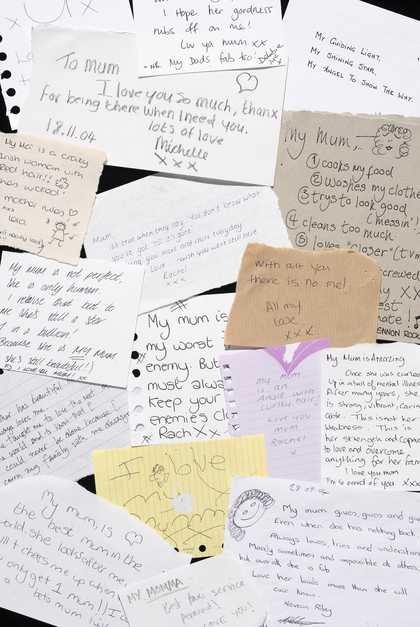

Messages left by visitors to Yoko Ono's My Mummy Was Beautiful at Tate Liverpool, 2004

Photo © Tate / David Lambert

I had never been to an archive before. The items I’d called up were in soft cardboard boxes. It was library quiet. I was allowed a pencil and some paper. There were people at some of the other tables but it was very peaceful. I opened each box separately and went through the contents. There was, right from the start, a sense of awe, almost overwhelming.

In 2004 at Tate Liverpool, the artist Yoko Ono covered the ceiling of the gallery in images of a female breast and a female pubis baring the caption ‘My Mummy Was Beautiful’. The city was covered in banners with the same images. The reception from people living in the city was less than positive.

Ono dedicated the exhibition to John Lennon’s mother, Julia, who was killed in a car crash when Lennon was 17. Lennon’s mother had been a shadowy figure in his life, rising up and then receding, often absent. She inhabits some of his songs and she, clearly, inhabited a place for Ono, despite the two never having met.

Ono did not speak of her own mother in relation to the exhibition except to write that she once was beautiful, and in the use of the past tense moves us to a place of grief; John Lennon’s mother is dead, as is he. In the exhibition a small sign read: ‘My Mummy Was Beautiful. Tate Liverpool Participation Wall. Share your memory of your mum with us.’

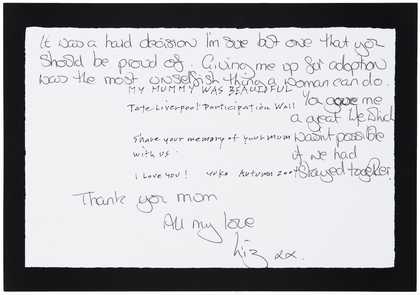

Message left by a visitor to Yoko Ono's My Mummy Was Beautiful at Tate Liverpool, 2004

Photo © Tate / David Lambert

In the archive there were boxes and boxes of slips of paper, each covered in the words people had written about their mothers. I felt that if I touched them roughly they would fall apart beneath my fingers. I moved them carefully in and out of the boxes. It seemed to me, reading them, that people had written things on these slips that they never would have said out loud. There was power in putting something down on paper and then giving it over to strangers. I felt as if I was holding a thread that ran out of the archive and back in time to all these people writing their messages. One of the pieces of paper from the exhibition had been embossed with braille words that I could not read. Another said:

It was a hard decision I’m sure but one that you should be proud of. Giving me up for adoption was the most unselfish thing a woman can do. You gave me a great life which wasn’t possible if we had stayed together. Thank you mum. All my love Liz. xx

Most of the notes were filled with love and thanks, but some were angry or anguished, disbelieving. One of my favourites of the notes reads:

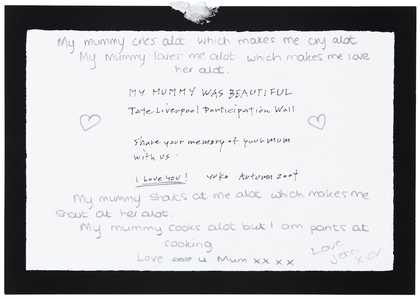

My mummy cries a lot which makes me cry a lot. My mummy loves me a lot which makes me love her a lot. My mummy shouts at me a lot which makes me shout at her a lot. My mummy cooks a lot but I am pants at cooking. Love u Mum. xx xx

Message left by a visitor to Yoko Ono's My Mummy Was Beautiful at Tate Liverpool, 2004

Photo © Tate / David Lambert

When we were young our mother used to say: only boring people are bored. She has wild hair like me and speaks her mind. There is a photo on my wall of my parents with me when I am about one. They look like teenagers.

For the next few months I am living in my campervan while I teach at York University. Speaking to my mother on the phone, she said that she found it strange because she could not even envisage me in the way she normally could when we spoke. I realised that I knew what she meant; that I could still see her standing at the kitchen counter, eating Battenberg cake and drinking almost-cold tea.

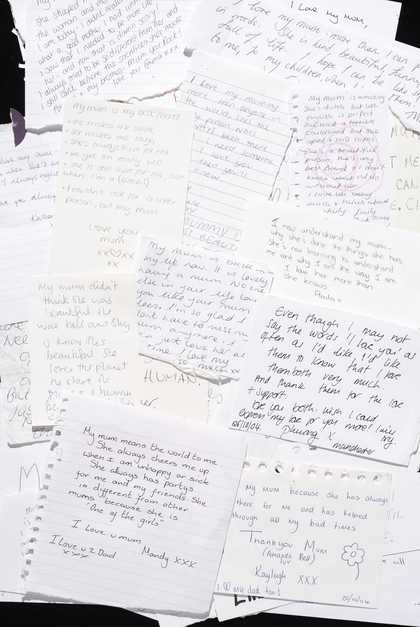

When I was a child we lived for a short time in a tall house whose top floor looked out towards Ely Cathedral. One morning I stood on a chair and threw notes that I’d written out of the window. Later my parents made me go out and pick them up from the gardens where they’d fallen. I cannot remember what I was writing or who I was writing to, only the feeling of jubilation; the spire of the cathedral breaking up into the blue sky. I do not know if there is a sense of this in my writing now, of reaching out, of throwing something up towards an unwatchful sky. It is frightening to think too much of this, of what it means to put something down on paper, to press it into the world in that way. I do not think any of those writing their notes could have imagined me, 14 years later, sat at a table in the archive, reading the things they had written. Perhaps they had supposed no one would look at them.

One of Margaret Atwood’s rules for writing is to bring two pencils onto a plane in case the first one breaks. And I want to say: bring nothing, write nothing down.

Messages left by visitors to Yoko Ono's My Mummy Was Beautiful at Tate Liverpool, 2004Messages left by visitors to Yoko Ono's My Mummy Was Beautiful at Tate Liverpool, 2004

Photo © Tate / David Lambert

Yoko Ono’s My Mummy Was Beautiful was commissioned by Liverpool Biennial 2004. The response cards collected from visitors to the exhibition at Tate Liverpool are available to view by appointment in the Tate Archive. Liverpool Biennial 2018, Beautiful world, where are you? continues at venues across the city until 28 October. Double Fantasy: John & Yoko, Museum of Liverpool, until 22 April 2019.

Daisy Johnson is a writer living in Oxford, by the river. Her debut, Fen, was published in 2016. Her novel, Everything Under, is published by Jonathan Cape.