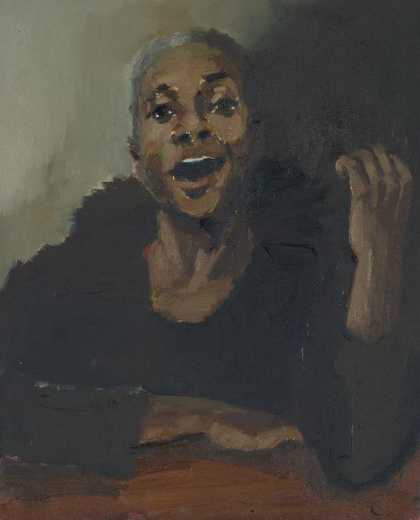

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

First 2003

Oil paint on canvas

Laurie Fitch. © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, courtesy the artist, Corvi-Mora, London and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

ANTWAUN SARGENT When there’s a show like this – your first major survey – which starts at the beginning of your career with a painting called First 2003, it exposes your journey as an artist. What has the process been like in terms of reflecting on your practice?

LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE Well, it’s weird, because there are specific points where I can see that I went to certain extremes and then pulled back again – purely in the way that I was thinking about the work and the way that I was painting. In my head, that began with the painting First, from my final-year postgraduate show at the Royal Academy Schools. It marked the start of where my work has been going ever since. Prior to that, the work was quite different.

AS Different in what way?

LY-B It was in a different format – there was much less ambiguity in a way. I would say that the composition was more complicated, with more narrative; it was more about trying to push certain ideas into a painting, to illustrate them. I wasn’t thinking about painting in the same way that I had for my degree show, when I finally took on board what everyone had been saying to me for many years: ‘If you’re going to paint, you actually need to think about painting.’ It’s not about having an idea that you then try and translate into paint. You have to speak through painting.

AS Did they mean thinking about painting physically, or the history of painting?

LY-B The physicality. I think it was my most visceral show to date. From there, I had a few years where I was thrashing it out. There was a certain appreciation for vulgarity, a certain kind of madness that was as much to do with having found something new as not knowing what to do with it. And it was about beginning to understand what you’re about in a strange way. I think that then switched to something far more pared-back stylistically, something more economical about mark making.

AS Where did that lead you?

LY-B The paintings then went to the other extreme where things were very, very simplified – sanitised somehow. I wasn’t entirely happy with that either, so I pulled back. There was a point around 2008 where a lot of things changed in my life. A few things happened that scared me to death, basically, and introduced another mentality altogether. I felt: ‘I can either second- guess everything and worry about what the world thinks, or I can just do what makes sense to me.’ Since then, I’ve felt a lot calmer – maybe because you realise there’s nothing to do but to do it. And that spurred me on to get a bit closer to my own true passions. Looking at it now, I see that. I’m seeing all these points in time.

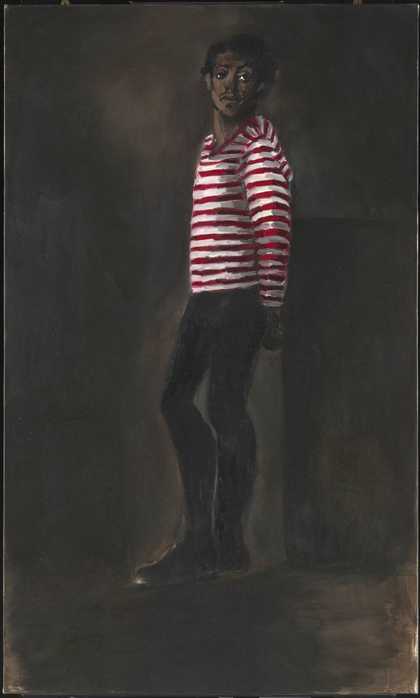

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Wrist Action 2010

Oil paint on canvas

Private collection. © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, courtesy the artist, Corvi-Mora and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

AS One of the things that has changed over the last 15 years is how quickly you paint. You famously used to make one painting a day, which is something that you’ve kind of moved away from. How has your thinking about the creation of a total painting changed over the course of your career, and how do you see that in this particular survey?

LY-B For me it was always a matter of practicality, the business of completing a painting in a day. It was never a performance or an attempt to find a hook or an edge; it was just the way I had to do it in order for the painting to not be a complete failure, because the conditions in the studio had always dictated as such. It was quite warm, things would dry partially overnight on canvas, and then I couldn’t go back and work over them without creating a muddy, scratchy, crappy surface. I just wasn’t sophisticated enough as a painter to do it any other way, so it became this thing that I had to do. The only way I could resolve something was if I finished it in one day.

