Alexander Calder installing Le Guichet 1963 with grandson Alexander S. C. Rower, Lincoln Center, New York, photographed by Bob Serating, 1965

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York/DACS, London, courtesy Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource, NY

Simon Grant You knew your grandfather Alexander Calder when you were a child. In the photograph of you and him from 1965 where he is installing his sculpture Le Guichet at the Lincoln Center, New York, you are a very small boy. What are your memories of him?

Alexander S. C. Rower He was supremely generous and a very social person, who was devoted to his family and loved dinners, parties and especially dancing. Having said that, he was almost always working. From an early breakfast of a soft-boiled egg until lunchtime, he would be in his studio. Then back to work after a quick nap.

SG You were among the select few youngsters to be allowed into his studio. Can you describe that experience?

AR When he was at work, he was in deep concentration – seemingly channelling from another dimension. He was very quiet and serious and did not want to be interrupted. I was welcome in the studio so long as I kept quiet, didn’t break his routine and stayed focused on my own project. He also taught me about his work, his tools, his methods, etc.

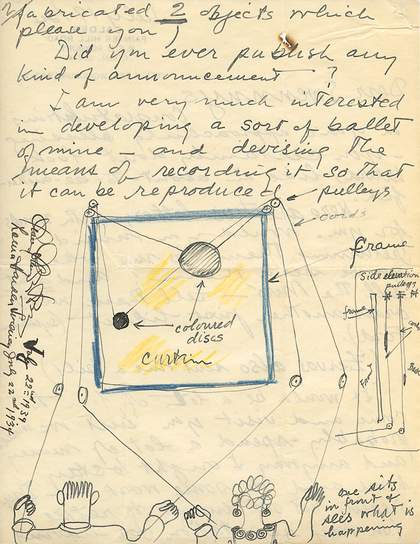

Letter from Alexander Calder to James Johnson Sweeney illustrating A Merry Can Ballet 1933, 19 July 1934

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York/DACS, London, courtesy Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource, NY

SG He came from a line of artists. His father, Alexander Stirling Calder, was a sculptor, as was his Scottish-born grandfather, Alexander Milne Calder (himself the son of a tombstone carver). Was he encouraged to follow in their footsteps?

AR His parents didn’t want him to have the uncertainties of an artist’s life. They knew all too well the difficulties of sustaining a livelihood. And yet after he tried a career as an engineer and finally dedicated himself to art, his family was supportive, even when his abstractions seemed incomprehensible.

SG For many, Alexander Calder is best known for his mobiles and large outdoor sculptures. However, his work was much more complex, radical and experimental than that. In his early pieces (such as A Universe 1934 and Two Spheres 1931) he explored important themes that appeared to echo an age of scientific wonder in the 1920s and 1930s. Was this a coincidence?

AR Certainly he was aware of the extraordinary scientific advancements taking place then. He spoke powerfully in his autobiography of gaining a ‘lasting sensation of the solar system’ while working on a ship in 1922 off the coast of Guatemala, after seeing the sun rising over one side of the horizon as the full moon waned on the other. However, his earliest works were not intended to be specific models of stars, planets, or the universe – a common misconception. Rather, they were a definition of the universal – an exploration of the unifying force postulated by physicists today as string theory.

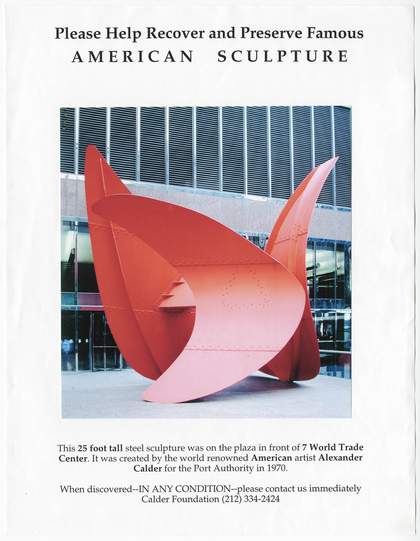

Alexander Calder

Snake and the Cross 1936

Sheet metal, wood, rod, wire, string and paint, 2057 x 1295 x 1118mm

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York/DACS, London, courtesy Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource, NY

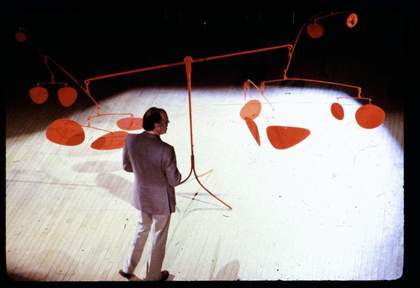

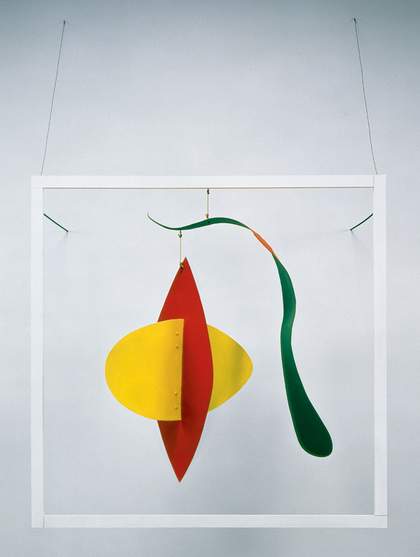

Alexander Calder with Black Frame 1934 at the exhibition Mobiles by Alexander Calder, The Renaissance Society of The University of Chicago, 1935

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York/DACS, London, courtesy Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource, NY

SG The words ‘play’ and ‘playful’ have often been associated with Calder’s work, and, in particular, the mobile has become a fixture in the life of many children’s early years. Some critics thought this idea of play suggested a lightness to his art, but that’s not how he understood these words, is it?

