Introduction

During the 1960s and 1970s, Joseph Beuys gradually turned dialogue into a central ingredient of his art, enacting it in his aktionen (‘actions’) and offering it to his audience as a model for change. For instance, he was in Kassel every day for the duration of Documenta 5 (30 June – 8 October 1972), presenting his Organisation for Direct Democracy by Referendum. Nevertheless, Italian art historian Achille Bonito Oliva describes him as a ‘tribeless chief’.1 Oliva was clearly unable to group Beuys together with any kindred spirits, despite the obvious social aspect of his work. Beuys’s art was about interaction, but his motives were his own.

It is therefore relevant to explore the nature of the sociality he materialises in his work. The diversity of Beuys’s output and information available makes it necessary to narrow the focus of this article, which therefore considers his first decade as a performance artist, and especially the period 1966–71, when Danish composer Henning Christiansen regularly made an appearance. It was also during this period that Beuys defined himself – among other things – by means of the notion (or name) of Fluxus.

By the mid-1960s, the landscape of live art, although relatively new, already encompassed anti-art demonstrations as well as events that stayed entirely within the conventions of art; collective as well as individual performances; and performances that took place among the audience as well as those that kept the divide between stage and auditorium. Where to place Beuys, a visual artist interested in creating conceptual connections, and Christiansen, a composer who strived for simplicity, remains a challenging question. In order to set the scene, this article will start by placing Beuys and Christiansen in relation to Fluxus and happenings, broadly speaking the two ’homes’ available for artists who were interested in adding an element of liveness to their work. The sections that follow give a chronological account of the changes that the collaborations between Beuys and Christiansen underwent: ‘Tapes and structures’ deals with the period from 1964 to 1966, during which Christiansen’s work featured in the context of Beuys’s actions but the two only had contact at a distance; ‘Tape recorders and instruments’ deals with the period from 1967 to 1970, during which they often spent time together; and the final section, ‘fluxorum organum and Fluxorgan’, presents the categories of material, process, transgression and interaction in relation to Beuys’s work, as dealt with in Christiansen’s 1968 four-part essay ‘Also a False Interpretation’.2 It is from this essay that the title of the present article, ‘not incorrect and particularly not irrelevant’, is taken. Rather than describing Christiansen as the provider of musical accompaniment to Beuys’s actions or Beuys’s actions as a visual backdrop for Christiansen’s soundscapes, the double negative implied in this phrase is a useful way to understand their work together: neither the one nor the other, but not-not the one or the other.

Fluxus, happenings and actions

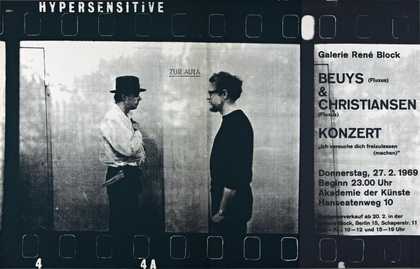

Fig.1

Invitation to I want to set (make) you free (Ich versuche dich freizulassen (machen)) by Joseph Beuys and Henning Christiansen, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, 27 February 1969

Tate/National Galleries of Scotland ARTIST ROOMS AR00864

© DACS 2019

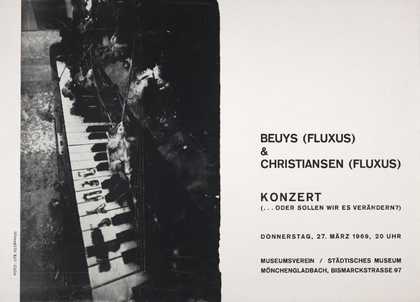

Fig.2

Invitation to ...or should we change it? (...oder sollen wir es verändern?) by Joseph Beuys and Henning Christiansen, Städtisches Museum Mönchengladbach, 27 March 1969

Tate/National Galleries of Scotland ARTIST ROOMS AR00715

© DACS 2019

During these years, the word Fluxus often featured in Beuys’s actions, even though both Beuys and Christiansen had moved away from Fluxus as defined by artist George Maciunas and the circle of people commonly associated with the term. The German Students Party, for example, founded by Beuys in 1967, with Christiansen as one of the co-signatories, was associated with the term ‘Fluxus Zone West’.3 As late as 1969, the names of Beuys and Christiansen were followed by the word ‘Fluxus’ in parenthesis on two invitation cards (figs.1 and 2).

Beuys had a background in visual art and Christiansen was a composer, but both were familiar with the contemporary live art landscape. Broadly speaking, there were two ways open to an artist who wanted to explore the possibilities inherent in live action: Fluxus and happenings. The categories overlap and even an initial survey reveals them both to be amalgams of countless different forms. It is not, therefore, an easy landscape to map onto any artist’s work. Nevertheless, a brief survey of the two provides some insight into the opportunities available for the artists and the implications for their work.

Both Beuys and Christiansen were aware of Fluxus. Christiansen had witnessed a Fluxus concert in Copenhagen in November 1962 and had performed in various locally organised Fluxus events in 1963–4 alongside, amongst others, Arthur Køpcke and Eric Andersen. Beuys had also been aware of Fluxus since the summer of 1962 and had performed some of his earliest actions during a Fluxus festival in Düsseldorf in February 1963.4 The criteria of an event qualifying as ‘Fluxus’, however, remains disputed: according to some, it can only be Fluxus if it was organised by George Maciunas;5 others maintain that particular artists have to have been involved;6 and some consider the attitude of the event to be the most important factor.7 The disparity between such definitions has consequences for the way one understands how these events were organised. During the early years of Fluxus, especially the period 1963–6, George Maciunas, Fluxus’s namer, publisher and impresario, propagated a radical anti-art agenda. Both in his publications and in his organisational work, he modelled Fluxus as anti-art and a campaign for the self-sufficiency of reality.8 Fluxus festivals and objects had to be cheap, mass-producible, accessible to all and performable by all.9 On stage, this led to a performance style characterised by a quick succession of short, almost slapstick pieces. They were not necessarily performed by the artists who had written them and rather presented as a selection from the Fluxus catalogue. On the other hand, Dick Higgins, a co-founder of Fluxus, explained: ‘what held us together was our commitment to an untrendy, unfashionable degree of innovation in the arts’.10 For Higgins, it was about the artists and their work, and the organisational framework and its possible significance was of no real concern.

