A dark, overcast day. Or is it evening? Or even early morning? Is a storm gathering? This painting does not tell us exactly. And then there is that narrow, sand-coloured strip: no doubt a section of Baltic shoreline, near Greifswald perhaps, which still belonged to Sweden at the time. And the figure standing there in a black overcoat, gazing out into the distance? There were certainly no tourists yet in this area in 1809. In fact the figure is the painter, Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840). Even facing away from the viewer and at some distance, he is recognisable by his flowing, reddish-blond beard. It was the whispering zeitgeist that came up with the title Monk by the Sea.

The artist as monk was entirely in keeping with the trend of German Romanticism. At the same time that Caspar David Friedrich was painting Monk by the Sea, in Vienna a group of art students were forming the ‘Lukasbund’ – the Brotherhood of St Luke. Friedrich Overbeck, Franz Pforr and some more of the faithful moved to Rome. Having first found lodgings in the Villa Malta, they spent the next two years in St Isidoro, a monastery founded by Irish Franciscans. Following the turmoils of the occupation by Napoleon’s troops, the only monk still living in the monastery was one Brother Guardian. Here the young artists settled into their own romantic version of monastic life and addressed each other as “Brother”. Mockingly, the local residents gave them the name they are still known by among art historians today: the Nazarenes. With their flowing locks, these unworldly young men put outsiders in mind of Jesus of Nazareth. And in their luggage they had a book that encouraged them to adopt this monkish demeanour – Outpourings from the Heart of an Art-Loving Monk, published in 1797 by Wilhelm Wackenroder and Ludwig Tieck, which tells of an artist, a pious wanderer who gives his all in his search for an ideal of beauty to which he swears eternal allegiance.

With the artist as monk very much in tune with the mood of the time, it is not surprising that in 1810, at the age of 36, Friedrich at last achieved success with this painting at the exhibition in the Berlin Academy. It was hung to great effect next to his Abbey in an Oak Forest 1809–10, which shows a ruined abbey and oak trees against the sky at twilight. The fifteen-year-old Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia was very taken with these two paintings and bought the pair for 450 talers. They are still in the collection of the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin. They were also much admired by leading Romantic writers and poets: Ludwig Achim von Arnim, Heinrich von Kleist and Clemens von Brentano wrote a hymn to them in the form of a series of dialogues replicating the nonsense spoken by some members of the public looking at paintings. Having laced their efforts with Romantic irony, the poets conclude by declaring how good it is that paintings do not have ears. However, their text also makes one thing clear: the core meaning of Friedrich’s paintings lies in the viewer’s own interpretation, and there is nothing in them that does not already exist in the viewer’s heart and mind.

The institution of art as a monastery: philosophers in Germany in the early 1800s liked to toy with this metaphor. Friedrich Schlegel defined art as an ‘aesthetic church’, and in the modern era – since Romanticism – the emotions associated with religious devotion have increasingly come to resemble those generated by the aesthetic experience of viewing a work of art.

Caspar David Friedrich

Self-Portrait 1810

Chalk

23 x 18.2 cm

Courtesy bpk Berlin/Jeorg P Anders/Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

The Caspar David Friedrich Effect

A self-critical digression: when I, in this day and age, write about a 200-year-old painting, I know more than the people thinking about it back then, more even than the artist. As time passes, the meanings to be found in a work of art increase in a manner that its maker and the wider public could never anticipate. In the case of Monk by the Sea, it took 150 years before it achieved the great fame it enjoys today.

After his initial success, Friedrich had to live with the fact that his brittle Romanticism had soon outstayed its welcome. During the Biedermeier era and the Gründerzeit, the preference was for a cosier style, for more stories, for something more sentimental. With his work having fallen entirely out of favour towards the end of his life, it was not until the renowned Jahrhundertausstellung (Century Exhibition) in Berlin in 1906 that the first Friedrich revival took off. However, his new standing was soon absorbed into the philistinism of official Nazi art. Friedrich’s blond Monk by the Sea became an Aryan soldier with a Faustean longing for the cosmos, aware that he was a member of a “nation without space”. In fact the Nazis’ instrumentalisation of Friedrich’s work meant that for decades after the war it was not deemed socially acceptable. It was not until 1975, when Werner Hofmann presented his Hamburg exhibition, that the next phase of Friedrich popularity finally got under way.