AS Did you change your studio practice or techniques to allow yourself more time?

LY-B Over time, I’ve found ways of perhaps spreading things over a few days. But I still need the urgency. I’m too impatient to spend months and months on anything – it’s not how I work. Something that helped was learning how to work on linen properly and that actually allowed me to able to revisit things. The work shows that there’s another type of history you can build into your painting – another type of progression, another kind of temporality.

AS That’s interesting, because the way that I was introduced to your work was first on canvas, then on linen, so I’m thinking that it was a shift that happened later, but experimentation with linen was a part of your process from the beginning?

LY-B Yes, it was always so hit and miss for me, because I didn’t fully understand how to make colour work on linen at that time, so everything that was on linen was very monochromatic. There wasn’t that range of colour, which was partially a confidence thing as well. Linen is unbending – it has a tooth, you have to kind of fight with it. It doesn’t give the way that a smooth canvas does.

AS Does that change the texture of the figure in any way?

LY-B Yes, it does. There’s a different type of nuance in my head now. Early on, I got to thinking a lot about the physicality of actually painting and how I feel working on canvas: the rhythm it takes on, and how that affects the rhythm in the figure and the rhythm in the depiction of faces. With canvas, there’s a kind of smoothness, a romantic flourish. It comes from a fluid gesture, whereas on coarse linen, the way that you have to build a face, the way that you build limbs, there’s a different, much coarser and unbending depth to that romance.

AS Who are some of your early influences? I know Prince is someone that you point to musically, which, in my mind, you can see when you talk about painting with a sense of rhythm.

LY-B Yes, I always think of my painting influences as really going hand in hand with musical influences. That has to do with what I listened to in my formative years – that’s why Prince always comes up. But then, when I started to listen to jazz, it marked my thinking about rhythm. Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Bill Evans. Passages in sound that move unexpectedly. Or the tones in the voice of Nick Drake. At a very particular point during art school I listened to him every day. Studying by the sea at Falmouth College of Arts for three years also affected my thinking and philosophy.

AS When you consider jazz as an influence, is it about improvising? Does that translate to going where the brush takes you?

LY-B Yes, there’s always an element of improvisation. Still, I need anchors, I need a plan of sorts. There’s always something that I think I want to do, but, more and more, I’m learning that I can’t always dwell on trying to make a thing work, because often it’s a waste of time. It’s better to allow something to just go somewhere else. There’s a recent painting, Repose IV 2019 of a man lying down with his hands behind his head, which was a completely different painting initially.

AS In what way?

LY-B Well, it was a man lying back, but there was another figure in it and they were outdoors. It didn’t work. I’ve learned that, rather than spending days or hours agonising over the fact that something doesn’t work, and trying to make it into the thing that you wanted it to be, sometimes it’s better just to let it be something else. Then, try that other thing next time. I’ve always revisited certain themes, and that is normally to do with feeling that I hadn’t got everything I wanted the first time round. It’s also another form of anchoring: you revisit something or someone in order to anchor yourself to a body of work, to remind yourself of a bunch of reference points, or ideas or thoughts or feelings.

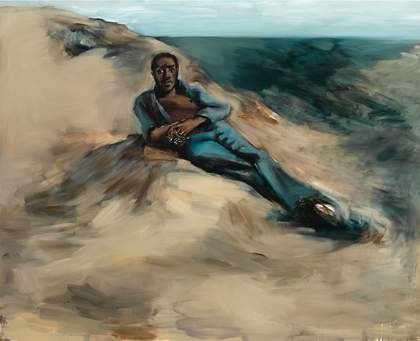

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

6pm Cadiz 2012

Oil paint on canvas

Danjuma Collection. © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, courtesy the artist, Corvi-Mora, London and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

AS Thinking about reference points, anchors, influences and inspiration, there’s also a literary current in the construction of the way that you’re thinking about your figures and in the titling of the work. I know you write fiction and poetry. How does being a writer affect the building of a painting?

LY-B Hand in hand with music and painting as influences, I also think certain writers have been important. People like James Baldwin, Ted Hughes, Marlon James, Zora Neale Hurston. There were certain references from literature that stuck with me, and made me think differently about language in relation to imagery. So the titles have never been descriptive; they’re never explanations of the paintings – they’re always another brush mark, a part of the painting, rather than a description of it.

AS There’s also something very psychological about the titling of the work. It may not be a roadmap or explanation, but I find it helps to create mood and provide narrative.

