Trevor Paglen

Untitled (Predators; Indian Springs, NV) 2010

C-print, 1524 x 1219mm

© Trevor Paglen, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander

In the months after the attacks on the World Trade Centre on 11 September 2001 a significant number of artists and cultural practitioners compared the events, in all their visual impact and operatic pitching of good against evil, with a work of art. These comments were dismissed at the time as reactionary and in bad taste, but they did reveal an imminent desire to develop a degree of distance – be it aesthetic or otherwise – from the emotive, ‘spectacular’ and brutal realities that unfolded on that fateful day. In the months and years that followed, under the political logic of a so-called war on terror, we saw yet another unprecedented attack, this time on the legal systems protecting basic civil rights. The war on terror segued, in short order, into an assault on human rights. For some, terrorism has become the single biggest challenge facing democratically elected governments worldwide. For others, it is the political reaction to it that has done more to weaken democracy than any act of terror.

Executed as it was in the name of justice, the war on terror has resulted in a nominal state of emergency being declared across North America and Europe. Since 2001 we have witnessed the repeated suspension of due legal process, the revocation of constitutional law, the institutionalisation of torture, the withdrawal of civil rights, the deployment of mass surveillance, the routine collection of information on innocent citizens and arbitrary detention without trial for countless people worldwide.

Contemporary artists, in examining the ambiguity of this state of affairs, often create narratives and forms of speculative visual rhetoric that expose the anxieties surrounding these acts. It is increasingly notable, for example, that they have turned their attention away from the original attacks on the World Trade Centre and now focus more readily on the intransigent and highly politicised discussion about terror, terrorism and human rights that ensued.

The suspension of due legal process in the aftermath of 11 September is explored throughout Trevor Paglen’s Seventeen Letters from the Deep State, a work from 2011 that consists of photocopies of a series of letters from the US State Department. Each document is signed by someone called Terry A Hogan, who is seemingly authorising acts of ‘extraordinary rendition’ and the subsequent apprehension and transfer from one country to another of anyone deemed an ‘enemy combatant’ or a danger to national security. Seen together, the signatures are notably different from one another, and evidence subsequently unearthed by both journalists and lawyers indicates that Hogan never existed.

Seventeen Letters from the Deep State stems from an earlier project, 2006’s CIA Rendition Flights 2001– 2006, a collaboration between Paglen and the activist and graphic designer John Emerson. Together, the two men documented the movements of aircraft that were either operated or owned by companies contracted by the CIA to transport suspected terrorists to countries where torture is condoned.

Here, a sense of clandestine deviation, in terms of suspended due legal process and lawful representation (under the guidelines proposed by habeas corpus), would again appear to be the rule rather than the exception in relation to the politics of modern-day terrorism.

For many, the spectre and reality of the detention camp, in all its manifestations, has become the exemplification of this suspension of due process. Often extra-juridical by nature, it is in these spaces that government representatives have apparently performed a gradual, sometimes fatal, recalibration of what we consider to be humane treatment, alongside what we understand as the very notion of what it is to be human.

Cristoph Büchel and Gianni Motti’s Guantánamo Initiative 2004–ongoing at the 51st Venice Biennale, 2005

© Christoph Büchel and Gianni Motti, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

The continued existence of the US military prison at Guantánamo Bay, with its questionable status and the unresolved fates of its inmates (known as ‘unlawful enemy combatants’), further confirms that legal process is relative and, in times of apparent, self-proclaimed emergency, its systems of checks and balances can be overridden to suit political ends. At the 51st Venice Biennale in 2005 Christoph Büchel and Gianni Motti staged their Guantánamo Initiative (2004–ongoing) to draw attention to the interstitial location and legal status of this so-called detention centre. Requesting a new lease from the Cuban government for Guantánamo, so as to transform it from a military to a cultural base, the artists displayed treaties and documents to expose what they viewed to be the illegitimacy of the US lease contract imposed on Cuba in 1903. They also displayed 47 annual rent cheques – all of which the Republic of Cuba has refused to cash – that have been issued by the United States since 1959.

The camp remains a central component of Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri’s Camp Campaign, ongoing since 2006, and the basis of a simple question: what are the conditions of the camp’s continued existence? Setting off from New York City on a road trip across the United States, the duo continued to ask this question, transforming it into an investigation. They encouraged their audiences to explore the many associations of the word camp, including detention, internment, refugee, relief and even holiday. I n their approach to terror and the politics that surround it, a number of artists have chosen to investigate its physical and psychological aspects, including torture and the experience of terror. Consisting of a series of corridors with cells attached to them, Gregor Schneider’s White Torture of 2007 is concerned with sensory deprivation and isolation. The installation was inspired in part by images downloaded from the internet of Camp 5 at Guantánamo Bay. One door leads into a cell with a green steel cage in it, another into a pitch-black corridor, and yet another into a white corridor; all the while, a soundtrack of cell doors being opened and closed plays in the background. The overall effect is extremely disorientating, as might be expected from a work designed to explore torture techniques used to confuse individuals and render them more susceptible to interrogation.

