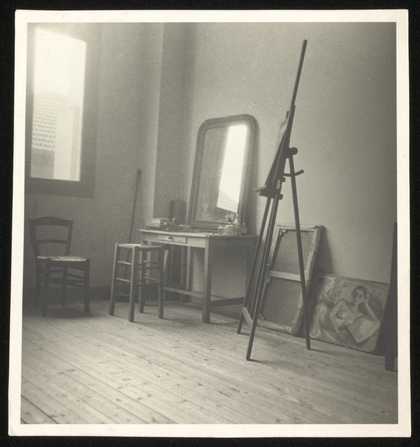

Unknown Photographer

Photograph of Marie-Louise’s studio in Paris, showing her painting ‘Model, Vienna’ on the floor behind the easel ([c.1930])

Tate Archive

When I was a child, I loved going to the Dean Gallery in Edinburgh to see the mocked-up studio of Eduardo Paolozzi. I stood in silence and gazed at the arms half-liberated from stone, the heads and legs and buckets of plaster, picturing it as Dr Frankenstein’s laboratory. Since then, I have sought out the workplaces of artists: Ernest Hemingway’s in Havana, with its 10-foot writing desk and hunting trophies; Frida Kahlo’s in Mexico City, with the mirror above her bed which she used to paint self-portraits; Henrik Ibsen’s in Oslo, with the painting of his enemy and rival August Strindberg hanging above his desk to motivate him. Back home I have visited the studios of friends, and while they have dropped pencils and moved shelves, I have been afraid to touch anything, treating the rooms like still lifes.

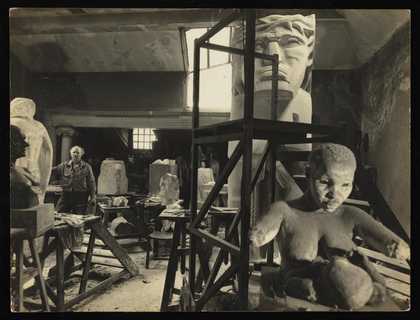

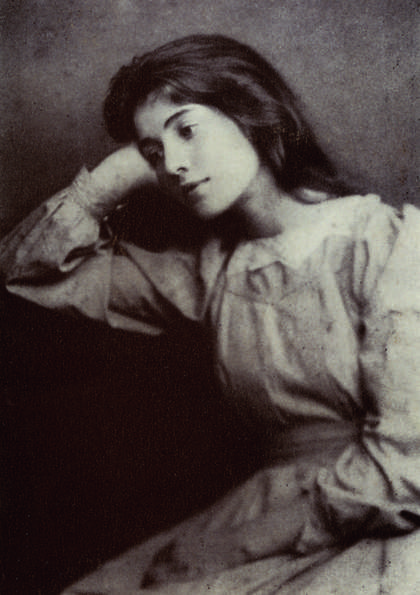

The Tate Archive reading room feels hushed and reverential when I visit on a damp day in early February. I am addressed in whispers, handed cardboard archive boxes. I am here to see collections of photographs of the painter Marie-Louise Von Motesiczky and her studio, and of the sculptor Jacob Epstein. The pictures spill on to the desk, some as small as postage stamps. There are personal photographs in the folder – Epstein with Frisky (‘a very friendly and sensitive little animal’), and Von Motesiczky smiling on skiing holidays. And yet, the photographs of the studios seem the most personal of all. There are chips of stone on the floor, dusty ladders, paint-speckled easels – little glimpses into how both artists work, like eavesdropping.

As I look at these photographs (‘Late 1930s?’ scrawled on the back of one), I think of how an artwork is static like a photograph, and how the creation usually outlives the creator. Motesiczky’s easel is empty, her studio neat, a finished artwork tucked against the wall. But Epstein’s studio is haphazard, in contrast to the pristine finished pieces. His sculptures are in various stages of completion, some mere fragments, hulks of stone that still have the potential to be perfect. His work, at this point, is as fluid and changeable as he is. It can grow into anything.

I am always struck by the notion that an artist’s environment is alchemical, forming and inspiring their work. At events I hear questions about the writing process: how, when, where do you write? As if, by buying a seaside cottage and using a quill and vellum, we too might be able to write Middlemarch. If, the myth goes, these rituals and working environments are reproduced, so too can the essence of that artist be distilled and captured. A studio becomes charged with magic.

My father and my husband and I built my studio in the winter of 2015. I wore a respirator as I wadded out the walls with fibreglass, my husband developing a maniacal fondness for the nail gun. The tulips were out by the time we topped out, sunbathing on the felt roof and opening a bottle of prosecco. I felt on the verge of something, the heady sense that here I would be able to form beautiful things. Here was my own studio.

As with me, the studio is crucial to the characters of my novel. The Doll Factory is about freedom and art and curiosity and obsession. Silas, a curiosity collector, works in the quiet cellar of his shop, dressing mice in miniature outfits. Louis, my fictional Pre-Raphaelite artist, has an eccentric studio crammed with marble hands and peacock feathers and blown eggs. Iris, my protagonist, moves from painting in secret in the cellar of a doll-making shop, to finally being given her own attic studio. This is the moment where she unfurls as an artist.

Sitting at my own desk, I am thinking about my second novel. It is tender and raw and I want to protect it, like my pots when they are newly thrown. I could glaze them in any way, smooth out each fingernail mark. As with Epstein’s half-hewn sculptures, my novel has the potential to be perfect (though it will not be) or to go awry. Sadly, I have no mortal enemies whose portraits I can hang above my desk or nearby moors to roam for inspiration. Ultimately, I try to remind myself that my imagination matters, not the environment I am in.

A selection of Marie-Louise Von Motesiczky archival material will be on display in the Archive Gallery, Tate Britain from 7 October.

Elizabeth Macneal is a potter and author based in east London. Her debut novel The Doll Factory is published by Picador.