Mark Gertler

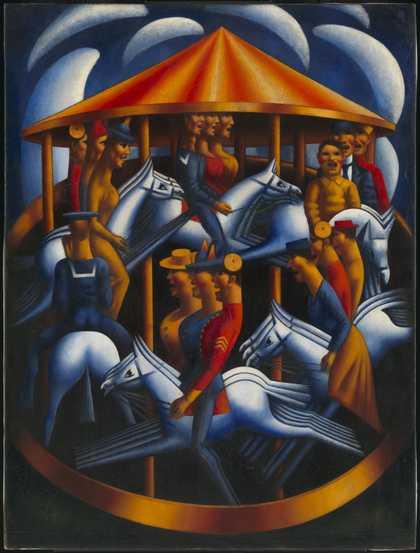

Merry-Go-Round (1916)

Tate

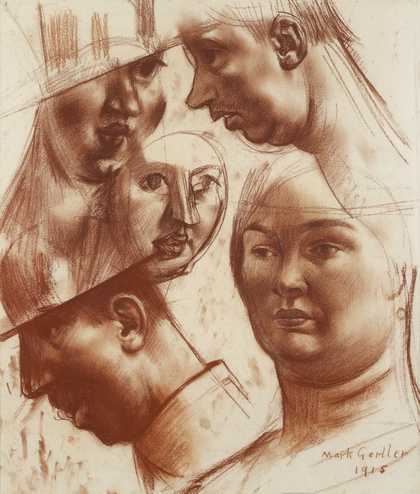

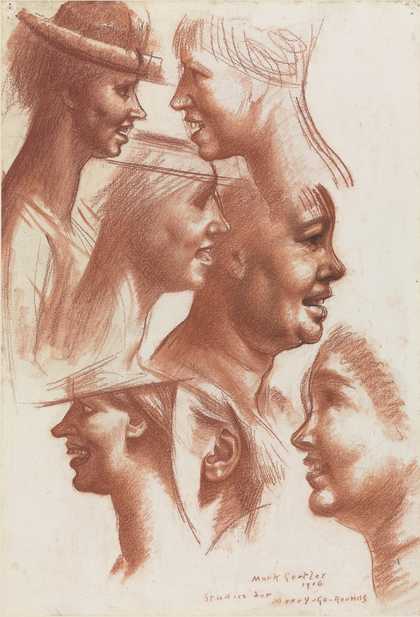

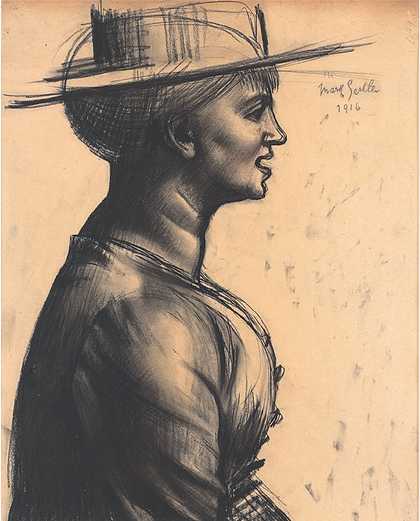

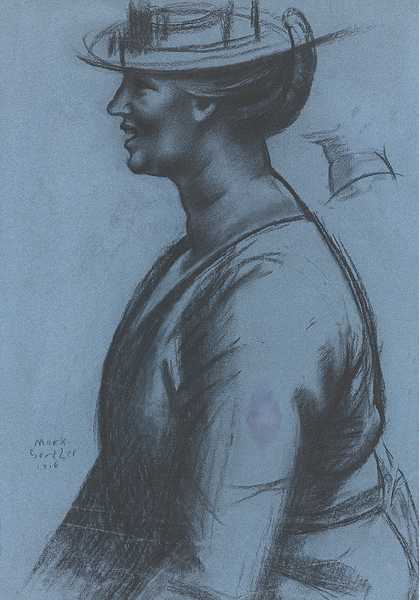

A chance visit to the annual Easter Fair on Hampstead Heath in April 1915 inspired Mark Gertler with ‘wonderful ideas’ for paintings. ‘Multitudes of people. Bright feathers, swinging in and out of the clouds in coloured boats’, and ‘a Blaze of whirling colour’ he observed. He completed a painting, Swing Boats 1915 (now lost), by August, and, the same year, also finished a study in pencil and red chalk for Merry-Go-Round, depicting two male and three female heads. The drawing was sold that November for £5 to John Drinkwater, a member of the circle of poets known as the Georgians that was centred on the art patron Eddie Marsh. There are three further related studies from 1916: a pair of charcoal drawings of women in profile, and a sanguine of six open-mouthed female heads that moves closer towards caricature.

