought her own personal story, humour and personality to the event, while keeping it intellectually and conceptually rigorous. The format also allowed the audience to benefit from hearing the artist speak about her work while witnessing aspects of the performative way in which the work is made manifest. Through the model of the performance lecture, we heard Nkanga’s voice, were engaged by her poetry, and listened to how she thinks with and through the land.