Fig.1

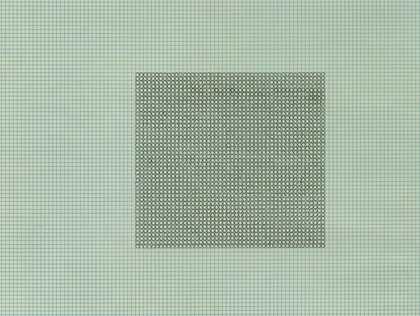

Lee Bontecou

Drawing 1961

Tate

© Lee Bontecou

In 1961 American artist Lee Bontecou (born 1931) produced Drawing, a large graphite pencil drawing measuring approximately one metre wide and seventy centimetres high (fig.1). Despite its substantial size, Drawing is somewhat sketchy in appearance, closer to a notebook doodle or small preparatory drawing than a finished work of art. Since the late 1950s Bontecou has used drawing both as a preliminary stage in the planning of her three-dimensional work and as an end product; both ‘work drawings and as drawings in themselves’.1

She has described how she frequently turns to drawing as a ‘fast fix’ that enables her to ‘work out problems in a piece of sculpture’ and from the outset has exhibited and sold her drawings alongside her sculptural objects.2

There were, however, other times when Bontecou would draw solely for ‘pleasure’, when she would indulge herself in a two-dimensional world of image-making tied not to the practicalities of the made object but to ‘the illusionary world of the magical pencil’, a world which Bontecou has described as ‘superlative’.3

Formally, Drawing shares much with the abstract imagery of Bontecou’s wall-mounted relief work for which she rapidly became known in New York during the early 1960s, with its black voids or negative ‘nothings’ puncturing the surface of abstract bulbous forms. In the drawing fluted crests and dotted lines curve out and away from the opaque black craters that populate the surface of the paper, while at other points geometric nets are faintly pencilled with a thin, delicate hand. A series of lightly framed fragmented segments, caught somewhere between mechanical drawing and a frozen explosion, arc concentrically from the voids, recalling the canopies of welded metal, stitched canvas and twisted wire that protrude from out and over the dark black cavities at the centre of her relief objects. Although better known for her work in three dimensions, Bontecou’s drawings share with her sculpture an investment in their materiality as objects. Specifically, Bontecou’s use of black both as sheer colour or ‘matter’ (for example, in the black blotches of pencil and soot she would often incorporate in her drawings) and as a means of demarcating the space – both positive and negative – of her line-bound forms.

At points the shadowy black cavities in Drawing have been smudged by Bontecou’s finger, so that the soft graphite areas are dirtied and blurred, contrasting with the outlines of intricate armatures and graduated shell and mollusc-like forms that scatter out from the centre of the paper like miniature diagrams or scientific schema. The central form in this drawing falls somewhere between futuristic spaceship and fantastical organ or unidentified body part, with the geometric crested segments jutting out and away as though a framing or scaffold support. The frequent appearance in Bontecou’s drawings of small insects, mouths and teeth, wings and even, in one remarkable drawing now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, a small, comical shark rising from arching wave-forms, allows the viewer to imagine the other, abstract shapes and forms as similarly anthropomorphic, as fleshy mounds or internal organs.4

The overall effect of Drawing does not, however, lie in its discrete parts, worked as they are to varying degrees of ‘finish’ and opacity, for at times the line is barely visible, appearing somewhat hesitant, while in other places the drawn line is thick and certain, where Bontecou has pressed the pencil hard into the paper. Instead, Drawing registers as a singular, specific object, reminiscent of a seashell, or an abstracted organic form.5

The series of small hole-like shapes punctuating the surface of the central object lend the form a sense of dimension and weight, implying it has interiority and depth, as though an object or body.

The carefully outlined drawn segments in Drawing peter out to barely visible marks and shapes; accidents, almost, that radiate from the centre of the landscape-oriented paper to the wide white untouched border, marked only by the artist’s distinctive signature and handwritten date at bottom right. The drawing, then, is finished and has been signed off by the artist as a complete work, or in Bontecou’s words, as an ‘illusionary world’ in its own right. What that world might entail is the focus of this essay. For despite its abstracted nature and handcrafted status as an artist’s drawing – produced at a time when the handmade and one-off were about to be usurped by the minimalist impulse toward serial repetition and the geometric line, there is something about Bontecou’s drawing practice that is nonetheless absolutely contemporary and of its time.

