Olivia Laing on Peter Doig’s Echo Lake 1998

It’s the drowned star I’m interested in. Let’s swim out to the drowned star. Saratoga Springs, July shifting into moody August. Each morning we wake to the sound of the races, the announcer chanting on a distant tannoy, the roaring surf of the crowd, hooves drumming on softened ground. Driving to the liquor store we pass the heaving gleaming glossy colts. There are five lakes on the property, each one a mirror for bending trees, green on green, the surface pocked by skimming swallows. I take my bike and cycle through the glowing woods, a gold Dodge Packard abandoned by the track, its doors thrown open, its tyres sinking into leaf mould. At night the stars come down into the pool and we climb the fence and swim together, stripping on the deck, the whiff of chlorine, cicadas drumming in the pines, the flitting summer bats. New York was what, 200 miles away; we might have been living in the 20th century, gathering in the hall to drink vermouth in highball glasses full of ice. One day we took our bikes, all of us, and plunged hell for leather down the lawn, brakes locked, wheels bouncing on the turf. I bet all my money on a horse called Lake Placid, called Summer Colony, called Tale of the Cat. It’s the pool I want to tell you about: the way the water felt. When I dived I split the stars, when I dived I made the night sky run with milk.

Peter Doig

Echo Lake (1998)

Tate

Claire-Louise Bennett on Dorothea Tanning’s Some Roses and Their Phantoms 1952

He probably doesn’t understand why I don’t contact him and make an arrangement to meet up. I’m not sure I understand why I don’t. It’s not as if I’m doing anything, I’m doing nothing in fact, really nothing. I could be with him right now. He could be here, I could have eaten my dinner with him here, instead of on my own. Wouldn’t that be nice? To arrange for him to come at seven o’clock, let’s say, for dinner? Wouldn’t that give me something to do at least, some reason to wear flattering clothes, some reason to clean the bathroom sink? He could be here, right this moment, sitting here at the table with me, and I could be talking to him – but what would I say exactly? I used to enjoy talking about my life and my ideas. I would be very serious, but not really. Rather I would create an atmosphere of seriousness in order that the man would feel I was disclosing something I’d never before divulged. I would talk as though the things I was saying were being confessed for the very first time, as if by being with him specifically something gasped inside me that produced this unprecedented way of seeing things and expressing them. And this of course would make the man feel very good about himself, he would feel he was really seducing me, and yet it’s important to confound him, to lose him; to go still, completely still. So that, for want of something better to do, his fingers search out the crushed napkin, coaxing the flaws and the phantom unwittingly from within its soft inimitable folds.

Dorothea Tanning

Some Roses and Their Phantoms (1952)

Tate

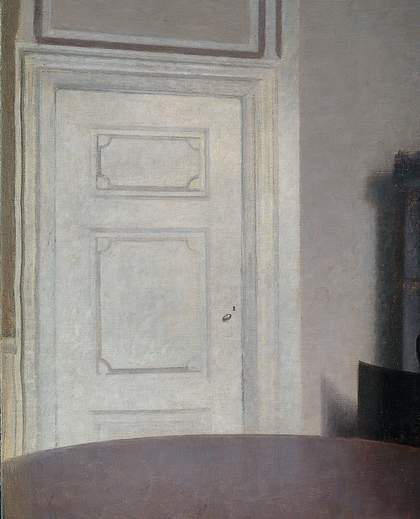

Njideka Akunyili Crosby on Vilhelm Hammershøi’s Interior 1899

Though Vilhelm Hammershøi may have intended the focus of his painting to be the woman (his wife Ida), my gaze gravitates to the exquisitely rendered doors, especially the one on the left. He deftly defines the door and its frame’s geometric topography with an economy of means, subtly shifting shades and temperatures of the colour white. Scott Noel, one of my teachers at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, said that an all-white painting was one of the hardest challenges a painter could undertake, since the artist has to come up with multiple variants of the colour that are close enough to each other still to read as white and at the same time distinct enough to separate from one another. Here, Hammershøi creates an all-white painting of the doors within the larger composition, all the while working with a limited palette.

This compounding of rectangles inside rectangles reminds me of Josef Albers’s Homage to the Square series. Since my work normally creates what Homi Bhabha calls ‘third spaces’ between disparate times, cultures, visual languages, etc, I was excited to make a couple of paintings inspired by this connection between Hammershøi and Albers. In those two works I borrow Hammershøi’s doors, but paint them in pumped-up colours as a nod to Albers. However, the doors in my pieces open on to other doors to build on the aforementioned idea of nested rectangles that expand the space in the painting by creating wormholes to other compositions.

Vilhelm Hammershoi

Interior (1899)

Tate

Timothy Morton on Samuel Palmer’s A Hilly Scene c.1826–8

I’ve loved this painting since I was eight. Palmer was part of William Blake’s crew in Shoreham, Kent, and he strangely does to Shoreham a little bit what Chagall did for his Russian village. Look at that upside-down fat slice of a crescent moon. It’s playful and charged with some kind of delight. Look at the steepness of that sugar-loaf-style hill. It’s not English, but it is… but it isn’t. That church, so tiny, yet people seem to fit inside, as if it’s the TARDIS. The perspective is extreme, as if we’re being crammed into a tiny space – the whole of that dell is maybe a TARDIS.

Palmer’s sensitivity to how things always contain much, much more inside them is what gives the painting its richness and its visionary quality. It’s fantastically compact, and those branches give it a very strong frame. We’re not looking at blurry stuff here – this is all about Blake and his ‘wiry bounding line’. Things are very specific and unique, well defined like objects in a stained glass window. Yet they are TARDISes that are so much bigger on the inside. This principle doesn’t apply just to people, as in the Romantic language of the sublime, in which we (humans) contain infinities that transcend the universe. Everything does that! This TARDIS quality is really cheap – a pencil can have it – yet for that very reason the whole world is pulsating with mystery, teeming with possibility. Shoreham isn’t just Shoreham.