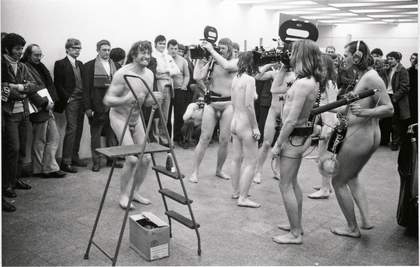

Balthasar Burkhard<

Otto Muehl, Herbert Stumpfl, Romilla Doll and Mica Most performing the Manopsychotic Ballet action at the Kölnischer Kunstverein 1970

Photo: Balthasar Burkhard

Courtesy Kölnischer Kunstverein © Otto Muehl

The last time I talked with the late curator and art historian Harald Szeemann – we met by chance at the train station in Zurich – I asked him why he hadn’t included happenings and performances more prominently in the seminal Documenta 5 that he curated in 1972. He replied that he originally intended to give them much more space and even made a dry run to test their potential, namely ‘Happening & Fluxus’. He organised this show at the Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne, in winter 1970, after leaving the Kunsthalle Bern. However, the result, he explained, turned out to be a disaster – performance simply did not fit into an exhibition.

How would art history have developed, one might ask in retrospect, if ‘Happening & Fluxus’ had not been a failure? What if the public had liked it and the politicians and collectors supported it? What would be different in today’s realm of art if the exhibition had paved the way for protagonists such as Otto Muehl and Allan Kaprow, instead of ousting them from the canon of art history during the 1970s and 1980s? Would we have another kind of art if Documenta 5 had been focused on happenings and performance, carrying on the playful impetus of the 1960s, instead of squeezing art back behind the walls of the museum?

The photographs of a group of naked performers surrounded by a rather indifferent audience strike me as crucial documents in this debate. They were unearthed in the archives of the Kölnischer Kunstverein and announced a retrospective exhibition about ‘Happening & Fluxus’, curated by Marcel Odenbach in 2007. Taken by the Swiss artist Balthasar Burkhard, it documents Otto Muehl’s Manopsychotic Ballet (Part 2), staged on the afternoon of 8 November 1970 by two male and two female performers, namely Otto Muehl, Herbert Stumpfl, Romilla Doll and Mica Most, with Charlotte Moorman playing the cello. Obviously, the event was produced both for a live audience and the camera. Two cameramen and two sound engineers are directed towards Muehl. Like Moorman, the members of the film team are naked. They are both the observers and the observed, distanced witnesses and exposed performers.

The Manopsychotic Ballet was the last important action by Muehl before he retired from the art world after a decade of painting and performance and focused on his commune as an alternative way of living. It marked the end of a very prolific phase of actions that followed the legendary Art and Revolution action by the Viennese Actionists in Vienna in 1968. As a result of this performance, Muehl and Günter Brus were prosecuted and could no longer exhibit publicly in Austria. Muehl was successful with performances in Germany, such as Oh Sensibility, Shit Head and The Wanton Woden. His actions, either in private apartments or public exhibition spaces, featured naked protagonists who were mimicking acts of sexual violence, sadism, masochism and the devouring of animals such as pigs and hens. The atmosphere was grotesque, cabaret-like, and several performances provoked scandals, such as Oh Tannenbaum in Braunschweig in December 1969, where a butcher slaughtered a pig. In the case of ‘Happening & Fluxus’, the city authorities of Cologne put pressure on the Kunstverein after right-wing politicians and representatives of the Catholic Church protested about human defecation and the slaughtering of animals during the actions of Muehl and Hermann Nitsch. The director eventually removed the exhibitions of both artists.