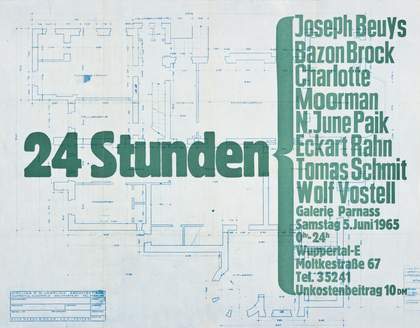

Fig.3

Joseph Beuys

24 Stunden 1965

Tate/National Galleries of Scotland ARTIST ROOMS AR01036

© DACS 2019

Unlike Fluxus, there was no clear organisational aspect to happenings. A happening could be everything from a party or a political demonstration to a collective play or a single work by a single artist. In Germany, the word ‘happening’ quickly became attached to the person of Wolf Vostell, another artist who had worked within the Fluxus context, but had moved into other forms of presentation. Vostell’s work, which he called ‘de-coll/age’, created through destruction, sometimes physically, often by metaphorically tearing away the seductive veneer of capitalist society and exposing the violence underneath. Décollage should here be understood as the opposite of collage, the removal of layers rather than their addition. This is most obvious in his work with torn posters, but Vostell also rubbed out photographs from magazines with various solvents, and smashed or melted toy soldiers and tanks. He was a tireless organiser, involved in many of the iconic performance art events of the mid-1960s such as 24 Stunden, a twenty-four-hour long performance at Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal on 5–6 June 1964 in which Beuys also took part (fig.3). As a platform, 24 Stunden gave a separate room to each participant and a twenty-four hour time frame in which the work could develop. Unlike Maciunas’s Fluxus festivals, the focus was on the single artist and the single work.

Vostell’s own happenings were large events using many performers and lots of props that formed a series of tableaux for the visitors to view. Some were static, but during others, such as 9 Nein Dé-coll/agen at Galerie Parnass and nine locations throughout the city of Wuppertal on 14 September 1963 or In Ulm, um Ulm, um Ulm herum at the Ulmer Theater and twenty-four locations around the city of Ulm on 7 November 1964, the audience was driven from location to location in a bus. Vostell’s characteristic blend of aesthetics and violence manifested itself in 9 Nein Dé-coll/agen when the bus was pelted with light bulbs and sprayed with a hose or when the audience was made to witness a train driving into an old Mercedes.

In this landscape, Beuys takes up a singular position. His actions constitute a category of their own, even when appearing within the context of Fluxus or happenings. Already during the Fluxus festival in Düsseldorf in February 1963, both Beuys and the other participants were aware of the difference. Looking back on the event a decade later, he remembered that Dick Higgins had given him a ‘surprised look’, understanding that Beuys’s contribution was something else entirely.11 According to Beuys, whereas Fluxus was a type of neo-dadaist provocation aimed at criticising the current state of affairs, he himself represented ‘a wider understanding of what Fluxus could be’, one which was also concerned with the creation of ‘conceptual connections’.12 The work in question, Siberian Symphony, First Movement (Sibirische Symphonie, 1. Satz), one of two works Beuys performed in Düsseldorf, is a good example of the nature of his actions and demonstrations. Clearly connected to his sculptural work, it revolved around a grand piano, on the lid of which a clay ‘landscape’ was created and brought to life by attaching it to the heart of a hare by means of a piece of string. It is simultaneously a material action, a call to revitalise a fossilised Western art, a reference to the artist’s own self-mythology – the aeroplane crash in the Crimea during the Second World War and his subsequent rescue by Tartars13 – and an allegory of life, death and resurrection. It has the materialism of Fluxus, the symbolism of certain happenings and a messianic quality – not to mention an aesthetic – entirely its own.

The first event Beuys and Christiansen both took part in, although they did not work together, was the Festival of the New Art (Festival der neuen Kunst) at Aachen Polytechnic on 20 July 1964, subtitled ‘Actions – Agit Pop – De-coll/age Happening – Events – Anti Art – L’Autrisme – Art Total – Refluxus’. It was organised by Tomas Schmit, who had previously acted as Maciunas’s right-hand man. They had recently fallen out, however, over the look of the first issue of the Fluxus magazine V TRE, which Schmit found too ‘jokey’. In his own work of the time, he insisted on small events, preferably amongst the audience, that drew attention to the artificiality of the art setting. The Festival was part of Schmit’s attempt to re-Fluxus Fluxus. As well as a big event in the Auditorium Maximum during the evening, he arranged for small live events to take place during the day on the campus grounds. Beuys only appears to have performed during the evening. His contribution was Kukei/Akopee-no/Brown Cross/Fat Corners/Model Fat Corners (Kukei/Akopee-nein/Braunkreuz/Fettecken/Modellfettecken), another action involving a piano, which this time was altered and revitalised by means of objects that were thrown into it. At the same time, Vostell staged Nie wieder/Never/Jamais, a happening during which the audience could ‘execute’ – or choose not to – a row of performers who dropped down into a heap of yellow powder every time someone blew one of the whistles that had been handed out beforehand.

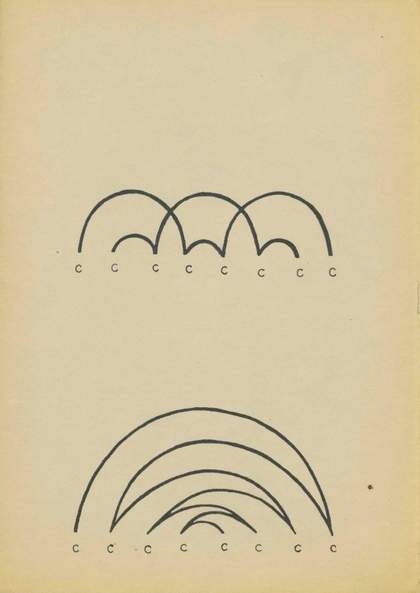

Fig.4

Henning Christiansen

Models (Modeller) Op.33 1968

© Henning Christiansen Archive, Møn

Christiansen sent Schmit a list of works he wanted to perform, but it remains uncertain which were actually realised. Photos of the evening only show the text ‘CLIMB UP’ on one of the walls of the auditorium, the result of one of his Audience Pieces, Op. 19 1964, which simply instructs the performer to write ‘climb up’ on a wall. Christiansen’s work of the time tended towards direct interaction with – and close proximity to – the audience. Not long after the Festival of New Art, however, he shifted his allegiance from Fluxus to the Danish Experimental School of Painting, or ‘Ex-School’. The members of the ‘school’, which at that time was more of an artists’ collective, were primarily painters and sculptors, and their happenings tended to demonstrate problems related to the basics of these art forms: problems relating to concepts such as form, colour and transformation. During the time of his association with the group, which was also the time of his closest involvement with Beuys, Christiansen developed an attitude towards composing that is simultaneously musical and visual. His compositions tended to consist of structures that are as easy to spot on the page as they are to hear during a performance (fig.4). His ‘new simplicity’, as it was dubbed, offers constellations of sound for the listener to hear, rather than for the composer to show off his skill and genius.

