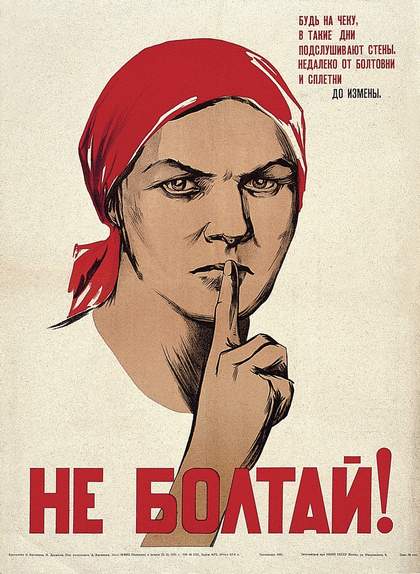

Photograph from a Stalin-era album showing the destruction of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Moscow's Miusskaya Square in the 1930s, with a handwritten caption: ‘East wall. The structure of a fence guarding against the scattering of stones during the blast.’

Courtesy Tate Photography

At the beginning of the 1980s, my interest in architecture in general, and in the architecture of destruction in particular, was rooted in my interest in space and the possibility of expressing it both in two and three dimensions. For me, architectural forms were just marks denoting the space of an endless depression, of a dead communist and socialist reality in the Brezhnev era – the greyness, dirt, coldness and endless despondency of an overall unchanging existence. This reality demanded a black and white, or rather grey, understanding of the world. The black-and-white photographs from the album of the destruction of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Miusskaya Square mesmerised me, giving me endless material for interpretation.

History stays silent on the subject of how, and for what purpose, this large, heavy album, with an embossed Lenin on its black calico binder, found its way to me, but most likely it happened around the year 1982. It is a frame-by-frame album with inscriptions right on the photographs, capturing socialist will in action: empowered workers, architects and, of course, the Soviet special services agents who supervised this event. This very album had belonged to the bureaucratic machine of socialism that had ground up both people and their creations, and it made a significant impression on me. Time had thrown out this material evidence no longer deemed useful, and, for me, it became an emotional testimony of an epoch. I peered at the faces of these lean, anxious people and imagined my own grandfather, who had been shot, and my own grandmother and mother moving with fear through a country covered by an iron curtain, and who, at any moment, might have been crushed by this huge bureaucratic machine of repression and fear. I did not use those faces in my works of that time, however, but rather what the photographs reflected – the endless destruction of cultural space.

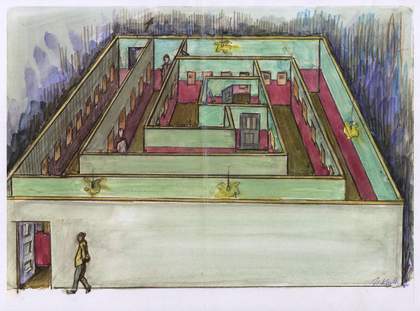

Irina Nakhova in her studio during the de-installation of Room No. 2 1984

© Irina Nakhova, courtesy Tate Photography

It’s remarkable how a single material document of one period can generate multiple documents of another. My move toward the spatial conception of my Room environments was not without the help of this album. Whole series of works were based on viewing, getting to know and emotionally experiencing this artefact – Triptych 1983, Wall No. 1 1985 and Wall No. 2 1986, as well as the polyptych Tower 1988 and diptych Simultaneous Contrast 1989. In them, I continue to discover new details directly extracted from the album and then reflected in the paintings.

Irina Nakhova's album and Room No. 2 1984 were both purchased with funds provided by the Russia and Eastern Europe Aquisitions Committee in 2017; Simultaneous Contrast 1989 was purchased with funds provided by the Acquisitions Fund for Russian Art, supported by the V-A-C Foundation in 2017.

Irinia Nakhova (born 1955, Moscow) is an artist living and working in Moscow and New Jersey. Translation from the Russian by Dina Akhmadeeva.