The early 1950s was a time of considerable change for the British sculptor Barbara Hepworth. Her marriage to Ben Nicholson was dissolved in October 1951, her son Paul Skeaping died in 1953, and the experience of visiting Greece for the first time in 1954 had a profound effect on her work, leading to a notable series of carvings in Nigerian-scented guarea wood. These facets of Hepworth’s life and career have been well documented, but to date little has been written about another aspect of her professional life during this period: her relationship with the commercial gallery Gimpel Fils in London.

Scholarly interest in the mechanisms of the commercial art world has increased over recent years and there is a growing body of literature charting the histories of a number of selected British galleries and dealers.1 That the art market was founded, and functioned, on the basis of personal relationships between specific artists, dealers, collectors and critics may be acknowledged, but detailed analyses of the interactions between these agents are still rare. Examining the circumstances in which Hepworth joined and left Gimpel Fils, this paper charts the vicissitudes of a specific artist-dealer relationship between 1954 and 1972.

Hepworth was already fifty-two years old when she joined Gimpel Fils in 1955, and she had firm ideas and expectations of what a commercial gallery should provide for an artist of her stature. She knew that a regular exhibition in a commercial gallery not only ensured an outlet for the sale of her work but also guaranteed that new work could be shown to networks of critics and curators. Records held in the Gimpel Fils Archive reveal the complex negotiations she undertook to secure the terms of her contract with the gallery, as well as her involvement in the processes of exhibition-making. Her decision to work with Gimpel Fils is revealing because of the way in which she developed a close friendship with brothers Charles and Peter Gimpel, who had founded the gallery in 1946, and with Charles’s wife Kay, who was the gallery’s manager. As art historian Robert Jenson has observed, ‘private galleries offered more than one-person shows and business management’.2 Indeed the Gimpels can be identified as ‘ideological dealers’, interested in more than just financial matters.3 Hepworth felt overshadowed by leading male artists of her generation – Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore and Naum Gabo – but the Gimpels recognised her importance to the development of British modernism.

Fig.1

Ida Kar

Charles Gimpel and Peter Gimpel 1958

National Portrait Gallery, London

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Born in France, Charles and Peter Gimpel (fig.1) were the sons of René Gimpel, a Parisian art dealer, and Florence Duveen, the youngest sister of the British art dealer Joseph Duveen. 4 Both brothers had had distinguished careers during the Second World War and on establishing their gallery in London in 1946 they settled on the French name Gimpel Fils – Gimpel Sons – in tribute to their father, who had served in the Resistance and had died in early 1945 at Neuengamme concentration camp.5 Prior to the war, some of René’s gallery stock had been shipped to London for safe-keeping, and it was with the sale of these paintings that Charles and Peter financed the gallery in its early years.6 The first exhibition held at the gallery in November 1946 was titled Five Centuries of French Painting, and contained works of art by Fragonard, Chardin, Monet and Degas. During the 1920s the Leicester Galleries in London managed an exhibition programme made up of historic and contemporary works to ensure economic stability, and Gimpel Fils followed this pattern of dealing in old masters and European modernists in order to fund its programme of financially risky exhibitions of new art until the late 1950s.7

Although economic factors compelled Gimpel Fils to exhibit the gallery’s stock of French art, the brothers were staunch advocates of abstract, non-representational art. When Hepworth joined the gallery they already represented fellow St Ives artist Peter Lanyon, the painters Alan Davie and Sandra Blow, and had established a preference for modern British sculpture, exhibiting works by artists including Robert Adams, Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Bernard Meadows, Henry Moore and Leslie Thornton.8 In their decision to work with selected artists and champion a particular type of contemporary abstraction, the brothers can be identified as ideological supporters of modernist art. Jenson has observed that ‘what separated the ideological merchant from his brethren was the claim to be dedicated not merely to making money, but to be an advocate of a particular kind of art, held above all others in the name of its “authenticity”’.9 In 1973, at the time of Charles Gimpel’s death, Helen Kapp, Director of Wakefield City Art Gallery wrote:

Dealers are often denigrated – Charles Gimpel was one of those whose integrity was immaculate; whose sensitive feeling for all forms of art was superb and whose judgement was most discriminating. He never stinted of his help. His kind, perceptive and realistic guidance to art directors of provincial museums, who, like myself, were interested in contemporary art was encouraging and disinterested.

