Personally, I’d rather break my arm falling off a platform than spend an hour in detached contemplation of a Matisse.

Robert Morris 19711

There is a long theoretical tradition reaching across philosophy, political theory and psychoanalysis that valorises play as a means of facilitating uninhibited expression and self-discovery. In Britain, these ideas attained prominence in certain forms of artistic practice in the 1960s and early 1970s, which aimed to initiate new, interactive modes of spectatorship, and have attracted renewed attention in recent years. 2 With participatory forms of art accorded more space than ever in contemporary museums, and as these museums themselves struggle to become more ‘participatory’, it is an apposite time to re-examine the theoretical foundations of the increasingly prevalent – if often unfocused – ideal of the playful museum.3 This paper looks back to three early examples of participatory exhibitions in England from 1965 to 1971, which shared aspirations to activate the viewer, inspiring personal liberation through open-ended and explicitly physical engagement.4 All three were closed early, amid reports of chaos and injury. These are case studies of what shall be termed ‘over-participation’, incidents in which participatory artworks elicited bodily forms of interaction that were deemed to exceed acceptable limits.5 The discussion will centre on a close reading of the now little known exhibition Popa at Moma: Pioneers of Part-Art, held at the Museum of Modern Art Oxford (MOMA) in February 1971.6 Popa at Moma is considered alongside two better known shows – one by the British artists Mark Boyle and Joan Hills at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in 1965 and the other by the American artist Robert Morris at the Tate Gallery in 1971 – as a way of thinking through some of the problems associated with play in the art museum.

The burgeoning field of exhibition studies is rapidly canonising notable exhibitions and their curators as deserving of critical attention and celebration. Studies such as Bruce Altshuler’s Biennials and Beyond: Exhibitions that Made Art History, 1962–2002 (2013) have tended to focus on shows that successfully carried out the intentions of the participating artists and the organisers, and there has also been particular interest in ‘landmark’ exhibitions of the 1950s to the 1970s that were especially influential or original, such as When Attitudes Become Form, held at the Kunsthalle Bern in 1969.7 Far from straightforward successes, the three exhibitions considered here may be deemed failures by most criteria. Yet such events can reveal as much if not more about the artists, institutions and historical periods from which they arose. Moreover, these exhibitions’ claims to radicalise traditional modes of viewing and to instantiate a newly democratic relationship between artist and beholder resonate with many accounts of interactive art today. The art historian Claire Bishop has identified three main claims that have persisted from the 1960s to the present: that interactive art empowers the spectator through the experience of physical involvement; that shared authorship is intrinsically more egalitarian than that of a single artist; and that it promotes community cohesion in an era of social fragmentation.8 These assumptions, especially the first, underpin the histories discussed in this paper. If the promise of freedom held out by these shows could not be kept, what are the implications for understanding play and its relation to structures of power? The colourfully disastrous character of these interactive exhibitions casts new light on the question of success and failure in participatory art practice, and may serve to identify new directions for ludic exhibition-making.

This article makes no attempt to provide a comprehensive survey of the phenomenon of ‘over-participation’, even within this time period or the British context. Instead, the three examples offer an opportunity for contrast and correlation that highlight the unique aspects of each case. In all three, the relations between artists, institution and audience were complex and distinct, irreducible to a single interpretation. By revisiting these exhibitions, however, this paper serves to challenge both the uncritical notion of play as panacea and, conversely, the conventional narrative according to which radical art finds itself inevitably quashed by a repressive institution hostile to the avant-garde. Contemporary reports of these events tended to stress the antagonism between museum, public and artist, but as shall be seen, this simplified the historical situation at the expense of a more intricate assessment of the delineations of power.

O What a Lovely Whore, 1965

Invited by assistant director Jasia Reichardt to organise a series of happenings at the ICA, Mark Boyle and Joan Hills staged their first event on 11 May 1965.9 Titled O What a Lovely Whore, which offered a comic twist on the name of the 1963 stage musical Oh What a Lovely War!, the happening served to articulate the artists’ critique of the conventional relationship between a theatrical play and its audience, whose silent reception of a production they likened to the subjugated passivity of a prostitute.10 By designing the event to be boldly open-ended, Boyle and Hills aimed to reverse the dominance of artist over audience and catalyse a more active response from spectators.11 According to the instructions subsequently produced by the artists, the crucial components were as follows:

- Prepare a wide range of activities with maximum participation incentive.

- Light them with two or three (i.e. 1 not enough) spotlights on stands with wheels, so that the audience can control them.