LY-B Yes, definitely. At the same time, in my own mind, the way that I catalogue things is according to these titles. It could be something that I associate with a particular word or phrase, or the look in someone’s eye in the painting that sparks something in me – that makes me think of this word or phrase.

AS Much has been said about the ways in which you paint a figure: the idea that they are kind of abstractions borne out of your relationship to the world, but mostly out of your imagination. The paintings are not portraits of real people. You anchor representation in the imaginative, which, to me, suggests a future or dream. How did you move away from, say, a real-life figure to propose a different type of figuring of the black body?

LY-B I trained working from life, and painting from life and drawing from life – and that was necessary to get the tools – but I think I learned early on that the psychological charge or the emotional charge that comes from doing that wasn’t something that I particularly liked to work with, because I had no control over it. I realised that in trying to paint my friends, trying to paint these incredible people I knew, that I wasn’t capturing them. I was capturing something else, maybe, but not really them. It was a different discipline in that sense, and I realised my interests lay more with the painting, and also with stepping a couple of degrees away from reality.

AS So how do you work to compose a scene or figure?

LY-B I work from scrapbooks, I work from images I collect, I work from life a little bit, I seek out the imagery I need. I take photos. All of that is then composed on the canvas. So, from doing that, a few things came about. One of these was the possibility to really think through the painting, to allow these to be paintings in the most physical sense, and build a language that didn’t feel as if I was trying to take something out of life and translate it into painting, but that actually allowed the paint to do the talking. The other thing that came out of that process was this idea of the infinite possibility of blackness, of black life. There were these ideas about how a black body should be, should move, what blackness means. I can divorce the work from that expectation of reality and refer to a different reality. My figures are recognisably people. One of the things people assume about my stance is that I don’t want to talk about race and that somehow this isn’t political. It’s never been that. I just don’t like being told who I am, how I should speak, what to do and how to do it. I’ve never needed telling. And so this idea of infinity, this idea of the infinite, of the impossible, of anything being possible, that’s what I think about most, that is the direction I’ve always wanted to move in. Following my own nose and doing as I damned well please has always seemed to me to be the most radical thing I could do. It isn’t so much about placing anyone in the canon as it is about saying that we’ve always been here, we’ve always existed, self-sufficient, pre- and post-discovery, and in no way defined by who sees us.

AS There’s a certain level of rootedness in your images that is about a kind of pride in the human condition. It stands in contrast to what is expected of the black figure and black artist, which is a protest – that is to say, a justification of their presence in art. In your work, there’s a real universalness to the figure, meaning, as Toni Morrison once said, they are the centre, they are the mainstream. They are not interested in the marginalising of themselves.

LY-B Exactly. I’m not the ‘other’ in my life at all. If we think in those terms, the ‘other’ for me would be white, surely? The point I’m always making at the moment is that there’s never this freedom to be everything in between. You’re a goddess or a slave. Most of us are neither. It’s never been about an accepted notion of protest, nor the accepted notion of celebration. There is so much else to think about.

AS So the work is not about an idealisation of the figure of the body, which, in some ways, allows for some sort of relief, right?

LY-B I hope so. I feel like it is.

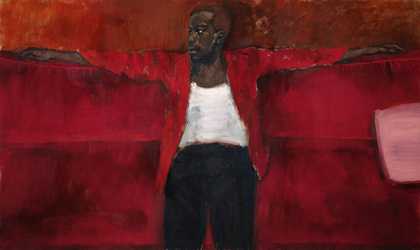

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

To Improvise a Mountain 2018

Oil paint on linen

© Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, courtesy the artist, Corvi-Mora, London and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

AS I feel like the representation of the painted black figure in the history of art, or more contemporarily, is rooted in an obsession with idealising life in a way that takes the truth out of it, takes the messiness out of it. One of the things that I’m drawn to in your work is the way that the mark making disavows perfection and archetypes, which is a different type of situating the figure in a landscape, in our imaginations, and a history of painting.

LY-B It’s a way of encountering the infinite, just as it is in our lives – the complexity of an existence that isn’t pinned to these very specific expectations or ideas about the potential of our lives. There is magic there, good and bad.

AS I think this idea of a complex black life comes out in the way that you hang your paintings. It’s something that a lot of people, including the artist Glenn Ligon, have taken notice of. The figures are hung at eye level, and they are in communication. They’re looking at each other, exchanging glances, although they are not necessarily in the same scenes, but there’s a communal atmosphere. The move is curatorial.

