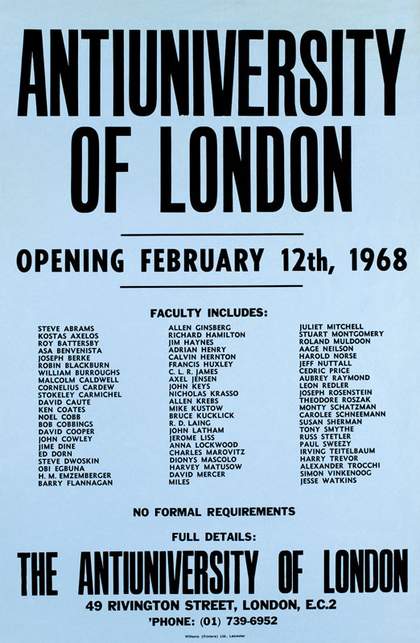

Poster announcing the opening of the Antiuniversity of London 1968

Photo: Rod Tidnam, Tate

Courtesy Andrew Sclanders/Beatbooks.com

How to begin? At a chosen moment in a vacant country house (mill, abbey, church or castle) not too far from the City of London, we shall foment a kind of cultural “jam session”: out of this will evolve the prototype of our spontaneous university… We envisage an organisation whose structure and mechanisms are infinitely elastic; we see it as the gradual crystallisation of a regenerative cultural force, a perpetual brainwave, creative intelligence everywhere recognising and affirming its own involvement.

Rousing words from the drug-addled Scottish novelist Alexander Trocchi in his 1962 treatise Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds. His ‘spontaneous university’ may have been as short-lived as a crack high, but the intensity of his vision provided the blueprint for numerous counter-cultural initiatives of the late 1960s, including the Anti-University of London, the Arts Lab and the Artist Placement Group. In their different ways these were all attempts to break down the hierarchy between art and life, to create spaces of dialogue that would lead to new forms of learning. Jim Haynes, founder of the Arts Lab, described the radical fluidity and utopian ambition of his cinema/gallery/tea room/general hang out:

People flowed through – young, old, fashionable, unfashionable, beautiful, bored, ugly, sad, aggressive, friendly – five bob if you can afford it, less if you can’t. They asked, “What’s the product? What’s its name?” The real answer was Humanity: you can’t weigh it, you can’t market it, you can’t label it, and you can’t destroy it. You can touch it and it will respond, you can free it and it will fly, you can create it and it will grow, if you kill it – it’s murder.

The burgeoning of relational art practices in recent years owes much to these pioneering initiatives. There is what we might call a pedagogical turn in contemporary art, with collaborative or research-based art enjoying a prominence it hasn’t seen since Joseph Beuys established his Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research in 1972. Two examples from recent years are the Copenhagen Free University (CFU), an artist-run initiative operating between 2001 and 2007, and Oda Projesi in Istanbul, officially active since 2000 but informally operational for a few years before that. The CFU produced small publications, hosted discussions, organised participatory events and ran a community TV channel. Its founders, Henrietta Heise and Jakob Jakobsen, described themselves as concerned with ‘how knowledge can be turned into life’. Their rhetoric echoed the spirit of the Situationist International, of which they saw their project as a continuation: ‘We work with forms of knowledge that are fleeting, fluid, schizophrenic, uncompromising, subjective, uneconomic, acapitalist, produced in the kitchen, produced when asleep or arisen on a social excursion – collectively.’ Like the CFU, Oda Projesi, literally Room Project, was initially based in a flat – from 2000 to 2005 – and aims to find new ways to bring together the daily life and art practices of the three artists who run it – Özge Açıkkol, Günes Savas and Seçil Yersel – with communities in the neighbourhood. Projects so far have included picnics, dances, swap-shops and a radio station.

Meeting of Artists’ Placement Group led by John Latham (centre) and Joseph Beuys (with hat) at documenta VI, Kassel 1977

Photo: Caroline Tisdall

Courtesy Tate Archives © Edition Staeck

The ambition for a more porous relationship between cultural activity and public space has a long history. Rewind for a moment to the very first institution for higher education – Plato’s Academy established in Athens in 387BC. Imagine a park filled with trees, statues and temples. Picture a few athletes messing about with discuses or javelins and, nearby, clusters of students in togas discussing love, politics or death. It was, in its own way, exactly the kind of cultural ‘jam session’ Trocchi imagined. This was a school where you could go to explore how to be a good citizen, a good lover, a good parent. The style was informal, but the substance was rigorous: ‘Our discussion is on no ordinary matter but on the right way to conduct our lives,’ Plato explained.