- When all the audience start to arrive hold them in a screened off area until they have all gathered.

- Announce that you’re not going to do any event and if they want an event, they’ll have to do it themselves.

- Open screens or curtains.12

According to Boyle, he would have been content if the audience had responded to his prompt with inaction, but the outcome exceeded all expectations.13 One contemporary description in particular is worth quoting at length:

The audience moved in and went berserk: they worked projectors and tape recorders, performed on numerous plastic instruments, painted by numbers, smashed a piano, took scripts from actors, acted with them or directed the performance, danced with ballet dancers, edited films and projected them onto walls, ceiling and people, directed a film of the proceedings, controlled the lighting, jumped on trampolines, prepared a press communiqué. They decided to build a new type of piano out of the pieces of the old. It began to be the centre of the event. It was smashed and re-smashed, built and rebuilt as the piece developed a rhythm of its own and some hours later stopped suddenly with the gallery ankle deep in debris.14

In his description of the event published in 1978 Boyle described a ‘huge throng clamouring in the street outside to get in’, while ‘everything was getting smashed’. His anecdotes include the arrival of the police (‘I turned and saw it with their eyes. It was like a riot. I got them each a stiff drink and escorted them out of the ICA making jokes about modern art’) and the ‘thumping’ of the gallery manager.15 Boyle’s friend, Nicholas Irving, had his leg broken while playing the piano during its destruction, and his musical compositions were set on fire. Boyle’s account of the game that emerged is as follows.

A curious ritual began to develop … it was as though they had communally decided that having built a new type of piano, they needed to find a new way of playing it. The sculpture/piano was at one end of the gallery. At the other end, they sat a man on a chair on a trolley. He held a long pole, like a lance. The trolley was about 3 feet height. Everyone else formed into a corridor between the trolley and the ‘piano’. They were all clapping and stamping rhythmically. Then about ten people would get behind the trolley, some of them holding the chair on, and it would be driven at great speed towards the ‘piano’. When the man hit the ‘piano’ with the pole he would go up in the air and crash among the audience and the pile of piano debris would collapse to the floor.16

Fig.1

Mark Boyle and Joan Hills

O What a Lovely Whore 1965 (film still)

16 mm film, black and white, sound

4 min 27 sec

Courtesy Boyle Family

© Boyle Family

However hyperbolic these descriptions may seem, archival recordings made of the event confirm many of the details. The artists provided a movie camera to be used by participants, who documented the destruction and precarious reconstruction of the piano in vivid if haphazard style (fig.1). The tape recording, too, testifies to an atmosphere of hedonistic chaos amid the sounds of sawing, banging, howling, stamping, and a woman claiming that it had all gone ‘bloody wild’.17 According to Boyle a member of the ICA committee eventually intervened, shouting ‘“This is a gallery”. It stopped immediately … we repainted the gallery and rehung the paintings of the current exhibition’.18 The following issue of the ICA Bulletin announced that ‘owing to the overwhelming success of the Event … it has been decided to postpone the next one until larger and more suitable premises are found’.19

Robert Morris, 1971

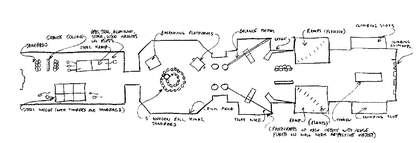

While Boyle and Hills sought to galvanise their audience into action with strategic darkness, alcoholic drinks and props such as a trampoline, an orchestra, balloons, and a DIY film cutting and projection station, the American artist Robert Morris had very different intentions for his 1971 exhibition at the Tate Gallery.20 Morris had created a large new installation to be the centrepiece of his ‘retrospective’, filling the Duveen Galleries with a series of objects and structures that derived formally from his minimalist sculpture but were, for the first time, designed for physical engagement. The galleries were divided into three sections, each filled with works designed for a certain kind of encounter; visitors moved progressively from acting upon large objects, mostly constructed of wood and metal, to confronting fixed structures such as ramps, tunnels and tightropes which prompted certain precise responses from the body (fig.2). The works were simply constructed out of cheap, industrial materials over a short period of time, and were intended as temporary structures to be recycled after the exhibition’s closure.21 As Morris put it in a letter to the exhibition’s organiser, Michael Compton, ‘the show is more environmental than object-like, offers more the possibility – or even necessity – of physically moving over, in, around, rather than detached viewing. Personally, I’d rather break my arm falling off a platform than spend an hour in detached contemplation of a Matisse’.22

