Still from Jack Clayton's 1961 film The Innocents

Moviestore collection Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

‘Is it haunted?’ Four years ago when I was moving from London to a medieval house in the country, that was the question I was most often asked. It wasn’t the garden or village that captured people’s imaginations, but the undoubted presence of ghosts in my house. How could they not have accumulated over the centuries on the crooked staircase and in the shadowy corners? These days, when we visit historic houses we confidently expect to hear of them, and are frankly disappointed if no stories are forthcoming – although they nearly always are.

I was intrigued to find the idea of the dead returning to their old homes so entrenched in the British imagination, and it made me reflect on the place ghosts have in our culture. We tend now to think of ghosts as personifications of our history. Was it always this way, I wondered – or have our perceptions of them changed over time? What I quickly discovered was that spirits were not always regarded as the insubstantial presences we think of today. Far from it. While nowadays a ghost might be expected to materialise, drift gently towards the door and disappear, in the 12th century it was more likely to break it down and beat you to death with the broken planks. Before the Reformation, some ghosts were thought to be refugees from Purgatory, slipping back – often in the guise of dogs or horses – to beg for prayers to shorten their suffering. Later, in the 17th century, they were devils pretending to be human spirits to trick us. Woodcut illustrations for popular ballads fixed a stock ‘ghost look’: shrouds tied up at the head, but undone at the feet – they had, of course, to walk. It was not until the late 18th century that ghosts would become transparent.

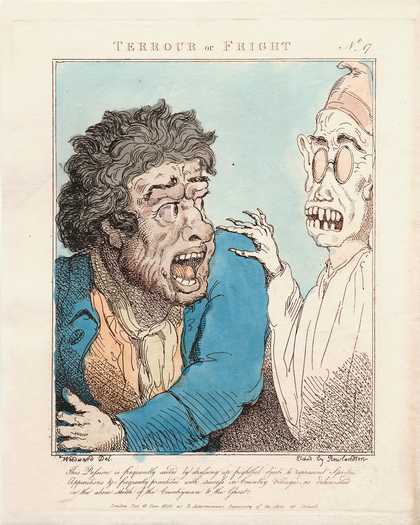

Thomas Rowlandson (after G.M. Woodward), Terrour or Fright 1800, hand-coloured etching, 27.2 x 22.2 cm

The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, CT

In order to understand more about these shifts, I looked through the eyes of artists and writers. For Pre-Raphaelites Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais, ghosts offered ways of exploring intense, psychologically charged situations, bringing an additional dimension to the dark, human dramas of their drawings and paintings. Naturally, I found plenty of them in sensational gothic novels; ever since 1764, when Horace Walpole described an armoured figure in a portrait heaving a sigh, stepping from the canvas and trudging off down a dim corridor of the Castle of Otranto, they have populated vaults and ruins and inspired illustrators. But I discovered them in unexpected places too. I was surprised by their ubiquity in James Gillray’s political satires, where ghosts can frequently be found pricking the consciences of politicians and royalty. Then I came across a group of Elizabethan pamphleteers elaborating on a literary joke in which authors sent dispatches from beyond the grave – ‘News out of Purgatory’. One pamphlet even had a frontispiece depicting its putative author, Robert Greene (who had died several years previously), sitting at his desk and earnestly writing, his shroud neatly tied up at the top of his head.

The Madonna Master (attrib.), The Three Living and the Three Dead c.1310, from the De Lisle Psalter

© British Library Board / Bridgeman Images

Some of the most arresting but less-known stories and images I found were conjured up in the medieval imagination. A richly decorated psalter created around 1310, now in the British Library, contains an illustration of a fable known as the ‘Three Living and the Three Dead’, in which a party of kings out for a day’s hunting are confronted by three walking corpses. These gruesome ghosts give the kings a warning, insisting that they, too, were once living men: ‘I was well fair’, says the first; ‘Such shall you be’, warns the second, while the third exhorts the kings, ‘For God’s love, beware by me’. The Three Dead are physically repulsive, worms writhing in their bellies and scraps of tattered shroud clinging to their bones. They were meant to be: their job was to shock readers out of their sinful ways by reminding them that they also would one day die.

And the present? Many of today’s writers and artists, from Will Self to Sarah Waters and Susan Hiller to Susan Philipsz, have tapped into ghosts’ dramatic and emotional power, giving them new forms and purposes. These are lively days for ghosts. We cannot say how they will look or behave in the future, but there can be little doubt that they will remain by our sides – having adapted, as they always do, to their new circumstances.

Adam Fuss, from the series My Ghost 2001, gelatin silver print photogram mounted on muslin, 197.5 x 136.5 cm

Courtesy the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, CA

The Ghost: A Cultural History is published by Tate Publishing.

Susan Owens is an art historian and curator and was formerly Curator of Paintings at the Victoria and Albert Museum. She lives in Suffolk.