Mark Gertler, Study of Heads for Merry-Go-Round 1915, graphite and crayon on paper, 46.5 x 40 cm

Private collection. Photo © Matthew Hollow Photography

Mark Gertler, Studies for Merry-Go-Rounds 1916, crayon on paper, 75 x 59 cm

Private collection, courtesy Piano Nobile, Robert Travers (Works of Art) Ltd

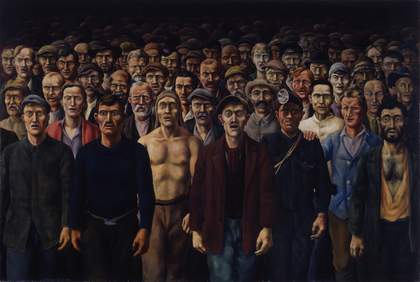

The painting was executed against the backdrop of the First World War in a climate of mounting hysteria. Following the introduction of the Military Service Act in February 1916, Gertler, an instinctive pacifist, presented himself ‘trembling in every limb’ at his local recruiting office, only to be refused on account of his Austrian parentage. ‘What luck!’ he told fellow artist Dorothy Brett, ‘Now I am free to go on with my work.’ From then until July, he was absorbed in his ‘large and very unsaleable picture of Merry-go-Rounds [sic]’, refusing to show it to anyone, including Vanessa Bell who called at his studio in March.

At Ottoline and Philip Morrell’s Garsington Manor near Oxford, he mixed with the ‘notoriously pacifist’ circle that included Bertrand Russell and the writers Gilbert Cannan, Lytton Strachey and DH Lawrence, and gave up a subsidy from Marsh, citing differences over the war. Almost penniless, he occasionally painted smaller ‘more saleable’ works, but admitted in May 1916 to fellow artist Richard Carline (then serving with the Middlesex Regiment), that ‘my heart is in my “Merry-Go-Rounds”.’

Mark Gertler, The Straw Hat: Study for Merry-Go-Round 1916, charcoal on paper, 52.1 x 34.3 cm

Private collection, courtesy Piano Nobile, Robert Travers (Works of Art) Ltd

Mark Gertler, The Straw Hat (II): Study for Merry-Go-Round 1916, charcoal on paper, 58.5 x 40.5 cm

Private collection, courtesy Piano Nobile, Robert Travers (Works of Art) Ltd

Although Gertler extensively reused canvases in this period, in this case not only did he use a fresh canvas but X-rays also reveal that he made only minor changes as he worked. Its reverse, however, he covered in multiple, multicoloured brushstrokes while experimenting with colours. A little-known preparatory study for Merry-Go-Round has recently been uncovered by X-ray beneath a Garsington landscape. It shows an earlier version of the carousel, its fuller canopy topped by a flag, and rudimentary horses galloping round then base, their criss-crossed legs forming a rhythmic pattern. In the final painting the flag is omitted, the canopy reduced, and the horses – now much larger – are fully realised: joined nose to tail, they plunge forward, forelegs raised like ‘a cluster of cavalrymen’s lances’, their hind legs kicking out like rifle butts and their teeth bared. The jaunty feathers on the women’s hats resemble the horses’ battle-alert, pricked-up ears.

Mark Gertler, The Pond, Garsington 1916, oil paint on board, 32 x 42 cm

Private collection, courtesy Piano Nobile, Robert Travers (Works of Art) Ltd

X-ray showing a preparatory study for Gertler's painting Merry-Go-Round beneath The Pond, Garsington

Private collection, courtesy Piano Nobile, Robert Travers (Works of Art) Ltd. X-ray photo courtesy Professor Aviva Burnstock, Head of Conservation, Courtauld Institute of Art

The soldiers’ distinctive, brassbuttoned scarlet tunics, suggestive of a more traditional military costume, are largely invented, perhaps based on toy soldiers; their round ‘drummer-boy’ hats reinforce the carousel’s circular motion. The inclusion of sailors may have been prompted by news of the Battle of Jutland, the largest naval battle of the Great War, which took place from 31 May to 1 June 1916. ‘Lately’, he wrote, ‘the whole horror of the War has come freshly upon me.’ As Gertler put the finishing touches to the painting, he must have been aware of the full horror of the Battle of the Somme: his riders whirl endlessly, unable to stop or get off, their mouths open in an unending scream. The stylised clouds rain down around them like bombs or Zeppelins, bursting in the sky ‘like streak[s] of light … shots bursting all round’.

The mechanistic imagery shows an awareness of futurism and vorticism, possibly influenced by CRW Nevinson’s military paintings shown at the London Group in spring 1915 and 1916, while the strong palette of orange, yellow, red and blue contributes to the painting’s violent energy. Although the composition is anchored by a series of strong verticals, the carousel’s vertiginous tilt suggests a world teetering on its axis. The painting surely also encapsulates Gertler’s despair at his unhappy affair with (Dora) Carrington, who would shortly leave him for the homosexual writer Lytton Strachey. Ironically, it was Strachey who, after viewing the canvas in Gertler’s studio in July, famously likened its effect to that of ‘shellshock. I admired it, of course, but as for liking it, one might as well think of liking a machine gun.’

The painting is undoubtedly Gertler’s outstanding contribution to British modernism, as DH Lawrence recognised when writing to him in October: ‘It is the best modern picture I have seen: I think it is great, and true.’

Sarah MacDougall is Head of Collections and joint Senior Curator at Ben Uri Gallery and Museum. She is the author of a biography (2002) and a forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Mark Gertler (Yale University Press), and co-curator of the Mark Gertler display at Tate Britain, which features both Merry-Go-Round and its studies.