Thomas Gainsborough, Wooded Landscape with a Peasant Resting c.1747, oil paint on canvas, 62.5 × 78.1 cm

Courtesy Tate Photography

Harris family holidays were not adventurous. For a week in September, we would go to the south Devon coast and look at it. We looked at the sea, the red cliffs, the still water of the estuary. Every so often I campaigned for a variation on the looking, or went off to Exeter to hang about near the shops. But I was always back in time for the ‘evening drive’, a short outing to take in a different view and see it in the low, late light.

So I became a collector of early autumn evenings. In the ancient analogy between the seasons and the stages of human life, the time of youth is spring. But I remember only one or two spring days from my childhood – it is all autumn: the orange of a few late crocosmia flowers meets the spotted, yellow fringes of the hawthorn leaves; blue skies deepen above glowing stone walls, and then it all softens to yellowy grey, a haze, a sense of distance. I felt I had to save up autumns to last the whole year, to be spread out, sipped sparingly from memory.

'Autumn views, I know now, are complicated things'

It didn’t cross my mind that past generations of 12 year olds would have worked at the wheat harvest, and here I was hoarding views instead. Nor did I wonder why these views moved me, their beauty being so obvious as to require no interrogation. But autumn views, I know now, are complicated things. Though it is logical to find pleasure in the sight of a ripe cornfield or a laden apple tree, yellowing leaves are another matter: there is nothing inevitable in our admiration of vegetation in decay.

These questions provoked particular interest in the 18th century when autumn landscapes became the focus of new enthusiasm. In the past, poets and painters had focused on autumn as harvest time. The established iconography was of wheat sheaves, apple baskets, acorns knocked from the oak trees to fatten pigs, and (most celebrated of all in French and Italian painting) plump bunches of grapes with all the promise of Bacchic delights to come. But this was not what interested Richard Wilson when he painted the ruins in his Strada Nomentana c.1765–70, perhaps remembering the light as he had seen it – or wanted to see it – on the ancient stone, still pools and rocky outcrops outside Rome.

Richard Wilson, Strada Nomentana c.1765–70, oil paint on canvas, 57.1 x 76.2 cm

Courtesy Tate Photography

There is no certain declaration of the season. But the sunlight is so low and tawny it can belong only to autumn. The lateness of the light (in the day and the year) becomes part of Wilson’s meditation on historical belatedness. All is held at a controlled distance, more one of time than of place. We see the ruins through a veil, as if smoke had accrued in the picture’s varnish and softened the lines. If we are looking back through centuries, then time has treated these buildings gently, rounding the stones, welcoming nature into cracks in the mortar.

Autumn became famous in the mid-1700s as ‘the painter’s season’. Young men on the Grand Tour timed their travels so as to arrive in Rome, and make their excursion to the temples at Tivoli, when the light was most golden in October. Then, with luck, they might see the Temple of the Sibyl as it appeared in the paintings of Claude Lorrain. Like Claude, they could look straight into the sunset, now a clement, rather than blinding, light. These were the conditions best suited to the relics of antiquity. Back in England, September scenery in Essex, Devon and North Wales commanded new appreciation. The young Gainsborough had no desire to paint Suffolk as a version of Rome, but as he sat in London remembering the places of his childhood, he thought of the woods turning from yellow to copper to dun.

When he wrote at length on the workings of the ‘picturesque’ in the 1790s, Uvedale Price considered why autumn was the season best suited to the painting of landscapes. It was, as he pointed out, a strange preference: ‘There is something so very delightful in the real charms of spring ... that it seems a perversion of our natural feelings when we prefer to all its blooming hopes the first forebodings of the approach of winter.’ He concluded that the aesthetic appeal must lie in the ‘variety of rich, glowing tints’ in the dying leaves – as opposed to the uniform greenery of spring – and, simultaneously, the quality of light, which unifies this variety in a harmonious whole.

Looking over the Herefordshire country he loved, Price saw air and paint interfused: ‘The rich hues of the ripened fruits and of the changing foliage, are rendered still richer by the warm haze, which, on a fine day in that season, spreads the last varnish over every part of the picture.’ This enquiry was couched in terms of colour and form, but Price knew that ‘glowing tints’ mattered for their associations. To paint a turning wood was not only to enjoy a variety of hues but to explore the visual language of melancholy. In the ‘scheme of fours’, which has shaped responses to the changing year since at least the time of Hippocrates, the four seasons are correlated with the bodily humours – blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm. After the sanguine spring when blood rises like sap, and the choleric summer when tempers flare, and before phlegmatic winter settles heavily over body and land, comes the melancholy autumn.

William Holman Hunt, Our English Coasts, 1852 ('Strayed Sheep') 1852, oil paint on canvas, 43.2 x 58.4 cm

Courtesy Tate Photography

Harvest and melancholy are partners at odds with each other. Harvest is a time of communal hard work followed by festivity, plumpness, plenty. The melancholic, meanwhile, turns away from the working party to wander alone, or sets down the wine glass, lost in thought. The sense of imminent tipping from one mood to the other can give the most peaceful autumn view – whether painted or seen from a footpath – a vertiginous quality. ‘Libra weighs in equal scales the year’, wrote James Thomson in ‘Autumn’, the third part of his epic poem of 1730 The Seasons, but this equinoctial poise is always just about to overbalance. When the year is pictured as a dial, as on an astronomical clock, midsummer is at the top, correlating with midday and with the middle of life. All movement after this is downward: the nights draw in with increasing rapidity towards the equinox, so that September and early October are characterised both by fine balance and by the year’s most rapid change.