Fig.2

Robert Morris

Plan for Tate Gallery exhibition 1971

Tate

Morris may have joked to Compton about broken bones, but he intended the exhibition to incite a sedate, even ‘ruminative’ form of visitor play.23 Days before the opening Morris made a short 16 mm film of the installation featuring three visitors, a nude woman and two clothed men, whose slow, meditative actions present the exhibition as an idealised arena of quiet phenomenological self-discovery.24 When the exhibition opened to the public, however, the atmosphere was quite different. ‘Sorry, Bob, you misjudged us’, crowed the critic Reyner Banham in the New York Times, who was moved to particularly exuberant prose in describing the experience of the press preview to his American audience:

the most resoundingly successful disaster I have ever attended … intoxicating, irresistible, completely deafening and fabulous; by the end of the private viewing the place was a bedlam in which all rules of decorum had been abandoned as liberated aesthetes leaped and teetered and heaved and clambered and shouted and joined hands with total strangers.25

The exhibition was compared by critics to an ‘Army assault course’, an ‘adventure playground’, and in the words of Time Out, ‘a gymnasium, only simpler’.26 More sympathetically, the ICA’s Reichardt noted to the presenter Melvyn Bragg on BBC radio that the show was remarkable for its context if not for its content, noting that while ‘participation is not new … it is the only time I have ever been to the Tate Gallery when one could touch everything, not only touch but walk on it’.27 Morris had distinguished his ideal of adult participation from a child’s engagement (‘time to press up against things, squeeze around, crawl over – not so much out of a childish naiveté to return to the playground, but more to acknowledge that the work begins to exist at the limits of our skin’28 ), but these subtleties were evidently lost on the visiting public, many of whom perceived in his exhibition an invitation to collective regress.29 In the face of what Compton described politely as ‘exceptionally exuberant or energetic participation’ and the Daily Express more salaciously termed a ‘five-day orgy of destruction’, after multiple injuries and the disintegration of the participatory structures, Tate closed the exhibition.30

Popa at Moma: Pioneers of Part-Art, 1971

Only two months prior to Morris’s show at the Tate, Popa at Moma: Pioneers of Part-Art had opened and closed in a single evening at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford.31 Although Popa at Moma, like Morris’s exhibition, had received wide publicity ‘because of the appetite of reporters for stories of disaster’, only one publication noted the similarities, perhaps because newspaper reporters rather than art critics covered the closures.32

MOMA was a much younger organisation than either the Tate or the ICA, having opened only in late 1966. Its founder, Oxford architect Trevor Green, intended it to house England’s first modern art collection, but it quickly evolved into an alternative space rather than a museum proper. It was daringly housed in a reclaimed brewery building in a ‘dismal, depopulated street’, and became known for experimental exhibitions of environments and kinetics by young artists and collectives such as Stephen Willats, the Archigram group, and Eventstructure Research Group.33 Kenneth Garlick of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, writing in a confidential report to the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB) in 1969, described MOMA as ‘rather way-out … [but] well patronised by undergraduates’.34 In the summer of 1970 Peter Ibsen, a young South African trained in painting at Chelsea School of Art, was appointed as the new director straight from his Courtauld Institute MA, joining the museum in a year in which it received a small ACGB subsidy of £5,000.35 Apart from a secretary, there were no other staff at the museum, and the Council of Management took an active role in decisions.

Popa at Moma was unusual in having been conceived and organised by undergraduate members of the Oxford University Art Club (OUAC). Rupert Legge and Mark Powell-Jones applied to the ACGB in early 1970 for a one-off grant of £120.36 Their proposal, originally entitled Art of the Id, made ambitious claims for a new genre of art, which could uniquely stimulate

the direct interplay of ideas between the artist and the observer, culminating in a spontaneous burst of energy, a desire to respond and give back directly to the work. Up till now this process has been repressed. It is the aim of Id Art to release this response, to free it from the censorship of the Superego. The strict rigours of Museum Code and the one-sided relationship between the artist and Society, have deprived art of a ‘Marcuse’ dimension.37