Tape and structures

Oliva’s term ‘tribeless chief’ refers to Beuys’s The Chief (Der Chef), performed by Beuys during the May Exhibition in Copenhagen on 30 August 1964 and at Galerie Block in Berlin on 1 December 1964. During the second performance, a tape by Christiansen was played that did not feature in the first. It was the first time that an action by Beuys was accompanied by a soundscape by Christiansen, even if the latter was not present in person. One of the characteristics of tape that attracted Christiansen to the medium, and one that Beuys and he explored more fully during the years that followed, was that sound could be taken from its (acoustic) context and inserted into new ones.14

Beuys did not ask for the tape, Christiansen instead chose to send it unsolicited.15 It contained material from a radio programme by Eric Andersen, broadcast on Danish radio on 17 March 1964, featuring works by Andersen, Christiansen, Køpcke, and George Brecht. Christiansen’s contributions to the radio show were Dialectical Evolution, Op.16 Ib and V, two so-called ‘development pieces’ in which simple instructions generate a soundscape by means of chance or human intervention. In Dialectical Evolution I, Christiansen reads out the numbers one to seven in an apparently random order, first five times, then six and so on progressively. The system is simple, the result complex and ever more difficult to follow. Dialectical Evolution V is an instruction to record sounds that last less than ten seconds at ten second intervals. The result is a composition of strictly structured random sounds.

The tape introduces two themes that play an important role in Christiansen’s work together with Beuys – recording and systems. The use of systems especially links it to The Chief. During the action, Beuys lay wrapped in a roll of felt in the exhibition room for about eight hours, with a dead hare at the top and bottom. Inside the felt roll he had a microphone, through which he made himself heard by means of guttural sounds. In a manner typical of the Beuysian action, materials and actions are used to identify and combine abstract principles; in this case oppositional pairs such as inside/outside, raw material/control and death/resurrection are signified. Christiansen’s works had not been created within this framework, but fit in nevertheless. Both the random noises and regular rhythm of Dialectical Evolution V and the numerical order and randomising system of Dialectical Evolution Ib can be seen in the light of the opposition between raw material and control.

From the autumn of 1966 onwards, contact between Christiansen and Beuys intensified. Christiansen invited Beuys to take part in a festival called Situations (Tilstande) in Copenhagen and Beuys invited Christiansen to participate in the action Manresa at Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf. Christiansen also wrote an article about Beuys in the magazine Hvedekorn.16 This period is the first one during which a thematic and formal dialogue between the two can be said to have taken place. This dialogue was taken to the next level in 1967–9, when Christiansen spent long periods in Düsseldorf.

The article in Hvedekorn, entitled ‘Joseph Beuys and His Energy Plan’ sums up what Christiansen knew about Beuys at the time.17 Combining his own experiences with knowledge he gained from catalogues, he discusses Beuys’s work on the basis of the notions of ‘energy’ and ‘anti-space’ (Gegenraum). Beuys’s work, Christiansen writes, plays itself out between the given and the artificial, between nature and human ‘anti-nature’. Being both natural and artificial, man is capable of intuition, and it is this that enables him/her to create a counter-version of everything: an anti-physics, an anti-chemistry, an anti-music, and so on. These oppositions, part real, part spiritual, create the anti-space where such concepts can thrive. In order to generate them, there exists, or ought to exist a ‘super generator’ of intuitive energy. We may not have found it yet, Christiansen writes, ‘but surely it exists somewhere?’ – a type of rhetoric, and a way to invite others to continue a line of thought, that is very much in the spirit of Beuys.

During Tilstande (Situations), as the two-day event at Galerie 101 in Copenhagen on 14–15 October 1966 ended up being called, Beuys and Christiansen did not perform together, but next to one another. On 14 October, Beuys performed Felt TV (Filz-TV), an early version of a piece that was filmed in 1970 for the filmmaker Gerry Schum’s second TV Exhibition Identifications; and on 15 October he performed Eurasia Siberian Symphony 1963, 32nd Movement (Eurasia) (Eurasia Sibirische Symphonie 1963 32. Satz (Eurasia)). Christiansen’s contributions are listed on the programme as Remarkable (Bemærkelsesværdig), 1-2-3-4-5, Scheme (Skema) and Tank Game (Dunkespil). Not all of these titles can be traced back to his opus list, but eyewitness accounts suggest that a version of his Coffee Pieces was amongst the works he performed. Coffee Pieces is another systematic piece during which coffee is stirred for a specified number of seconds, followed by an equally long silence. At the end, the coffee is distributed amongst the audience, which gives the piece a social element.18

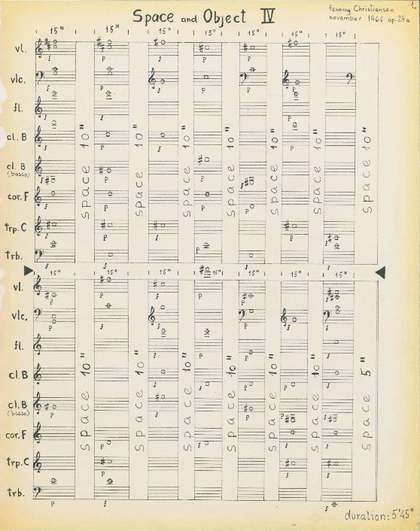

Fig.5

Henning Christiansen

Space and Object IV 1964 (published 1966), from Perceptive Constructions II Op.28

© Henning Christiansen Archive, Møn

The piece is a transitional work. In his first letter to Beuys, sent in October 1964, Christiansen wrote that Fluxus had taught him how to use every possible sound, but that he now faced the problem of form. Should he turn towards ‘psychology’ or ‘architecture’?19 The Coffee Pieces address the person of the performer and the listener, as well as the organisation of the material, and can therefore be seen as both psychological and architectural. Christiansen’s struggle with the choice between the two is even more apparent in a group of compositions from October–November 1964 that he first named Psychological Constructions but later published as Perceptive Constructions (fig.5).20

The work caused quite a stir in Danish music circles. Author Hans-Jørgen Nielsen, a friend of the Ex-School and a collaborator of Christiansen’s, described the pieces as ‘de-dramatised forms’ and ‘forms without an inner center’.21 Whereas music up to this point had been constructed dramatically, Nielsen writes, with complex tensions and points of culmination, these pieces are characterised by anonymity, objectivity and rationality.22 Fluxus had been Christiansen’s farewell to art as the ‘conquest of the world by the artist’, and Perceptive Constructions was his way of creating a new formal alphabet that was no longer ruled by the artist’s ego. This claim, however, was too extreme for the musical establishment to accept. Author Jørgen Pauli Jensen objected that there was no real difference; that Christiansen’s constructions were still subjectively determined and that the listener’s subjective response was still crucial to his/her understanding of them.23 Jazz bass player Finn von Eyben called Christiansen’s compositions ‘arbitrary’, his instrumentation ‘classical’ and his structures ‘banal’.24

What the discussion proves is first and foremost that the word ‘perception’ can be understood in different ways. Nielsen wrote about the structures Christiansen created out of sound and silence; his critics wrote about the listener and the subjectivity of the listening experience. Like the Coffee Pieces, the Perceptive Constructions reveal the composer’s dilemma: architecture or psychology; form or effect? However, they also show that the two are intimately connected – in structure. The pieces make themselves known as simple blocks of sound and silence, connected in simple, easily discernible ways. This brand of simplicity characterises many of the pieces that Christiansen composed during the period of his collaboration with Beuys.

