Introduction

This text aims to outline the methodology developed for acquiring Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain, a complex performance and film installation created by the artist, filmmaker, musician and teacher Tony Conrad in 1972. It is based on an internal document entitled ‘Methods for the Experiment: Testing the Dossier for Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain, Tate Liverpool’, written in May 2019 by Lucy Bayley, Pip Laurenson, Louise Lawson, Hélia Marçal and Kit Webb. The methodology was developed as part of the Andrew W. Mellon-funded project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum (2018–21) and focuses on understanding and testing what it takes to collect and conserve a complex performance artwork such as Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain (hereafter Ten Years Alive).1 The testing of the methodology took place during the week of 13–17 May 2019 as part of the work’s activation in Tate Liverpool, and a full account of how it was developed and tested is provided elsewhere in this publication.2

This essay presents a simplified version of the methodology that can be implemented into current conservation practices concerning complex performance artworks, and adapted to conservation processes for artworks that exhibit some sort of performative behaviour. This could include any artwork that is dependent on ritualised or scripted actions, such as installations, interactive sculptures, software-based art and performance art, among other forms. In addition to outlining the three stages of the methodology, this essay provides a bibliography of the texts consulted as part of its development.

Some aspects of this methodology are specific to the context of Ten Years Alive and its display and acquisition by Tate in 2019 and 2020 respectively. For instance, our research took place at the point of the performance artwork’s first display within the institution. In this document, we will be defining the minimum conditions needed to apply our methodology to other performance-based artworks. We will identify which elements are specific to the case of Ten Years Alive and the possibilities for adapting the methodology to artworks with similar characteristics.

Why a new methodology?

Ten Years Alive is a complex performance and multimedia work that includes the live performance of a musical ensemble and a projectionist. As mentioned, the work was created by Conrad in 1972, and was directed and performed by him multiple times before his death in 2016. The musical ensemble is complex, comprising two violins, a bass and a ‘long string drone’ – an instrument developed and made by Conrad himself. The projections include a film made by Conrad featuring a vertical stripe pattern that, when projected, creates optical illusions, an effect caused by the deliberate movement of the projectors throughout the performance.3

Conrad had multiple collaborators, often relying on local communities of curators, producers, musicians and film projectionists to expand the pool of performers wherever he was showing the work. Some of these collaborators participated in more than one performance of the work, while others were called in for a specific event. Besides building on the experience of handling and ‘playing’ the instruments and the projectors, the artwork’s manifestations were typically highly dependent on Conrad’s direction. This reflected his practice as a teacher, the relationships he established with the local artistic communities in the places the work was performed,4 and the authority embodied by the artist and the people whom he trusted.

The characteristics of this particular performance artwork make it especially challenging to document. On the one hand, Ten Years Alive can be considered non-delegated, meaning that the artwork was not created to be performed without the artist.5 On the other hand, Ten Years Alive was the first performance artwork to be acquired by Tate without the artist’s involvement in its acquisition and display. We were unsure if the documents we produced during this process would be enough to transmit such a complex performance, which had so many dependencies on implicit or tacit knowledge. By ‘transmit’ we are referring to the ways in which the information that is needed to activate the work can be passed on from generation to generation.

The methodology created by the Reshaping the Collectible project team and the time-based media conservation team at Tate aimed to explore whether the documentation that was created:

- Would be enough to transmit Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain.

- Could trigger moments of embodied learning.

- Would render the conditions for future realisations of the performance.

Using the methodology

This methodology can be adapted to test the documentation produced for conservation purposes for other complex artworks. The structure of the initial research design can be simplified and tailored to the specific needs of the institution and of the artwork to be documented. The focuses of your analysis can follow the stages identified in the methodology, but can be altered depending on your requirements; for instance, semi-structured interviews could be used to gather information on different experiences of a work, such as those of the performers or audience.

Methodology

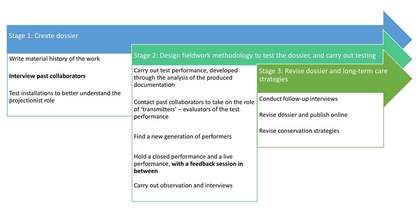

The methodology was developed in three stages: the creation of the documentation or dossier, its testing, and its revision (see fig.1). The following section offers a clear and detailed breakdown of each of these stages. The questioning form ‘What? Who? When? How? Why?’ is used to make it easier to adapt the methodology to other artworks, and this is followed by an outline of the outputs and resources relevant to each stage.

