Traditionally, an artwork has made its way from the studio through a dealer and into a private collection or museum. However, in the late 1960s a number of artists sought new ways to distribute work outside this system. Some used the mail, be it producing postcards (Eleanor Antin) or envelopes covered with arrangements of stamps (Alighiero e Boetti). Others exhibited on street corners or placed their works into other artists’ exhibitions without permission (André Cadere). During the same period, artists found new ways to address current catastrophes. They realised that the politics of a work involved more than just its overt subject, but the very mode and place of presentation. In New York, the Art Workers Coalition produced a poster featuring an image of the My Lai massacre, and took it into the Museum of Modern Art. Holding copies beside Picasso’s Guernica, they read out statements and drew parallels between the Luftwaffe and the American army in Vietnam and re-politicised Picasso’s painting, whose initial charge had been dampened in its museum context.

Cildo Meireles’s Insertions into Ideological Circuits, begun in 1970 during a period of intense political oppression in Brazil, were similarly radical. Meireles found a means of disseminating art without the gallery system. He took returnable glass Coca-Cola bottles and printed political messages on them, including “Yankees Go Home”. Almost invisible when empty, the messages became more legible when the bottles were refilled at the factory. With no knowledge of the artist’s action, Coca-Cola would then distribute the altered bottles to new, unsuspecting customers, with Meireles remaining invisible as their author. While piggybacking an existing commercial mode of distribution, he undermined the ideology of the company – Coca-Cola exemplified the entry of American brands into the Brazilian economy. Meireles also worked with banknotes, stamping on slogans of various kinds, including some referring to recent political murders, before returning them into circulation.

Cildo Meireles

Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project 1970

Collection New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York

Transfer text on glass

25 x 6 x 6 cm

Photo: Wilton Montenegro © Cildo Meireles

These works will feature in Meireles’s Tate exhibition. With this in mind, I asked three artists to describe projects in which they have used the strategy of insertion. Omer Fast altered soundtracks on rental videos and returned them to shops, which continued to rent them out. Carey Young has worked with marketing devices in order better to examine corporate values and processes. For their project Google Will Eat Itself, ubermorgen.com and Alessandro Ludovico used Google’s own technology to prey on the search engine. Sometimes these artists utilise existing modes of distribution, as did Meireles; in each case they target ideological systems, whether those of Hollywood film, global brands, or online information providers. As Young makes clear, these artists are not naively attempting to halt the activities of global capitalism or the culture industry; instead, they use insertion the more effectively to analyse and shift understanding of these activities.

Omer Fast on T3-AEON

During the summer of 2000 I was home a lot, looking for things to do and watching TV. Air France 4590, the last Concorde flight, crashed shortly after take-off from Paris. President Clinton hosted Yasser Arafat and Ehud Barak for talks at Camp David. The Russian submarine Kursk exploded and sank in the Barents Sea. The Republican Party nominated George W. Bush as its candidate in a national convention. And parents in Arizona discovered clips of hardcore pornography dubbed on to movies they had rented for their children from a local video chain. A new millennium began on TV, not yet with a bang – that would come in 2001 – but with a series of whimpers.

The man responsible for the porn clips in Arizona was tracked down and arrested, but like most idiots and visual artists who spend too much time at home, watching TV and looking for things to do, his problem may have been more social than occupational. Anyway, whatever else the man’s problem may have been, it finally got me off the couch, out of the house and into a Blockbuster™. Trawling the aisles, I obviously stayed away from the kids’ section. In our culture, criminals and artists must be original. Copycats of any kind are despised. I also avoided the new releases. Video stores, like libraries, get most of their business from a small slice of their inventory. The rest just stays on the shelves and hardly ever gets handled. I was looking for something violent, stylised, even cartoonish, but nothing new or so popular that my art project, whatever it turned out to be, would be quickly discovered. The problem is I always experience amnesia in video stores. I can never remember even one of the hundreds of important movies I’m supposed to watch.