He was generous to a fault, and with his brother Peter, his concern with living artists themselves, helping them financially, and showing discerning faith in their work, must have been one of the most important factors in the lives of many established artists of today, to the great enrichment of us all.10

Although the artists who exhibited work at Gimpel Fils during the 1950s are today firmly established within narratives of modernism, in 1960 Peter Gimpel recalled that in the early years of the gallery’s history ‘people shouted insults at them through the door’.11 This hostility and the limited audience for contemporary art translated into a limited client base. In an interview with the Sunday Times in 1960 Peter Gimpel suggested that British taste was forty years behind artistic developments and that the Royal Academy had stifled the British people’s appreciation of modern art; he noted with some regret that ‘only a dozen of our customers are British’.12 In the early decades of the gallery’s history many of its clients were North American, including Peggy Guggenheim, Joseph H. Hirshhorn and Raymond Nasher. Nonetheless, according to art historian Roger Berthoud, the 1950s was the decade in which Gimpel Fils flourished, and ‘despite the rise of Marlborough Fine Art and stiff competition from the likes of the Redfern, Waddington and Hanover galleries, Gimpel Fils was for a time unrivalled in the range and quality of its artists’.13 By 1960 Gimpel Fils was, according to the Sunday Times, a ‘very firmly established avant-garde gallery’, an assessment that was surely based in part on the work and reputations of the artists they exhibited.14

Hepworth’s marriage to Ben Nicholson ended in October 1951, but despite their separation they continued to work side by side in St Ives, and it was Nicholson who facilitated her move to Gimpel Fils. In a letter dated 1 December 1954, Nicholson informed Peter and Charles that since his last show at the London gallery Reid and Lefevre had not sold well, and because the gallery had decided to concentrate its activities on French masters rather than on contemporary British art, ‘I felt I might look elsewhere for my next show’.15 He noted that he and the director Alex Reid had discussed the matter and the decision to part company had been made on friendly terms. He enquired whether the Gimpels might like to visit St Ives to discuss working together and added, ‘as you know Barbara Hepworth recently parted company with Lefevre for much the same reason and on the same amicable terms’.16

Hepworth had worked with Reid and Lefevre during the 1930s and had exhibited with them four times between 1946 and 1952 (these exhibitions had been staged on a show by show basis, with no contractual obligations for either party). She nonetheless saw the commercial sector as paramount for both the maintenance and prolongation of her critical and financial success and by the time she joined Gimpel Fils was used to having regular exhibitions in London. According to the curator Bryan Robertson, Hepworth felt she needed to find a new gallery in 1954 because:

the senior partner in the Lefevre Gallery, Duncan Macdonald, who loved her work and showed it with enthusiasm, had died, leaving a gallery that was now indifferent to her work and had decided to cut out shows of contemporary art and concentrate on its renowned stock of French pictures. She had been told that sculpture and sculpture bases messed up the carpets of the gallery.17

Against this backdrop it was important to find a dealer who was receptive to the aesthetic and intellectual aims of her practice. The Gimpels’ earlier support of both Nicholson and Hepworth had been an influencing factor in their decision to approach the gallery.18 As Nicholson said in his letter of 1 December 1954, ‘you’ve been so friendly and appreciative of my work + it is not only sales, important as these are, which an artist looks for’.19 The Gimpels responded positively and enthusiastically to Nicholson’s overtures and it was agreed that Charles would go down to St Ives for a meeting.