Image for promotional poster for Wafaa Bilal’s performance Dog or Iraqi 2008

© Wafaa Bilal, photograph © Kari Laydersen

In Wafaa Bilal’s Dog or Iraqi, from 2008, visitors to a website were invited to vote on whether the artist or a dog named Buddy should be subjected to waterboarding, a form of torture in which water is poured over a cloth covering the face of the restrained prisoner, causing them to experience the sensation of drowning. Apart from death, brain damage, lung failure, extreme pain, oxygen deprivation and other physical side-effects, this can inflict long-term psychological damage. In accordance with the result of the vote, it was Bilal who was waterboarded at an undisclosed location in upstate New York. In the short clip that documents the event, the artist is shown panicking and retching after only a few moments, leaving us to imagine what repeated and lengthy subjection to such torture could do to a person.

Utilising research and theatrical forms of reenactment, in 2006 Coco Fusco re-staged the trauma associated with interrogation in detention camps such as Guantánamo Bay but without directly representing that trauma. For Fusco, the camp comes with its own internal and highly schematised systems of abuse. In Operation Atropos, a 59-minute film, she was joined by six women – all dressed in orange jumpsuits referencing the ubiquitous clothing worn by inmates of Guantánamo – who enrolled in a training workshop run by Team Delta, a cohort of retired US military interrogators. We watch as the volunteers are ambushed, bound, have their heads covered, and are thereafter subjected to ex-military personnel performing, with brutal verisimilitude, the role of guards and interrogators.

Terror and the apparent threat of terror has and continues to legitimise the use of torture and socalled ‘black ops’, which often involve the forceful rendition of terror suspects. To these already grave concerns, we have seen a lexicon emerge that includes terms such as bioterrorism, racial profiling, biopolitical surveillance and, increasingly, the criminalisation of organised protest and artistic practices that engage with these issues.

Video still from Coco Fusco’s Operation Atropos 2006

Courtesy the artist

Video still from Coco Fusco’s Operation Atropos 2006

Courtesy the artist

Video still from Coco Fusco’s Operation Atropos 2006

Courtesy the artist

On the morning of 11 May 2004 Steve Kurtz, one of the members of Critical Art Ensemble (CAE ), a group of five artists who produce film/video, photography, text art, book art, computer designs and performance, woke to discover that his wife Hope had died in her sleep. Following a call to the police, he was subjected to questioning by the FBI about a biology lab in his house. Detained for 24 hours and then freed, he and CAE ’s other members were none the less ordered to appear before a grand jury to answer bioterrorism charges. Despite being cleared in July 2004, the FBI continued to press charges against Kurtz until 2008. The politics of art, in this context, can sometimes come into vertiginous proximity with anti-terrorism legislation and illconceived forms of political fatalism.

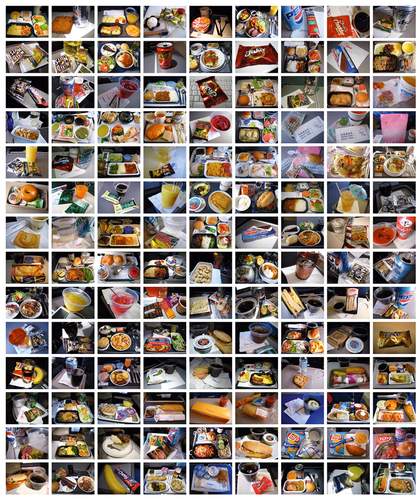

The personalisation of information for political purposes and surveillance today is taken to its extreme in a work by Hasan Elahi. Having been detained and questioned at Detroit Airport in June 2002 for supposed terrorist activities, Elahi was subjected to a further six months of questioning before being cleared of all suspicion. Concerned that he would run into similar problems the next time he tried to re-enter the United States, he began voluntarily to inform the FBI of his whereabouts. What began with a few phone calls and emails eventually developed into Tracking Transience 2002– ongoing, a comprehensive account of his daily activities, including photographs of his meals and a website (www.trackingtransience.net) that records his location several times a day. In this radical form of self-surveillance, Elahi raises questions about the politics of terror legislation and the technologies being deployed on whole populations in its name.

Photographs from Hasan Elahi’s series Tracking Transience 2002–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

On the morning of 11 September 2001 Gerhard Richter and his wife were travelling to New York when, at 8.45, their flight was diverted by the Federal Aviation Authority. A hijacked aeroplane had just crashed into the World Trade Centre. Richter later painted September 2005, but refused to exhibit the work for some time, even considering at one point destroying it. For an artist who had confronted some of the most traumatic events in German history, including the Second World War and – in his seminal cycle of paintings from 1988, 18 Oktober, 1977 – the arrests and deaths of the Baader-Meinhof gang, 11 September, as both an event and a painting, perhaps represented an all-too-personal reminder of the iconic status that certain images can assume over time. It was also perhaps a reminder of how the then German government politicised the lives and deaths of the Baader-Meinhof members and subsequently criminalised protests across Germany in the wake of anti-terror legislation.

Gerhard Richter

September 2005

Museum of Modern Art, New York © Gerhard Richter

Again, the political reaction to terrorism would appear to do more to undermine democracy than terrorism itself, producing the very effect that terrorists attempt to achieve. In our time, even more so than in Richter’s, we have seen a radically new world order emerge, one in which arbitrary incarceration, torture, unwarranted surveillance and outright murder are deemed appropriate if not necessary for the functioning of democracy. And it is within this grave context that visual culture, which has been and continues to be the target of terrorist legislation, seeks to produce works that question the moral ambiguity and culpability of governments and citizens alike in this process.