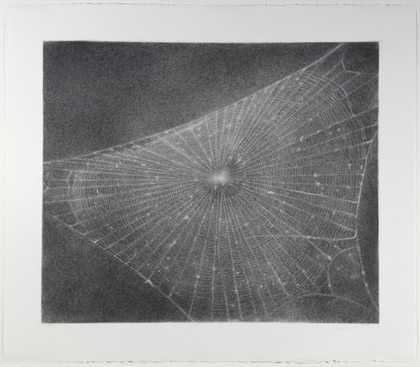

Eva Hesse

Untitled (1967)

Tate

Bontecou was not alone in producing drawings that challenged contemporary ways of going about imagining – and imaging – the world. Eva Hesse too, in her drawings on graph paper from the mid 1960s simultaneously combined the handmade and readymade; the faint wobbly lines of graphite that doodle in repeated series of circles belong as much to the world of mechanical repetition as they do to an intimate bodily process of pushing the pencil across the sheet of paper (fig.2). However, while Bontecou has declared an allegiance to the ‘magical pencil’ in her desire to capture ‘all freedom in every sense’ in her work, such expressive language was anathema to the younger Hesse, for whom an allegiance to the surreal and erotic was tempered by the monochromatic restraints of minimalism and the burgeoning process art moment.6

As art historian Benjamin Buchloh has recently noted, drawing underwent a number of significant shifts in the twentieth century, most significantly with the introduction of the Duchampian model of ‘anti-drawing’ in which Duchamp, along with a number of other artists, ‘converted’ the drawing strategies of the engineer, the architect, and the cartographer into one of the ‘new, suddenly emerging epistemes of drawing in the twentieth century’, to which, for Buchloh, Hesse’s serial yet handmade grid drawings belong. This shift was in part defined by artists moving away from representations of ‘the natural world’ towards what Buchloh describes as ‘a concept of drawing as the definition of technical and functional structures’.7

While Hesse and her contemporaries including minimalists Donald Judd8

and Sol LeWitt pursued to a greater or lesser degree a mode of drawing fitting Buchloh’s description, Hesse’s drawing practice was marked always by an ambivalence about the ‘technical’ and ‘functional’. At times her abstract-erotic recasting of the machine in her drawings shares more with Bontecou’s bulbous gaping forms than with the minimalist commitment to the geometric, demonstrating a shared hesitancy about such an investment that was, in Bontecou’s case, to become a mainstay of her practice in both two and three dimensions. In an early review of Bontecou’s drawings published in Metro critic Dore Ashton picked up on the mobile aspect of Bontecou’s drawings, in which her ‘evocation of the mechanical engineers’ drawing board, replete with joints, nuts, bolts and other hardware’ becomes ‘transformed’ in her drawings into ‘human limbs, and visions of nightmare’.9

Drawing, with its part-machine, part-biological structure is at once archaic and futuristic. Its decidedly open system of representation harks back to an earlier biomorphic mode of representation, recalling early twentieth-century abstraction and surrealism. A little closer to home, Drawing, with its pseudo-scientific forms and references to the organic and natural world evokes contemporary ecological politics and environmental concerns – think of Buckminster Fuller’s post-war geodesic architectural fantasies, or the architectural and eco-projects of San Francisco collective Ant Farm in the late 1960s and 1970s. In fact, between 1969 and 1970 Bontecou made a number of futuristic giant plastic plants, with gas masks instead of stamens and trailing cords in lieu of leaves. Bontecou’s plant works were executed in two and three dimensions, and a number of startling figurative drawings of plants and natural forms began to dominate her practice from the late 1960s onwards.10

The plants register as horrific harbingers of a future with no clean air or natural life, and the artificial plastic of the flowers contrasts sharply with the attendant suggestion of organic material. The plant forms bring to the fore ecological concerns that had haunted Bontecou’s earlier abstract references to the natural world, rendered ambiguous in her wall relief objects, where the industrial and mechanical appearance of the reliefs, made from natural fibres and skins such as leather and canvas, are pulled taut against the welded metal framework that hangs from the work and which contains that central void – at times barred with appropriated metal saw teeth, sawn-off sections of piping, grommets and reclaimed metal grilles.