The Coffee Pieces were also among Christiansen’s contributions to Beuys’s Manresa, performed at Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf on 15 December 1966. Beuys wrote: ‘Perhaps you will come and do your coffee drinking/-cups piece in the street simultaneously with my piece?’25 However, it was not Christiansen who Beuys was most keen to include, but another Ex-School member, Bjørn Nørgaard. Nørgaard, 19 years old, who had recently started out as a sculptor, performed a series of ‘material actions’ (Nørgaard’s own term) during Tilstande that was entirely in the spirit of the Ex-School, and Beuys seems to have taken to them immediately:

Could you find out for me whether it is possible to have the boy who did the piece with the feet at Kongensgate … ? Conditions are

1. He has to repeat the same thing as in Kongensgate

2. He has to wear the same clothes as in Kongensgate same shoes etc.

3. He has to bring the same tape fragment that was played very loudly during the first evening.26

The tape appears to have been particularly important to Beuys.27 He mentioned it in two more letters, stressing its rhythmic quality. Nørgaard’s actions that the tape accompanied also had a kind of rhythm to them. Their general description is ‘a random number of randomly picked materials are worked with and brought in relation to my own legs’.28 He used his feet to perform actions like crushing light bulbs and a clay cube, or covering a plank with liquid soap, and ended the performance by casting them in plaster, each foot in its own cardboard box.

Nørgaard’s invitation to perform in Manresa was very different from Christiansen’s: the former had to replicate a previous performance exactly, while the latter was given the choice. On the other hand, Christiansen is not even mentioned in the invitation, which only states ‘Beuys 20° MANRESA mit Bjørn Nørgaard’.29 What Christiansen ended up loading into his car was a representative cross-section of his production during the preceding two years, including both works known to Beuys and new ones: the entire Perceptive Constructions; Dialectical Evolution 1b (also on the tape that Beuys had used already); a piece from To Play To-Day, Op. 25; Knocking; a poem by Hans-Jørgen Nielsen entitled ikke/kan; and recordings of soldiers’ greetings taken from Danish radio. What most pieces have in common is a systematic or rhythmic quality. For the performance he played them one after the other, interspersed with a tape of Beuys’s own making entitled MANRESA. In a 1967 article in the magazine ta’, Christiansen wrote that ‘Bjørn Nørgaard, Joseph Beuys and Henning Christiansen played the room in a demonstration that moved along in a musical way, the first of its kind’.30

Beuys’s action consisted of a series of separate elements. In his part of the room, there were two ‘stations’, labeled ‘element 1’ and ‘element 2’. Element 1 was a felt half-cross on the wall which he completed with chalk at the beginning of the action; Element 2 was a box of electronic equipment. At regular intervals his recorded voice on the MANRESA tape asked, ‘Where is element 3?’, suggesting a quest for a way to transcend or integrate elements 1 and 2. There were various other materials in the area, which he interacted with: among other things, he made sparks with a Geissler tube and shot clumps of fat at the wall using bicycle pumps. Next to him, Nørgaard performed his own work in an unbroken flow, while Christiansen, closest to the gallery’s window, created a changing, but continuous soundscape. Photographs and descriptions give the impression of three artists simultaneously performing their work next to one another, but the contributions of Nørgaard and Christiansen added a sense of continuity that such documents can never really convey.

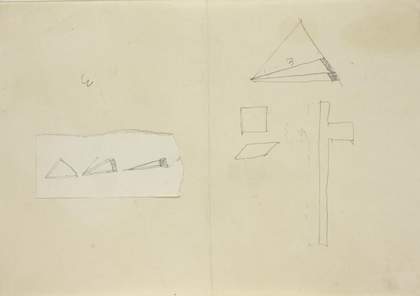

Fig.6

Joseph Beuys

Score for MANRESA 1966

Tate/National Galleries of Scotland ARTIST ROOMS AR00124

© DACS 2019

Although it consists of separate elements, Manresa has a strong conceptual consistency, and many notes and sketches by Beuys suggest thorough preparations. One drawing in the ARTIST ROOMS collection contains a sketch of the half-cross (fig.6). Thematically, the elements combine to portray the present and suggest a future. The ‘spiritual’ East (the cross) is opposed to the ‘rational’ West (the box of electronic equipment), with Fluxus/Element 3 as the flow that would have to start running between the two once again. On Beuys’s MANRESA tape, a voice says ‘Fluxus [flow] speaking’, suggesting that contact is already possible at a distance. Christiansen and Nørgaard, however, did not hear about these plans until the day before the actual performance.31 Christiansen could only guess at what would be appropriate. The tapes he chose to bring all have to do with rhythms and systems: Christiansen had spotted the way in which Beuys repeatedly explored objects and actions in his work and chose to respond with a selection of his own works that displayed the same characteristics.

Tape recorders and instruments

Sound played an important role in Beuys’s actions. Sometimes he used musical instruments, but as Jürgen Geisenberger states in his book Joseph Beuys and Music, mostly only devices such as microphones and tape recorders were used.32 Very often, it was Christiansen who provided the tapes and operated the tape recorders. Christiansen had been interested in the possibilities offered by tape recording since the early 1960s, and from the mid-1960s onwards, tape recorders began to feature prominently in his work. Works such as Please keep lay-by clean (Rastplatz bitte sauberhalten) Op. 43 1967, A Green Cube/Garden Music/Green Denmark (Un cube vert/Garden music/Det grønne Danmark) Op. 48 1968 and Music As Green (Musik als grün) Op. 51 1969–70 existed as tape recordings only.

After December 1966, Christiansen spent long periods in Düsseldorf (February–July 1967, November 1967 – February 1968, October 1968 – March 1969, April–May 1969), spending much of them with Beuys. The actions Main Stream (Hauptstrom) (20 March 1967), Eurasian Staff (Eurasienstab fluxorum organum) (2 July 1967), ÖÖ Programm (30 November 1967) and I am trying to set (make) you free (Ich versuche dich frei zu lassen (machen)) (27 February 1969) all took place while Christiansen lived in Germany. He also witnessed the founding of Beuys’s first political party, the German Students Party, on 22 June 1967, and became romantically involved with one of Beuys’s students, Ursula Reuter, whom he later married.

