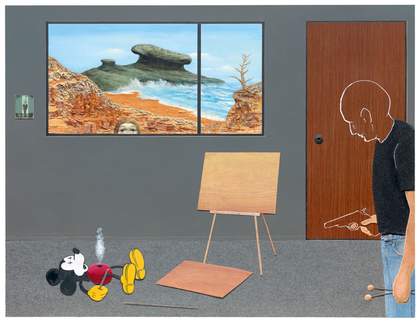

Llyn Foulkes

Deliverance 2007

Oil and mixed media on canvas

Courtesy the artist and Kent Fine Art, New York © Llyn Foulkes

Growing up in Yakima, Washington, I began drawing Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck at the age of five. When I was ten I wanted to be a cartoonist, and at the same time discovered the cartoon music of Spike Jones. That started me collecting horns and bells and playing music. Then I gave it all up when I was seventeen and discovered art through The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, a book I borrowed from the library.

When I arrived in Los Angeles in 1957, the art scene was extremely small – until the magazine Artforum moved from San Francisco down to L.A., right above the Ferus Gallery, and things really picked up. A major early influence was de Kooning and a particular painting called Merritt Parkway 1959, which had a big slash of white coming down that looked like a cross, and I realised: ‘Oh my God, that’s like a religious painting.’ Anthropomorphic images became influential to my own work.

I had a lot of critical success with my 1960s burned blackboards and chairs, assemblages and combines, and early shows at the Ferus Gallery (nine months before Warhol’s first show there) and at the Pasadena Museum in 1962. I was incorporating everything from collage to dead animals and textures to improve the photographic effect, and the works had a whole dark edge to them, using tar as paint. Just like I had an edge: wearing all black, owning a raven and collecting taxidermy animals.

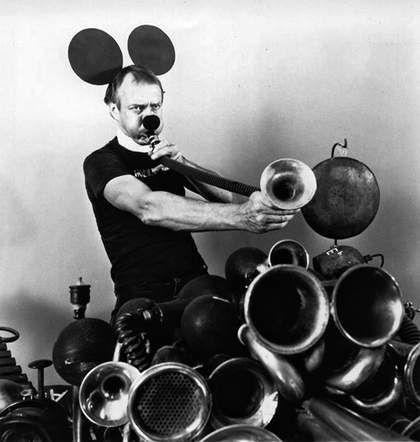

Llyn Foulkes playing his 'machine'

Courtesy the artist

Then in 1963 came the Rolf Nelson Gallery exhibition with cows and serial imagery of surrounding landscapes. Irving Blum brought Warhol to see it twice, which I am sure influenced his cow wallpaper that he showed three years later at the Ferus. There were additional early painting successes with awards and attention at the Paris Biennale (1967) and as the representative of the United States at the Saõ Paulo Biennial curated by Jim Demetrion. This culminated in a sell-out show of large rock landscape paintings in Paris at the Darthea Speyer Gallery in 1970.

My first wife happened to be the daughter of Ward Kimball, Disney’s head animator. Ward gave me a copy of the first page from the 1934 Mickey Mouse Club handbook with its blatant mission to ‘implant beneficial principles’ into the minds of children, which would become a permanent subtext to my paintings. With the beginnings of success as a painter, I was invited to be a teacher at UCLA, and started playing the drums in a rock band from time to time.

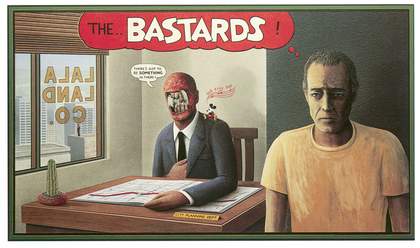

Llyn Foulkes

Rape of the Angels 1991

Mixed media on canvas

Courtesy the artist and Kent Fine Art, New York © Llyn Foulkes

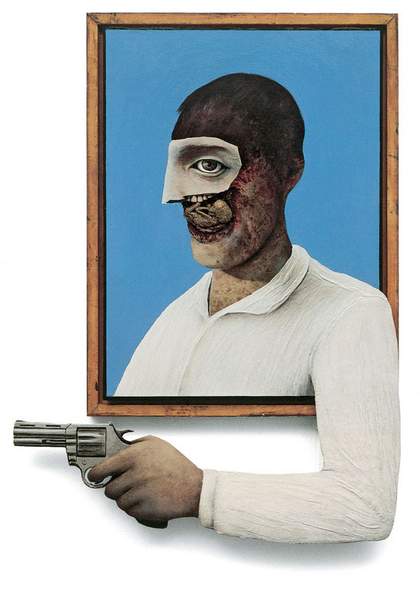

Llyn Foulkes

Double Trouble 1991

Mixed media

Courtesy the artist and Kent Fine Art, New York © Llyn Foulkes

As the rock paintings became more and more popular, I started having real doubts about what I was becoming as a painter. Things were falling apart, and as a direct result of therapy sessions in 1971, I began my ‘bloody head paintings’. These new works and ideas were so intense, I went into my studio and destroyed a 10 × 12 ft rock painting. I began to get into more political subjects, making a bloody head of Richard Nixon and one about the Battle at Wounded Knee. The heads have held my interest in terms of their enduring intensity and honesty. Right now, I am re-exploring the painterly possibilities of working with the human face.

Beginning in the early 1970s, music came back in full force with my band The Rubber Band, with all original music and lyrics written by me. We broke up after a performance on the Johnny Carson Show, and from that point forward, I became a one-man band, with the creation of an elaborate percussion, bass, horns and flexi-phone construction of my own design, which I refer to as ‘The Machine’.

As the ideas in my lyrics began to merge with the concepts behind my paintings, I made another shift in my work.

Beginning in 1983 with The Last Outpost and O’Pablo, I began to experiment with three-dimensional space in painting. I dedicated five years to one painting entitled POP 1985–90, which was installed in a darkened room in the Museum of Contemporary Art’s seminal show Helter Skelter. It created quite a sensation. These new works have taxed my abilities to the limit, always taking years to complete, and never actually seeming to be done.