At this time Gimpel Fils was only eight years old and therefore still a young gallery, which up to this point had specialised in the work of young artists. Indeed, Nicholson queried whether Gimpel Fils would even be interested in working with established, older artists, writing, ‘maybe your policy is to handle only the younger artists’.20 Although the chance to represent Hepworth and Nicholson had come unexpectedly, the Gimpels nonetheless seized the opportunity. The cultural capital and prestige gained by working with both artists would not have been lost on the brothers and the gallery’s status would have risen by such an association. Business relationships with Hepworth and Nicholson would give Gimpel Fils access to their pre-existing clients, supportive critics, and connections in regional and international galleries, all of whom could potentially be cultivated to support the gallery’s younger artists. Charles travelled to St Ives and met with Nicholson on 12 December and with Hepworth the follow day, discussing terms of agreement with each artist individually. Written contract negotiations between Gimpel Fils and Hepworth commenced on 1 January 1955. In a letter to Hepworth, Charles outlined the terms of their agreement: Gimpel Fils would become Hepworth’s ‘official dealers’, exhibiting and selling her work from the gallery, receiving 33⅓% commission on all sales. As curator Alexandra MacGilp has noted, this was the commission percentage used by Arthur Tooth & Sons during the 1920s, and by the 1950s had become an industry standard.21 Although Gimpel Fils became Hepworth’s official dealers, they did not have exclusive control over the sale of her output and she continued to make private sales direct to clients from her studio. It was agreed that Gimpel Fils would not take any commission on these sales unless the client in question had been introduced to her by the gallery. The gallery agreed to hold regular solo exhibitions of Hepworth’s work and to present it in displays of gallery stock, and agreed to underwrite the costs of staging an exhibition, including the publication of promotional materials such as catalogues, while Hepworth agreed that she would be responsible for paying the costs of transporting her work from her studio in St Ives to London. In addition to their commission, the gallery was able to buy a work for its stock at half the agreed retail price. As the person who was most familiar with the recent sale prices of her work, Hepworth set the prices of the sculptures included in her first exhibition, but the Gimpels later advised her on price structures.22

With regard to the promotion of Hepworth’s work nationally and internationally Gimpel Fils agreed to undertake the administration and co-ordination of all exhibition loans and sales to dealers within the British Isles and foreign galleries, with the exception of the USA. Prior to joining Gimpel Fils, Hepworth had entered into an agreement with the New York-based Martha Jackson Gallery, which was already organising Hepworth’s large-scale 1955–6 touring exhibition of North America. Gimpel Fils agreed to work with Martha Jackson, not only to ensure the best possible representation of Hepworth’s work but so that the two galleries did not find themselves in competition with each other for sales. Charles Gimpel concluded his letter outlining the terms of the agreement by writing, ‘we will endeavour by all means possible to display your work both in our Gallery and outside to your very best advantage and in keeping with your position as one of Europe’s most important sculptors’.23

Initially Hepworth was very pleased with this arrangement, responding to Charles’s letter on 6 January 1955 stating, ‘I look forward so very much to our association and collaboration’.24 The contract gave her the security of a regular exhibition and agents dedicated to the profitable sale of her work, and the freedom to continue selling her work from her studio, as she had always done. However, she did ask whether the gallery would consider a number of points. Firstly, that her sculpture would be insured while on the gallery premises so that if a work were damaged money would be forthcoming to pay for transporting it back to her studio in St Ives and to cover a living wage while repairs were undertaken. Secondly, and more importantly, that the gallery would commit to buying work to the sum of an agreed amount every year. This would secure Hepworth a minimum annual income, and in her words, ‘enable me … to assess my production expenses a little better at this end and feel happier about paying all the transport’.25 Generating income clearly played heavily on Hepworth’s mind and in response to this request Peter replied, ‘in view of our financial position, we cannot commit ourselves to any purchases. However should our financial position continue to improve, we should like to make some outright purchases, and will indeed, try to do so this year … It is possible that, without committing ourselves, we may be able to fulfil such a sum in any case’.26 While Hepworth was satisfied, at least initially, with this stated intention, the matter of a fixed income remained a pressing concern and she revised her contract with Gimpel Fils in 1957, 1960 and again in 1962 in an attempt to secure this financial commitment.

Having established the terms of their working relationship in January 1955, Hepworth and Gimpel Fils scheduled the artist’s first solo exhibition at the gallery for June 1956. This was a prestigious slot in the art world calendar, and one she occupied for all five of her solo exhibitions at the gallery, in 1956, 1958, 1961, 1964 and 1966.27 In June, London’s auction houses Sotheby’s and Christie’s held their fine art sales, which brought international clients to the city. Scheduling her exhibitions in the June slot ensured that her work would be exposed to a larger number of collectors and curators and maximise the potential for sales.