LY-B I would often be really disappointed with the way that things were hung if I didn’t hang them. I came to realise that I could actually do it myself, and take steps so that it was done the right way. That comes with experience – a growth in confidence, perhaps – and people actually giving you the space, and trusting you to make those decisions. I make the work at my height, my eye level, so that’s how it should be seen. It doesn’t make sense to hang it any higher than that, because I wouldn’t see it right, which means that perhaps most people wouldn’t see it right. It has to do with height but also having a physical connection to something. I think we work with an awareness of our own scale, so hanging a work at the height that it was painted, for me, is a part of the way of bringing back that feeling. It’s also about how things work in dialogue with each other, so that the directions people are looking in, the gestures, the scale of the figure on the picture plane, those shifts and dialogues and conversations that happen between the paintings are what inform the paintings essentially. With the Tate show, the real challenge was to actually organise these rooms, keeping in mind these relationships and dialogues across years, and across bodies of work. I don’t think so much in terms of individual paintings in a show, I think about the conversation between them.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

The Ventricular 2018

Oil paint on linen

© Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, courtesy the artist, Corvi-Mora, London and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

AS It does take on the feel of an installation, because the walls are often coloured a particular way, which places the consideration of any one painting in relationship to the room, and to the looking relationships. Part of that comes from, at least in my mind, the way that you’re thinking about colour and the way that you’re using colour. Very often, to make the brown skin of a figure, there are reds and blues and greens underneath to give it a certain light or mood.

LY-B Over time I’ve got more confident, and perhaps a little bit better at working with colour, because it was always something I struggled with – and still struggle with. The real revelation, in terms of thinking about colour, was that no colour exists in a vacuum. Colour is always relative. Skin tone has to be seen in relation to its surroundings; the two are informing each other. So there is no one skin-tone black, there is no one leaf green, there is no one sky grey or sky blue. When I struggled to work with colour in painting, it was because I didn’t understand what colours do to each other. This is what the painting comes out of, from the way that my eyes perceive, the way that our eyes compensate, or make sense of colour, in order to form the thing in front of us.

AS Thinking about how looking relationships inform colour choice, and ultimately the figures themselves, brings me to how you depict men and women in your work.

LY-B My awareness that the figures are recognisably people means that I feel a certain responsibility. There are just certain things that I wouldn’t feel comfortable doing. I once did feel comfortable depicting women, or men, in certain ways, but less so now. There are certain modes of loucheness or sexiness that I’m less interested in working with.

AS I think sexiness in the work comes off as a kind of intimacy. The dancers are sometimes posed in ways that have a sexual feeling to them, but it’s translated as a kind of love, as a kind of…

LY-B Sensuality.

AS Yeah, exactly.

LY-B It’s a sensuality over sexiness. I mean, I think that the sexiness for me has always been the painting itself. The physicality. Purely in terms of the image, I’ve always felt a certain responsibility and reverence. I think it’s why I’ve always struggled with nudes. I’ve painted nudes – that’s how I trained. When I was at art school I did it frequently. It was just a very different way of working. It never sat well with me in my own renderings. This is not to denigrate anything else – I’ve just not figured out how to do it. For me, the nuance really doesn’t work when it slips from sensual into slutty – and that’s for both men and women. Those slips happen so easily and then suddenly you have a different work.

AS I don’t know if I’ve ever seen a painting of yours where there are men and women together.

LY-B There are one or two out there! It’s true, it’s something that I just haven’t really managed. The way I’ve found to make that work is to put them on separate canvases next to each other. I love the conversation that can happen, and the fact that they can be two separate things, but the same thing. The fact that they have this divide – they’re looking across an abyss of sorts – and yet they’re next to each other. As soon as you have a man next to a woman, there’s a particular narrative suggestion. I don’t especially want that. There are a couple of works that exist where there’s that narrative, and they work in a very different way, but I just didn’t want to have to negotiate that every single time.

AS The sense of time in your painting is also important. Time is like a sublime force one experiences looking at your paintings. Since this is your first major survey, what does the passage of time, from the beginning of your career to now, say about you as an artist?

LY-B The best I can hope for is that, by now, there is some clarity to my vision, that people feel perhaps a little of what I feel, what I love, and why I love it. And how that love keeps me going.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night, Tate Britain, 18 November – 9 May 2021. Curated by Andrea Schlieker, Director of Exhibitions and Displays, Tate Britain and Isabella Maidment, Curator of Contemporary British Art with Aïcha Mehrez, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art. Supported by Denise Coates Foundation, with additional support from the Lynette Yiadom-Boakye Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Organised by Tate Britain in collaboration with Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, and Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand- Duc Jean.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye is an artist and writer who lives and works in London.

Antwaun Sargent is a writer and curator living and working in New York. His recent book The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion is published by Aperture.