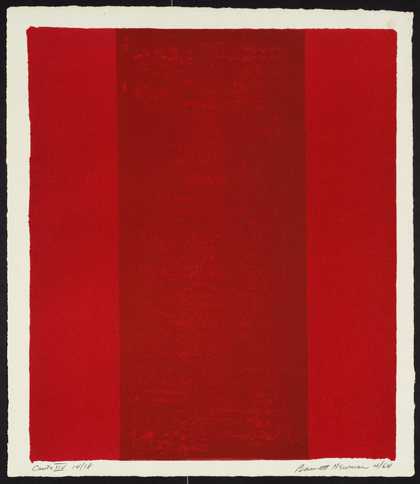

Fifteen years earlier there had already been the beginnings of a revival in the United States, in the country that, as one of the Allied powers that had defeated the Nazi regime, could not be suspected of nationalistic longings. Moreover, in the United States there was a very different view of German Romanticism, which was strategically deployed by American artists and critics as the basis of an alliance between landscape painting and Abstract Expressionism designed to cut out the École de Paris as the leading art centre. In an article published by ARTnews in February 1961, Robert Rosenblum set out a genealogy tracing Colour Field Painting back through J.M.W. Turner to Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea. In the same issue there is also a studio photograph of a group of people contemplating Barnett Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis 1950–1. Evidently, the idea was to create a C.D. Friedrich effect: the Romantic confrontation of the ego and the cosmos is transposed into the white cube of the gallery. The sea has become a painted canvas, the monk a visitor in an art gallery.

It was in 1967 that Michael Fried criticised the fact that the new paradigm of contemporary art was a form of art dominated by the ‘theatricality of objecthood’. What had previously been portrayed by Friedrich in his Monk by the Sea was now a primal experience to be had by the art viewer. And the extended concept of art did not stay within the confines of the white cube. Soon there was a fad for fanciful photographs of artists posing in bleak landscapes, as though they had personally created their desert surroundings. The ego and the cosmos are presented in situ and artworks become earth works. Metaphors for the sublime, first invoked by Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant – oceans, thundering waterfalls, storms – are no longer represented pictorially, but rather translated one-to-one as real-life spectacles. The contemplation of works of art now takes the form of an aesthetic pilgrimage, with the viewer – like the monk by the sea – following the artist into the Arizona desert, perchance to Walter de Maria’s Lightning Field 1977.

Thus the art religion that was German Romanticism lives on in Abstract Expressionism, in the exegetic literalness of Minimal art and in the pilgrimages made to the sites of Land Art. With the Americanisation of the art world after 1945, when paintings from New York arrived in European galleries and museums – along with the Candy Bombers and the Marshall Plan – the Art-Loving Monk, now with an American twang, returned to the homeland of Romanticism.

Friedrich’s contemporary, Hegel, saw his own time – the Romantic era – as a phase when the ego and the world were diverging. In art this division was reflected in the heightened subjectification of the inner-self and the concurrent objectification of the outside world. In Monk by the Sea there are few objects, other than a greyish-blue sky and the expanse of sea.

In his meticulously exact self-portraits, Friedrich showed himself capable of self-scrutiny. Ruthlessly, almost ridiculously, he portrays himself staring intensely at his own reflection. His gaze is clearly all about self-referential seeing: ‘Aha, there I am in the mirror, a reverse image of myself coming at me. So that’s what I look like when I turn my full attention on things.’ This artist observes the world very closely. Which is precisely why he finds nothing other than this nothingness around him. And in so doing, he shows that he is a modern human being – a modern subject – for whom the world is no longer mirrored in his mind.

Philosophy as proposed by one such as René Descartes was permeated with the conviction that not only is an object imbued with meaning by the person reading it, the person also acquires a mirror with which to read him or herself: I read the world, therefore I am. By contrast, for me as a modern human being the perception of an object informs me only of my own extent. The subject meets its match in the things it encounters around it. Descartes’s ‘I think, therefore I am’ becomes ‘I perceive, therefore I exist.’

Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea is a metaphor for the defenceless, top-speed collision between the ego and the cosmos, subject and substratum. But this alone is not enough for Friedrich. In putting it to us he also shows us how we should view the world. He challenges us to do as he does without bothering him. We are to stand there and gaze at his painting just as the monk is gazing at the sea. The monk looks as though he is completely absorbed in his own thoughts, but he only looks as though he hasn’t seen us. In fact, by his demeanour he is saying: “Follow me; feel what I feel. Somehow you will know what I feel. And if you don’t, then you’re just bothersome, and you’re not equal to myself. In which case, turn away and leave!” The Romantic artist does not have a message for all of us. He reveals himself only to those who know they are his kindred spirits.

Caspar David Friedrich, in the guise of the monk, plays the part of the observer who addresses us, saying: ‘May you, too, be just such a monk.’ Friedrich’s own view is well known: close your eyes and your inner eye will see all the more clearly. So I obeyed the painter’s command and looked inside myself. And you have just read what I saw there.