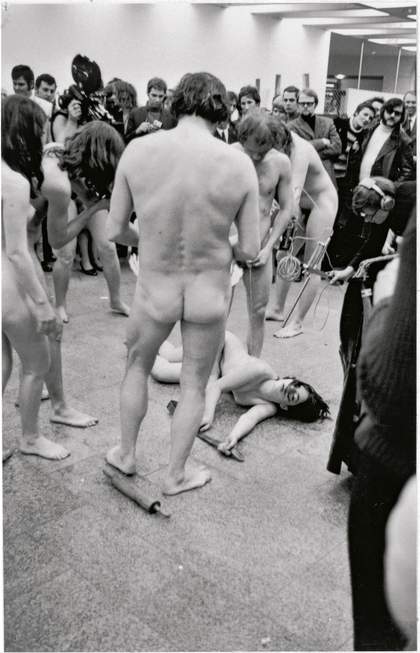

Looking at the photographs today, one might wonder why the public was so shocked. However, there are other pictures by Burkhard and a 16 mm film by Jörg Siebert that show more explicit details. The action begins with a ritual dance of the performers, who caress each other’s genitals and mimic sexual intercourse. Muehl then extracts a tampon from the vagina of one of the female performers, presents it to the audience and carries it triumphantly between his teeth. Later, he inserts a rolling pin into her vagina. He whips her with a belt before being whipped himself by her and the others. There is a scene where a cameraman pretends to rape a female performer by inserting the lens of a camera into the vagina. In another scene the two male performers urinate on the body of one of the females. Towards the end, a live chicken is introduced into the proceedings. It remains unclear if it is actually slaughtered on stage, but the performers tear the dead bird to pieces and act as if they are devouring it. In the closing scene, Muehl defecates towards the lens of the camera. This sequence seems to be shot separately, not during the performance.

Balthasar Burkhard

Otto Muehl, Herbert Stumpfl, Romilla Doll and Mica Most performing the Manopsychotic Ballet action at the Kölnischer Kunstverein 1970

Photo: Balthasar Burkhard

Courtesy Kölnischer Kunstverein © Otto Muehl

Aside from the perceived controversial nature of the performance, one cannot help but identify the Manopsychotic Ballet with the social and political events of 1968. The confrontation between the group of vulnerable naked young people exposing themselves to an anonymous crowd immediately recalls issues such as student protests, sexual revolution and the clash of the generations. The iconic photograph of Kommune 1 in Berlin comes to mind, which shows the naked members of the group standing against the wall, ready for inspection by the police. Some interpreters would probably see Manopsychotic Ballet as a symbolic re-enactment of the paternalistic structure of the older generation, based both on violence in the private sphere and the passive tolerance of the violence by the State. Political interpretations are particularly popular among art historians, because they support one of the founding myths of contemporary art – namely its birth out of the spirit of rebellion. One is pleased to hear it, because it continues the cherished story of the avant-garde’s triumph over bourgeois norms in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

However, why was the Manopsychotic Ballet forgotten for almost 40 years, why are there no traces of this work in art books and why did Szeemann think it did not fit into Documenta 5? The answer is that the art world – the community of cutting-edge artists, critics, curators and dealers – was afraid that it would undermine the tacit agreement that it and the rebellious students stood on the same side in those turbulent years. The work had to remain invisible because it risked revealing that the art world was not unanimous and coherent at that time, but marked by internal conflicts. What if the naked performers were not really protesting against the State, against the moral regime of society, against their parents’ generation, but rather against their audience? What if their enemy was not the reactionary politicians beyond the walls of the museum, but rather the seemingly progressive organisers of the event and the vivid, young and open-minded audience, ready to cope with every new artistic production and absorb every new provocation, those young people we see standing in the room, arms crossed, tolerant and sceptical at the same time – in other words, us?

Balthasar Burkhard

Otto Muehl, Herbert Stumpfl, Romilla Doll and Mica Most performing the Manopsychotic Ballet action at the Kölnischer Kunstverein 1970

Photo: Balthasar Burkhard

Courtesy Kölnischer Kunstverein © Otto Muehl

The identification of the events of 1968 with neo-avant-garde art that prevails today is too simple. We tend to overlook the internal conflict within the realm of art that took place during the 1960s and can be traced in the fact that during that decade the earlier notion of “artist’s world” was replaced by the now common term art world. In fact, the artists lost their central role towards the end of the decade. The cascade of “isms” and the vivid debate about the definition of art that went on in journals and on discussion panels are not only the result of the historicist reference of 1960s art to the classic avant-garde. They are also symptomatic of a struggle about the control of the mediation of art, about the authority to validate art, to define its meaning. With a rapidly growing international public, with an expanding art market and with the enormous appetite of collectors and museums for ever-new works of art, the mediation of art became a valuable resource. Artists, critics and curators were struggling to control this resource. And the variety of names that were coined to define the different movements is in some way comparable with the claims made by gold-diggers a century earlier. By the end of the 1960s, the winner of this struggle was clear, namely the museums. Documenta 5 is emblematic of this shift of power, because it symbolises the rappel à l’ordre of the early 1970s, in other words, the domestication of an extraordinarily vital and complex phase in the history of art during the 1960s. The exhibition, and the colossal catalogue that went with it, stood for the triumph of the museum over the artist. Since Documenta 5, curators, not artists or critics, decide the contents of exhibitions, their themes and trends. Curators such as Szeemann became the key figures in the consolidated art world, and the critics’ voice, as well as that of the artists, lost much of its earlier influence.

