ROCHELLE STEINER: Over the years it seems that some key aspects of Glenn Brown’s practice – particularly a type of abstract portraiture and science fiction imagery – have started to morph while simultaneously becoming more pronounced in their own right. On the one hand, there are paintings such as Filth 2003 and Dark Star 2003 that draw on the history of portraiture, but are presented with the most surreal approach, and on the other hand the strange, abstract, often truncated imagery resembling heads, feet and even planets, such as Deep Throat 2007 and It’s a Curse, It’s a Burden 2001. It appears that these poles of his work, which are of course intrinsically linked, are moving into their own orbits.

Glenn Brown

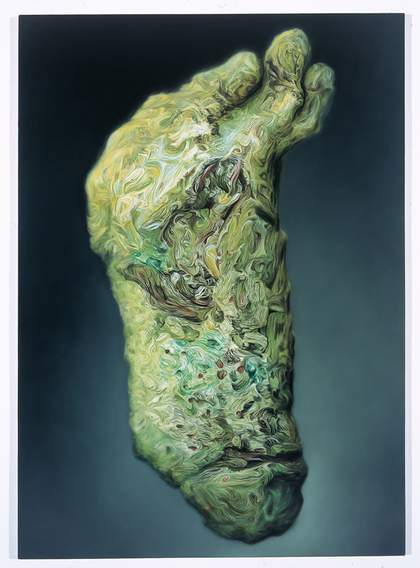

It’s a Curse, It’s a Burden 2001

Oil on panel

105 x 75 cm

© Glenn Brown

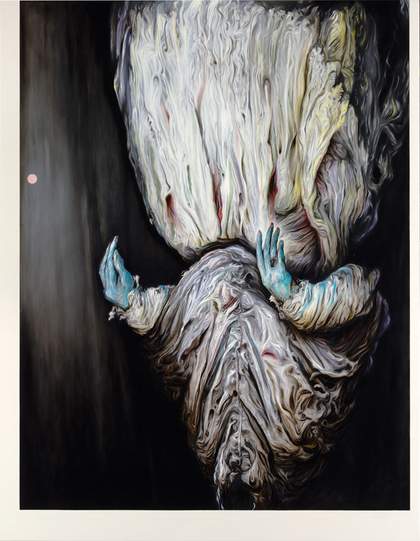

Glenn Brown

Filth 2004

Oil on panel

113 x 94 cm

© Glenn Brown

ALISON GINGERAS: While I certainly would not disagree with your identification of these two, albeit entwined, strands in Glenn’s art, I think it is worth pinpointing something that defines and drives his work, something that, for me, distinguishes him from his contemporaries, which is his unabashed love affair with paint and painting. This passion for paint runs throughout all of the different subject matters, forms and methods that make up his practice. Whether it is a sci-fi landscape, an abstract body part work or, to make a short cut, an appropriation of a more readily identifiable art historical image, he always engages in a meticulous, obsessive process. Not only does he make technically stunning paintings that self-referentially deal with the historical baggage of the medium, he seems to relish the application of paint itself. His use of trompe l’oeil to mimic expressionistic brushstrokes but on the flatest of surfaces is, at least to me, his perverse way to extol his love for paint. His romance with paint and painters is so multi-levelled.Even an artist such as John Currin (who is possibly his closest formal and conceptual compadre) does not engage painting on so many levels.

ROCHELLE STEINER: I agree that Glenn is what you could call a painter’s painter, and much has been written about his love of painting and his self-proclaimed position as a painter rather than an artist. What I find revealing for someone so clearly in love with painting and invested in exploring the medium on all the levels you outline, is his equally prevalent, though perhaps more latent, relationship to photography and appropriation strategies. I can’t dismiss the fact that his references are not actual paintings, but photographs – and usually bad reproductions at that – of iconic paintings, many of which he hasn’t seen in person. I find his approach to painting somewhat indirect: he seems to love the idea of painting as much as – if not more than – the paint itself. I think Glenn’s approach is more conceptually linked to appropriation than Currin’s, although of course Currin has also relied on photographic source imagery.

