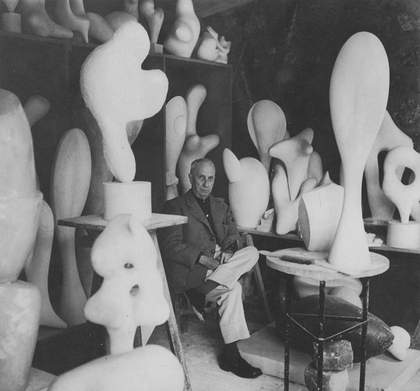

Jean (Hans) Arp surrounded by his biomorphic sculptures in his studio at Meudon, near Paris, 1958, photographed by André Villers

The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence. Artworks © DACS 2021

For a word that was to become synonymous with sensuality, the first mention of the word ‘biomorph’ in relation to art is as dry as a bone. In 1895, the British anthropologist and ethnologist Alfred Cort Haddon observed in his book Evolution in Art that: ‘the biomorph is the representation of anything living in contradistinction to the skeuomorph which … is the representation of anything’. However, despite some detours (the ‘neo-vitalist’ theories of the philosopher Henri Bergson have a role to play in this story) ‘biomorphism’ only really entered the lexicon 40 years later, in the pages of the modernist art magazine Axis. In 1935, the English curator, poet and art critic Geoffrey Grigson – one of the cofounders of London’s ICA in 1946 – used it to describe an approach to painting, sculpture or design that referenced organic life forms. In his essay ‘Comment on England’ (1935) he wrote that ‘abstractions are of two kinds, geometric … and biomorphic’. In another essay, ‘Painting and Sculpture’ (1935), he observes that: ‘“biomorphic” is no bad term for the paintings of [Joan] Miró, [Jean] Hélion, [Hans] Erni and others, to distinguish them from the modern geometric abstractions and from rigid Surrealism.’

Sarah Lucas

NUD CYCLADIC 6 (2010)

Tate

In 1936, Alfred H. Barr Jr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, referenced ‘biomorphism’ in his book Cubism and Abstract Art without mentioning Grigson’s essays, which led some to assume that Barr himself had coined the term. He observed that in the art of Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse there is a current that is ‘intuitional and emotional rather than intellectual; organic or biomorphic rather than geometrical in its forms; curvilinear rather than rectilinear, decorative rather than structural, and romantic rather than classical in its exaltation of the mystical, the spontaneous and the irrational.’

Barr also cites Joan Miró and Jean (Hans) Arp as exemplars of the biomorphic approach. More recently, in his book Biocentrism and Modernism (2017), the art historian Oliver A.I. Botar highlights the role that ‘nature-centric ideologies’ play in the development of much 20th-century art and draws a connection between developments in modernism and modern biology, in particular, in the work of Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Jackson Pollock.

Paule Vézelay

Strange Landscape (1933)

Lent from a private collection 2016

As a term, biomorphism – which derives from the Greek words bios (life) and morphe (form) – is a broad church: it’s been used to describe such disparate work as the surrealist paintings of Leonora Carrington, André Masson and Yves Tanguy; abstract works by Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, Jean Arp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Paule Vézelay; the art nouveau designs and buildings of Antoni Gaudí and Josef Hoffmann, and the industrial designs of Alvar Aalto and Isamu Noguchi; the sculptures of Louise Bourgeois, Constantin Brancusi, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Auguste Rodin; and the landscapes and nudes of the photographer Bill Brandt.

What links all of these artworks and designs – despite their often very different motivations – is the sense that their forms, even at their most abstract, are somehow alive. They curve, swell, balloon or appear to float. They also often evoke structures – such as the spiral of a snail’s shell, the amorphous shape of an amoeba or cells observed under a microscope – that are found in nature. It’s important to stress that biomorphism is visible in the work of seemingly countless contemporary artists. This should come as no surprise: after all, its source is life, which never stops.

NUD CYCLADIC 6 was purchased in 2012; Strange Landscape was lent from a private collection in 2016.

Jennifer Higgie is Editor-at-Large of Frieze magazine. Her book on historic women’s self-portraits, The Mirror and the Palette, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.