Legge has since described the proposal as a ‘bogus manifesto of a movement, almost as though it was a movement that exists’.38 When he and Powell-Jones presented the idea to the ACGB in 1970 they were aware of only a few artists working along these lines, but decided ‘in a rather arrogant undergraduate way’ to formalise and promote this interactive tendency by giving it the name ‘Id Art’ (subsequently ‘Part-Art’, short for ‘Participation Art’), and to present the exhibition in the guise of a retrospective in the hope that no contradiction would be forthcoming.39 Duly awarded their £120 on the condition that the exhibition be hosted by MOMA, the two began a process of research to uncover artists working in a suitable vein. While not (yet) describing themselves as ‘part-artists’, a remarkable international group associated with the defunct Signals Gallery in London was discovered by the students discovered and tapped into. Signals was situated on Wigmore Street from November 1964 to October 1966, and was run by critic Guy Brett and artists David Medalla, Marcello Salvadori, Gustav Metzger and Paul Keeler. During its short existence the gallery produced an ambitious news bulletin and a series of important exhibitions that brought together artists such as the Brazilians Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, Li Yuan-Chia from China, and other kinetic artists from Europe and the United States.40 All the artists selected for Popa at Moma – Clark, Oiticica, Yuan-Chia, Medalla, John Dugger and Graham Stevens – had been connected with Signals and continued to associate with each other thereafter. The exhibition was heavily influenced by Brett’s 1968 book Kinetic Art; Brett, who by the late 1960s was art critic for the Times and regularly reviewing MOMA exhibitions, also lent works for the show.41 As Medalla wrote to Ibsen in January 1971, ‘everybody i spoke to in london thinks it’s a coup for moma oxford to stage the first show devoted entirely to part-art’.42

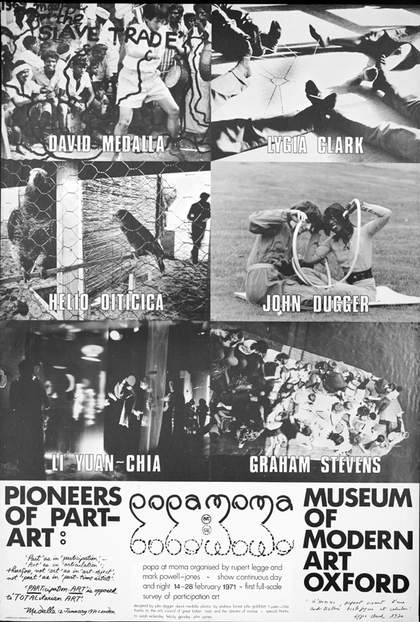

Fig.3

Exhibition poster for Popa at Moma: Pioneers of Part-Art designed by John Dugger and David Medalla 1971

Courtesy Modern Art Oxford

After a chaotic organisation period that required the intervention of Sir John Pope-Hennessy at the Arts Council, an exhibition spanning all three floors of the warehouse building opened for a Saturday evening preview on 13 February 1971.43 The works included touchable installations, large pneumatic structures, and wearable objects such as capes and masks designed to heighten awareness of the human body. Titles such as Discover the Rainbow in Yourself (Medalla) and Canalisation of Psychic Energy (Dugger) recalled the language of New Age spirituality. The press release grandly announced ‘the first full survey of the latest movement in world art’; in lieu of a catalogue, the back of the large poster offered a curatorial statement that reprised the utopian political rhetoric of the ‘Art of the Id’ proposal, promising to remove ‘the barrier around the art object – the barren mystique which sets it in an unalterable mould’.44 Medalla underscored the ethos of emancipation in a handwritten statement printed on the front of the poster, ‘PARTicipation ART is opposed to TOTALitarian ART’, which implied newfound liberation from all conventions of artistic appreciation (fig.3). The local press printed an article on the morning of the opening that quoted Powell-Jones as saying ‘part-art is the most successful at breaking down the museum-age barriers between the observer and the work of art’.45 The exhibition included such germinal works of early participation art as Medalla’s A Stitch in Time, Clark’s Air and Stone, and Oiticica’s Parangolés.46

Fig.4

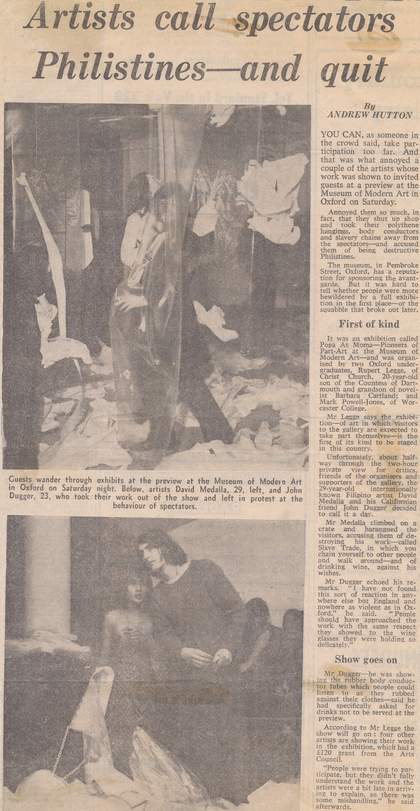

‘Artists Call Spectators Philistines – And Quit’, Oxford Mail, 15 February 1971

Courtesy Oxford Mail/The Oxford Times (Newsquest Oxfordshire)

