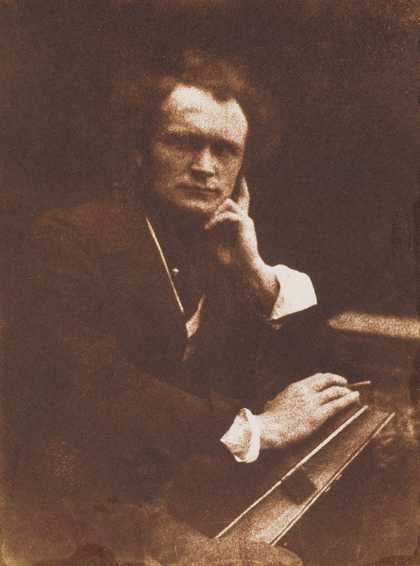

DO Hill and Robert Adamson

Thomas Duncan 1843–4

Salted paper print from paper negative, 148 x 111mm

Courtesy Wilson Center for Photography

Early photographs absorb us in many ways. Their imagery has the directness and freshness of something made for the first time, made new. They also link us to the past and its protagonists: photographers, sitters and viewers. The pictures in Salt and Silver: Early Photography 1840–1860 – simple prints of silver and salt fixed on plain paper – were created at the beginning of photography’s evolution using William Henry Fox Talbot’s processes.

His methods and materials were efficient, portable and versatile, but commercial portrait studios first favoured the daguerreotype process and paper photography was largely the domain of amateurs. They were a diverse contingent; some, like Talbot, were scientists. Robert Adamson studied mathematics and trained to be an engineer, while his collaborator David Octavius Hill was a lithographer and painter. Their partnership began in 1843, just four years after photography’s public announcement, and yet within another four years they produced almost 1,500 remarkable photographs. They were, as the German writer and philosopher Walter Benjamin declared in 1931, key to ‘the flowering of photography’ which ‘came in its first decade’.

The appeal of their work includes the compelling materiality of their salted paper prints. This is Talbot’s process, where the light-sensitive salt and silver are applied in solution, soaking into the upper layers of the paper. The image is thus integrated into the paper, creating a sense that the photograph is itself an object rather than an image sitting on top of a coating as in the mid- 19th-century albumen print or the later gelatin silver print. The plain matt surface has a velvety richness, especially in the deeper tones, while the paper fibres subtly break up the outlines of the image, giving a rough softness to the picture.

This pictorial breadth is very different from the fine detail of daguerreotype images. By comparison with the precision achieved on those polished silvered plates, paper prints could look sketchy and provisional. Yet they were appreciated for just those qualities. In 1843 the Edinburgh journalist Hugh Miller described Hill and Adamson’s photographs in the terms of a painted portrait: ‘There is the same broad freedom of touch… all is solid, massy, broad; more distinct at a distance than when viewed near at hand.’

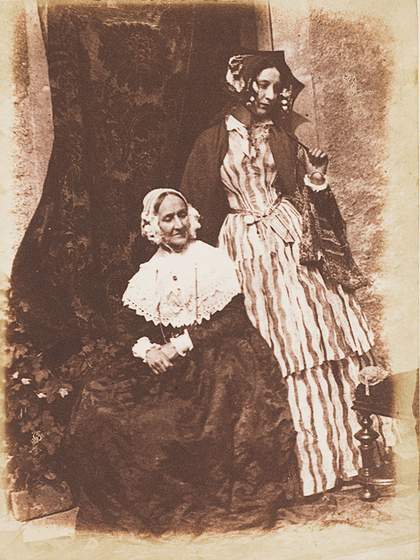

DO Hill and Robert Adamson

Mrs Anne Rigby and Miss Elizabeth Rigby (later Elizabeth, Lady Eastlake) 1844–6

Salted paper print from paper negative, 210 x 160mm

Courtesy Wilson Centre for Photography

Over the next decade, photographic materials became more sophisticated; glass plates replaced paper negatives and smoothly coated albumen supplanted salted paper. But Hill’s friend and sitter Elizabeth Eastlake was not won over by the new technologies. Writing in 1857, she praised the ‘broad light and shade’ of older photographs as a perfect match of aesthetic and materials, giving ‘artistic pleasure of a very high kind’. As an art historian and the wife of the director of London’s National Gallery, she was well placed to make aesthetic judgments. Improved image resolution was all very well, but art had been sacrificed: ‘Far greater detail and precision accordingly appear… what was at first only suggestion is now all careful making out – but the likeness to Rembrandt and Reynolds is gone!’

While other printing papers superseded salted paper prints, the process did not disappear; it remained a practical resource for colonial outposts and a medium for hand-tinted portraits. And salt prints persisted out of aesthetic preference. In the 1890s a dedication to craft and authorial control led photographers to make the prints by hand as an alternative to commercially manufactured printing papers.

Hill and Adamson’s photographs also endured. They were reprinted throughout the 19th century by the Glasgow firm T and R Annan, and between 1905 and 1912 published by Alfred Stieglitz in four issues of his journal Camera Work. Stieglitz exhibited their work in New York in 1914, as did the art historian Heinrich Schwarz in Vienna in 1929. Schwarz’s 1931 book on Hill inspired Benjamin, who famously wrote of ‘the first photographs’ reaching across the years to ‘emerge, beautiful and unapproachable, from the darkness of our grandfathers’ day’.

We are now nearly as far from Benjamin’s time as was he, in 1931, from Hill and Adamson’s, but at Tate Britain the first photographs emerge again to connect us with a rich history of photographic invention.