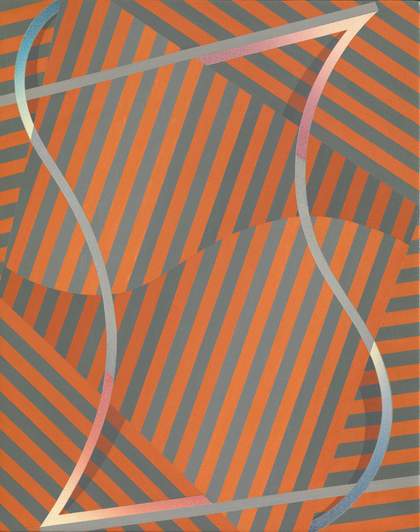

Tomma Abts

Zebe 2010

Tate © Tomma Abts

The history of art of the past century is as much a history of painting as it is a history of its demise. Painting has continued to occupy a privileged position, and yet it is a position that has been continually under threat. Now, at a time when the realities of daily life and material culture increasingly form the subject of art, painting might seem redundant as a medium at one remove from such subjects, defined by an activity and process that from such a perspective perhaps appears anachronistic. Yet within the past five or more years, following a period in which medium specificity and the boundaries between media and practice have largely been eroded, painting once again, seemingly against the odds, holds attention and is in a period of renewal.

Painting Now: Five Contemporary Artists is an exhibition that emphasises new possibilities for painting. Each artist in the show, albeit in different ways and degrees, ascribes a significant place to painting as a critical way of looking and making – both thinking about what painting might be and looking out for new positions for painting.

The paintings of Tomma Abts (born 1967), for example, explore a concentrated language of form, space and volume. And yet they are not ‘abstract’ in that they oscillate between an attention to how they are made and the work that results, which is often a pictorially constructed illusion. Each painting is achieved through a cumulative sequence of intuitive yet complex decisions initiated from the first mark. The finished picture doesn’t necessarily display the layers of mark-making, but the sense of the painting as wrought object is clear to see. This particular sense of material then exists in contrast to the image which offers a depicted illusion of space.

Such a play of illusion is not a result of moves that are about abstraction or figuration, but instead describes a push and pull between the painterly (to do with material and process) and the pictorial as a deliberate construction of image. It is this tension between the painterly and pictorial that provides one location for the subtle affinities that may be discerned between the five very different artistic positions in the exhibition.

Simon Ling

Untitled 2012

© Simon Ling Photo: Marcus Leith. Courtesy of greengrassi, London

For Simon Ling (born 1968) this position is played out in terms of observation. Broadly speaking, he makes landscape paintings in the open air, directly in front of his motif, or he puts together a tableau in his studio, which he then paints as a form of still life composition. While these studio constructions are wholly artificial, his landscape paintings depict places that might seem mundane or banal, where categories of artifice and nature shift – London Zoo, scrubland, or the buildings around Old Street in London. Although the paintings are constructed out of a studied sense of observation, Ling is driven to capture not what the motif may look like, but the experience it engenders, in such a way as to create a degree of emotional equivalence that exists between looking and matter, resolved through an attention to particular compositional structure.

Gillian Carnegie

Prince 2011–12

Margot and George Greig © Gillian Carnegie Photo: Lothar Schnepf, courtesy Galerie Giesla Capitain, Cologne

Gillian Carnegie (born 1971) similarly follows a path that is seemingly determined by a traditional approach to a restricted range of subject (still life, landscape, the figure and the interior). And yet her apparent concern with pictorial realism is not clear-cut. She seeks to close down narrative content, and her repetition of a stock of motifs effectively acts as a barrier to meaning. The making of a painted representation is furthermore emphasised to be a thing in itself, rather than just a depiction. As she has said: ‘I prefer to consider the painting as a thing in the world rather than the painting as a picture of things in the world.’

Catherine Story

Lovelock (I) 2010

Private collection, London © Catherine Story

Photo: Andy Keate. Courtesy Carl Freedman Gallery, London

This tension between the subject of a painting and its material state also illuminates the strangeness of the paintings of Catherine Story (born 1968). Her work shifts register between material and dimensions – for instance, sculpture and painting often exist alongside each other with no stated hierarchy of process. Questions of materiality and dimensionality also ground her long-held interest in cinema and film as a subject. Film conjures up illusory worlds in which dancing patterns of light are made actual and real on the screen. For example, painting a vintage movie camera as if it is both Cubist still life and personage animates complex histories of looking and feeling that transform how the work is understood, whereas picturing the lattice structure of a pylon as a solid form and making the painting on baking paper projects an image that is familiar and solid, yet difficult to place and ultimately fragile. To a degree, Story’s paintings are re-formed images that capture the wonderment – the reality and evanescence – of the dancing dust motes caught in a cinema projector’s beam.

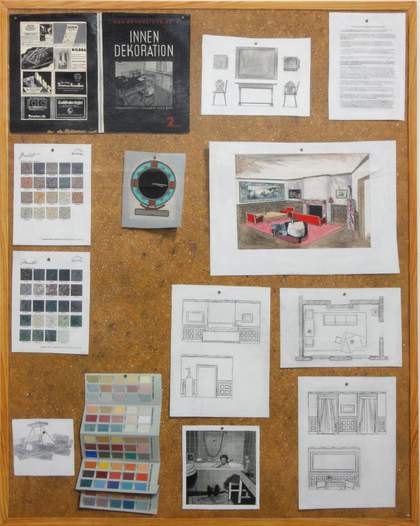

Lucy McKenzie

Quodlibet XXII (Nazism) 2012

Private Collection, Belgium © Lucy McKenzie Photo: courtesy Galerie Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp

For each of these artists in very different ways, the activity of painting can be understood as a process of resistance as much as it is affirmative. For Lucy McKenzie (born 1977), painting is also a tool. She deploys craft skills – marbling, engineering drawing, or trompe l’œil, for instance – not for simply decorative reasons, but to communicate particular meaning and imbue it with critical purpose. Craft is just the medium for her ideas. In this respect, craft techniques and interior design succeed on the one hand as mute decoration, but are at base socially and politically directed in terms of the degree to which they exemplify ideals about designs for living. It is not surprising that for McKenzie, painting sits alongside fashion design, performance and curating; she is exemplary in finding a way to re-purpose the critical weight painting can bear through her engagement with each collaborative activity. Here, painting’s crisis of identity – craft or art, stated baldly – is not carried through in terms of a rootless postmodernist hybridity, but as a means of drawing the viewer into a social compact with the work, so that it may even be ‘inhabited’ by the viewer.