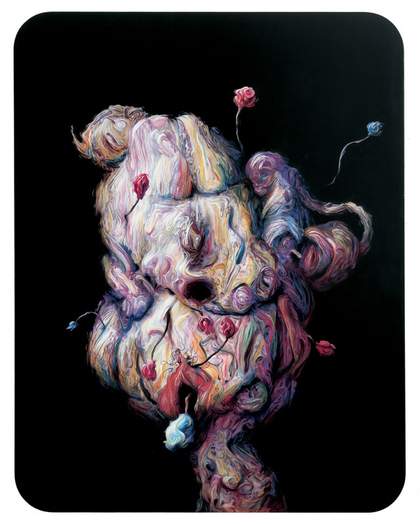

Glenn Brown

Nausea 2008

Oil on panel

120 x 155 cm

© Glenn Brown

Glenn Brown

Detail of Nausea 2008

Oil on panel

120 x 155 cm

© Glenn Brown

ALISON GINGERAS: Yes. He definitely has the appropriationist strand in his DNA. It is interesting because he uses the appropriationist method as a starting point as you have suggested, such as working first from a bad catalogue reproduction of a Rembrandt or an Auerbach in which the camera completely distorts the colour palette, after which he seeks to inject his own authorship by seizing upon the discrepancies between the original and the reproduced image. For example, he often runs with the distortion of colour in a reproduction in order to indulge his copy in a palette of completely sick greens or browns. This tension between appropriation and distortion is where the level of conceptual and visual sophistication gets interesting for me. It is as if the first step is appropriation, but once he starts to really work on the painting, his formal and conceptual process introduces elements of originality or rupture in the act of copying the picture. Also, Glenn appears to have moved away from the critical aura surrounding appropriation art of the late 1970s and early 1980s in the way his work does not seem born out of a desire to comment politically upon or critique his subject matter (as was the case with first generation “pictures” artists such as Sherrie Levine or Cindy Sherman in the late 1970s). Instead, his motivation to appropriation seems more born out of lovingly fetishising his sources, whether obscure or iconic art works. He carries the appropriationist torch to a next level – further blurring the cultural status of original and copy, traditional methods and avant-garde gestures.

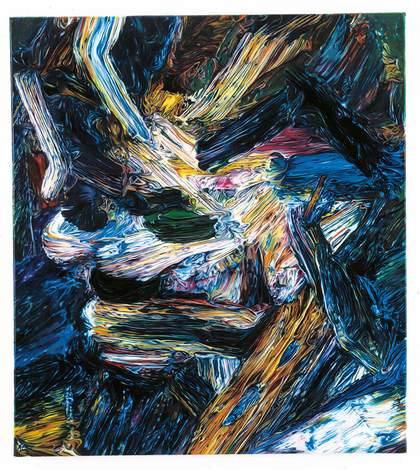

Glenn Brown

Breaking God’s Heart 1999

Oil on wood

75.4 x 65 cm

© Glenn Brown

ROCHELLE STEINER: Glenn can definitely be counted as a second generation appropriationist, the twist being his interest not in establishing truth to or a critique of originality, but rather his sense that sources are available for quotation, decontextualising, stretching, reorientating, morphing and re-situating in his own work. This is as likely to happen with a Fragonard painting (his The End of the 20th Century, 1996) as a science fiction illustration (Dark Angel [painting for Ian Curtis] after Chris Foss, 2002). The same is true of his titles sampled from songs, such as The Smiths’ lyrics that became This is the last song I will ever sing. No, I’ve changed my mind again. Goodnight and thank you, or films including Saturday Night Fever and The Sound of Music, also titles of Glenn’s paintings. It seems that his strategy runs closer to sampling than appropriation in that his goal is not proximity to source material, but rather mixing sources as a DJ does to create combinations of words, images and even types of brushstrokes.

Glenn Brown

Dark Angel (for Ian Curtis) after Chris Foss 2002

Oil on canvas

223 x 341 cm

© Glenn Brown

Glenn Brown

The End of the 20th Century 1996

Oil on canvas, mounted on board

75 x 57.5 cm

© Glenn Brown

ALISON GINGERAS: Although when he does sample these song lyrics, the choice of specific sources tends to create an opposite effect to the intellectual distinction associated with the act of appropriation or sampling. Almost all of Glenn’s titles conjure a certain dark and poetic romanticism (especially when he lifts lyrics from The Smiths or Joy Division) that tempers the overtly conceptual nature of the work by bathing it with heartfelt emotion associated with those music choices. This ability to produce art that is culturally both “hot” and “cold” is unique to my mind. Would you agree?

ROCHELLE STEINER: I think you are right that there are two emotional poles within his work – what you have identified as the hot and cold. Perhaps this is linked to what feels to me like simultaneous yet oppositional effects of his art on viewers – a competing “push” and “pull”. Glenn’s work draws us in with his absolutely gorgeous painting and pop references, while confounding us with what appear to be discrepancies or gaps between images and titles, portraits and science fiction references, or art history and popular culture focal points. The references themselves, let alone the relationships between them, are not always apparent, leaving viewers puzzling over how elements add up in the artist’s mind. As Glenn has said, the connections between the paintings and their titles are not always obvious; more often than not they are enigmatic, and are meant to create a sense of disharmony or misalignment.

Glenn Brown

International Velvet 2004

Oil on panel

121.5 x 145.5 cm

© Glenn Brown

Glenn Brown

Detail of International Velvet 2004

Oil on panel

121.5 x 145.5 cm

© Glenn Brown

ALISON GINGERAS: What do you make of the sculptural component of Glenn’s practice? It is another piece of the puzzle that is often glossed over and does not exactly fit into the same conceptual processes as the two-dimensional paintings.

