“I’ve got nothing to express! I simply search for images and I invent, I invent…only the image counts, the inexplicable and mysterious image, because all is mystery in our life.” – René Magritte, interview with Maurice Bots (1951)

Appropriation is a form of cultural plundering that is prominent in much contemporary art today – but it also pervades the work of René Magritte. Many of the themes and motifs in his art derive from writers such as the Surrealist anti-hero Lautréamont, Lewis Carroll and Edgar Allan Poe, and from the work of other artists such as Derain, Picasso and de Chirico, as well as from the regular recycling of elements of his own paintings.

Still from Louis Feuillade’s Fantômas (1913)

Courtesy Kobal Collection, London

Magritte borrows, too, from popular sources such as comic books and pulp fiction – from the detective stories of Nick Carter and Nat Pinkerton, and particularly from the epic Fantômas series of Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain, published when Europe was on the brink of the First World War. And his titles, the bulk of which were carefully chosen by writer friends such as Paul Nougé and Louis Scutenaire for their poetic effect rather than to explain the image, in many cases come from literary and other sources, as with The Imp of the Perverse (1927) and The Domain of Arnheim (1938), both taken directly from Poe, or The Interpretation of Dreams (1930), borrowed from Freud.

With Magritte, appropriation is almost never straightforward visual duplication. His reworking of the masked criminal on the cover of Fantômas for The Flame Rekindled 1943 is a rare example of such a close copy, but more usually he combines visual quotations with conceptual and linguistic elements, together with personal references, to produce a far more complex mixture.

Having trained at the Academy of Beaux-Arts in Brussels during the First World War, he experimented with variants of Futurism and late Cubism. But around 1923 he experienced an epiphany on encountering de Chirico’s The Song of Love 1914, with its enigmatic juxtaposition of classical bust and red rubber glove, and was immediately captivated by its “triumphant poetry” and sense of mystery. By 1925–6, under the spell of de Chirico and the collage style of Ernst, Magritte suddenly began to develop a more personal visual vocabulary that explored his own concerns, with particular reference to the traumatic suicide by drowning of his mother in the river Sambre in 1912. Only thirteen at the time, he claimed to have seen the recovered corpse, head shrouded in the dressing gown she had been wearing. He would also have followed the adventures of Fantômas as the successive volumes with their lurid covers appeared in bookshops between 1911 and 1913. The sinister black-cowled figure of the master criminal – described as “the silhouette of death” – is appropriated in paintings such as The Man from the Sea 1927, while The Menaced Assassin 1927, one of his most celebrated works, is modelled on a scene from Feuillade’s film version of the novels, and depicts the apparent murderer standing casually beside the naked and bloody corpse of his victim, while two bowler-hatted detectives lurk on either side of a doorway. There are perhaps other, more veiled references to the books in other works, such as the detached hand in One-night Museum 1927, recalling the gory hand clutching at a roulette wheel on the cover of the volume entitled The Severed Hand.

Page from FE Bilz's The Natural Method of Healing, Vol 2 (1898)

Courtesy Wellcome Collection

René Magritte

Man with a Newspaper (1928)

