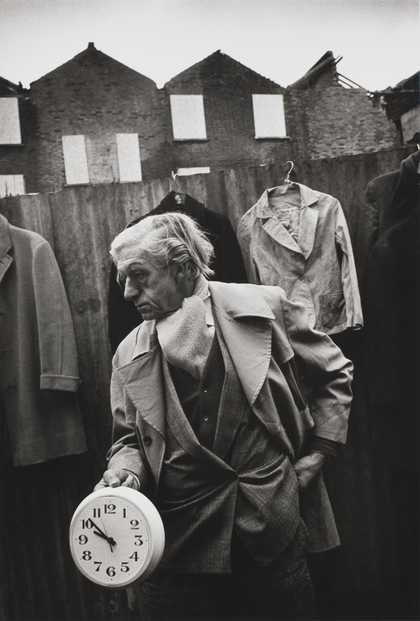

Edith Tudor-Hart, Edith Tudor-Hart [self-portrait] c.1936

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Presented by Wolfgang Suschitzky 2004

‘My sister had a hard life. That is for sure’, says Wolfgang Suschitzky near the end of Tracking Edith, my recent documentary film on his sister’s legacy. Every family has its secrets. I had always known that my Austrian-born great-aunt was a highly talented, professional documentary photographer. But it was not until 20 years after her death in 1973 that I learned she had led a double life.

As a secret agent helping the Soviet Union for decades, Edith may have influenced the course of history: she introduced a young British student, Kim Philby, whom she had met in Vienna in 1933, to her communist handler Arnold Deutsch, who then recruited him. Philby went on to become the most notorious member of the Cambridge Five.

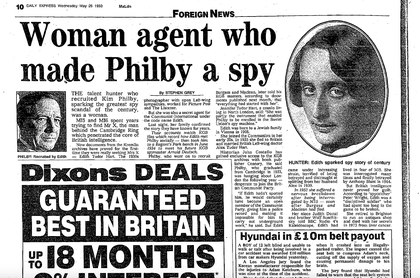

Daily Express, Wednesday 26 May 1993, p.10

A year and a half after the break-up of the Soviet Union, an article in the London Daily Express identified Edith as ‘the 1930s photographer with open Left-wing sympathies’ and as one of the most important ‘talent hunters’ who had ever worked for the KGB. A photo of Edith from the 1930s, never before seen, was captioned ‘HUNTER: Edith sparked spy story of century’. The image showed large eyes and an uncommonly intense gaze.

The article surprised and fascinated me; nobody in my family could tell me anything about it. ‘Wolf’ Suschitzky dismissed the story as a prank. My mother, Edith’s cousin, considered it a lie typical of the British tabloids.

Edith Suschitzky was born in Vienna in 1908. Her parents owned a bookshop in a working-class district, as well as a small publishing house that printed progressive books. Her father, a dedicated socialist, was an early influence, but his politics were never extreme enough for Edith.

At a young age she joined the Austrian communist youth movement. Aged 16, she had already left her parents’ house to take up a course with Maria Montessori in London, intending to be a kindergarten teacher. She later went on to study photography at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany using a Rolleiflex camera throughout her career to deliver her strong social message. She saw the camera as a political weapon – one that could help bring a wider awareness of the working-class life she saw in Vienna, London and the Rhondda Valley in Wales: shocking living conditions, unemployment, disease and hunger.

Edith Tudor-Hart, Unemployed Workers’ Demonstration, Vienna 1932

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Presented by Wolfgang Suschitzky 2004

Edith Tudor-Hart, Unemployed Workers’ Demonstration, Trealaw, South Wales 1935

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Presented by Wolfgang Suschitzky 2004

In 1933, Edith was jailed for a month in Vienna after acting as a courier for the Communist Party. That same year she married a British medical doctor, Alexander Tudor-Hart, who had left his wife and two children to be with her. They settled in England, where Edith spent the rest of her life.

She worked for several British magazines – The Listener, Picture Post and Lilliput among others – and earned a very modest income as a children’s portraitist. She was never paid for her work as an agent, suffering tremendous financial hardships throughout her life.

Curator and photographic historian Duncan Forbes deserves credit for helping establish Tudor-Hart as an important photographer 40 years after her death. In 2013, Forbes curated two exhibitions of her work at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh, and at Vienna’s Wien Museum. Nevertheless, her magnificent body of work remains far too little known.

Following Kim Philby’s first arrest in 1952, Edith burned many of her negatives in order to protect herself after enduring repeated interrogations by MI5 agents and having her apartment searched several times. She was even referred to as ‘the grandmother of us all’ during a 1964 confession by Cambridge Five member Anthony Blunt, but MI5 were unable to provide evidence of her espionage.

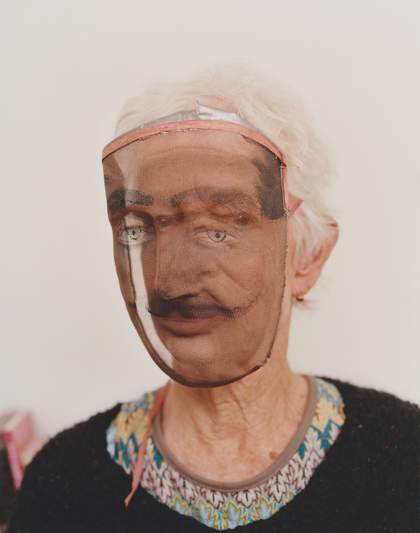

Edith Tudor-Hart, Untitled [self-portrait with unknown man] c.1935

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Presented by Wolfgang Suschitzky 2004

Eventually forced to abandon photography, she resettled in Brighton, opening a tiny antique shop there on Bond Street. She lived right above the shop and it was in that small apartment that I saw her for the very last time, perhaps one or two years before she died. As far as I can remember, Edith came across as someone rather sad the few times I met her, perhaps partly due to the fact that her son Tommy, born in 1936, was severely autistic, even considered schizophrenic at the time. He was placed in mental institutions from the age of 11, never to be fully released.

Edith remained a staunch communist until the end of her life. I have often asked myself why. Her passionate belief was intransigently linked to her conviction that communism would meet the need for more social justice, that it would prevent the rise of fascism, that a strong Soviet Union would be a major force against these threatening developments.

Wolf Suschitzky’s first-born son Peter, Edith’s nephew, believes that helping Russia in its struggle against Germany had been her main goal – before the war at least. But why, I insisted, cling to it to the last? ‘Well, actually stopping her work for the secret services of the Soviet Union would have been hard to do, as once you are in, you can’t leave’, Peter Suschitzky replies. ‘They would have threatened her with betrayal to MI5.’

But perhaps admitting that she had made a mistake, in the light of history now known, would have also meant the realisation that she had chosen a terribly wrong path for her life. Although some people managed to make that admission, many could not. Would Edith have been able to take better care of her son if she had been working only as a photographer? Would she have been able to develop her talents to a far wider extent? We will never know.

Edith Tudor-Hart, Basque Refugee Children Preparing Vegetables, North Stoneham Camp, Hampshire, 1937

National Galleries of Scotland. Presented by Wolfgang Suschitzky 2004

A display of photographs by Edith Tudor-Hart and Wolfgang Suschitzky, curated by Kate Bush, Adjunct Photography Curator, opens at Tate Britain on 27 May.

Peter Stephan Jungk is a Paris-based writer and filmmaker, and director of the 2017 documentary film Tracking Edith.