If one looks closer at the oeuvre of Muehl, one can see that he was very critical of the art of his time. In the programme of his Institut für Manopsychotik, he distances himself from what he calls “representative” art, meaning art that does not really interfere with life, and he considers “happenings as thoroughly bourgeois art, just art”. Seen from this perspective, the action can be read as persiflage of a happening, the performers aping performance art and mimicking the closed-circuit structure of ephemeral media by including a naked film team as part of the performance. While the action Art and Revolution two years earlier was a test to find out how tolerant the student activists were towards art that was not ready to be instrumentalised, but who insisted on its autonomy – in the end the student activists distanced themselves from the artists – in the Manopsychotic Ballet, I would argue, was a test of the curators. The result of this test was not only the censorship of Muehl by the authorities of the Kunstverein, but, more importantly, Szeemann’s decision to exclude this kind of art from Documenta 5 altogether, and produce an exhibition that respected the limits of the museum. After that, there was no way for Muehl to gain access to the mainstream, to the important exhibitions and collections that set the trend of the 1970s and 1980s. Whereas Kaprow, to give another prominent example, retreated to his academic teaching and to small-scale performance almost without an audience, Muehl retreated to his commune, the action-analytical organisation that temporarily had more than 600 members.

Other artists, however, fitted neatly into the new regime and entered the mainstream. The most visible artist present in Documentas 5, 6 and 7 was Joseph Beuys. In retrospect, iconic works such as the print entitled La Rivolutione siamo noi 1971, where the artist is represented marching towards the camera in an obviously revolutionary pose, have forged the myth of the political roots of contemporary art. The image is still popular in the realm of art because everyone likes to identify with it and because it suggests that the mysterious “noi” means “us”; in other words, the art world and art per se is revolutionary.However, Beuys never addressed the authoritarian structure of the art world as such. Like other authors of political art, such as Hans Haacke or Thomas Hirschhorn, his work is cherished by the institutions precisely because it implies that the art world is beyond the need of political analysis. Beuys’s gesture was welcome because it suggested that art could act on society, but not the other way round. In consequence, Beuys, during the 1970s, was sometimes criticised by fellow artists of being “unpolitical” – a judgment that implicitly recalled Thomas Mann’s Observation of an Unpolitical Man, a legitimisation of Germany’s role in the First World War that became the synonym of cultural opportunism.

In fact, Beuys never boycotted an exhibition – unlike Robert Smithson. Who remembers today that Smithson was among the few who boycotted Documenta 5, precisely to protest against the inherent, yet repressed authoritarian structure within the art world that sought control over the artists. In his view, Szeemann acted like a warden of the prison, putting artists in little white cubes. Smithson’s text “Cultural Confinement” appeared in the catalogue of Documenta 5 and opens with the words: “Cultural confinement takes place when a curator imposes his own limits on an art exhibition, rather than asking an artist to set his limits… Some artists imagine they’ve got a hold on this apparatus, which in fact has got a hold of them.” The inclusion of his statement made clear that the institution of the museum was powerful enough to absorb everything, even explicit critique. Szeemann continued to show the work of Muehl in his exhibitions, yet always framed as an outsider, beyond the artistic mainstream. Documenta 5 is so important because it marks the moment when curators or, more generally speaking, the institution of the museum took over control and the authority to decide about the inclusion, or exclusion, of artists into the canon of contemporary art.

Muehl, I would argue, produced two mirror images, one of the repressive structures of European post-war society, the other of the authoritarian structure of the emerging art world. Thus, he put the viewers in an ambivalent, confusing situation. Labelling his action a “ballet”, he implicitly stated that the relationship between the artists and their audience was still deeply rooted in the entertainment structure of the nineteenth century. Deconstructing the hidden erotic meaning of the ballet by aping pornographic scenes, he made them into voyeurs. Of course, it belongs to the irony of art history that Muehl’s commune itself also became institutionalised after a while and that he, in the end, reproduced the very authoritarian structures he initially tried to overcome. But the art historical importance of the Manopsychotic Ballet, as I see it, lies in its capacity to make visible the usually hidden boundaries of the cultural realm. It makes clear that the art world had turned into an institution that, even if its protagonists did not intend to do so, developed its own exclusive and authoritarian structures. The State always knew exactly how to react to the actions of Muehl and install its jurisdiction. But unlike the State, the art world could not really cope with his art. The action put the dominant institution of the art world, the museum, embodied at that time by Szeemann, in a position where it had to exclude his work to protect its own authority. In the end, Muehl was simply struggling for the autonomy of his art. Yet this is more than the art world could – and still can – tolerate.