Poise and falling, fruition and melancholia: Thomson’s ‘Autumn’ was supremely influential in drawing attention to these mixed moods and movements of the season. It was Thomson’s poem, as much as Claude’s Italian views, that recommended autumn as the painter’s season and sent walkers out among the hedgerows. No one before had admired the turning leaves so explicitly, or made it so clear that autumn’s melancholy might also be its pleasure. Thomson beckons us on to ‘see the fading many-colour’d woods, / Shade deepening over shade’, and on again through the ‘leaf-strown walks’ to the ‘russet mead’ and the ‘sadden’d grove’. In the gardens at Stowe, he sees the ‘last smiles / Of Autumn beaming o’er the yellow woods’. Almost a century later, in Jane Austen’s novel Persuasion, Anne Elliot walks through an autumn landscape defined for her by Thomson. Leaving love and courtship to others, she takes her solitary pleasure from ‘the view of the last smiles of the year upon the tawny leaves, and withered hedges’. She is a mature heroine by Austen’s standards, past 30, and we understand the accord between this calm, wise, undemanding woman and the season she most loves.

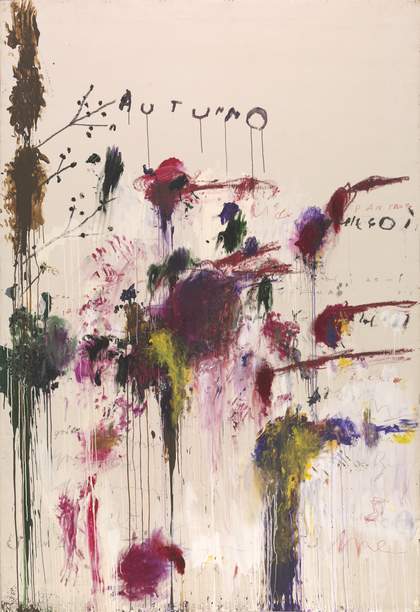

Painters whose ages match the season have taken autumn in both hands and squeezed it out, as Cy Twombly did in Autunno, the most extravagant of the four panels that make up the Tate version of his Quattro Stagioni 1993–5. It is as if he has taken possession of the magnificent black grapes from Poussin’s Autumn (The Spies with the Grapes of the Promised Land) 1660–4 in the Louvre, those fruits on the brink of bursting, carried out from the Promised Land on a pole that keeps them from touching the ground. Twombly has seized those grapes and pressed them into his white canvas so hard that the juice that flows out is both wine and blood. Here there is none of the ‘varnish’ Price so valued. Poussin’s Autumn was already breaking out from classicised serenity, and Twombly tramples out the vintage with furious power. He instructed that Autunno should be hung as the first of his season series, ousting spring and proclaiming the energy and eroticism of midlife as the genesis of all the rest.

John Everett Millais, Mariana 1851, oil paint on mahogany, 59.7 x 49.5 cm

Courtesy Tate Photography

Cy Twombly, Quattro Stagioni: Autunno 1993–5, acrylic paint, oil paint, crayon and graphite on canvas, 313.6 x 215 cm

© Cy Twomby Foundation, courtesy Tate Photography

Youthful autumns are of a different tenor. Thomson was 29 when he wrote in praise of the ‘descending year’. Gainsborough painted the turning woods in his early 20s. Holman Hunt spent six months of his 25th year at work on Our English Coasts 1852, the painting which defines, for me, the fall from summer into autumn. Week after week on the cliffs above Hastings, he rendered the raking light of an August or September afternoon, the brambles yellowing at the edges, the shadows long and sharp on the bright turf. Millais, at 22, imagined Mariana of the moated grange (that young woman trapped in an eternal autumn) stretching with the ache of ennui as the first chestnut leaves drift through the window into her room.

Tate owns a mesmerising picture by the contemporary artist George Shaw. From a series called Scenes from the Passion 2002, it is titled Late. It shows a row of garages remembered from Shaw’s childhood in the Tile Hill estate in Coventry, disused and graffitied. There’s a tree in the distance, which shines an ethereal golden yellow. In the foreground, leaves have gathered in straggling piles, blown up against the garage doors. There is a memory of Hunt and Millais in the vivid rendering of each leaf, the saturated colours, the combination of long-studied observation and momentary precariousness, as if it is all about to disappear. Shaw’s title is purposely overstated. These are paintings of the places he loved as a teenager, and teenagers feel things passionately. One senses in Late not only the nostalgia of an adult painter revisiting a childhood home, but also the more fulsome nostalgia of the child who sees each view as if for the last time, not yet trusting that the light will fall this way again. It is always ‘late’ in Shaw’s paintings of his childhood places, and that is not surprising: of the four ages of man, the first can feel the most autumnal of all.

George Shaw, Scenes from the Passion: Late 2002, enamel paint on board, 91.7 x 121.5 cm

© George Shaw, courtesy Tate Photography

Holman Hunt's Our English Coasts is on display at Tate Britain. Millais's Mariana is included in the exhibition Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphelites, The National Gallery, 2 October – 2 April 2018.

Alexandra Harris is the author of Weatherland: Writers and Artists under English skies and Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and Imagination from Virginia Woolf to John Piper. She is currently writing a book about calendars.