Unknown Photographer

Photograph of Marie-Louise von Motesiczky wearing a fluffy hat and an overcoat ([c.1980s –1996])

Tate Archive

‘Passionate, devoted, frank, tender, shy, single-minded and self-critical’ are how friends described the extraordinary artist Marie-Louise von Motesiczky (1906–1996).

Born into a rapidly vanishing world of the rich and cultured Jewish haute bourgeoisie in Vienna, Motesiczky grew up in a happy household where artists, philosophers, composers and writers were regular visitors.

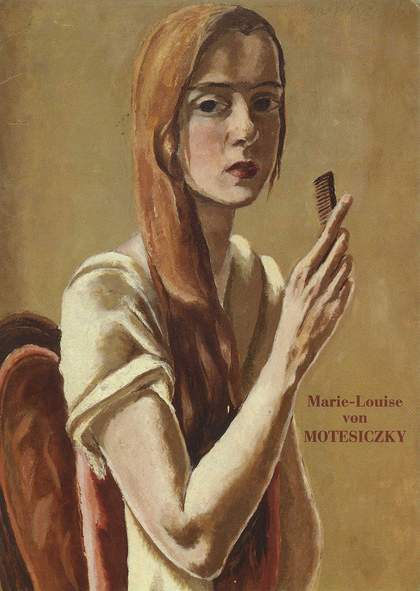

By the age of 13, she had the clarity and confidence to decide to become an artist and left home to take art classes on what would be a quasi-grand tour around Europe, taking in studies in The Hague, Vienna, Paris and Berlin. Whilst in Paris, she painted Self-portrait with Comb 1926, an incredibly assured work that demonstrated that she was a real talent. It also revealed the influence of Max Beckmann, who the Motesiczky family had known since 1920 and whom she would see while in Paris. By the end of 1927, Beckmann had invited her to his influential classes at the Städelschule in Frankfurt, after which she spent the following decade in Paris and Berlin developing her still lifes and insightful portraits.

In March 1938, her life was to take a dramatic turn when the National Socialists marched into Austria to annex the German-speaking nation for the Third Reich. The following day Motesiczky and her mother Henriette fled to the Netherlands with only the few personal possessions they could carry.

Cover of the catalogue for the exhibition Marie-Louise von Motesiczky at the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna, February–April 1994, featuring Self-portrait with Comb 1926

Courtesy Tate Library and Archive

After a brief stay in Amsterdam, where Motesiczky managed to get her first solo exhibition, they left for England. ‘One can only imagine what would have happened to us if we had taken a different route’, she later said. Her brother Karl had stayed in Austria and joined the resistance, only to later be betrayed and sent to Auschwitz, where he died in 1943. Mother and daughter would spend their war years in Amersham, on the outskirts of London, during which time, Motesiczky joined the Artists’ International Association and took part in their exhibitions. She renewed her friendship with Oskar Kokoschka, and also got to know the writer Elias Canetti, who would be her lover, supporter, promoter and friend for the following 30 years. As well as sitting for several pictures, Canetti greatly admired her art: ‘You are a very great painter and, whether you want it or not, the world will come to know it.’

After the war Motesiczky moved to London and in the ensuing years the world did get to know her art, through solo exhibitions in increasingly prestigious venues: the Städtische Galerie, Munich (1954), Beaux Arts Gallery, London (1960) and at the Vienna Secession (1966) – an exhibition that then toured to Linz, Bremen and Munich. Despite this, her adopted country’s reception of her work remained muted.

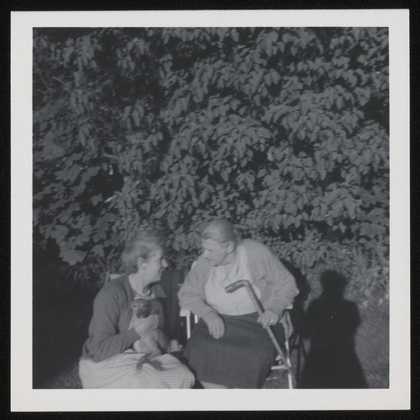

In the early 1960s she finally settled in Hampstead, this time joined by her mother Henriette. Here she befriended many in the vibrant European émigré community, which included the painters Milein Cosman and Charlotte Bondy, as well as the art historians Ernst Gombrich and JP Hodin.

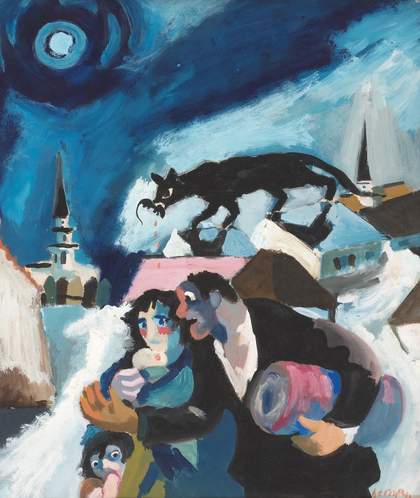

Marie-Louise Von Motesiczky

From Night into Day (1975)

Tate

Motesiczky’s most successful works reflected her defining relationships, and in her mother she had found the perfect subject. Henriette, whom she cared for full-time, would become one of her constant and favourite models. While their relationship was close, it was not straightforward. In an interview late in life, Motesiczky felt that she had ‘sacrificed’ herself for her mother: ‘My mother would be happiest if I had laid in a basket by her bed.’ That said, her art did not suffer, and the portraits of Henriette turned out to be some of the most psychologically intense and moving depictions of an ageing body.

In works such as From Night into Day 1975, painted in her exuberant expressionist style (in part indebted to Kokoschka), we see Henriette sitting up on one elbow in her bed. Her bald head is exposed and she bears a lucid, defiant look on her face, looked on by her pet whippet. ‘She was my favourite model ... the portraits of my mother kept me alive,’ Motesiczky said. ‘I found something uniquely beautiful about her.’ In this late series of paintings Gombrich would recognise her skill in bringing to life a moral pathos that he would compare to Dürer’s charcoal drawings of his mother. Motesiczky would paint her mother until Henriette’s death, aged 96, in 1978.

Unknown Photographer

Photograph of Henriette and Marie-Louise von Motesiczky with a dog on her lap, sitting down in a garden ([c.1960s])

Tate Archive

Despite the consistent quality of her art, it was not until 1985 that she received proper acclaim in England after a retrospective at the Goethe-Institut. Critics praised her as a ‘dazzling’ talent. Following this success, three of her works, including From Night into Day, entered the Tate Collection. In 1994, just two years before she died, her solo exhibition at the Belvedere in her home city of Vienna confirmed her status as an important Austrian painter of the 20th century. Despite the affirmation, Motesiczky was reluctant to part with any of her works and preferred to keep them in close proximity around her house, reminding her of the exceptional life she had led.

The Archive Gallery at Tate Britain has been renamed in perpetuity as the Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Archive Gallery, in recognition of the largest gift from the Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Charitable Trust to the archive, where there is a display of items exploring her life and work until 22 March.

Simon Grant is Editor of Tate Etc.