The philosopher believed the meaning of life could and should be studied. Yet if you went to any university, museum or other cultural institution in the UK today and said you’d come to study ‘how to live’, you’d be politely shown the door. Why should this be considered so ludicrous? Surely the question of how to live is still the most important one we can ask. Last year Anthony Kronman, professor of law at Yale, published a passionate polemic, Education’s End: Why our colleges and universities have given up on the meaning of life. ‘Why did the question of what living is for disappear?’ he asks. ‘Our lives are the most precious resources we possess and the question of how to spend them is the most important question we face.’

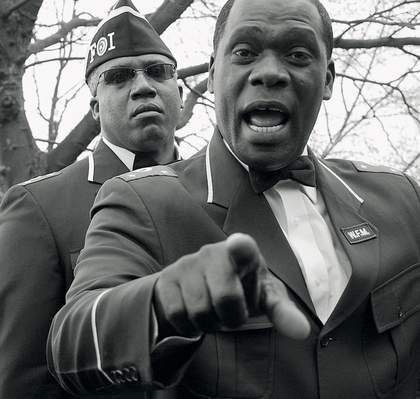

A member of the religious group Nation of Islam at Speakers Corner, Hyde Park, London 2007

Photo: Adrian Oxbrow

Kronman believes that universities can teach students to think more deeply about how to live, but that a series of historical developments have eclipsed the confidence of academics to lead such discussion. At fault, he says, are three trends: a narrowing idea of what constitutes research in the humanities, an anaesthetising culture of political correctness and the fashionable postmodern conception that all ideas are equally valid. All ideas are not equally valid. Some are without doubt better than others. And Kronman is right to argue that universities should reinstate a curriculum in which students engage with the great ideas of Western thinkers present, past and future. This is politically unfashionable, but it is possible to embrace pluralism while still recognising some common aspects of the human condition. Consider the texts selected for Penguin’s two recent series of Great Ideas. Augustine and Freud, Machiavelli and Nietzsche: these are not people whose advice for living we would necessarily want to follow, but reading them enlarges our thinking and better equips us to answer the ‘exquisitely person-al’ question of how we want to live our own life. As Simon Winder, editor of the series, explained: ‘These are Great Ideas rather than necessarily Good Ideas… They have inspired debate, dissent, war and revolution. They have enlightened, outraged, provoked and comforted. They have enriched lives – and destroyed them.’

Today, many of us vote without recollecting why we have the political systems that we do, choose our jobs by accident as much as design and get married without knowing how such an institution came into being. Our lives are our answers to Plato’s question – what is the right way to live? – but our education fails to provide us with the means to think wisely and deeply about it. Once at the university of life we have to screw up in order to learn how to do things better. But what if we could gain more wisdom through conversations and less by hard knocks? What if we could access the insights and experiences of previous generations?

Last year I started work on a school in which a wide sector of the public could access culture – specifically art, literature, film, music, history, psychology, philosophy – as the source of ideas for living. I drew on a wide range of influences, from the political theatre of Augusto Boal and the conversation meals organised by Theodore Zeldin to the Mobile Academy conceived by German curator Hannah Hurtzig; from the Flying University (active in Warsaw at the end of the nineteenth century) and Black Mountain College (where so many mid-twentieth-century American artists cut their teeth) to the maverick 826 learning centres created by Dave Eggers. Writers, artists, academics, actors, preachers and psychotherapists all formed part of a ‘fluid faculty’ that focused on five subjects – work, play, family, politics and love. From our London base, we use the city as a guerrilla campus, discussing the history of romance in a Travelodge or the contemporary relevance of Marx in the Unison office. From the outset, The School of Life has been both a utopian and a pragmatic endeavour. I hope it will become, in a small way, a recognised part of the extraordinary tradition of alternative education in the UK, which can proudly count The Open University (originally conceived of as a University of the Air) among its successes. It owes much to the vision of many short-lived (and sometimes never realised) artist-led projects which have sought to close the gap between art and life.