Charles and Peter both visited Hepworth at her home in St Ives during the early months of 1955 and she visited the gallery when she travelled up to London to oversee her set and costume designs for Michael Tippett’s opera, The Midsummer Marriage, which opened at the Royal Opera House on 27 January 1955.28 Although it had been Charles who first met with Hepworth, it was Peter who became Hepworth’s main contact regarding business matters, while Kay quickly became the source and recipient of gossipy letters.29 Indeed, the bond between Hepworth and Kay was strong from their first meeting. On 30 January Hepworth wrote to Kay:

Thank you for the really lovely dinner party on Friday evening – it made such an unexpectedly happy ending to my time in London, +, in addition, a wonderful beginning, more auspicious than you knew though I think you guessed. I felt I had met a new friend – that you were looking through me + I like it that way.30

Over the course of their professional lives Kay and Hepworth confided in one another, and on the publication of A.M. Hammacher’s book on the artist in 1968, it was to Kay that Hepworth dedicated the gallery’s copy. Members of staff at Gimpel Fils have recalled that in the 1990s Kay continued to speak of ‘Barbara’ with such regularity that it was possible to forget that she had died some twenty years earlier.31

Fig.2

Charles Gimpel

Photograph of Barbara Hepworth, October 1955

© Estate of Charles Gimpel

Courtesy Gimpel Fils, London

For Charles and Kay, business trips to St Ives quickly became social occasions. In October 1955 Charles, a self-taught photographer, took a series of portraits of Hepworth at her studio (fig.2). On 29 October Hepworth wrote, ‘Dearest Charles, I think the photos you took of me on the roof are most amusing: they are alive and informal … But please do destroy the ones taken outside my studio door. Your photography is fine. My face is difficult’.32 Charles’s photographs, and Hepworth’s response to them, perhaps show her as Bryan Robertson was later to describe: ‘her studio and her garden were her domain, and there she was a friendly and warm spirited, but shrewd, hard working and practical Yorkshire woman’.33 These characteristics are also evident when, in February 1957 while Charles and Kay were visiting St Ives, she wrote to Peter in London to enquire about the progression of sales.34

While it should be expected that correspondence between an artist and their dealer would concentrate on sales and exhibitions, the letters between Hepworth and Gimpel Fils also show that Hepworth felt a personal debt to the Gimpel family, who offered her friendship as well as business and financial support. Hepworth’s relationship with and dedication to the Gimpel family was expressed regularly and forcefully, and was undoubtedly deeply felt. When, for example, in September 1956 she signed a contract with the Martha Jackson Gallery without first discussing the particulars with Gimpel Fils, she later reflected to Charles, ‘I was not right to sign any form of contract without consulting you + I am simply prostrated to-day over it because Gimpel Fils, + you and Peter mean so much to me + I am so devoted to you all, that I really can’t bear it’.35 During this time the gallery also supported her and her family in other ways; Gimpel Fils negotiated the sale of early work by Henry Moore belonging to Hepworth’s parents, and in January 1958 the gallery acted as a mediator between Hepworth and Nicholson, buying her half-share of a painting by Piet Mondrian that she owned jointly with her ex-husband (fig.3).36

Fig.3

Charles Gimpel

Photograph of Barbara Hepworth at home c.1957–8

© Estate of Charles Gimpel

Courtesy Gimpel Fils, London

Despite the warm friendship and the regular sale of works, the issue of an annual income continued to concern Hepworth and she again raised the question of a regular stipend from the gallery in a letter to Peter dated 1 January 1957. In her letter Hepworth relayed that Charles had apparently told Nicholson that the Gimpels had come to a decision ‘as to the amount per annum which you feel you can invest + upon which I can rely’.37 Nothing was agreed at that time and the matter was raised again in May that year when Kay wrote to Hepworth outlining a proposal that would guarantee Hepworth £600 per annum. The Gimpels suggested that they would guarantee sales of £600, whereby ‘if your percentage from the sales do not attain this amount, the gallery would make it up to you by outright purchase’.38 However, Hepworth replied stating ‘what I had in mind was that the Gallery should give me the same arrangements that they gave Ben – i.e. that they contract to buy work of mine to the value of £600 a year, this amount of work to be sold to the Gallery at half price’.39 Presumably Hepworth’s expectation was that the guaranteed stipend would be in addition to the annual sales made by the gallery. Discussions rumbled on and in August 1957 she wrote to Gimpel Fils stating that she wanted to revise the terms of her contract, which was indeed re-negotiated prior to her second solo exhibition at the gallery in June 1958.