At the opening the largely undergraduate audience apparently took such statements at their word and, buoyed perhaps by the complimentary wine and the energising effects of bouncing on Graham Stevens’s large inflatables, began to physically engage with works of art in ways unintended by their creators. Medalla and Dugger, who arrived at the exhibition three-quarters of an hour late, were indignant at what they saw. Medalla, a Buddhist, objected to the serving of wine at the preview and, according to the Birmingham Post, ‘told the audience: “You are all Philistines. People should know how to treat works of art.”’47 Although opinions differed as to the degree of real damage done, Dugger told journalists that he had seen visitors beating his works against a wall, adding ‘I have not found this sort of reaction anywhere else but England and nowhere as violent as in Oxford’.48 Medalla and Dugger withdrew their works from the exhibition immediately, while Stevens pulled out the following day. Sensational headlines such as ‘Art Preview Ends in Uproar’ and ‘Artists Call Spectators Philistines – And Quit’ appeared in local and national newspapers, the latter accompanied by a photograph of Medalla dressed only in a sarong, knee-deep in what appears to be a pile of debris. The publicity that the event attracted was completely without precedent in the museum’s short history, as the narrative potency of the events at Popa at Moma proved assimilable to a variety of narratives about the plight of modern culture (fig.4).

The Birmingham Post critic Anthony Everitt, who attended the opening, diagnosed ‘extraordinary goings-on’ in Oxford as a symptom of the tragic alienation between contemporary art and its suspicious public: ‘many of those present saw no connection between what was in front of them and what is generally believed to be art. And they took action accordingly.’49 Another article in the same newspaper (the Birmingham Post published a total of five pieces about the exhibition) illustrated Everitt’s point: ‘Could it not be said that the exhibition fairly sat up and begged for the sort of thing that happened to it? Could it not be that its patrons, confronted with the pseudo solemnities of plastic tubes and polythene bags, sensed that here, at last, was their opportunity to square their account with modern art…?’50 Writing in the Times, Guy Brett, who did not mention his involvement with the conception of the exhibition, defended the intentions of the artists, describing the student crowd as ‘aggressive’.51 A similar tone was taken by the magazine What’s On, which asserted that the visitors ‘treat[ed] their work like the temporary (and inexpensive) decorations provided for one’s amusement at a College Ball’.52 (If the visitors did associate the works with party entertainments it is not entirely surprising: Stevens had produced one of his inflatables for the winter ball at New College, Oxford, in 1969.53 ) The Guardian critic Caroline Tisdall attributed the debacle to the insensitivities of the (male) upper classes, describing the participants as ‘Hooray Henrys’ and accusing Legge and Powell-Jones, both from socially prominent English families, of seeking to ‘promote their own egos as organisers of avant-garde activities’.54 The organisers responded with a letter to her editor, noting that of the six artists only Dugger and Medalla had complained of their art being mistreated and that Dugger characterised the damage to his work as ‘mainly psychological’.55 Another writer blamed the artists for constructing works of insufficient robustness.56 Li Yuan-Chia’s Environment, for example, was largely made of white tissue, coloured paper and hanging discs with poems written on them (fig.5), while the works by Medalla and Stevens were delicately constructed from similarly pliable materials ill-suited for rough use, such as thread, grains, elastic bands, and cloth.

Fig.5

Li Yuan-Chia

Installation view of Environment 1971 at Museum of Modern Art Oxford, 1971

Courtesy Modern Art Oxford

In some cases journalists exaggerated the extent of the mayhem through a lack of understanding of the original works. Graham Stevens’s inflated sculptures were not ‘severely damaged by people jumping on them’, for this was their intended function, but because of technical difficulties with his blowers on the night of the opening.57 Similarly, what may appear to be debris in press photographs of Medalla was in fact the chains and polythene that made up his work Down With the Slave Trade being dismantled by the artist.58 Legge and Dugger have both since downplayed the recklessness of the opening-night visitors, blaming the misunderstanding of a well-meaning crowd in the absence of the artists’ instruction.59 Peter Ibsen’s wife, Antoinette, has even speculated that Medalla planned to withdraw his works from the show to secure maximum publicity.60 Despite differences of interpretation, however, there was an agreement among those present that participation had turned, unmistakeably, into over-participation.