Fig.1

Diagram showing the methodology for developing the dossier

Image: Hélia Marçal, February 2020/November 2021

Stage 1: Create dossier

Write material history of the work

Interview past collaborators

Test installations to better understand the projectionist role

Stage 2: Design fieldwork methodology to test the dossier, and carry out testing

Carry out test performance, developed through the analysis of the produced documentation

Contact past collaborators to take on the role of ‘transmitters’ – evaluators test performance

Find a new generation of performers

Hold a closed performance and a live performance, with a feedback session in between

Carry out observation and interviews

Stage 3: Revise dossier and long-term care strategies

Conduct follow-up interviews

Revise dossier and publish online

Revise conservation strategies

STAGE 1: CREATION OF RELEVANT DOCUMENTATION AND/OR A DOSSIER

A dossier was created for Ten Years Alive that comprises a range of documents, audio files and video files that work together to create a fuller picture of what the work is and how to activate it.6 We made the dossier by gathering information through archival research and qualitative methods. The latter consisted of semi-structured interviews with past collaborators of Conrad’s in which we aimed to collect all available information about how to perform Ten Years Alive, focusing specifically on the collaborators’ interactions with Conrad and the material aspects involved in the work’s performance. Relevant information gathered from these interviews was then collated into the dossier. Within the dossier, the core element that links together all the different documents and files is the performance specification. The dossier was issued in advance of the performance to a new generation of performers who had never been involved in the work before, in preparation for Stage 2.

Below you can find the methodology for Stage 1, which can be adapted to other performance or performance-based artworks.

Detailed outline of Stage 1:

What? Creation of relevant documentation and/or a dossier.

Who? Conservation team or other teams responsible for documentation processes pertaining to the conservation of artworks, in collaboration with key actors, for instance the artist (or delegated representatives such as the estate or gallery), his collaborators and previous performers.

When? At the point of acquisition.

Why? To create and pull together key information about the artwork, drawing on a broad range of knowledge outside the museum that resides within the artist’s network; to ensure that there is clarity as to what the work is and how it might be activated.

How?

- Map when, where and how the artwork was performed. This includes identifying what equipment and materials were used and for what purpose; who has been involved in curating, producing, directing or performing the work; where the activations have taken place; and how the artwork was received and understood in the context of its activations.7

- Undertake interviews with key actors. The aim of the interviews is to document and develop an understanding of the work, including the similarities and differences between previous performances. Semi-structured interviews might be used for this purpose, and ideally they would focus on how people remember the work, their involvement with its activation and their own actions, and on understanding the material conditions needed to activate the artwork in a given context.8

- Test the installation as required in order to develop installation plans and guidelines. This would ideally happen in a dedicated space, but this will depend on the characteristics and size of the installed artwork. You may only need to test the components whose function and operation are yet to be fully understood. In the case of Ten Years Alive, for example, we focused on testing the set-up of the projectors.

- Capture the information gained from the test installation within a draft performance specification and add supplementary information to create a dossier.

Outputs:

- Dossier. The performance specification is the core document. Associated documentation can take the structure of guidelines.9 Documentation might include written testimony, observations and descriptions, written archival documents, video and audio files, and images.

- Research data.

- Testing of installation elements.

Resources:

- Staff time to book, prepare and conduct interviews, analyse the results, curate and archive data, and write up the dossier.

- Audio and video recording devices.

- Interview transcriptions.

STAGE 2: TESTING THE DOCUMENTATION AND/OR DOSSIER

This stage largely consists of a fieldwork experiment designed to test the documentation or dossier that has been developed. The fieldwork for Ten Years Alive brought together former Conrad collaborators that were associated with the artwork in one way or another, and a new generation of performers who had never performed the work. The activation of the performance for these two groups of people was documented using participant observation,9 semi-structured interviews and focus group methodologies.10

Below you can find the methodology for Stage 2, which can be adapted to other performance or performance-based artworks.

Detailed outline of Stage 2:

What? Testing of the documentation and/or the dossier.

Who? The new generation of performers, past collaborators, installation team, other members of staff (such as curators, registrars and conservators, where relevant), and the conservation team or other teams responsible for documentation processes pertaining to the conservation of artworks.

When? At the point of the first activation of the work.

Why? To map the gaps in the documentation and understand the need for alternative forms for transmitting information about the work.

How? The setting of the fieldwork experiment needs to accommodate the following conditions:

- Informed consent forms must be provided before the fieldwork research starts.

- The documentation or dossier should be issued in advance of the first day of installation or rehearsals to allow newly identified performers to become familiar with the artwork and their role. Six weeks in advance is ideal timing.

- At least two moments of rehearsal should be allowed for, where new performers are in contact with each other and with the other physical elements of the work. Time should be allowed for the new performers to test and start to activate parts of the work alongside their fellow new performers.

- New performers should carry out a closed performance. This will be viewed by past collaborators so that they can consider feedback and any alterations to the activation in advance of a public performance.

The fieldwork should be undertaken across the installation period, throughout the rehearsals and during the final performance. The fieldwork experiment consists of the following:

- Data collection. This can take on various formats, including:

- Video, for instance to capture rehearsals and performances.

- Audio recordings, for instance to capture discussions for transcribing.

- Photography, for instance to capture general shots of the installation and performance.

- Written notes, for instance to capture the moments of decision-making and observation.