The blackened mechanical remnants and forms that similarly comprise the drawing Drawing call to mind the grunginess of Bontecou’s environment during the 1960s – from the ex-industrial lofts she lived and worked in, first on the Lower East Side on Avenue C and, by 1963, SoHo’s Wooster Street – to the hardware and junk stores of Canal Street from where she, along with many of her peers would scavenge for nails, paint supplies and other manufactured and found oddments to include in their assembled junk objects. These material objects haunt the abstraction of Drawing, for while they structured Bontecou’s sculptural imagination throughout the early years of the decade, they also left their traces among the smudges, fingerprints, cavities, and makeshift scaffold forms and industrial-looking objects that appear in her drawn worlds. The opposing sets of formal interests embodied in Bontecou’s works – her references to both the natural world and the man-made environment – are precisely what gives her work its peculiar status as both absolutely of its time and at the same time somehow archaic in its references and investments. The two spheres are not in conflict in Bontecou’s drawing but rather are bound intimately together.

Caught part-way between architect’s drawing and unconscious doodle, Drawing spans the range of different ways in which drawing has been typically understood, from its supposed ability to reveal the inner workings of the artist-as-subject, its classification as ‘minor’ or preparatory art form, to its status as the most ancient or primordial of artistic media. When Vasari described the artist’s sketch as a ‘first drawing’, his word for that initial act of mark making was a ‘blotch’, calling to mind the very first marks or ‘rough draft’ the artist makes on the blank surface.11

Drawing, in all its various forms – and materials – has traditionally been located at the origins of how the work of art is begun, from the famous cave drawings at Lascaux in south-western France to the eighteenth-century fascination with the eponymous narrative of art’s beginnings, when Dibutades outlined the shadow of her lover as it was cast against a dark wall, creating one of the earliest ‘illusionary worlds’ in the history of art.12

Meanwhile, writer and artist Deanna Petherbridge has argued for the ‘primacy of drawing’ as a medium precisely because, unlike the ‘relatively closed systems’ of painting or sculpture, drawing ‘is open to appropriation, both as act and subject’.13

For Bontecou, drawing allowed a free-play of association and reference between abstraction, expressionism, the natural world and the urban environment (she would at times include sketches of old gas masks, engines and other everyday items in her drawings). Bontecou allowed figuration to take a more prominent role than it did in her consistently abstract sculptural works, while accommodating, too, the abstract voids, curvilinear forms and feathery pencil strokes that evoke the beating of an insect wing, or a thin skin-like membrane. In some drawings Bontecou included eyes and teeth, although it is in her abstract drawings such as Drawing that the full force of her drawing strategy is most keenly felt, for it is in works such as these that we witness Bontecou’s resistance to figuration, to the world of representation, even while we see it pushing back and threatening to break through. In Bontecou’s drawing the motifs of the natural and man-made, the urban and pastoral, the real and the fantastical interlock. For while her sculpture has taken primacy in many accounts of her work, Bontecou’s works on paper are far from straightforward exercises or preparatory sketches. On the contrary, they are deeply felt, if ambivalent, statements about the world. They invoke entirely distinct (and distinctive) contradictory worlds of their own; worlds that are both out of step with the contemporary environment within which they were both produced but also inescapably of a piece with it.

Bontecou’s description of the kinds of issues she fought to hard to address in her abstract works is summed up in a recent statement by the artist in which she recounted how heavily they weighed on her mind – and practice – during the 1960s: ‘The most persistent recurring thought is to work in a scope as far reaching a possible, and to express a feeling of freedom in all its necessary ramifications. The biological world-aircraft – train systems – landscape space – world events (am afraid mostly the underbelly of human nature and the horrible global mess this little planet is in) and of course ones’ own inner world mixed in as well as imagination.’14

Mixed with a futuristic vision of the ‘biological world-aircraft’ is that ‘horrible global mess’, the dirty underside of a utopian modernist vision to which her drawings so eloquently and abstractly speak. Drawing, then, can be a dirty business. Bontecou makes this clear when she smears her soft graphite scribbles, leaving faint fingerprints on the pristine paper, or where she uses an eraser to make corrections. Bontecou’s drawings are a palimpsest of previous marks made, for the indent of the pencil tip remains physically embedded in the thick paper, just as the remnants of soft pencil dust remain not so much eliminated as moved and pushed around the page. Bontecou exploits the dirtiness of drawing by allowing the pencil dust to be made mobile, whether by moving it across the paper with her finger or, most vividly, when the artist elected to produce drawings incorporating soot.