Tate

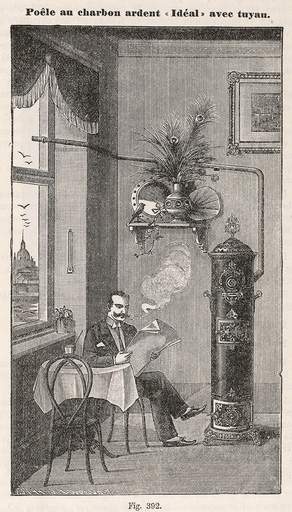

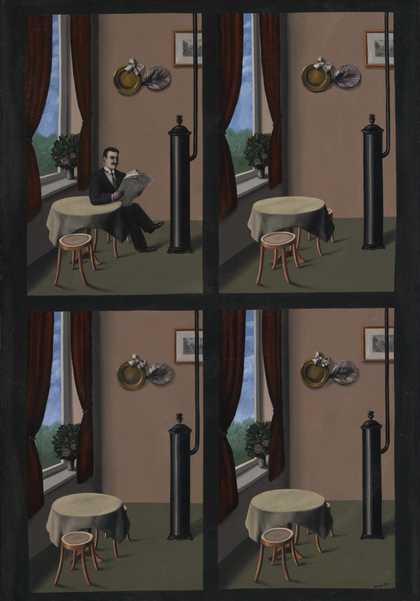

Man with a Newspaper 1928 takes its theme from Derain’s Portrait of a Man with a Newspaper (Chevalier X) 1914, a portrait of a seated man reading a newspaper with a curtain on his left. Magritte inserts these elements in a domestic interior taken from Dr F.E. Bilz’s The Natural Method of Healing (1898), a popular health compendium first published in Germany, to create a rather cinematic sequence in which we first see a man reading beside a window, followed by three further views of the now deserted room. Despite being painted shortly after the death of his father in August 1928, the style and fashions of the image clearly evoke the pre-war era, perhaps recalling that generation of men who went to war and never returned.

But what is even more curious is that the disappearing man should have reappeared a couple of years later, albeit only temporarily, in another painting from the Tate collection – The Annunciation 1930 – one of a number of Magritte’s images referring to Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead 1880, a sepulchral island set in a morose stretch of dark water. An X-ray of the painting reveals that it originally also featured a seated man reading a newspaper among a group of figure-like, totemic forms. He was subsequently painted over, concealed now by a bush and enduring only as a ghostly absence in an eerily expectant landscape.

The American Surrealist poet Patrick Waldberg notes Magritte’s “tendency to hypochondria”, as well as his pessimism, making it likely that he often pored over his volumes of Bilz, and they are probably one of the sources of his 1935 gouache La gâcheuse (translated as The Spoiler), a macabre figure that combines the naked body of a woman with a skull-like head. Precisely such a figure is to be found in the anatomical illustrations at the end of Bilz’s manual, where the face can be folded back to reveal the skull and the body folded over to expose the internal organs. What is particularly disturbing about Magritte’s image is that a layer of skin hovers somewhat uneasily between a head and a skull, suggesting the living dead of horror movies. On one level this evokes the long tradition in Western art of similarly representing women in memento mori and vanitas paintings, reminders of our mortality and the transience of beauty, as well as recalling Symbolist imagery linking fears around female sexuality with death. We could also add nineteenth-century warnings of the dangers of syphilis, one of the conditions featured by Bilz, so that the painting carries a whole range of cultural anxieties focused on the female body. He also painted a number of plaster death masks, of Napoleon and Pascal, as well as of a female figure recalling the well-known L’inconnue de la Seine (the unknown woman of the Seine), the death mask of a young girl with an enigmatic smile, pulled drowned from the river. For Magritte, this would clearly have personal connotations, while also referring to the romanticisation of female suicide in the practice of many artists hanging such a death mask in their studios.

Photographs and postcards also provided the source of a number of Magritte’s images, particularly as a model for the human body, a striking example of which is his portrait of the gallerist and occasional poet E.L.T. Mesens. The two men met in 1920 and had a lifelong and at times difficult relationship marked by regular disputes, usually involving Mesens’s role as his dealer. When the gallery of the artist’s Paris dealer Camille Goemans collapsed in 1930, Mesens came to the rescue, buying up a batch of eleven works – a feat he was to trump in 1932 when he bought around 150, preventing their dispersal at auction at giveaway prices. Magritte’s portrait, conceived in the form of a spoof film poster, is a somewhat barbed tribute that commemorates how Mesens “rose to the occasion”. A photo of the dealer shows him apparently aiming a gun. In the painting he appears immaculately dressed, but in the role of a conjurer holding some strange wooden device operated by string, and bearing the bloody head of a Pomeranian, Magritte’s favourite breed of dog. The artist often jokes in letters about the canon bibital (private “gun”), and around this time addressed a postcard to “Monsieur ELT Mesens (manufacturer of marshmallow revolvers and whistling hens)”, suggesting precisely the opposite of a man able to “rise to the occasion”.