Beuys’s and Christiansen’s proximity changed the way they worked. Christiansen said about Main Stream (Hauptstrom), ‘Actually, Beuys and I have never agreed upon any details. He simply showed trust. I built up and tried to follow him and my own ideas’.33 The only thing that was agreed upon was that Christiansen would provide a soundscape that would ‘grow so harmonically, coherently and quietly that it would connect everything in the space’. This remark may be misleading. Main Stream (Hauptstrom) marked the opening of Beuys’s exhibition FAT SPACE (FETTRAUM) at Galerie Franz Dahlem in Darmstadt on 21 March 1967, and Christiansen had already seen Beuys work with fat during Manresa, so he probably had a fair idea of the general content of the action.

Main Stream (Hauptstrom) started with Beuys building a low wall of margarine around the performance area. The space within it was divided into two by means of a chalk line. Christiansen and his tape recorders were placed in one half, while Beuys’s action objects were scattered throughout the entire space. These included various kinds of fat: there was extra margarine to repair the wall and to create wedges in the back of his knees and in his armpits; there were wedges of fat on the floor in between which Beuys could insert his body; a hole for a heating pipe had been covered with a disc of fat; another disc of fat had been stuck to the wall and there were lumps of wax or tallow from which Beuys bit chunks during the performance. Fat surrounded the event, isolated it and was shaped during and by it. Christiansen’s description bears witness to deep knowledge of Beuys’s way of thinking:

Fat leads to an animal consciousness. Addresses us without verbosity. Without a doubt, fat touches deep psychological layers, creates direct understanding, without that which is understood creating logical sequences of words ... An instinctive form of knowledge, an instinctive certainty puts us in a new situation, or, even better, transports us to a situation that we have forgotten. A situation where status and revision impose themselves lightning quick.34

Christiansen was well aware that the manipulation of fat, in Beuys’s way of thinking, referred to the shaping of pure matter and to the expression of pure thought.35

Christiansen’s contribution consisted of five tapes with recordings of his own works that he played on five tape recorders simultaneously, creating a soundscape of changing intensity and rhythm, as if responding to Beuys’s shaping of the fat. He described it as the ‘bringing together of his earlier compositions in constellations that shift in time and conception’.36 Apart from playing his tapes, he also recited the occasional Beuysian aphorism such as ‘It is not your fault that you said it, but that they asked you’ or ‘This is my axe, that is the axe of my mother’. He no longer just chose works to fit the action, but created his soundscape on stage and added to the process of meaning-making.

The next action was Eurasian Staff, a demonstration of the division and reunification of East and West by means of a long, heavy copper rod, bent at one end like a shepherd’s crook. It was performed twice, at Galerie Nächst St. Stephan in Vienna on 2 July 1967 and at Wide White Space gallery in Antwerp on 9 February 1968; Christiansen directed a film of the latter performance.37 During the action, Beuys indicated a space by means of four felt covered wooden beams that he inserted between floor and ceiling, swept the four corners with the Eurasian Staff and took the beams down again, leaving the rod and its cover in the shape of a cross on the floor. What sets the action apart is that Christiansen composed a piece of music, fluxorum organum 82 min., especially for the occasion, the only piece that was played during the action. Action and music were directly linked; Christiansen spoke of ‘a new form of expression on the boundary between musical theatre and oratorium’ and ‘a new form of communication, a demonstration opera’.38 Unlike Main Stream, Eurasian Staff was preceded by long conversations. Christiansen said, ‘We spoke about dividing fluxorum organum in 5 parts, in the middle, during the third movement, the Eurasian Staff had to rise itself and reach the felt corners at the top, just beneath the ceiling’.39 The action was thoroughly thought-out, the elements already known when Christiansen started writing the composition. Beuys even made a drawing for him of the Eurasian Staff superimposed on the map of Europe, crossing the Iron Curtain.40

Fig.7

Henning Christiansen

Score for Eurasian Staff fluxorum organum 82 min. Op. 39 1967

© Henning Christiansen Archive, Møn

Fluxorum organum was written in May–June 1967 and recorded at the Liebfrauenkirche in Düsseldorf, with Franz Meiswinkel at the organ. Christiansen described the reasons behind the choice of instrument: ‘Organ taken out of its context (church) in order to become part of a new message that transcends the priesthood’.41 Beuys heard the tape a couple of days before the performance, so both knew what the other’s contribution was going to be; and both seem to have conceived the action in terms that were part-musical and part-visual. Beuys said in an interview: ‘I wanted a sound … that seemed to originate from the head. I wanted to achieve a movement in the brain, a work that on the one hand seemed to come from the head, the spirit, but that on the other hand has a relation with the image of expansion that is implicit in the notion of Eurasia’.42 Christiansen once again made use of alternating (architectonic) ‘pillars’ of sound and silence that are as easily recognized in the score as they are registered by the ear during a performance. In the score of the third movement, the notes can also be seen to rise up and move down again (fig.7).

However, fluxorum organum was not uniquely connected with Eurasian Staff. It was, for example, also performed live on the organ of Nikolaj Church during a ‘party day’ for the German Students Party in Copenhagen on 10 May 1968. Christiansen had tried to invite Beuys, but he was too busy.43 Instead, Bjørn Nørgaard created a ‘party landscape’ into which he introduced the shape of the Eurasian Staff. A long roll of paper was rolled out on the floor in the shape of a shepherd’s crook, onto which Nørgaard scattered various materials, objects and items of clothing; at the same time, the writer and critic Hans-Jørgen Nielsen wrote down on the floor what Nørgaard was doing. Linguist Ole Stig Andersen, co-editor of the countercultural magazine Hætsjj, made a speech during which he claimed that new times were coming, and that the new era demanded a new kind of political organisation and a new political language.44 By implication, the sober actions, everyday materials and the factual recording of the event became that new language: simple but symbolic and locked in a permanent exchange between East and West, spirit and ratio, by means of the Eurasian Staff.

Although Beuys was absent, the materials and actions echoed principles in a manner similar to his actions. Eurasian Staff and fluxorum organum were inseparably linked, but that did not mean that Christiansen’s composition could not also be combined with Nørgaard’s demonstrations. Neither inherently meaningful, like some kinds of happening, nor meaningless, like most Fluxus events, Beuys’s actions and Nørgaard’s demonstrations generated meaning by extrapolation. They provided a setting in which Christiansen’s music seemed to fit and was able to support.