Bontecou understood the term ‘drawing’ in pretty capacious terms that covered all of her works on paper whether they included soot, graphite, or other materials. In 1962 Bontecou produced a series of lithographs at Tatyana Grossman’s Universal Limited Art Editions comprising large expressive black voids, ringed by concentric smudgy circles of muddy taupe and soft grey that vividly recall her three-dimensional wall-relief sculpture. Lithographic printing tends to be favoured by artists not trained in printmaking, as it requires far fewer specialist skills such as engraving with a special burin. Instead, the artist draws freehand over the surface of the lithographic stone with a wax crayon, which in turn allows for large areas to be fairly quickly voided or rendered ‘negative’ in the final printing. Bontecou was assisted at Universal by the poet Tony Towle who had been hired by Grosman the same year, on the recommendation of his friend the New York School poet Frank O’Hara who had also worked on a series of prints with artist Larry Rivers at Grosman’s studio in 1957 called Stones (Bontecou’s series was also named Stones, after the medium on which the lithographs were produced). Bontecou’s prints, which are numbered consecutively, feature a large dense black area, from which radiate fainter black shadows which resonate from the centre of the page and out. The large gaping cavity, which Bontecou would have blocked out entirely in wax on the lithographic stone, achieves the opacity, or blackness, that was never quite attainable in the soft graphite she had been using previously. Rather, this series shared more with Bontecou’s experiments in drawing with soot, which the artist first embarked upon in the late 1950s and to which, in the early 1960s, she returned. It was in fact during Bontecou’s interview with Towle that she first referred to her soot drawings as resembling ‘a worldscape sort of thing,’15

and in so doing evoked something of the air of mystery and open-endedness she so often conjured up when describing her work, pointing in particular to her frequent motifs of the large black void or ‘blotch’ which, whether incorporated literally in her large three-dimensional relief objects or illusionistically with the thick swathes of soot or densely-worked craters and cavernous holes she produced using a soft graphite pencil.

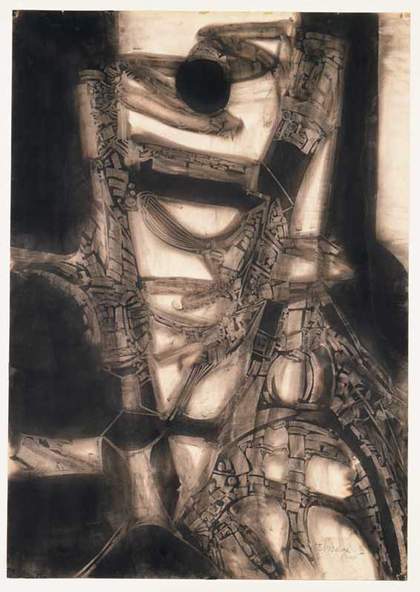

Vija Celmins

Web #1 (1999)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Bontecou made her first drawings using soot between 1956 and 1958, while working in Italy on a Fulbright scholarship. However, to describe these works as ‘drawings’ is to stretch the term to its very limits, for Bontecou dispensed with all of the usual materials with which a drawing is typically made, using nothing other than a blowtorch. Bontecou’s soot drawings, like her contemporary Vija Celmin’s bone-grey pencil renderings of spider webs or the night sky, appear as if they have been scraped into the pencil ground, etched into the surface to reveal the white sheet of paper beneath.16 Celmin’s recent charcoal drawing Web 1 (fig.3) is a dusty drawing of a spider’s web that calls to mind Bontecou’s spiny, web-like matrices and similarly sooty treatment of pencil and the drawn line. Like Bontecou’s soot works, Celmin’s drawing works by negative means, and the white gossamer-thin web is barely distinguishable from the soft graphite background, appearing as the most delicate of images; as though a photographic negative or image captured at night, emerging from the black, a shadow on the wall, cast in dusk-like light.