By 1956 Hepworth had found the confidence to engage with bronze in a more sustained way than hitherto in her career, and Gimpel Fils quickly established a pattern of ordering and selling these bronze editions. In addition to these sales, as per the terms of her original agreement, Hepworth continued to make private sales direct from her studio throughout the late 1950s. However, although casting bronze multiples allowed for greater financial returns, Hepworth became increasingly concerned about the chain of supply and demand. In 1960 she again re-negotiated the terms of her contract, stating:

All my life I have kept the necessary amount of freedom which I need for good work – and I know you will be the first to appreciate the importance of this. I am absolutely loyal to Gimpel Fils and love you all dearly – but I must have the freedom which enables me to experiment and to do my best work. Producing and selling more and more and more is not the way for me … I want to … live at the tempo which suits my creative faculties and not be driven to become a factory.40

Hepworth’s concerns about mass producing bronze casts stemmed not only from a desire for quality control, but from the complications of having to manage an increasing number of requests from Gimpel Fils for new sculptures to replenish sold stock. In the early 1960s Hepworth chastised Kay for pre-selling examples of sculptures that Gimpel Fils did not have in London. In addition, the expenses involved in bronze casting clearly weighed heavily on Hepworth’s mind. Despite having requested the same contractual terms as Nicholson in 1957, by September 1961 she stated: ‘I don’t think there is any similarity between contracts with painters and contracts with sculptors. I cannot think of any circumstances under which a painter can go bankrupt on his overhead expenses nor are there any circumstances in which a painter can be inhibited by lack of money’.41 A new contract signed in 1962 gave Hepworth greater freedom to work with a range of commercial galleries both in the UK and internationally and she stated that these negotiations were driven by an attempt to ‘stabilise my financial resources’.42

In 1988 the curator Penelope Curtis noted that much of Hepworth’s energies in the 1950s had been spent ‘urging her gallery to push her work more proactively’ and that ‘she eventually changed Gimpels, her long-time supporters, in favour of Marlborough Gallery’.43 While this characterisation of Hepworth is fair, it is perhaps more applicable to the 1960s, after she became frustrated with Gimpels Fils following what the artist termed ‘the disaster of Documenta’ in 1959.44 As Curtis outlined, Hepworth blamed Gimpel Fils for allowing three small works to be exhibited at the major international art exhibition in Germany, rather than a selection of larger, more important sculptures, and in a letter to Charles wrote that ‘it will take me years to live this down’.45 Although Peter protested that the selection had in fact been made by the Documenta committee, which ‘chose the easy way by not visiting you (although we asked them to do so) and picking the small sculpture that they saw in the gallery’, Hepworth nonetheless felt that this poorly conceived presentation was detrimental to her international reputation, and held Gimpel Fils entirely accountable.46 In his response, Peter felt it necessary to puncture Hepworth’s overinflated perception of her status within the art world and to highlight her tendency to refuse responsibility for her own decisions: ‘In a way … the work chosen by the Documenta committee indicated the true standing that you had with them at the time … You did not at the time say that unless they took a larger sculpture, you would prefer not to be represented. It is only now looking back that you feel that we should have refused to send.’47

While Hepworth was exacting and prone to stubbornness, Charles’s and Peter’s personalities and interests also had an impact on what the gallery could achieve. In 1960 the brothers were described in the Sunday Times as ‘pleasantly disillusioned about art dealing’, and both pursued personal interests beyond the business.48 Between 1958 and 1968 Charles Gimpel made six trips to the Arctic Circle with the Scott Polar Institute in order to carry out his own photographic projects documenting the lives of the Canadian Inuits, and collecting examples of their work.49 With Charles away for months at a time, Peter and Kay were left overseeing all gallery business and with just four members of staff – the Gimpels and a secretary – the gallery’s activities were often over-stretched. However, despite their limited resources, Gimpel Fils was an ambitious gallery, if not as ruthlessly business-minded as Hepworth wished. The 1960s saw the expansion of not only its stable of represented artists, but also the establishment of two new galleries: Gimpel & Hanover in Zurich, a joint venture with London’s Hanover Gallery which opened in 1963, and Gimpel & Weitzenhoffer, New York, which opened in 1969, managed by the young dealer Max Weitzenhoffer. Although Hepworth exhibited in both of these international venues, temporarily placating her desire to exhibit abroad on a more regular basis, her ambitions were ultimately greater than Gimpel Fils could accommodate.50

