Since the late 1960s, artists using the time-based media of film and video have continually pursued two kinds of spatial enquiry – investigating the space in the image, and complicating the space of its projection. Attentive to the machinery of their medium, they were often as interested in how a camera or lens recorded the space before it as in the content of what it recorded. They consistently refused to make use of the darkened cinematic space with its rows of seats in which we usually view film, or the half-lit sofa-plus-monitor domestic space in which we normally watch TV and video. Films and videos were installed instead in galleries and, once installed, the projector acted as a kind of hinge between two spaces (the image’s and the projection’s).

Video offered the possibility that the hinge could be snapped shut – the space shown in the image could be identical to that occupied by the projection. A camera set up in a room recorded whatever passed in front of it, simultaneously playing back the image on a monitor or projecting it on to a screen in the room. Filmmakers could also emphasise the present tense in which their work was encountered by dramatising the space between projector and screen. They would project on to screens from the floor knowing their audiences would interrupt the beam of light. Though the image on celluloid was inevitably imprinted before the event, the image on the screen was contingent on whatever occurred at the specific time of the projection.

Early artists’ film and video work tended to be produced in tight-knit artists’ communities in a handful of Western cities, and was shown to small audiences in individual screenings or solo shows, away from the pressures of other works. It occupied a privileged position by virtue of its newness and impermanence. Now, video and film no longer have any kind of oppositional cachet. The work tends to be shown in large group exhibitions, so artists have to consider the spatial and temporal competition of other displays vying for the viewer’s attention.

But perhaps the biggest difference is the geographical space now occupied by film and video art. Video and film are employed by artists living and working all over the globe. Because cameras are so mobile, video (and to a slightly lesser extent, film) can be made anywhere, and because finished rolls of film, tapes and DVDs can be shipped so easily, the work can be shown anywhere. Film and video art is ubiquitous in biennales from Venice and Istanbul to Liverpool.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that contemporary film and video works feature spaces from all over the world. In Time Zones there are images of Albania, China, Germany, Indonesia, Israel, Japan and Mexico. These are the countries where the artists come from, and where they travel to make their art. North America is conspicuous by its absence, while only one piece has been produced within the EU. Few of the artists, however, tell stories about these places – they are more interested in showing how time is differently experienced in them. Clearly, both makers and curators are wary of exoticism – of the danger of portraying non-Western locations as strange and wonderful, possibly more in touch with a relaxed, authentic temporality unaffected by Western urban bustle. Instead, the curators aim to display works pointing to the many different temporalities competing in any one location.

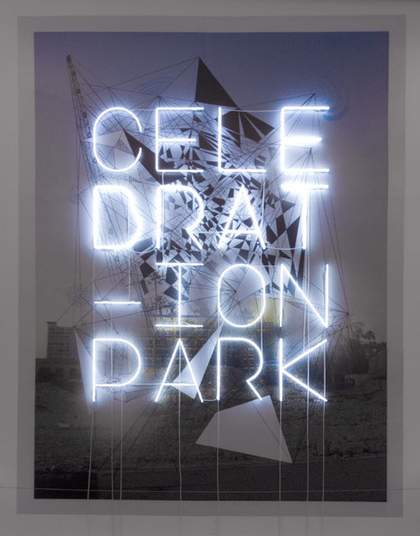

Fiona Tan

Saint Sebastian 2001

Courtesy of the artist and Frith Street Gallery.

If it is crucial for artists to show in their images the spaces and times of the world, surely it’s still important – in fact, more so than ever – for them to consider the specificity of the exhibition space and time. The white cube or black box of the museum could certainly be emblematic of the homogenised spatiality and temporality of globalised capitalism. It is this homogeneity that the work seeks to contest. In the past couple of years, artists such as Pierre Huyghe, aware of the problem, have made films taking specific architectural set-ups into account. Time Zones will provide an opportunity to compare how artists interested in spaces and times treat installation: are we made aware of the architecture of Herzog and de Meuron’s galleries, or persuaded to ignore it? Does the time shown in the film correspond with the time of day when we watch it? Does daylight permeate the viewing space, or are windows blacked out? Can we see where and how projectors are located, or are they concealed? How are monitors and screens deployed within the space?

There is a third kind of space that is also crucial: the one occupied by the camera during the filming. Some films are made using telephoto lenses and cameras which appear not to have been noticed by the human protagonists – Fiona Tan’s Saint Sebastian 2001, for instance. Some are shot with a less than steady camera – the subjects of Fikret Atay’s Rebels of the Dance 2002 are awkwardly aware of its presence. Other artists in the exhibition position a camera in a fixed spot, letting it film without moving it. Jeroen de Rijke and Willem de Rooij’s Untitled 2001 returns us to the space of painting. The camera looks down on to a graveyard and across to the buildings on the horizon; without feeling implicated in this space, we scan the image as if from a distance.

There is always a political dimension to these points of view: concealed cameras might be termed voyeuristic, while those surveying from above may be deemed all-powerful. In this respect, Anri Sala’s Blindfold 2002 is particularly interesting. It is a double-screen video installation, with each screen showing an empty billboard filmed by a camera positioned at a fixed point on the street below, right in the thick of things. Unlike surveillance cameras, this one looks up. In the image to the right, the billboard occupies the upper left corner, and to its side we can see buildings and a road along which pass various people, cars and buses. During the course of the fifteen-minute projection, the billboard catches the reflection of the sun, which must have been behind the camera. As it does, it glows, and the glare consumes portions of the image around its borders. Now, it could seem that Sala is contrasting natural and urban time – the constant temporality of the sun with the quirky temporality of the Albanian city, in which there are as many signs of movement as of stasis. Or perhaps he is comparing the slow time of both. Maybe the image stages a kind of competition between two traditional film-makers’ subjects – timeless natural subjects and social, historical subject matter. Do we attend more to the natural or the social?

However, we should recall that this is not a film of a sunset, an eclipse, or any other natural phenomenon, but of a reflection, and it’s a crucial difference. First, the glint alerts us as much to the sun as to the object that reflects it – an empty advertising hoarding, a truly modern object, one suggestive of commerce and propaganda, but here of its absence and possible imminence. The glint of sunlight also directs our attention to the street. This isn’t just because the white-out makes us look away from the top right to the left of the image. It’s because the reflected light demonstrates that the camera stood in a particular position. For the reflection appears in only one place; had the camera looked at the same billboard from another angle a few metres to the left or right, it would not have been there. After all, in the video the people who pass by aren’t distracted by the sun at all.

Sala therefore reminds us that what we see through a camera depends on where we look from and when we look at it. This is in itself a critique of many of the assumptions of traditional documentary with its claims to objectivity. But it is also a critique of the abstract temporality and spatiality of earlier video and film art, as his work insists that the camera is recording not just at a particular time in the day, but at a specific time in history. In the gallery space, the two beams in each image – the one from the sun to the billboard, the other from the billboard to the camera – might be echoed by the two beams coming from the two projectors. In this way, we become aware of the time and space of our encounter every bit as much as in the image.