Fig.4

Lee Bontecou

Untitled 1958

Soot and graphite with areas of erasure and resist on cream wove paper

990 x 690 mm

Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Dr Alvin E. Friedman Kien

© Lee Bontecou

Bontecou realised while working on her earliest welded metal sculptures that if she turned the oxygen down on her welding torch thick clouds of soot poured from where the gas flame should be. As she later recalled: ‘I discovered by closing down the oxygen on my acetelyne oxygen tanks I could create a beautiful black line or mass by moving the torch very quickly across the paper or canvas. I used the black soot in many forms, and did quite a few soot drawings in conjunction with pencil – but most important I found a real black that one could sink into or enter’.17 Bontecou decided to experiment with this accidental discovery, and alongside incorporating soot into her sculptural objects, which she used to dirty the rims of the cavities and depth and shadow she produced a number of drawings in which she guided the welding torch carefully over a thick sheet of paper, covering it entirely with wide horizontal bands of velvet-black soot in graduated waves. The landscape orientation lends the works the appearance of some kind of horizon line – a lunar landscape or seascape, perhaps. In Untitled 1958 (fig.4) Bontecou worked the soot across the surface in a highly complex way, using tape to produce channels and caves, ladders and holes of black matter, scraped and scratched across the metre-long paperboard with a razor blade. Prefiguring the later use of velvet-black voids and cavities in her wall relief and drawing work, the blanked and scratched out areas of both black and white again recall the attraction of negative space. ‘Getting the black opened everything up’, Bontecou declared: ‘It was like dealing with the outer limits’.18

Bontecou’s works seem always to invoke a world beyond their limited material conditions, something critics and viewers alike have recognised from her earliest exhibitions. Indeed, Bontecou was not alone in insisting on her works’ polyvalent status. Since the early 1960s an extraordinary range of metaphors have been employed to describe Bontecou’s sculpture and drawings, from the monstrous ‘vagina dentata’ to ‘air conditioning units’ as O’Hara’s peer and fellow New York School poet John Ashbery described them in 1966. Other commentators have compared her three-dimensional metal and fabric reliefs with their large black holes protruding from the frame to flowers, spaceships and machines in flight, with one particularly imaginative review querying: ‘Is it a pterodactyl? A Flash Gordon spaceship? An outsize artichoke or a monstrous whorl of giant flower corollas?’19

While a playful description, the reviewer’s point here is a good one: it is never entirely clear where Bontecou’s allegiance lies, nor to what aspect of the world – man-made or natural, archaic or contemporary, ‘real’ or imaginary – her work is most closely tied. Bontecou’s drawings perform a curious kind of anachronism. They look back to the earlier abstract-expressive gestures of the 1940s and 1950s, and forward, with their use of new, non-art materials, and references to the contemporary urban environment. For every commentator who sees flora and fauna, ‘feminine imagery’ and outer space in Bontecou’s works on paper, there is another for whom its dynamic charge is attributed to its connections with sputnik and war, with planes and flight, machinery and weaponry. While neither reading is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, neither is quite sufficient nor up to the task of accounting for the appearance nor charge of her drawing practice as it has taken shape since the late 1950s.