Pure play has no rules

Play and participation are freighted concepts in art theory and may be used to refer to quite different things. In the 1960s and 1970s play was particularly associated with freedoms of expression and, in the gallery, with a departure from reverential encounters with art aligned to formalism in favour of a literal interaction between subject and object or subject and setting. Ludic encounters with art in gallery spaces were often understood to provide a way of resisting not only the traditional model of spectatorship but also what were felt to be the repressive structures of contemporary civilisation. They provided a means of leaving behind not only connoisseurship, but other accepted standards of human conduct as well, allowing the expression of an unfettered authentic self.61 The privileged role of play as an instrument of personal emancipation drew on a motley tradition of progressive thought stretching from the eighteenth-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s promotion of the goodness of human nature to the twentieth-century political theorist Herbert Marcuse’s hugely influential Eros and Civilisation (1955).62 The Dutch historian Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (1938), translated into English in 1949, argued that play was essential to human civilisation; in 1956 it was cited as a key text by the ICA Assistant Director Lawrence Alloway in his catalogue essay for the ground-breaking exhibition This is Tomorrow. For Alloway, the show’s rejection of modernist specialisation in favour of cross-disciplinary practice stimulated ludic creativities in both its makers and the viewing public.63 The psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott’s 1971 book Playing and Reality restated and popularised his longstanding psychotherapeutic belief in the importance of play, broadly defined, to healthy self-realisation.64 1970 saw the publication of Richard Neville’s Play Power, a manifesto for counterculture youth, which mocked the tendency of the left to focus on distributing ‘grubby Marxist leaflets’ about labour rights; Neville and others preferred an individualist ethics of acting ‘like children, narcissistic and guiltless’.65 An idealisation of the child and of nature coalesced with a newfound interest in the creativity of the beholder and a left-wing refusal of economic productivity to produce a broad, if slippery, consensus about the value of play as a form of liberation.

‘PLAY IS FUN. PLAY IS FREEDOM … Pure play has no rules’, proclaimed Neville in typically unequivocal prose.66 His understanding of the ludic as a total absence of restriction figured in the rhetoric of all three exhibitions and their anarchic reception. From Boyle’s and Hills’s DIY ethos, to the celebration of the id with Popa at Moma, to Morris’s declaration that ‘I am really sick of art seen as this kind of situation of masterpieces or precious valuable objects. I just want to change that situation totally’, there seemed to be a politically motivated insistence that the audience could finally take control of works of art, in any manner they pleased.67 O What a Lovely Whore and Robert Morris’s ‘retrospective’ were closed upon the instructions of the galleries’ directors, Dorothy Morland and Norman Reid respectively, and it is tempting to read these as examples of an institution reasserting its disciplinary hold on an unruly audience, papering over the cracks opened by these artists. Art historian Maurice Berger advanced such an interpretation in his analysis of the Tate exhibition, which he described in 1989 as the ‘culmination’ of ‘Morris’s challenge to the repressive hierarchies of the museum’.68 Such confrontations between artists and museums were certainly common during this period: the removal of the French artist Daniel Buren’s work from the Guggenheim International, and the same museum’s censorship of the German artist Hans Haacke’s solo exhibition both attracted wide transatlantic attention in early 1971, while site-specific works of institutional critique were gaining prominence in Europe and America.

The three exhibitions discussed here may have encouraged visitors to contravene norms associated with the gallery setting, but, in contrast to the above examples, it is remarkable how much support the organisers received from their host institutions. Indeed, when Dugger and Medalla turned up late to MOMA and withdrew their works, it was because they found the museum’s attitude too permissive towards its visitors (‘People should know how to treat works of art.’) In an unusual alignment, the ACGB also blamed Ibsen for exercising insufficient disciplinary oversight, noting internally that ‘such exhibitions which invite participation can naturally if not properly controlled … end in something of a shambles’ and deliberated over a revocation of the exhibition’s grant.69 A similar degree of tolerance was displayed by the Tate and the ICA. Michael Compton, who believed that ‘it was part of the function of Tate, while exhibiting this sort of work, to connive in its own subversion’, went to exceptional lengths to keep Morris’s exhibition open, overseeing a number of modifications to the artist’s disintegrating structures to preserve them – and their users – from harm.70 According to notes made by the critic Barbara Reise at the preview, ‘Tim Hilton almost kills other critic’ by deciding to whirl steel weights around his head instead of dragging them along the floor as the artist intended.71 Yet the exhibition remained open five more days despite a stream of minor injuries, closing finally on legal advice.72 Reise explicitly compared Morris’s and Haacke’s exhibitions in a long article for Studio International, but drew a sharp contrast between the Tate’s ‘rational’ actions and the ‘domineering’ attitudes of Guggenheim Director Edward Messer.73 In spite of his installation’s untimely closure, Morris remained on good terms with Tate.