AR Others assigned them to him later in his life and after his death, unnecessarily trivialising his work. As I mentioned, when he was in his studio he was deadly serious, though ‘play’ as a term that refers to a working process of intuitive experimentation certainly applies to his practice. When play equals innovation, then that is Calder’s equation.

Alexander Calder with Snow Flurry I 1948, photographed by Gordon Parks, 1952

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York/DACS, London, image © The Gordon Parks Foundation

SG The idea of performance is often one linked to dance, or performance art, but your grandfather saw it differently. Movement, both in the work and the spectator, seems central to his practice…

AR It was intrinsic to his work. One of his great innovations – that of the mobile, an entirely new art form – was based on his desire to see sculpture move. But he always had an interest in movement, which can be seen even in his Cirque Calder 1926–31 and the early, wire sculptures. I think that’s why he had such fruitful collaborations with dancers and choreographers, such as Martha Graham, Joseph Lazzini and others.

SG How did music shape his work – I’m thinking of his collaborations with both Erik Satie and Earle Brown?

AR Throughout his career, he made sound-related objects. In fact, the earliest mobile, Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere 1932–3 (included in the Tate show), is a musical work. Displacing the larger of the two hanging spheres sets the smaller ball freewheeling around a set of ‘impedimenta’ on the floor around the mobile. Chance plays a role in which, if any, of these objects it might strike, causing a noise. Each release of the ball has the potential to create a singular, avant-garde musical experience.

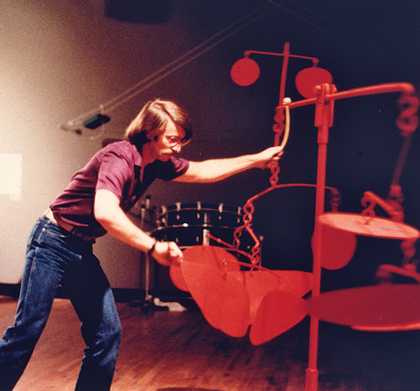

Percussionist performing Earle Brown’s Calder Piece, a sonic animation of Alexander Calder’s mobile Chef d’Orchestre 1966, at Aspen Music Festival, 9 July 1981

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York/DACS, London, courtesy the Earle Brown Music Foundation, Rye, NY, USA;

SG In relation to the performative and musical aspects of his work, was he interested in its theatrical potential and how it was documented?

AR He was well aware of its potential, beginning with the nascence of his career, with the creation of Cirque Calder, a precursor to performance-based art. An audience was always invited to his circus presentations, and attending one became a real event in artistic circles both in Europe and the United States in the late 1920s. Cirque Calder was documented twice on film, once by Jean Painlevé in 1955, and again by Carlos Vilardebo in 1961, but these don’t give a precise sense of an actual presentation.

Alexander Calder’s mobile Untitled 1936 set in motion, photographed by Herbert Matter, c1939

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York/DACS, London, courtesy Calder Foundation, New York/Art Resource, NY

SG Artists not only look forward with their work, but acknowledge looking back (and sideways) to other practitioners. As well as citing Jean Arp and Mondrian as early influences, Calder had a special relationship with Duchamp (who coined the term ‘mobile’). Very different artists in many ways, but how did they inspire each other?

AR In 1931 Fernand Léger wrote of Calder’s abstractions: ‘Looking at these new works – transparent, objective, exact – I think of Satie, Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, Brancusi, Arp – those unchallenged masters of unexpressed and silent beauty. Calder is of the same line.’ Duchamp was a powerful champion of my grandfather’s work throughout his career, one who was bewitched by his innovations. Cirque Calder inspired his Boîteen-en-valise 1935–41, and when he wrote about Calder for the Société Anonyme catalogue, he conjured Plato’s Philebus and notions of sublimation.

Installation view of the exhibition Alexander Calder: Stabilen, Mobilen at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1959

© 2015 Calder Foundation, New York/DACS, London, Alexander Calder papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

SG One art critic has said that he thought your grandfather’s work has more in common with an artist such as the Brazilian Lygia Clark and her small foldable Bichos sculptures than, say, Giacometti. What artists did he admire?

AR Actually, Lygia Clark – along with other artists such as Lygia Pape, Willys de Castro and Hélio Oiticica – were all influenced by Calder, who was a generation older than they were. He spent a considerable amount of time in Brazil, first visiting for two months in 1948, where he had highly successful shows in both Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Later, in 1953, an exhibition devoted to his work, organised by the Museum of Modern Art, was presented at the II Bienal in São Paulo. As far as which artists he admired, Katharine Kuh asked him that very question in an interview in 1962. His response: ‘Goya, Miró, Matisse, Bosch and Klee.’ But he owned more Légers than anything else.

SG What do you think Alexander Calder’s legacy is today?

AR I think his incredible innovations, along with the fortitude constantly to upend expectations of his art, are what keep his work fresh and relevant today.