2. Participant observation. This can include:

- Moments where interactions might have shaped the result of the observation, the performance or the documentation (autoethnography).11

- Discussions over the interpretation of the dossier.

- Discussions about any adjustments that need to be made to the dossier.

- Moments of revision, i.e. moments when performers or collaborators modify an action or behaviour within the performance.

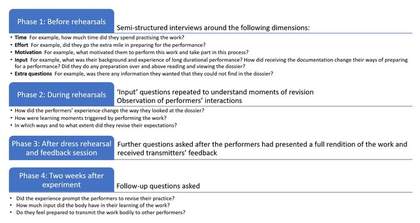

Fig.2

Diagram showing various phases of the interviews with the new generation of performers

Image: Hélia Marçal, February 2020/November 2021

Phase 1: Before rehearsals. Semi-structured interviews around the following dimensions:

Time. For example, how much time did they spend practising the work?

Effort. For example, did they go the extra mile in preparing for the performance?

Motivation. For example, what motivated them to perform this work and take part in this process?

Input. For example, what was their background and experience of long durational performance? How did receiving the documentation change their ways of preparing for a performance? Did they do any preparation over and above reading and viewing the dossier?

Extra questions. For example, was there any information they wanted that they could not find in the dossier?

Phase 2: During rehearsals. ‘Input’ questions repeated to understand moments of revision

Observation of performers’ interactions

How did the performers’ experience change the way they looked at the dossier?

How were learning moments triggered by performing the work?

In which ways and to what extent did they revise their expectations?

Phase 3: After dress rehearsal and feedback session. Further questions asked after the performers had presented a full rendition of the work and received transmitters’ feedback

Phase 4: Two weeks after experiment. Follow-up questions asked

Did the experience prompt the performers to revise their practice?

How much input did the body have in their learning of the work?

Do they feel prepared to transmit the work bodily to other performers?

- Interviews. In semi-structured interviews with new performers, you can try to channel your enquiries according to the following dimensions: input, motivation, time and effort.12 These interviews can occur at various different points, so that the learning moments of the new generation of performers can be identified (see fig.2 for an example of how we applied this to Ten Years Alive).

- Focus groups. Following rehearsals, try to hold a feedback session. Those present at the rehearsals and in the feedback session should include new and past performers, former collaborators, and relevant institutional staff, such as conservators, curators and installation technicians. The feedback session will review the performance and allow for corresponding changes to be made in the dossier. The following structure can be used for the feedback session:

- Free open feedback: an invitation to register first impressions of the rehearsal performance.

- Feedback from the performers: this will focus on what they felt were their personal contributions to the performance.

- Feedback from the past collaborators: this will focus on whether they deemed it an accurate presentation of the work and explore what indicators mark a successful production. Emphasis will be placed on what changes may need to be made before the public performance. These changes can be accommodated in the final dress rehearsal.

- Reflections on the documentation and dossier: did the dossier effectively communicate the work? What might need to be added or deleted?

- Feedback on the production: are there any aspects of the production (such as staging or sound design) that need to be altered before the public performance?

Outputs:

- Research data.

- One public performance (optional).

Resources:

- Staff time to prepare and conduct the fieldwork experiment, analyse the results, and curate and archive the data.

- Staff time to support the test performance/installation.

- Space for performing/installing the work.

- Audio and video recording devices.

- Storage space for collected data.

- Hired performers and consultants (depending on the artwork).

- Interview transcriptions.

STAGE 3: REVISION OF RELEVANT DOCUMENTATION AND/OR THE DOSSIER

Stage 3 of our research involved a critical review of the data gathered in Stages 1 and 2, including content analysis,13 with the aim of revising the dossier.

Below you can find the methodology for Stage 3, which can be adapted to other performance or performance-based artworks.

Detailed outline of Stage 3:

What? Revision of the relevant documentation and/or the dossier.

Who? Staff members who were involved in Stages 1 and 2, in collaboration with new and past generations of performers.

When? After Stage 2 is complete.

Why? The data collected from the feedback session, rehearsals and performance allows for reflection on what can be done to improve the dossier for future performers and maintain the dossier’s capacity to serve as a vehicle for the transmission of the work.

How?

- Read through the transcripts, notes and view any relevant video footage for comments or notes that would influence or change the documentation.

- Conduct content analysis for selected participant interviews via coding (segmenting and categorising parts of the interviews to identify patterns). This will lead to the identification of the key dimensions discussed with interviewees (for example, input, motivation, time and effort).

- Follow up with any queries or questions by holding interviews with new performers and past collaborators up to one month after the public performance.

- Make relevant changes to the documentation and dossier.

- Reflect on the long-term preservation of the work and update the conservation strategies that are in place for it.

Outputs:

- Research data. GDPR regulations should be followed at the end of the experiment.

- Revised dossier.

- Long-term preservation strategy.

Resources:

- Staff time to book, prepare and conduct interviews, analyse the results, curate and archive data, and revise the dossier.

- Audio and video recording devices.

- Interview transcriptions.