Almost as soon as there was photography, there were photographs of ruins. It makes sense of course: the invention of the daguerreotype and its competitors comes only 50 years after the height of the enthusiasm for ruins that had seized European art and literature in the eighteenth century and found its most pervasive and popular expression in the craze for the picturesque. Classical and medieval ruins remained natural subjects for artists in the early decades of the new century, and an aesthetic of pleasing decay can still be divined in the early experiments of photographers such as William Henry Fox Talbot. But photography swiftly adds another layer to the taste for ruins, or perhaps strips one away: the nascent technology is as likely to be turned without nostalgia (but perhaps with regret) on new destruction, or on recent collapse, as on ancient relics and fragments. To photograph ruins also means turning one’s gaze on the present, and towards the future.

For sure, there were conscious efforts in the early decades of the medium to capture precisely (and even bureaucratically) crumbling relics of the past that traditional art forms had addressed but not exhausted. In France, representatives of the state-sponsored mission héliographique were dispatched to record the country’s extant Roman ruins: the likes of Édouard-Denis Baldus framed structures such as the Roman theatre at Arles in ways that recalled the paintings of Hubert Robert (known as ‘Robert des Ruines’) just a few decades earlier. In a similar mode, Maxime du Camp photographed the antiquities of Egypt, complete with just the kind of tiny scale-hinting human figures who populated the engraved visions of eighteenth-century ruin-mongers.

Among the modern travellers was Charles Marville, who photographed the ruined medieval churches of France before concentrating on present ruination, becoming point-man for Baron Haussmann and surveying districts of old Paris, then in the process of being pulled down and replaced with wide, clean (and in Marville’s pictures, quite empty) boulevards. By the 1860s ‘ruins’ were as likely to be seen and photographed in the next street as the Holy Land or the touristic vistas of Rome.

Jane and Louise Wilson

Azeville 2006

Tate © Jane and Louise Wilson, courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

In the nineteenth century the British case is just as conflicted regarding the timescale of photographed ruination, and the confusion sets the terms of ruin aesthetics for many artists and photographers to come. The photographic scrutiny of national ruins and relics tended, though, to be underwritten by moneyed amateurs or bands of enthusiasts that only slowly coalesced into pressure groups and semi-state bodies.

In the 1870s one such organisation turned its attention to certain unlikely fragments of the relatively recent past. The Society for Photographing Relics of Old London originated in 1873 in a campaign to save an ancient inn, the Oxford Arms, situated in Warwick Lane. It was eventually pulled down in 1877, but in the meantime six prints had been made showing the quaint, tumbledown establishment with its creaky- looking wooden balconies. (In print number six, the dome of St Paul’s cathedral rises above the chimney pots: a familiar sight in visions of London in ruins, such as Gustave Doré’s engraving The New Zealander, 1872.) The society carried on for twelve years, saving many buildings in the city, and publishing 120 photographs of the relics in question.

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Tintern Abbey: The Crossing and Chancel, Looking towards the East Window (1794)

Tate

These images are modest counterparts to those Marville was still making in Paris, or the views of doomed squares and streets which Eugène Atget would produce around the end of the century. The Society for Photographing Relics of Old London points the way towards a dominant trend in British photography of urban and rural ruins alike: it comes out of an interest precisely in the remains of the recent past, and from a willingness to rethink comprehensively definitions of ‘ruin’, ‘relic’, ‘monument’ or (to use a much later term) ‘heritage’ when catastrophe or decay make it essential or interesting to do so. Consider Paul Nash’s pre-war images - taken, like all his photographs, with a simple Kodak pocket camera - of fragments of ‘Seaside Surrealism’ (as he put it in an essay for Architectural Review in 1936) and rural or semi-rural collapse: the rampant tree trunk of his Monster Field 1938, or a set of concrete steps stranded in a field near Swanage in Dorset.