The ICA’s response, meanwhile, may be understood within the context of its own radical history and ideals. Like MOMA in Oxford, the ICA intended to break away from traditional museology, perceiving itself as something closer to an alternative space than a museum or municipal exhibition centre. In the catalogue for its first ever exhibition in 1947, founder Herbert Read described his aspirations to make the Institute an ‘adult play centre’ for the enshrinement of ‘daring experiment’.74 Perhaps accordingly, while the end of O What a Lovely Whore may have been precipitated by a cry of ‘this is a gallery!’, this step was taken only after fire, police, a broken leg and a succession of human catapults had already been allowed to take over the ICA in the presence of Morland, Roland Penrose, and other members of staff. If participation became defined as over-participation, this was not due to hostility from the galleries in question, which made exceptional efforts to accommodate challenging works to a degree that present-day health and safety regulations would no longer allow.

Fig.6

Installation view of the Robert Morris retrospective, Tate Gallery, 1971

Tate

© Robert Morris

In fact, what these three events dramatised was not the playful absence of rules, nor the suppression of institutional critique, but the persistence of spectatorial norms even in their proclaimed absence. The ludic was associated by many of the participating artists with the lifting of ‘museum-age barriers between the observer and the work of art’, but these boundaries shifted rather than disappeared rendered visible in the moment of their transgression. For example, Boyle’s and Hills’s instructions for O What a Lovely Whore were clear about the importance of certain conditions in manipulating responses: ‘The lighting is crucial to the success of the event. There should be a few strong spotlights and that’s all. So that people can begin to do things in obscurity if they want to. Then as other members of the audience are controlling the spots they will suddenly find themselves spot-lit and this heightens their activity.’75 Boyle might have feigned artistic abdication by telling the audience that ‘if they wanted an event they’d have to perform it themselves’, but he and Hills had sown the room with suggestive props, dramatic lighting conditions, and encouraged friends to participate in an attempt to secure the desired outcome.76 For them, the ‘success’ of the event lay in the instigation of a specific atmosphere of frenzied hedonism, a model of participation that was entirely planned if not controlled. Morris had also envisaged a new mode of ideal spectatorship, albeit a very different one to that precipitated by O What a Lovely Whore. For Morris, the ideal, introspective participant was modelled in his film, which was screened in the exhibition, and by the photographs of the objects in use by young Tate staff members mounted on the walls of the gallery (fig.6). His inability to predict the actual outcome of his exhibition renders his film and photographs documents of what the art historian Alex Potts has termed a romantic fantasy.77 In their reviews of the Oxford exhibition, sympathetic critics lamented the absence of a more ‘sensitive’, ‘contemplative’ public, by which they meant one more inclined to attune itself to the artists’ own wishes.78 Brett’s review tried to argue that the artists brought together for Popa at Moma were not ‘tyrannical’, like other artists who organised happenings, but rather encouraged the visitor to ‘listen to himself’.79 While it is true that in the artists’ absence the expectations of how the works were to be used may not have been clearly expressed, the didactic expectations embedded in the idea of ‘listening to oneself’ go unremarked. In expecting an introspective and reverential investigation of their art, Morris, Dugger and Medalla were relying precisely on the conventions of museum reception that their rhetoric forswore. Each of these three exhibitions bore tell-tale signs, material and discursive, that the artists’ practical expectations of ludic behaviour were in some ways narrowly defined, in ways contrary to their ideological models that emphasised freedom and unpredictability. Play, it seems, oversteps certain lines only to redraw others.

