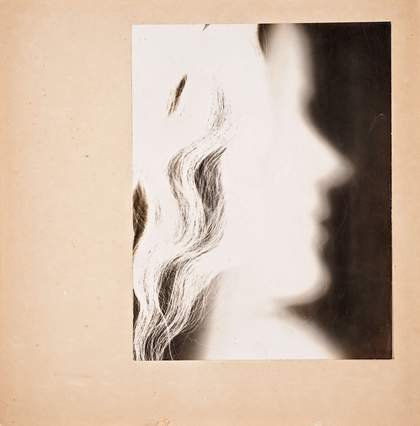

‘I am doing Photograms! I am having such fun,’ Barbara Hepworth wrote to Ben Nicholson (then in Paris) at the end of 1933: they ‘reveal the most beautiful new world of light & form’.

Hepworth’s pair of self-photograms are the only surviving examples from this moment of excited experimentation, inspired by contact with László Moholy-Nagy, who was making his first visit to London. One of the pioneers of the photogram, and the inventor of the self-portrait photogram, Moholy-Nagy had just published his major article in The Listener, ‘How Photography Revolutionises Vision’, arguing for the revolutionary potential of this completely dematerialised, camera-less medium. The friendship deepened after he settled in London between May 1935 and July 1937, a refugee from Nazism. He was invited to contribute to ‘Circle: International Survey of Constructive Art’ 1937, and he and Hepworth appear to have swapped works.

Although the photograms are unique in Hepworth’s work, they can be seen as an aspect of her interest in photography, shown for example in the photographs she and Nicholson took in the Mall Studio they shared, featuring each other’s profiles. They relate especially closely to Nicholson’s painted, drawn and incised profiles of Hepworth in his work of this period, such as the linocut Profile 1933, as well as referring to her own sculptures with incised profiles. They owe a clear debt to Moholy-Nagy’s self-photograms of the mid-1920s, in which he had laid his head of a sheet of light-sensitive paper. Hepworth painted only one self-portrait, in 1950 (National Portrait Gallery), heightening the preciousness of this early pair.