Hepworth had three solo exhibitions at Gimpel Fils during the 1960s – in 1961, 1964, and the last in 1966, although she did not formally sever ties until 1972. During her final eight years with the gallery her relationship with the Gimpel brothers became increasingly precarious; while declaring absolute loyalty to the gallery she also limited the number and availability of her sculptures. During this time she established an advisory committee made up of friends, her solicitor and her financial advisor to guide her decision making, and also entered into a business relationship with the commercial gallery Marlborough Fine Art in London. Under these circumstances trust between Gimpel Fils and Hepworth began to break down, and in July 1964 Hepworth reproached Charles for treating her ‘like a naughty schoolgirl’, and Peter was called upon to smooth the relationship.51 The following month Hepworth thanked him ‘for speaking so kindly on the telephone’, but went on to state that ‘Charles’s emotional reaction (which I understand of course) did not alter my intelligent assessment of events’.52 Although Hepworth had been pleased with efforts made by the Gimpels to ensure that her exhibition of June 1964 had been a success, this was nonetheless a fractious period in their relationship. She wrote to Peter:

I think I have had a gorgeous success with my show and I am deeply appreciative. I am also loyal to you – though I cannot identify myself with your personal dislikes. Nor would I like to think that if you began to like me less (because I write to you candidly) that you would not feel able to sell my work so easily. This really would shake me up!53

The cause of Charles’s outburst and the waning of Peter’s regard for Hepworth – if not her work – was her proposal that she work closely with Marlborough Fine Art and its New York outpost Marlborough-Gerson. As the art historian Emma Roberts has documented, throughout the 1960s Hepworth became increasingly obsessed with having international commercial representation, particularly in the United States and Germany, which Marlborough was able to offer.54 At this time Marlborough had contracts with Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland and Francis Bacon; Nicholson also worked with Marlborough at this time and joined them exclusively in 1967.55 That Marlborough worked with these artists was appealing to Hepworth, who felt that exhibiting alongside artists of her own generation was crucial to ensuring her position within narratives of British – and international – modernism. These concerns, together with overtures from Marlborough and her frustrations with Gimpel Fils’s apparent lack of assertiveness came to a head with her exclusion from the third Documenta in the summer of 1964.

Although she wrote to Peter that ‘the unhappy events of 1959 should be left right out of our discussions’, Hepworth’s fury at her omission from Documenta in 1964 was surely coloured by her disappointment with the 1959 exhibition.56 She regarded her exclusion from the third Documenta as an avoidable repetition, made all the more frustrating given that she had written to Peter in March 1964 suggesting he propose a display of four large-scale sculptures to the selectors.57 Her sense of injustice must have been exacerbated by the fact that both Moore and Nicholson were included in the exhibition to great success. She wrote to Charles, ‘of my age group and reputation, I was pretty well the only one left out’.58

That Moore and Nicholson both worked with Marlborough had not gone unnoticed by Hepworth and it was probably around this time in 1964 that she was informed by her friend the critic Herbert Read that Harry Fischer of Marlborough was keen to work with her, although Fischer was apparently reticent about making the approach for fear of offending the Gimpels.59 Since re-negotiating her contract Hepworth was free to work with other commercial galleries and given that Marlborough had outposts in the USA, Germany and Italy, they were undoubtedly an attractive proposition for advancing her international reputation. Although Marlborough was not initially named outright in correspondence between Hepworth and Gimpel Fils, the gallery was almost certainly identified as a possible business partner in Hepworth’s telephone conversations with the Gimpels. On the subject of exhibiting internationally, she wrote to Peter that,

As regards Gallery X, I do assure you that there has not been anything improper – very far from it. Also there is absolutely no question of disloyalty on either my part, or on the part of anybody else. It was entirely my idea as to achieving a practical solution … the Gallery I proposed already buys and sells my work on the market and I have noticed that very great rise in price of H.M’s [Henry Moore’s] work and B.N’s [Ben Nicholson’s] and having a somewhat native Yorkshire shrewdness I recognise success and efficiency.60

Gimpel Fils was opposed to Hepworth working with Marlborough and their position was deeply felt. In July 1964 Charles informed Hepworth that the gallery regarded Marlborough as having ‘the worst reputation in the art world that has yet been enjoyed by any gallery in the last three generations of our profession’.61 Later that year Hepworth wrote to Peter stating, ‘ever since you said that “you would rather close G.F. than work with the M. Gallery in any capacity” I have been heading for a nervous breakdown’.62 At this time Hepworth was already collaborating with Marlborough on a large-scale historical show, Art in Britain 1930–40, scheduled for March 1965.63 Hepworth complained to Peter that in not working with Marlborough he was in effect separating her from her contemporaries and justified her participation in the show stating, ‘surely to maintain the historical position and the price level and my own creative faculties, you should not isolate me from my age group’.64 Peter responded stating that the Gimpels’ disinclination to work with Marlborough was based ‘purely on a wish to protect our reputation’.65