The Terminator by James Cameron was released in 1984. It was one of the first films I saw after moving to the States. The film is about a psychopath from the future who takes steroids, runs around killing people, cuts his own eye out, marries a Kennedy and then runs for office as governor of the world’s eighth largest economy. It made a huge impact on me. After seeing the movie, I made my father buy me a huge exercise machine at the mall, which we drove home in pieces in our new Oldsmobile station wagon.

T3-AEON was a public art project that involved altering the soundtrack of The Terminator movies rented from New York area video stores. The alteration consisted of four short interviews that were dubbed on to the soundtrack at four different points. In each segment, an off-camera voice recalls an incident from early life that involved being physically disciplined by a parent. Nothing traumatic, just the normal stuff that happens in families where hands, belts and a stick are used for disciplinary purposes. The voiceovers were inserted into the movie during scenes of intense violence, temporarily giving the action an alternative intimate meaning, but otherwise allowing the film to continue with its plot dynamic intact. As a group of stories smuggled into rented cassettes, the four voiceovers present a hidden record whose purpose is to communicate its content and survive. In the end, though, the material survival of this record in circulation depended on how well it interfaced with its host – The Terminator – and on its future relationship with an unknown and unsuspecting audience. I really hoped viewers would appreciate the stories and return the tapes without complaining. There was no way to find out. A tiny sticker affixed to each cassette allowed a quick check on the status of the project. In August 2001 I moved to Germany and stopped checking. Within a year the entire inventory of videocassettes at all stores was replaced by DVDs.

Carey Young

I have been collecting slogans about corporate creativity for the past decade. It’s a little like building some vast textual graveyard of the imagination stone by stone, except this is no mausoleum: such slogans express corporate vision for the future – a desire to be associated with innovation, artistic endeavour and the avant-garde. This image of imagination allows firms to suggest they have a handle on the future, and, as a result, a greater market worth. The slogans have not only accumulated on my computer like a virus, they are also everywhere outside it: in advertisements, on TV, in public spaces, in our galleries. Think Different. Invent. Imagination at work. Where imagination begins. It’s not that hard to imagine. A repetitive beat, an echo: the sound of the market’s systems and images in endless call and response.

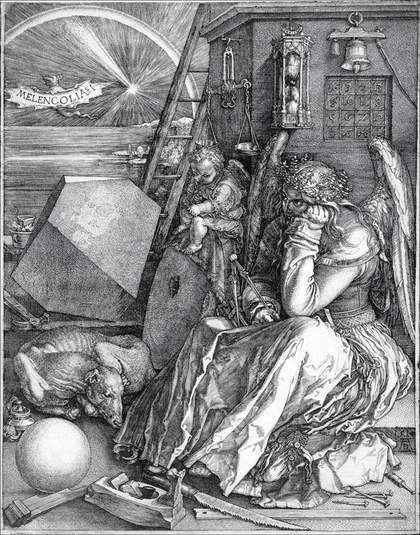

The strange thing about these slogans is, in fact, that most are very hard to remember. I made a work about this: Product Recall 2007, a short video set in a psychoanalyst’s consulting room. I fabricated the room, complete with wall-mounted Persian rugs and framed monochromatic prints (in this case, a print of Dürer’s Melancholia 1514) and typical of Freud’s with the old furniture and academic clutter of the average cinema or TV shrink. The analyst gently tests my ability to recall the company names associated with a number of catchphrases around creativity. All are from real ad campaigns of globally recognised brands, most of which are active as sponsors of art institutions, fairs and exhibitions. During the session, which seems part of an ongoing relationship between the analyst and myself, it remains unclear whether the point of the exercise is for me to remember or to forget the material. The fact was, whether acting or not, it proved impossible for me to recall many of the slogans. They all sound the same. The quasi-fictional realism of the piece is intentional – the audience will also find themselves able to remember some slogans and not others, simply because the brand statements are so bland. It has struck me that if we are looking for ways to resist corporate influence, one small method may simply be not to remember the advertising messages.