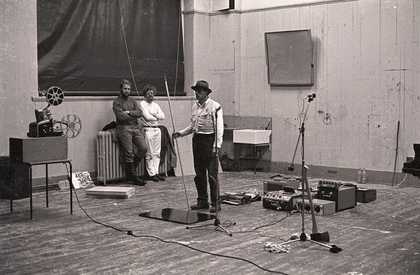

Fig.8

Joseph Beuys during the performance of Ö Ö Programm at the Art Academy in Düsseldorf on 30 November 1967

Photo © Volker Krämer

In his invitation to Beuys, Christiansen also referred to a piece entitled Party Music (Parteimusik), Opus 44. It disappeared from his opus list, but part of it was the soundscape that was created for another action with Beuys, Ö Ö Programm, performed during the annual enrollment ceremony at the Art Academy in Düsseldorf on 30 November 1967. Chancellor Eduard Trier and Professor Karl Bobek both gave a speech, but the contribution by Beuys and Christiansen was considerably less conventional. Beuys produced guttural sounds for several minutes (fig.8) and Christiansen played a new composition entitled Please Keep Lay-By Clean (Rastplatz bitte sauberhalten) Opus 38, a tape composition consisting of the voices of Christiansen and Johannes Stüttgen, a student of Beuys and German Students Party activist, repeating the title of the composition. It referred to the text of a sign that was seen in all German lay-bys, described by Christiansen as ‘an appeal to all people to be sensible and to think of others’.45 He also played fragments of And an angel walked past… (Und ein Engel ging vorbei...), his declaration of love to Ursula Reuter, and To Play To-Day Opus 25, his farewell to Fluxus. The former piece takes its title from the Danish expression ‘an angel walks through the room’ (‘der går en engel igennem rummet’), describing a quiet descending on a scene. As Christiansen writes in his notes to the piece, the first thing that is said after such a quiet spell had better be good.46 It stands for a new start, appropriately for an enrolment ceremony. From To-Play To-Day he played Buzzard, a piece for gong, bassoon, trombone, violin, cello and double bass that only lasts for 70 seconds, with long tones and glissandi. It functioned as a kind of drum roll while the doors were opened and the sound of the beat band that played outside rolled into the room – another transition, this time from ceremony to celebration.

Christiansen was also physically involved in the action. Earlier, he had primarily been present as an island of peace and quiet, manipulating his tape recorders and smoking his pipe. During Ö Ö Programm, Beuys pressed an axe with a broken shaft against Christiansen’s chest. Christiansen then took the axe from him and pressed it against Beuys’s chest. It echoes Main Stream (Hauptstrom), where Christiansen had recited the sentence ‘This is my axe and this is the axe of my mother’. Beuys explained this phrase by saying that ‘[m]y axe is different from my mother’s in so far as my struggle is different from hers’.47 The action, almost ritual in nature, sheds a different light on Christiansen’s presence in Beuys’s actions, this one as well as the ones that preceded it. Although it was Beuys who stood for most of the action, Christiansen’s role was not that of a musician. He was the originator of the music, a producer, and a creative individual. In the terms of Beuys’s axe metaphor, Christiansen too had his axe, although the shaft was broken in a different way from Beuys’s.

Precisely his presence in the performance area as a creative individual is also what characterises Christiansen’s role during the next two actions, I am trying to set (make) you free (Ich versuche dich freizulassen (machen)) at the art academy in Berlin on 27 February 1969 and …or should we change it (...oder sollen wir es veränderen) at the Municipal Museum Mönchengladbach on 27 March 1969. The two actions were essentially the same piece, but the first time around, Beuys and Christiansen were prevented from carrying it through. In a text called ‘Water Baptism’ (Die Wassertaufe), Ursula Reuter Christiansen describes what happened in Berlin in detail.48 On the day of the performance, a large number of students had been confined to the university grounds to prevent them from protesting against the American president Nixon, who was on a state visit in Berlin. Many of them had wanted to see the action anyway, but to judge by Reuter Christiansen’s text, their pent-up frustrations had put them in a more activist mood. Beuys had just made a score by draping sauerkraut on a music stand and he and Christian were just about to start playing – Beuys on the piano, Christiansen on a green violin – when the students trained the building’s fire hoses on them. After a member of staff closed the water mains, they invaded the stage and destroyed instruments and equipment. However, apart from the ‘water baptism’ alluded to in the title of Reuter Christiansen’s text, it was also a baptism of fire: the idea of art as a tool towards political transformation was tested to breaking point. Beuys saw art as a creative force that could influence reality and life directly, while the students saw life as political and art, as Reuter Christiansen puts it, as ‘capitalism’s whore’.49 Entirely in the spirit of Beuys, the discussions went on for hours.

Exactly one month later, the audience could experience the action in its entirety at the Municipal Museum, Mönchengladbach. The sauerkraut scores were made anew, Beuys played the piano and Christiansen played a normal violin, a green one without strings and a ‘Fluxorgan’, designed by George Maciunas. Apart from this, the soundscape consisted of meaningless sounds uttered by Beuys and various tapes by Christiansen. Before the start of the event, a pamphlet by Johannes Stüttgen was distributed that placed the performance in a wider context.50 It proposed a ‘plan of change’ according to ‘scientific-artistic principles’; an ‘educational plan’ that would lead to an inner revolution by means of ‘contemplation, empathy and involvement’. In culture, it would lead to autonomous labour; in politics and law, to democratic labour; and in economics, to social labour. This reorganisation of labour according to the original principles of the French Revolution, freedom, equality and fraternity, is the essence of the programme of the German Students Party. Abolition of the unitary state would open the road to self-administration, an art without state or corporate involvement, free education that focuses on free self-development, equal rights for everybody and organic collaboration in order to cover everybody’s needs.

In this context, the sauerkraut score acquired a clear meaning as pure nutrition, made available for creative interpretation. Christiansen described the green violin as a ‘new instrument’, painted green in order to make it look ‘impudent and merry’.51 Beuys’s unarticulated sounds, too, become meaningful, peeling away the limitations of conventional language to uncover basic expression and the possibility of new ways of communicating. The title, too, is drawn into this game of contextualisation and extrapolation. ‘Or should we change it’ is a question to the museum’s director: should the title be kept as ‘I am trying to set (make) you free’ or should it be called something else? In the context of Stüttgen’s text, this becomes a proposal to change society in its entirety.