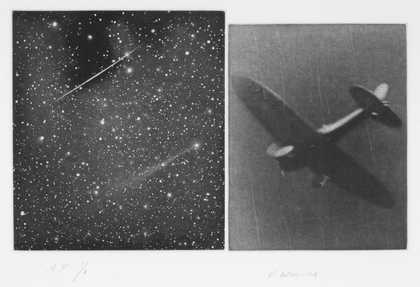

The natural world has always remained a constant source of inspiration and interest to Bontecou; even when ensconced within the urban environment of New York City’s art world she would vividly recall her childhood summers spent playing outdoors, fishing and playing among the deserted and expansive mud flats and coastline of Nova Scotia, where she would play in the world’s first aluminium canoe, a cutting-edge invention designed by her father. Yet for all their references and allusions to the natural world, flight and outer space, it seems to be no coincidence that Bontecou was producing these drawings while living in Manhattan. For despite their heady aspirations, the material of the drawings – the blown soot, the smudged pencil, the scraped damaged areas of inky residue – remain firmly rooted in the grimy and industrial world of downtown New York. Bontecou’s use of soot and smudging – that is to say the ‘dirtier’ side of her drawing practice – tends not to be discussed very much when her drawings are written about. Perhaps their frequently overt references to the natural world somehow forestall such explorations with commentators preferring to take the artist at her own word, to search for the freedom and openness of expression upon which Bontecou has always insisted. However, a consideration of those aspects of her work that are firmly entrenched in her contemporary urban environment, even as she looked back, up to the skies, or away from the city is now timely; particularly given her early concerns regarding the damaging impact the modern world inflicts upon the natural one. Yet it is the movement between the natural and man-made that is a key structural imperative of Bontecou’s drawing practice, that ‘fast-fix’ back and forth that describes too her incorporation of such divergent worlds on the same drawn page. For all Bontecou’s investments in the natural world away from the urban environment of the city (her Wooster Street loft was based above a large laundry from where she would scavenge old sections of driers, fabrics and other industrial objects), her drawing practice remains nonetheless deeply entangled with each, and it was in Manhattan that she first began to experiment with those drawings and later plastic sculptures that explicitly referenced the insects, birds and products of nature even as they appear tinged by the environment out of which they came. Celmins, too, has employed this kind of formal disjuncture in a recent work on paper in which she pairs a detailed etched depiction of the night sky with an equally detailed rendering of a blurred photograph of a military plane in the sky (fig.5). Celmins, like Bontecou, has always been fascinated by flight – during the 1960s Bontecou produced a series of circular drawings inspired, she said, by the view of the plane engine during a flight. Bontecou even incorporated a section of an old World War Two bomber plane into one of her more ambitious relief sculptures in 1964, a large totemic work that, like her drawings, awkwardly combines the natural and industrial, the handmade and the technologically advanced.

Vija Celmins

Concentric Bearings B (1984)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

In his 1954 poem ‘Meditations in an Emergency’, Frank O’Hara evokes a similarly ambivalent account of the city dweller’s relationship to their environment to that invoked by Bontecou, writing how ‘One need never leave the confines of New York to get all the greenery one wishes – I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy. Or a record store’, the line continues, ‘or some other sign that people do not totally regret life’.20

O’Hara wrote this poem during a brief hiatus from working at MoMA, where he had previously worked at the front desk, before returning to the museum in 1960 as a curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpture.21

Like Bontecou, O’Hara embraced the ordinary and everyday in his writing, even as he heralded those painters for whom large-scale abstraction and an attendant, often spiritually inflected language of ‘freedom’ provided a necessary escape from everyday, lived experience. O’Hara, like Bontecou, accepted the conflicting nature of the city and country, the pastoral (a word used frequently in connection with abstract-expressionist painting) and the urban. The year Bontecou made her first soot drawing, O’Hara wrote Song,in which O’Hara turned his attentions from the Whitman-esque ‘blade of grass’ to the rather dirtier environs of the subway and street, obliquely invoking too a blurring or freewheeling between the ‘dirtyness’ of the city streets and the ‘dirtyness’ of the subject’s mind:

Is it dirty

does it look dirty

that’s what you think of in the city

For O’Hara, thoughts, objects and people become dirty in the city: ‘run your finger along your no-moss mind’, the poem continues, ‘that’s not a thought that’s soot.’ From O’Hara’s invocation of a clean ‘no-moss’ mind to Bontecou’s desire to ‘mentally scrape’ her viewers, the kind of ‘worldscapes’ Bontecou and O’Hara conjure are tied intimately to the environments in which they were produced.22

As has recently been noted, part of the success of O’Hara’s vision of New York is that, while it is romantic, ‘it is not too romantic. The hot-dog stands and car-repair places attracted him as much as or even more than the shining skyscrapers.’23