ROCHELLE STEINER: It’s a very compelling and, I would agree, much overlooked aspect of his art. It is my understanding that for Glenn painting and sculpture are on equal terrain, and I have come to see the sculpture as one of the key connective tissues – formally and conceptually – within his career. The Andromeda Strain 2000, for example, resembles a three-dimensional head from one of his paintings (consider, for instance, Breaking God’s Heart, 1999); Petrushka 2000 implies a figurative approach – head and body elongated and rendered in three dimensions; and The Shepherdess (2000), in part because of its large scale, is like a planet or meteorite. When I curated an exhibition of Glenn’s work at the Serpentine Gallery, Glenn and I positioned The Shepherdess near The Loves of Shepherds (after ‘Doublestar’ by Tony Roberts) 2000, one of his quintessential sci-fi paintings. The opportunity to view them in proximity gave a sense of deep interrelatedness between the two and three-dimensional work. In fact, all of the sculptures in that show were installed among the paintings, and the sculptures brought the intensity of Glenn’s brushstrokes to life – there they were, thickly rendered, standing upright and defying gravity. While we have discussed his appropriation of existing imagery, and ruptures from the original antecedents, we haven’t talked much about his process and how he gets there technically. He has certainly utilised photographic sources – including images found in old catalogues, photo-copies he makes and off-colour postcard reproductions – but increasingly he creates digital drawings on the computer as a preparatory stage. This gives him the tools to zero in on some visual aspects, or stretch and augment others – all the while further decontextualising the object of his inspiration from its source. What do you make of the role of digital technology in painting today?

Glenn Brown

This is the last song I will ever sing. No, I’ve changed my mind again. Goodnight and thank you 1993

Oil on canvas

53 x 47 cm

© Glenn Brown

Glenn Brown

The Andromeda Strain 2000

Oil paint on acrylic over plaster, vitrine

35 x 32 x 30 cm

Collection Rudolf and Ute Scharpff

© Glenn Brown

ALISON GINGERAS: I suppose it is inevitable that any societal phenomenon (such as the omnipresence of the computer in our daily lives) eventually finds its way into how artists both think about and make their art. And as you point out with regards to Glenn, the computer has become an important, if not unavoidable, tool in his technical process. His use of this tool again points to the way he crafts his artistic alchemy – a careful concoction of push and pull. He can take advantage of new technologies without sacrificing the purposefully traditional slant of his work, or even his anachronistic fetishisation of paint itself. Many artists, and in particular other painters, have seized on these technological possibilities. Jeff Koons uses computers to design entirely his densely layered imagery before the paintings are then executed by hand, while others utilise them either to appropriate source material from the web or generate “original” imagery. Wade Guyton, Kelley Walker, Rudolf Stingel, Kristin Baker and Miltos Manetas are all what you might call painters of modern life – they carry on the heritage of Pop artists who quickly adopted new photo-mechanical processes of the early 1960s (eg silk-screening and solvent transfers) both as method and influential on the subject matter of their work. I am curious if the ubiquity of the computer in the artist’s studio hasn’t caused a Luddite backlash, at least on a minor scale. Unlike the original Luddites who were destroying automatic weaving looms, I don’t mean to suggest that artists are throwing their Apple laptops out of the window… but I have noticed a small trend in which painters who are working en plein air or painting from life are applauded for shunning newfangled processes in their art. Two salient examples come to mind. First, David Hockney, who returned to England after years working in Los Angeles (where, among other things, he was lauded for his pioneering use of photographic and other technologies in his work) and is now devoted to making landscape paintings outdoors in his native Yorkshire. To quote from Tate’s own press department, Hockney’s return to this antiquated en plein air technique is cause for celebration: “Loading his pickup truck with easels, canvases and paints, Hockney drives to his chosen destination and sets up his tools. Then he sits for a couple of hours looking at the landscape, absorbing the view, before picking up a paintbrush. This quiet but intent observation is followed by feverish activity to capture the essence of what he sees. Hockney conveys the land and light in electric colour, bringing to the canvases his love of place, freshly observed and infused by decades of experience and his memories.” Likewise, Elizabeth Peyton was praised recently in the New York Times review of her career survey at the NewMuseum. Critic Roberta Smith credited the artist with shifting away from her earlier methods of painting from found images and personal photographs of her sitters to working from live models and situations. As Smith writes, when Peyton is “painting more from life than from photographs her work deepens”. Perhaps like with any other form of cultural creation, values and tastes are ever shifting. Given the pervasiveness of the computer in the artist’s studio, the trend in contemporary painting may perhaps be shifting backwards to more authentic (read: unmediated) methods as illustrated by these two examples. One of the reasons I love Glenn’s work is because it questions these (facile) notions of authenticity with regards to method, subject matter and emotional pitch.