Diana Brinton-Lee, Salvador Dalí (in diving suit), Rupert Lee, Paul Éluard, Musch Éluard, ELT Mesens at the International Surrealist Exhibition in London (1936)

© Tate Archive

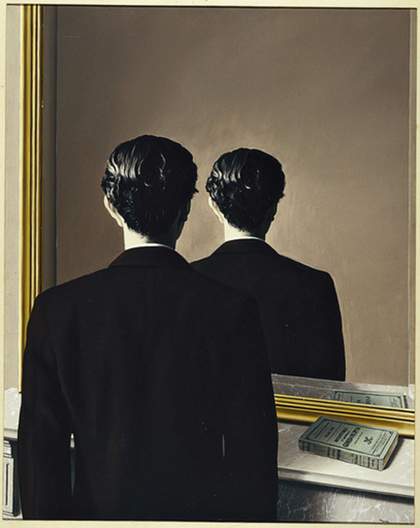

Mesens later played a pivotal role in introducing Magritte to an English audience at the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936, staged at the New Burlington Galleries in London, where despite a baffled response from English reviewers, he sold several works and came to the attention of the wealthy collector and writer Edward James. The following year James commissioned three canvases that he installed behind two-way mirrors in the Adam ballroom of his Wimpole Street home. The paintings appeared only when the lights behind the mirrors were illuminated, and were clearly suggestive of a kind of surreal looking-glass world, with Lewis Carroll then being regularly claimed as a precursor of Surrealism in England. The same year Magritte produced a striking portrait of James titled Not to be reproduced, in which the collector is viewed from behind staring into a mirror, but where, paradoxically, his reflection is also seen from behind.

René Magritte

Not to be Reproduced 1937

Oil on canvas

81.3 x 65 cm

Courtesy Museum Boymans-van-Beuningen, Rotterdam © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2011

In 1939 James made a further major purchase of three canvases and nine gouaches, including the important Time Transfixed 1938, which depicts a miniature steam engine erupting from a domestic fireplace. Both the fireplace and the gilded mirror above it figured in the earlier portrait of James, confirming that we are again in that same looking glass world. Magritte was familiar with Carroll’s writings, adapting motifs from Alice in Wonderland in a number of his works, and was surely struck by their appropriateness in the home of an English eccentric. Just as Alice leaps on to the fireplace and then passes through the mirror into Carroll’s looking-glass domain, the locomotive emerges like a visitor from another realm. The idea for the image, though, was initially developed in a short film scenario written by Magritte around 1936, so may have had some personal significance bearing in mind that the artist was born in the rue de la Station, at Lessines, in 1898. There is perhaps also a nod here to the melancholy of de Chirico, who featured distant steam engines in a number of works, where they evoke the early death of his railway engineer father. The severity of the black clock, like that of the locomotive, along with the brass candlesticks, the marble of the fireplace and the ominous void of the mirror all tend to lend a funereal air to the image, something even more evident in the original film scenario. Magritte proposed that the work be sited at the foot of the staircase leading up to the room where the earlier paintings were located, so that it would serve as a kind of magical threshold where guests would cross over into James’s looking-glass world.

Appropriation remained a tactic deployed in Magritte’s later work, as in Perspective: Manet’s Balcony (1949), a reworking of Manet’s celebrated balcony scene (itself borrowed from Goya), or Perspective: David’s Madame Récamier 1951, after David’s portrait, where in each case the original figures were replaced by coffins. Michel Foucault presciently observed that Magritte’s Balcony recalled “an open tomb”, suggesting a modern version of a “resurrection”. Magritte produced numerous versions of these and other of his best-known works as his reputation began to expand during the late 1950s – particularly in the United States. This playful reworking of the art of the past looks back to the sources of his own earliest creative impulses in his childhood trauma, but it also looks forward, anticipating Pop art’s strategies of ironic appropriation and making Magritte a key reference for the art of the 1960s.