For Bontecou also, there is a desire to capture something of the contemporary as well as a poetic, expressive language of description (‘all freedom in every sense’) that seems to belong to an earlier aesthetic moment, and in invoking both the urban as well as the natural world in her drawing practice, she demonstrates how one might cast the other into a different light, or maybe shadow. Bontecou’s desire to ‘go for miles into the surface’ in order to ‘get to black’ invokes a world that looks both up and out into the far reaches of the natural world, into outer space and the future, and down, to the contemporary, urban environs where she – and the objects she depicts, makes and imagines – remain rooted.24

The fantastical and imaginary become material and mute, specific, blackened marks, stains and remaindered material residue: ‘that’s not a thought’, O’Hara continues, ‘That’s soot’. For all their ambitious attempts at capturing the natural world in all of its enormity, Bontecou’s drawings remain committed to the materiality of graphite, carbon and soot. It is as if Bontecou’s drawings desire to capture nothing at their heart – a kind of blankness that is both resolutely material and formally intangible, close in spirit to O’Hara’s playful shift in register and significance from a ‘thought’ to ‘soot’. Bontecou’s investment in black is a mainstay of her practice in both two dimensions and three, and its constant presence is worth pausing over. Far from registering simply as a ‘nothing’, there seems to be, for Bontecou, a freight of significance to her choice of soot-black voids.

‘All freedom in every sense’ was Bontecou’s own description of what she hoped to capture in her work: a rallying cry for a mode of art making that seems far removed from her contemporary milieu of assemblage art and the production of objects rooted explicitly in the contemporary, urban environment of downtown Manhattan. In fact, like her contemporary John Chamberlain, Bontecou allied her working practice not to that of her assemblage peers (which, given the appearance of her sculpture at that time, comprised of welded metal frameworks covered with rough and recycled patches of reclaimed fabric, is somewhat surprising), but to the work of an earlier generation of abstract-expressionist artists, who ‘gave young artists a burst of energy and a desire for boundless freedom to break away’.25

‘Abstract expressionism I loved’, Bontecou said, ‘real painting mixed with an excitement of feelings. Pop art I had no interest in. It brought down the house of expressionism and cut its life span too short’.26

Bontecou’s investment in the obsolete, the dirty, stained and industrial is a world apart from the loftier ambitions of the abstract-expressionist artists she so openly admires – far closer in fact to the Pop art, assemblages and found objects of her New York City-based peers including Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Niki de Saint-Phalle and Jean Follett. In her combination of bombastic proclamation that remains better suited to the earlier generation of expressionists, and her contemporaneous interest in the grimier side of urban life, Bontecou’s drawings – in their search for ‘all freedom in every sense’, seek to establish some common ground between these two approaches to figuring the world through abstract means. Drawing, then, was an intermediary device for Bontecou – although not between ‘thought’ and ‘object’, but between abstraction and representation, between an ideal world and the lived environment within which the drawings were conceived and produced. It is for this reason Drawing remains such a striking drawing, for it cannot be pinned down as either one thing nor the other – neither finished work nor preparatory sketch, neither abstract form nor representational, neither natural nor man-made, real or imaginary it, instead, places each of those opposing categories under pressure, united through a shared reliance on black as structuring principle and material support.

In 1970, around the same time Bontecou left New York and, by most accounts, the New York art world. Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory was first published in German. In a section of this book dedicated to colour, Adorno wrote in defence of ‘black’ – a colour he considered wrongly maligned by contemporary artists in favour of a much brighter – for which read kitsch – palette and series of sounds. What is at stake for Adorno are the various ways and means by which artists could – and should – go about representing the world not as a utopian promise or mere spectacle. Rather, in order to ‘survive reality’ the work of art must address or capture that ‘reality’ at all costs. Adorno’s claims are suggestive of precisely the seriousness with which Bontecou’s drawing practice might be associated, in which she worked so hard to ‘get to black’. In fact Adorno’s assertion that ‘To survive reality at its most extreme and grim, art works that do no want to sell themselves as consolation must equate themselves with that reality’ reads also as a fairly accurate account of Bontecou’s deep commitment to art’s radical possibilities – even at its most abstract – to somehow figure or comprehend the world. ‘Radical art today is synonymous with dark art’ Adorno continued, and ‘its primary colour is black’.27