Nonetheless, in February 1965 Hepworth signed a contract with Marlborough in which it was agreed that the gallery would promote her work in Europe and America.66 A month later Art in Britain 1930–40 opened in London, and while ostensibly a group exhibition, Hepworth’s sculptures were presented together in their own room, and would certainly have been regarded as an introduction to the type of support and presentation that Marlborough could offer. As Roberts has shown, between 1965 and 1972 Hepworth was subject to increasingly aggressive, even manipulative pressure from Fischer and Frank Lloyd of Marlborough-Gerson, who wanted her to sign an exclusive contract with their galleries.67 However, it should be noted that during this time Hepworth also courted Marlborough’s attentions, even when, in 1969, Naum Gabo initiated legal proceedings against Marlborough-Gerson and she was aware of the gallery’s more unscrupulous activities.68 In May 1971 Hepworth wrote to Harry Fischer and proposed that Marlborough exhibit her new multi-part work Family of Man 1970.69 This proposal precipitated contractual negotiations between Hepworth and Marlborough and on 3 February 1972 Hepworth wrote to Peter Gimpel:

I have to write a very difficult letter to you as I must tell you that I have agreed to make exclusive agency arrangements with Marlborough.

I find it very painful as I count the three of you among my close friends, but there is only one gallery in London who can show my big new group, in addition to which they have a world coverage which is, I think, unique. When I entered into discussions with them about showing the Nine Figures they insisted that my arrangements with them should be exclusive. It has taken me a long while to make up my mind about this and I have only done so after great thought and taking advice. Although I have now made up my mind, on personal grounds I am extremely sad about it. There is not very much more that I can say except that I am afraid that I shall have to ask you to release all my unsold work which you hold in due course.

I have made the point that possibly Marlborough would eventually be prepared to make some arrangements with you so that you would be able to continue to hold some of my work for sale. They are sympathetic about this, though they say that for an initial period they feel it essential that no other gallery should have my work and I understand this. When this initial period comes to an end, as I am sure it will, I will be in touch with you again. I am hoping very much that although I know you will be upset at my decision you will not feel that it has brought our friendship, which I value so much, to an end.70

It is arguable that, since Hepworth had had a solo exhibition at Marborough in 1970, her letter should not have been unexpected to Gimpel Fils. However, Peter, Charles and Kay felt Hepworth’s departure as a great betrayal, both professionally and personally.71 Prior to receiving her letter, Peter had been concerned that Hepworth’s reticence at sending new work on consignment was because she was slowing her rate of production due to ill health.72 Her reasoning that Marlborough was a larger gallery and could therefore accommodate her new bronze sculptures would have had a hollow ring. Charles had organised two exhibitions of large-scale outdoor sculpture in August 1968 and September 1970 at Syon Park, London, in order to showcase works by Hepworth, and other leading sculptors that the gallery space could not physically accommodate; the 1970 exhibition, which remained in situ until 1972, included her enormous Three Obliques (Walk In) 1968–9 (fig.4).73 In addition to which, in late 1971 Gimpel Fils was preparing to move to larger premises on Davies Street, and was established in that new space in August 1972. Hepworth not only knew of the move, but had spoken to Kay Gimpel in November 1971 about showing Family of Man in the space. In a memo, Kay recorded that Hepworth ‘was “passionately interested” in our project for a show of the 9 figures, her heart was entirely in favour of it’.74 It must have been devastating for the Gimpels to realise that Hepworth had already been in discussions with Marlborough to show the multi-part sculpture when she made these impassioned claims. Ultimately, according to the gallery’s subsequent director, René Gimpel (Charles’s and Kay’s son), Hepworth’s reasons for leaving Gimpel Fils were financial; he recalled that according to his parents, Hepworth left Gimpel Fils because Marlborough had apparently agreed to subsidise her casting costs and put her on a substantial retainer.75 Although the details of Hepworth’s contract with Marlborough have not been verified, it was nonetheless ‘exclusive and with a substantial advance to the artist’.76 To the Gimpels, it was galling that Hepworth not only prioritised finance over friendship, but had chosen to work with a gallery that they regarded as so completely unreputable.