Fig.7

Dick Higgins, George Maciunas, Alison Knowles, Benjamin Patterson and Emmett Williams performing Philip Corner’s Piano Activities at the Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik, Wiesbaden, 1962

Courtesy of Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Philip Corner

Photo: Deutsche Presse Agentur

In his letter to Morris after the closure of the installation, Compton speculated on the role played by the institution: ‘The “museum” location evidently did nothing to influence people to a more meditative approach to the objects – a fact which might argue against the view (which I have some sympathy with) that “museums” sterilise works of art.’80 Yet it is not possible to return to an understanding of the Tate, ICA or MOMA as neutral containers with no bearing on the reception of the works of art housed within their walls. Rather than suppressing audience high spirits, the enveloping ethos of these institutions may have actually encouraged them as the temporary lifting of typical prohibitions on touch, noise and movement fuelled a giddy sense of transgression. Such a reading could explain why, according to multiple accounts, adult visitors to Tate behaved far more recklessly than the children who attended.81 Moreover, the social and performative nature of art reception seems to have magnified the excitement as visitors reacted rashly to the novel chaotic atmosphere in the room and (at the Tate) the tremendous noise of the steel pieces. ‘I think people responded a great deal to each other, rather than to the objects’, reflected Compton later. ‘That is, they made up group games, competed, acted out their aggressions, showed off, etc., and this was more likely to happen as the numbers increased.’82 At O What a Lovely Whore the presence of the movie camera passed around participants may also have heightened visitor performances in the dignified Dover Street premises of the ICA. The extremity of the visitor performances in Oxford and London must be understood as profoundly situated. In the case of the ICA, they may also have been influenced by recent art history. While Boyle and Hills did not expect the destruction of the piano in O What a Lovely Whore, it seems likely that this ostensibly spontaneous, iconoclastic gesture was inspired by descriptions of famous Fluxus events, such as Philip Corner’s Piano Activities of 1962 (fig.7).83 For this audience of friends and artists and in the electric, nightclub-cum-gallery atmosphere induced by Boyle and Hills, artistic precedents surely played a greater role in shaping social codes of behaviour than childhood models of play, in which destroying musical instruments would be considered highly inappropriate.

In an article entitled ‘Art and Play-Power: A New Philistinism?’ published in the left-wing English magazine Encounter in the summer of 1971, critic Edward Lucie-Smith connected the recent events at Tate and MOMA by means of a broad critique of ludic and participatory art. With reference to the schism on the issue of leisure that Richard Neville had observed between the ‘new’ and ‘old’ Left, he described the therapeutic agenda of fun-filled play-based culture as serving only to assuage feelings of frustration with the status quo, dissipating the energies needed to achieve political reform. Not only did he view such works as novel manifestations of mass-cultural kitsch, he associated the impulse to participation in art with commercial strategies to secure consumer attention:

In marketing, more particularly in the marketing of convenience foods, what the artist now calls ‘participation’ has long been known, more idiomatically but perhaps more accurately, as ‘add-an-egg’. It has been discovered that the housewife buying a packaged cake-mix feels unconvinced of the quality of the end product because she achieves the desired result too easily. She is therefore instructed to add to the ready-made mix, before she bakes it, one additional, natural ingredient – a shell egg.84

It is not necessary to agree with Lucie-Smith’s conviction that participatory art forms are intrinsically palliative to find something acute in his analysis. Why did some artists believe that it was necessary to engage bodily with an artwork in order to have a critical or creative response to it?85 Playful exhibitions, as has been shown, remained profoundly inflected by normative assumptions, while the ‘detached contemplation of a Matisse’ that Morris rejected could result in an equally intense and personal – even playful – encounter.

For today’s contemporary art audiences, participatory art (or as it may now be termed, ‘social practice’) is no longer inherently surprising or provocative. When Tate Modern partnered with Robert Morris to recreate his 1971 installation in the Turbine Hall in 2009 it attracted 340,000 visitors over two weeks, in contrast to the 1,964 people who saw the original. Yet the mood remained sedate, as its curators had speculated, reflecting the very different historical position of the Tate’s public almost forty years later.86 The ICA’s attempt to restage O What a Lovely Whore as part of their sixtieth anniversary celebrations in 2008 featured an obligatory premeditated piano smashing, a perverse and parodic repetition that shared little of the significance of the original.87 However much nostalgia might be felt for the apparent innocence and spontaneity of the long 1960s, these events are fundamentally singular and unrepeatable, and such recreations run the risk of further obscuring their complexities and peculiarities.

If play is not to be idealised as a lawless sphere of freedom and authenticity, a more nuanced understanding of it needs to be developed, one that acknowledges its social, contextual, rule-bound and performative aspects. Acknowledging the potential for over-participation in ludic artworks is not to suggest the failure of the genre. On the contrary, a more honest assessment of its intrinsic boundaries may help to articulate new resistant possibilities, both within the art gallery and without.