Editor's Note

‘Was ist das, girl? the teacher asked the student who was sitting on the floor using a makeshift backstrap loom. The teacher was Josef Albers, then the influential head of design at the Yale School of Art, and the student was Sheila Hicks, who had taken up weaving to learn more about pre-Incaic textiles. This encounter took place in the mid-1950s – a time when weaving was still a relatively marginalised discipline. Perhaps recognising a kindred spirit, Albers went on to tell Hicks that his wife Anni was also ‘interested in this kind of thing’ and introduced them, as Hicks recounts.

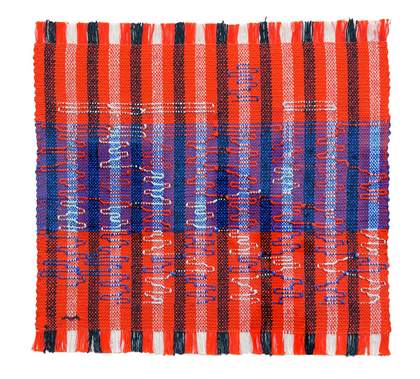

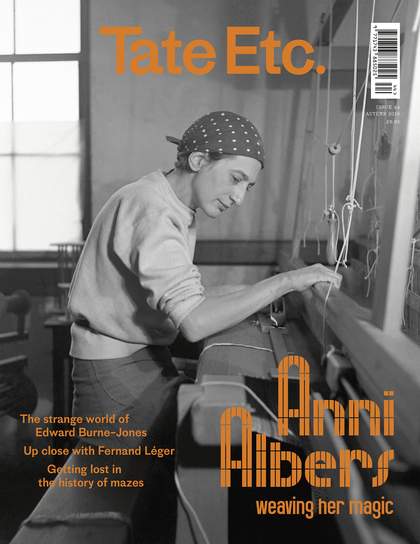

By this time Anni Albers already had several decades of experience to her name, having been a key force in her field (along with Gunta Stölzl) during her stint in the Bauhaus, as well as being the first designer to stage a one-person exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1949. However, it is only now that Albers is finally receiving global recognition for being the pioneering artist that she was, as the forthcoming retrospective at Tate Modern will reveal. Not only a consummate teacher of her discipline, she also revitalised the ancient craft, creating beautiful works of art to rival any of those made by her painterly contemporaries.

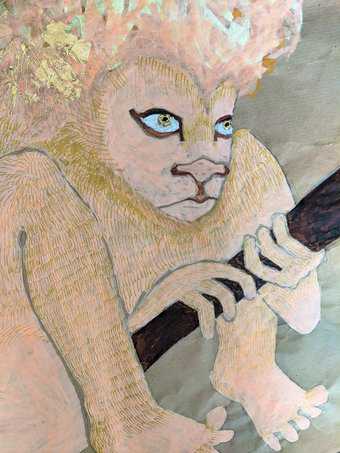

The work of the late-Victorian artist Edward Burne-Jones may seem a world away from that of Anni Albers, yet one imagines that his wish to democratise the arts would have found favour with her. Like Albers, he defied the traditional methods taught in art schools of the day and, as the curator of Tate Britain's exhibition writes, ‘developed his own idiosyncratic practice by disregarding the intrinsic properties of a medium and following his own instincts.’ From the loose brushwork to the compositions conjured by his strange imagination, this impulse is what makes his art seem so fresh today. It might also explain why his legacy endures in the work of contemporary artists such as Elizabeth Peyton, just as Albers’s rigorous attitude to art and life continues to speak to new generations.