Fig.9

Beuys performing Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony, with Christiansen behind (right), for the exhibition Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 23–30 August 1970

Demarco Digital Archive

These actions had been planned during one of Christiansen’s stays in Düsseldorf, but the last action that they both participated in was organised from a distance. Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony (Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Schottische Symphonie) was performed during the exhibition Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art on 23–30 August 1970 (fig.9); it was also performed later in a slightly different version called Celtic +~~~, in a bunker under construction in Basel on 5 April 1971.52 The correspondence about it is oddly factual; according to Christiansen, all the arrangements concerning the form and content of the piece were made by telephone.53 It is unclear who decided that they needed the sound of a piano being tuned, but Christiansen ordered, from his flat in Denmark, a piano tuner in Scotland. When he came, Christiansen lay down underneath the piano with his tape recorder to record the tuning process, while Beuys walked around, tapping a stick on the floor, singing and finally thanking the piano tuner. With a reference to Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony (Schottische Symphonie) 1842 (Sinfonie Nr. 3 in a-Moll Op. 56), Beuys called the result a ‘new Scottish symphony’.54 The recording was played during the first and last part of the action.

Like Eurasian Staff, Celtic was a multi-part piece. During the first forty-five minutes, Beuys sat on a chair, drew on a blackboard and walked around, tapping the floor with a stick and swinging it around. He spent the next hour and a half picking pieces of gelatin off the wall and putting them on a tray, which he then emptied over his head. During the final forty-five minutes he stood still, holding a spear-like object. As Christiansen describes it, the sonic side of the action consisted of the Scottish Symphony during the first and last part and various other pieces and soundscapes in the middle. The first thing to be played after the Scottish Symphony was Christiansen’s film of Eurasian Staff, accompanied by the first movement of fluxorum organum. Next, Trans-Siberian Railway (Transsibirische Bahn) 1970, a film recording an action performed by Beuys during the exhibition Tabernakel in Humlebæk, Denmark, was shown, accompanied by sounds recorded by Christiansen on the ferry from Esbjerg to Newcastle. After this came a piece by Arthur Køpcke called Worm in the Brain and several of Christiansen’s own compositions (Perceptive Constructions, The Arcadian (Den arkadiske), a part of Music as Green (Musik als grün)). The tapes were once again played one after the other, so the rhythm was provided by the succession of pieces, rather than by the density of the texture created by playing several pieces at a time, as in Main Stream. Alastair Mackintosh, who witnessed the action, noticed the effect of the soundscape, especially during the first part, when Beuys sat on a chair: the music, he said, helped to perceive his simple presence as part of an action.55 Christiansen was hardly involved in the action, only briefly taking the tray of gelatin from Beuys and handing it to Ernst Föll, who handed it to Johannes Stüttgen, who gave it back to Beuys.

Celtic was the last of a series of actions for which Beuys and Christiansen shared the stage. From this point onwards, they went different ways – Beuys towards a more dialogical form, Christiansen towards a new populism. Christiansen’s new dilemma, after the choice between architecture and psychology, had become that of addressing an audience without looking down on it. As he wrote in a text dated 7 June 1971, ‘That’s where the difficulties start, how to avoid looking down on people, to patronize them, to shape one’s material so that nobody reacts because one has made a wrong choice and how does one avoid a commotion about the wrong sides of a work’.56 One of the pieces he played during Celtic, Satie on the High Seas (Satie auf hoher See) Op. 52, already pointed in this direction. This was not a systematic piece, like the Perceptive Constructions or the later The Arcadian, but an encounter with the French composer Erik Satie and his knack for musical story-telling. It hints at waltz music, and this was indeed a form that Christiansen embraced during the years that followed. He began to compose film music and wrote songs for the Danish communist party. The simplicity that characterises his work of the latter half of the 1960s offers itself to intellectual understanding but now there was a message that needed to be communicated; and Christiansen devised vehicles for it that went straight to the senses.

fluxorum organum and Fluxorgan

The above account of Christiansen’s involvement in Beuys’s actions during the period 1966–71 may give the impression that they always worked together, but that is not the case. Not only did Beuys produce countless objects away from performance, he also staged several actions that Christiansen did not take part in. Titus Andronicus/Iphigenie, for example, performed in the context of experimenta 3 at the Deutsche Akademie der Darstellenden Künste in Frankfurt on 29–30 May 1969, was a solo action. Tape was used, but it contained excerpts from Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus and Goethe’s Iphigenia in Tauris (Iphigenie auf Tauris) instead of music/sound. Christiansen, too, had separate projects. As already mentioned, he enjoyed success as an important representative of the ‘new simplicity’. More directly relevant for this essay, his ‘opera’ Nice weather, isn’t it, Ibsen? (Dejligt vejr n’est-ce pas, Ibsen?) Op. 37 1966 gives a fair impression of scenography responding directly to Christiansen’s music. The opera, with a libretto by Hans-Jørgen Nielsen and a stage design by Bjørn Nørgaard, is rigidly organised in every aspect. The action takes place among the audience in a set consisting of four concentric circles. The four singers each have their own costume, object, shape and way of moving. The soprano wears a ‘romantic dress’, holds a silk handkerchief and is has a red wooden box as her attribute; the alto is dressed as a nurse, holds a rose and has a white cylinder as her attribute; the tenor wears baseball attire, holds a ball and has a green pillow as his attribute; and the bass wears workers’ clothes, holds a yoyo and has a plastic cone as his attribute. The poses they always return to are standing (the soprano), sitting (the alto), reclining (the tenor) and lying down (the bass). Both the libretto and the music are circular: scene 1 is the same as scene 5, scene 4 mirrors scene 2 and scene 3 is the point of balance. As the introduction to the score puts it: ‘The shapes are sounds, the movements are the time between the sounds. Just as the music, the sounds and the text move around in a circle, the singers move through all the forms and back to their original starting point’.57

Christiansen was not happy with the term ‘new simplicity’, which, as he wrote to musicologist Jan Maegaard in December 1965, to him suggested the transposition of everyday situations to the ‘universe of the poet’.58 That was not what he wanted. His simple movements were designed to enable the listener to perceive the work’s general shape: ‘A number of rules are formulated [and] these rules have to be so clear to the listener that s/he does not get lost in a jungle of complexities but clearly perceives the work’s general shape as a result of the rules’.59 He suggested ‘Neo-constructivism’ as a more appropriate term.