Albrecht Dürer

Melancholia c.1514

Engraving

24.1 x 192 cm

Courtesy The British Museum

Cildo Meireles has been an inspiration for my work for about the same decade. His Insertions imply hope in our systems-orientated era in ways which have only become more prescient. The idea of an artistic intervention, with its implication of stoppages and blockages, has always seemed a little naive to me. Why is this word so overused in connection with art? I hope I am not being over-literal when I ask: since when did an artist actually stop anything to do with mainstream capitalism? Insertions seems a much more useful and provocative term. It implies that the artist has the knowledge and the tactical cunning to define a system (perhaps by combining disparate systems) in formal, conceptual and indeed rhizomatic terms, and then find a gap from which to insert or divert something which reframes an understanding of the whole. Such a tactic exposes and manipulates the dynamics and asymmetries of power around us: a form of kinetic art employing a systems aesthetic. This is art as software: it implies a potential reprogramming of the physical and the immaterial. We should explore this model further.

Alessandro Ludovico

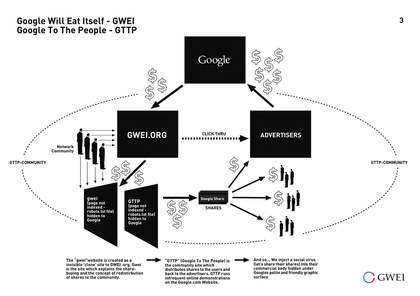

In 2005 I developed the project Google Will Eat Itself (GWEI) with ubermorgen.com and Paolo Cirio that was based on a simple but effective hack. We established a fake website about online marketing and subscribed it to the Google AdSense program, which lets you publish Google-served textual advertisements on your website. Google would then pay a small amount of money for every click by visitors on such advertisements. Then we opened a Swiss bank account that automatically bought Google shares as soon as the sum obtained with the AdSense program reached the latest share price. So, in a way, Google was giving us the money to buy itself. After a while it shut down our first AdSense accounts, so we developed a software that automatically made so-called “fraudulent” clicks every time a visitor accessed the website. It was accomplished at simulating average visitor behaviour. And it definitively worked. However, let’s remember that GWEI is a conceptual artwork. And as one Village Voice journalist noted in his review: “At the current rate we’ll need more than 200 million years until GWEI fully owns Google.”

But let’s analyse what I call “Google self-referentialism”. Google knows how to entertain the people. For most internet users it is the first point of reference. It uses a kind of “porcelain interface” – perfectly shaped, rounded, familiar, shiny and funny, exploiting the common perception that it is a public service. It plays a metaphorical game: being almost the only reference for everything. So it becomes self-referential. How did this happen? Google grew until it was the most important search engine. It then established a web filter criterion (page ranking that determines which pages go first in search results). But the page ranking system is not an open scientific criterion. It is a secret. So in the end it decides (indirectly) what content will come up first on page results.

Advertisements are another crucial element of Google. It is the biggest player in the net advertisement business (actually, this is its core business). It attracts billions of users whose eyeballs are looking at its pages, which include textual advertisements that everybody can fairly buy (AdWords). On the other end many people have become publishers, for example through the giant blog phenomenon. So they are entitled to share the bits of profits through the AdSense program. They accept to display these tiny text advertisements in exchange for a small amount of money for every click on them. So Google becomes the great middleman. It takes money from the advertisers offering a targeted portion of the global webspace. And it gives spare change to the publishers for their collaboration. But we’re not talking about a natural system. We’re talking about business and predominance. Google’s position is predominant in the same moment it enters a new business field with a new service (such as gmail). It’s the Google effect: creating consensus on a new business. The greatest enemy of such a giant is not another giant. It’s the parasite. And GWEI is an exemplary parasite.