Nash’s most self-conscious and radical evocation of traditional ruin lust comes, however, in the photographic studies he made for his painting Totes Meer 1940-1, at a dump filled with wrecked aircraft in Cowley, Oxfordshire. Here, the tortured forms of dead machines resemble very explicitly the sheets of ice that encase a crippled ship in Caspar David Friedrich’s The Sea of Ice (1824). Nash wrote of the scene: ‘A pervasive force baffled yet malign hung in the heavy air’ - malign because truly deathly, baffled perhaps because the technological products of total war had come to resemble the forms of a century-old Romanticism. (In the history of photographic responses to the Second World War, one could jump-cut forward here to Jane and Louise Wilson’s photographs of the Nazis’ fortified Atlantic Wall. Such is the nature of modern ruin aesthetics: the timescales tend to get confused.)

Some of Nash’s snapshots of anonymous residua now resemble, rather oddly, the photographs produced by a later generation of artists as they strove to reckon with and in part demolish the tradition of British landscape art. Land Art and Conceptualism relied heavily on photographic documentation, and there are works by Richard Long, for example, that can be read as species of very minimal ruin: fleeting interventions in the landscape that are about to fade away. In a seemingly more documentary vein, for his early 1980s series A.O.N.B.(Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty), Keith Arnatt revisited sites celebrated by the pioneer of the British picturesque, William Gilpin, in the pages of his Observations on the River Wye 1782. In Arnatt’s hilarious and conceptually devious photographs, the ruins Gilpin hymned are still intact, though absurdly overwritten by the trashy infrastructure of modern tourism. (Not that there was not vulgar sightseeing in Gilpin’s day, very largely because of his books.) A pitch-roofed sign for the Anchor Hotel dwarfs the crumbling wall and vacant arches of a ruined church or abbey; the towers and ramparts of a castle are seen through a children’s climbing frame in the shape of a space capsule; the tarmac and markings of a car park abut absurdly a fragment of ivy-hung stone wall.

Keith Arnatt

A.O.N.B. (Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty) (1982–4)

Tate

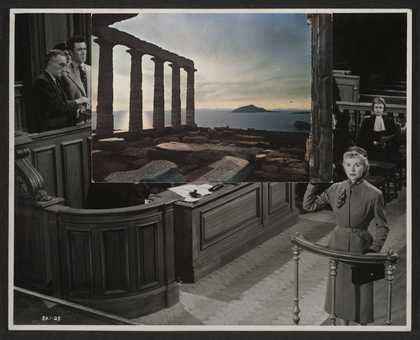

John Stezaker

The Oath (1978)

Tate

For the Victorians, the ruin lust of the previous century could be repurposed to describe an altogether more pressing anxiety, and as in Doré’s engraving, or Richard Jefferies’s 1885 novel After London, the subject was frequently the ruin of the capital. That fantasy has not ceased to inspire and haunt certain artists, and not only in the wake of the destruction of the Blitz. In 1953, in her classic study Pleasure of Ruins, Rose Macaulay reflected on these ‘new ruins’, and concluded that they would in time attain the picturesque vagueness of their traditional counterparts - for the moment, they were still too vivid and raw.

In the last decades of the twentieth century, it seems to have been the very idea of the new itself that was subject to ruin. The present enthusiasm for modern ruins has precursors who would likely not have used the aesthetically loaded term at the time. Jon Savage’s photographs of a bleak and seemingly vacant London, made in the late 1970s, depict one grey terminus for the dream of post-war reconstruction. Another is the decline of modernist architecture itself, as in Rachel Whiteread’s Demolished series of 1996, which shows the erasure of tower blocks on three estates in Hackney.

If the idea of ruin has lately returned, it is with a sense that the word and the sensibility it names might as easily be discovered in the present, or projected into the future, as divined in the detritus of the past. So that when we speak of ruins in contemporary art we might be talking of relatively ‘straight’ photography such as that of John Riddy, whose images of contemporary London are inflected by a deep knowledge of the ruinous art of the past. We might point to the ruin as recurrent motif - and perhaps analogue for the artist’s own methods - in the photomontages of John Stezaker. Or to works that only fleetingly or obliquely feature actual physical ruins, and engage rather the wreckage of an idea or desire directed at the future: Gerard Byrne’s video installation 1984 and Beyond 2005-7 restates a conversation, originally convened in 1963, among sci-fi writers who were asked to imagine life in 1984. In the accompanying black-and-white photographs, we might be in mid-twentieth-century America, in the era of world’s fairs and gleaming modernist precincts - but it is the present, our present, looking still like the future and slipping into the past.