Christiansen wanted his music to be anonymous, conscious, controllable (for the listener) and mechanical. He was happy to sacrifice expression, vitality and entertainment if it made it easier for the listener to assess the work’s idea and ‘pattern’. In one statement from the mid-1960s he wrote:

Music is there to be heard. A sound is a sound. The interval between two tones is the interval between two tones. These factors move music into reality, a long way away from dream and metaphysics. A reality in which experience is the only thing. Present music. Concise music. Music as object. Music as its own reality.60

He also wrote, in another statement from the same period, that ‘Music is not a matter of philosophy, but something direct. Perception and imprint are essential. Models (Modeller) Op. 33 establishes new ways to organise time. Long pieces aim to establish situations, short ones spread out through memory … visual music – imaginary architecture’.61

It is hard to see where his work together with Beuys fits in this tightly controlled world. A clue is given by a text that Christiansen wrote in 1968, called ‘Also a false interpretation (I II III IV)’.62 It describes four ways of understanding Beuys’s work which are ‘false, but not incorrect and particularly not irrelevant’. Interpretation I returns to the notion of the ‘anti’ that played such an important role in Christiansen’s first piece on Beuys from 1966, only now as the opposition between reality and poetry. Reality simply presents itself, he writes, and only poetry can reveal it as one side of an oppositional pair; Beuys communicates this insight, according to Christiansen, by means of his materials and procedures. Interpretation II describes Beuys as a ‘material poet’ who communicates principles via his choice of materials and procedures, downplaying the object quality of the result and stressing the element of transformation. Interpretation III describes Beuys as an artist who employs existing genres such as sculpture in ways that frustrate codified ways of understanding them, thus pointing towards his idea of anti-space as a space within oneself yet to be explored where transformation is possible. Interpretation IV describes Beuys’s activities as ways of making physical reality coincide with poetry as its opposite. His actions, Christiansen writes, are object-based and therefore exterior to man, but their effect is to cast objects and actions as the opposite of poetry and thus to cause anti-space to open itself up within the viewer. In this sense, the German Students Party is just as much a work as any action, because it is a phenomenon in the outside world, but a mental space as well, and capable of transformation in the same way as an object or an action.

Nowhere does Christiansen explain why his four interpretations are ‘false, but not incorrect and particularly not irrelevant’. The very form of the text seems to be chosen to underline the fact that no single approach can ever explain the ‘why’ of Beuys’s work. However, it is apparent that the four interpretations are linked. In the first, he claims that only art can reveal reality as reality; in the second, he explains that the manipulation of reality in action is as significant as the result; in the third, he states that change can only be brought about by presentation and manipulation of the known; and in the fourth, he claims that real (objective) actions can have an effect on the subject. The revelation of reality in poetry leads to the manipulation of reality as significant action, which in turn leads to the possibility of change inherent in manipulation/transformation, on the basis of which it is concluded that action can change people. The text acts as a quadruple lens that powers an argument in favour of social change through art.

Fig.10

George Maciunas

Fluxorgan c.1966

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2019 George Maciunas

One detail serves to show how the article can be used as a key to the question of Beuys’s and Christiansen’s co-presence on stage. The sound for both Eurasian Staff and …or should we change it? featured an organ; in the former sound work, fluxorum organum, a church organ was used, while the latter employed a Fluxus version – the ‘Fluxorgan’ (fig.10). The sounds they produced could not be further apart, and neither could their respective connotations. On the one hand are the rich tones of the organ that echo in the huge space of a church, taped and therefore transportable to other spaces with completely different acoustic properties. Fluxorum organum is played on a highly respected musical instrument, but detached from its usual context and thus opened up for other connotations. On the other hand, the Fluxorgan is a box with rubber bulbs that only produces random honks and whistles until one has worked out which rubber bulb produces which sound. The instrument is typical of George Maciunas’s idea of Fluxus: it was cheap, could be bought by mail order, was playable by all and ridiculed the idea of ‘high’ art as a product of genius.

In fluxorum organum, the oppositional pair reality/poetry (interpretation I) is played out as the opposition between the notes as they were played on the organ and Beuys’s invocation of the four points of the compass; perceived sound is contrasted with a poetic (imaginary) ‘touching’ of space, a material present with a poetic sketch of a future space. In terms of the opposition between material and action (interpretation II), they are musical notes, but they are preserved on tape, made repeatable and transportable – what they are is less important than what can be done with them. If one looks at it from the point of view of expectations (interpretation III), it is clearly music, but the link with the action is equally inescapable – as the Eurasian Staff is raised, the sound is heard to go up and the notes on the page are seen to go up. Finally, in terms of subject-object relations (interpretation IV), although it is music one hears, and everybody knows that music is traditionally to be enjoyed while sitting down in a concert hall, it is presented in a context that both materially and poetically suggests movement and the transcendence of the listener’s time and space.

The Fluxorgan, however, although very different from the recorded church organ, is used in very much the same way. Here, the material honks and whistles are poetically coupled with a vision of pure, uncodified communication (I). It is played, but the act of playing it is more important than the result (II). In combination with the sauerkraut score and the green violin, it hints at the possibility of stripping cultural habits away, finding a human core and rebuilding culture from the inside out (III). An audience expects either music or a performance, but gets neither, because the sound is difficult to control and the action invisible – hidden in the box, hidden in the musician (IV). The audience is confronted with live action and real sound, but invited to extrapolate from these to a future where sounds that might seem like random noise in the present can be perceived as human communication.

Conclusion: framing and the double negation

For Christiansen, then, framing his practice as a composer in the context of the Beuysian action makes it possible to explore aspects of his own work that are not normally available for inspection. His insistence on the overall shape of the work and its easy recognisability was cast in opposition to drama, narration and process, but that does not mean that they are irrelevant. Christiansen’s neo-constructivism stresses the reality of the piece rather than its poetry; the act of listening rather than the act of composing/playing; the revolt against traditional practice rather than its renewal; the music’s objective qualities rather than its effect on the listener. Within the time and space of Beuys’s actions, Christiansen’s music could become part of a reflection on the narrative potential of notes and structures, on the function of music as a spatiotemporal modelling tool and/or on the possibility of extrapolation, by the listener, to other cultural phenomena that are not, strictly speaking, musical. If his music in the context of his own practice as a composer made the point, it explored possible futures in the context of his work together with Beuys.

Christiansen saw his work as ‘visual music’ and ‘imaginary architecture’.63 The structures he created were as easy to recognise on the page as they were to discern by ear in a performance setting. In his work together with Beuys, however, it is the architectural side that gains the upper hand. His sound permeated the entire action, structuring it and during quiet moments perhaps also carrying it. When the two agreed on a strategy beforehand, the sound followed the structure of the action, underlined it and materialised it for the audience. Just like Beuys’s actions, the music introduced elements: space as acoustics; sound as the raw material of expression; structure as the act of structuring; manipulations on stage as creative activity. It was presented, manipulated and transformed poetically. From taped recording to the live playing of tapes and the composer’s presence on stage as a creative individual, it illustrated principles that also motivated and shaped Beuys’s actions and that were to be transferred to the audience.

The double negation might well be a more useful way of describing Christiansen’s presence in Beuys’s actions than the affirmative. What is at stake is neither the complete incorporation of Christiansen’s sound into Beuys’s actions nor a clash in which one or the other will always end up seeming incorrect for the context. What is at stake is not absorption or conflict, but a meeting marked by non-irrelevance; a double negation, in other words, that suggests co-existence and the possibility of nuances to either side. Not, as already noted at the start of this article, the model offered by Fluxus or happenings, but a form that finds its significance in flows and extensions of conceptions.