Born in Germany in 1960, Charline von Heyl emerged in the mid-1980s when a tangible sense of optimism and impending change permeated the air. It was a period markedly different in tone from the previous muscular, frequently ironic, increasingly cynical generation. Von Heyl was part of an ever-growing and eclectic social group including Jutta Koether, Cosima von Bonin, Merlin Carpenter, Isabelle Graw, Mayo Thompson, Fareed Armaly, Albert Oehlen and Martin Kippenberger. They blended their interests and involvement in music, art, gender politics, class and culture with a pronounced enthusiasm.

In 1994 von Heyl moved to the United States, where she would set up not one, but three studios. Two of these, in New York and Marfa, Texas, are dedicated to painting. The third, also in New York, is reserved for drawing and printmaking. These separate studios are significant for the artist, allowing her to concentrate on each element of her practice without distraction, and increasingly the processes operative in the prints and drawings – photocopying, collaging, tearing and juxtaposing – are becoming important to the paintings.

The recycling and redeployment of associative images over time is characteristic of von Heyl’s work, where motifs and techniques recur, sometimes after a period of several years. In the early work you can see multiple art historical references, while in her more recent painting the re-used fragments echo aspects of her own practice. Her recycling of material is never simply a form of pastiche or appropriation. Rather than being recognisable, it is mutated and transformed until its source becomes untraceable and irrelevant. It is this feature that makes von Heyl’s paintings so compelling. They are not simply patchworks of quotations from the past, but enmesh these quotations within the fabric of the present.

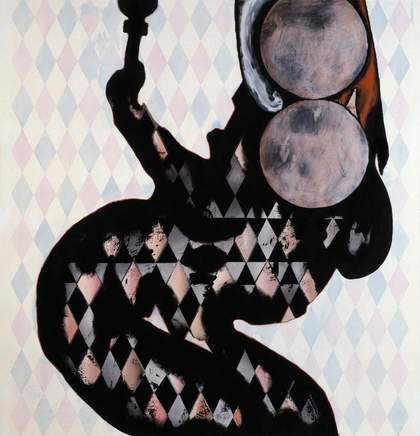

The painterly space she creates is not illusionistic in a perspectival sense. Neither is it the literal material surface of the canvas. Instead, it is a fusing of paint, pattern, colour and imagery that almost hovers in front of the canvas, materialising as if it has been digitally generated, even corrupted like a digital file. Moving away from the manual manipulations of her earlier work, the recent paintings employ processes of masking, layering, distorting, filtering and cloning which have more in common with image manipulation programs.

This relationship to the digital is worth reflecting upon, because von Heyl is very much a studio-based practitioner, who doesn’t use computers in the making of her paintings. None the less, the spatial layering is akin to looking at multiple windows on a computer screen. This new visual field would have been impossible before the age of technological mediation.

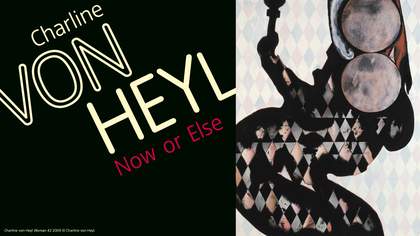

Charline von Heyl

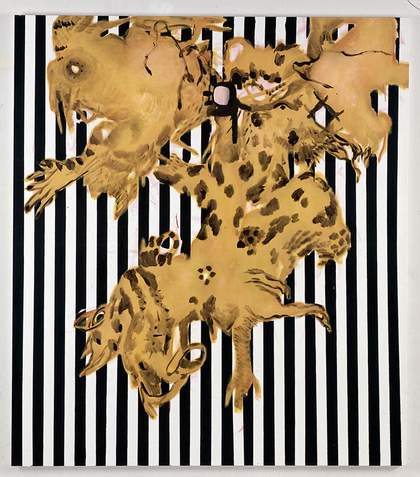

Black Stripe Mojo 2009

Acrylic and oil on linen

208.3 x 182.9 cm

Charline von Heyl's studio

Marfa, Texas, November 2011

I met Charline around 1998 at a party in Chelsea. I remember perfectly the indelible image she made as she walked down the bar towards me, her smile shooting light everywhere. We were instant friends. Not long after that I went to her studio and saw her work for the first time. I had the same experience I always have when I’m in front of it: sheer astonishment, wonder, surprise. The paintings resembled weird aggregates of styles I half recognised – a bit of Wols here, conversing with Pierre Soulages over there – with lots of very unusual colour creating a living sensation of air, earth and respiration. Her paintings have a way of lodging themselves in my mind, where they proceed to behave unlike paintings at all – more like crazy cosmic engines, enacting hilarious tragedy, unflinchingly intense yet detached, churning out this atlas of future shock.

Through the many years of visiting each other’s studios and talking about art and everything else, Charline remains my go-to girl when I’m looking for an honest and forthright appraisal of something I’m doing. I’ve always felt with her a sense of common purpose, ambition and predicament: that painting should engage an urgent sense of responsibility to life in this moment, yet with no roadmap for how to even begin, there is a void which begs the questions: what is real? What can be made vivid? What is the cost of launching oneself into this act against all odds of making it new and vital?

Charline answers this challenge with extreme risk, fresh and unique brilliance, prescient humour. What’s so wonderful about it all is her clarity of purpose, and yet that clarity is mutable, flexible, fleet of foot, responsive to the renewed conditions of every painting. a single work may contain more visual possibility and variety of detail than formerly thought present in the whole enterprise of abstraction; the entirety of her œuvre multiplies that effect exponentially, opening a capacious encyclopedia of stylistic diversity and pictorial imagination. a sophisticated sensibility unites this mass of images, and a consistency of intent makes her paintings recognisable not for what they look like, but for the effect they produce. They flood the mind with interpretations, yet drain them away just as quickly. By upending expectation at every turn, she seems to say: here’s an answer to all the questions, but only for right here, right now. In this way, her paintings resist meaning, and keep me looking and thinking – and rethinking.

To create such resonance with images alone seems impossible, certainly preposterous. But what amazes me about Charline is exactly that: her synthesis of the practical and the preposterous, a dual sensibility born of the extraordinary necessity of our time. I’m speaking of the fierce psychic insight so evident in her art, but also of her stunning ability to execute original work unceasingly and indefatigably.

If encountered with eyes wide open, an extravagant plenitude spills out from Charline’s painting, yet from within her strange and stark demonstration of subjectivity, each work holds its own.

Jacqueline Humphries