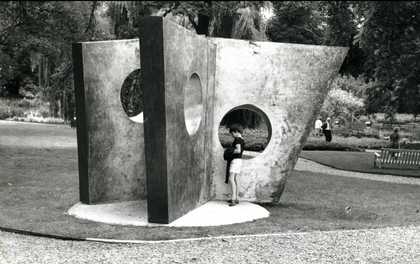

Fig.4

Charles Gimpel

Installation view of Barbara Hepworth’s Three Obliques (Walk In) 1968–9 at Syon Park, London, 1972

© Estate of Charles Gimpel

Courtesy Gimpel Fils, London

Needless to say the business relationship, and consequently the friendship, ended badly. Hepworth instructed Peter to deal with her solicitor Anthony Lousada on all outstanding financial affairs, and although there was an initial attempt to be amicable, by 22 March Peter was prompted to write ‘the soon[er] we are free of all relations with Barbara Hepworth the better’.77 At the time Hepworth left the gallery she was owed £4,483, which was paid by 31 May 1972. However, correspondence over financial affairs continued until September, leading Peter to write to Lousada, ‘I remind you that in the last three years with us, the artist earned from our sales over £230,000’.78 That Peter could not bring himself to refer to Hepworth by name perhaps reveals how deeply he was hurt by her departure, but his statement is noteworthy on another count; the sales mentioned were made in a period during which Hepworth did not have any solo exhibitions at the gallery, demonstrating that backroom sales – made outside of the exhibition – were healthy, even during a period when she was limiting the number of sculptures available to Gimpel Fils. In a final act of defiance, the Gimpels infuriated Hepworth by holding an unauthorised exhibition of her work in October 1972 – the second show in their new Davies Street space. (It is probable that this was the exhibition slot originally intended for Hepworth’s Family of Man.) On learning about the show Hepworth wrote to Gilbert Lloyd of Marlborough, reporting, ‘I have had a beastly week over the shocking surprise of the exhibition at GF; but I was even more depressed yesterday by the photograph in the TIMES which I suspect may be a GF snapshot enlarged, from about two years ago … It is childish of me to show anger, but … the “misprint” of the exhibition being of new work, did hurt me’.79

In 1955 when Gimpel Fils became Hepworth’s agents ‘with enthusiasm, and on the friendliest of terms’, neither party anticipated the how close they were to become in such a short period of time.80 The friendship, coupled with the intellectual and financial support provided by Charles, Kay and Peter coincided with, and undoubtedly contributed to Hepworth’s renewed energy and focus in the mid-1950s. Yet although Hepworth clearly recognised the importance of the commercial art world and sought to utilise it to ensure her financial security and the furtherance of her artistic reputation, she was never entirely able to fully entrust the promotion of her work to others. Her attention to the contractual details of her relationship with Gimpel Fils and frequent re-negotiation of their respective financial commitments demonstrates that the agency of the artist was in no way subsumed within this particular artist-dealer relationship. Although she appreciated all that the Gimpels did for her, a deep-rooted sense of injustice over her ambivalent critical reputation, her limited international standing, and her desire to ensure her position in future histories of modernism made her amenable to the overtures of other dealers claiming to be able to rectify these long-standing concerns. At the same time, the Gimpels conducted their business in an intellectual and unselfish way, which left them exposed to a breed of commercially driven galleries that increasingly populated the London and international art world in the 1960s and 1970s. Indeed, it is possible to argue that in their dealings with Hepworth, the Gimpels behaved more like patron-agents of the nineteenth century, providing friendship and altruistic support.81 As it turned out, Hepworth decided that in order to achieve her career goals she required a proactive, financially-savvy dealer, whom she found in the figure of Harry Fischer. Hepworth’s departure from Gimpel Fils is demonstrative of the strategic decisions that she had to manage in order to attain the success she believed she deserved. For although Hepworth trusted and valued the friendship of the Gimpels, her ambitions ultimately proved incompatible with what the gallery could provide and it is likely that Hepworth stayed with Gimpel Fils as long as she did because of her friendship with Peter, Charles and Kay. Pulled between personal loyalties and professional aspirations, Hepworth eventually chose to forfeit the personal relationship. With hindsight, the relationship between Hepworth and Gimpel Fils may serve as a cautionary example of the pitfalls of mixing friendship and business.